Ebola-Resistant Genes? Genetic ‘Predisposal’ To Virus May Show Promise For New Vaccines

New research into the effects of the Ebola virus on mice has shown that genetic differences played a major role in determining which animals experienced severe Ebola symptoms and which exhibited only mild signs of the infection. The experiment, the first of its kind, could indicate that genetics play a similar role in humans, according to a study published Thursday in the journal Science. If scientists can pinpoint the exact genes that allow some human Ebola patients to avoid the worst symptoms of Ebola, such as hemorrhaging, it could help speed up the development of potential vaccines against the virus.

“This [experiment] will ultimately allow us to not only better understand what predisposes an individual with a particular genetic background to either susceptibility or resistance [to Ebola], it will also provide a genetically diverse yet reproducible model in which to test drugs and vaccine,” Angela Rasmussen of the University of Washington and a lead researcher on the study, told Forbes.

Scientists identified two genes in mice that controlled for resistance to the worst symptoms of the disease. Both genes produce the proteins TIE1 and TEK, which help regulate how much fluid passes through the walls of the body’s blood vessels. These genes were less active in mice that experienced hemorrhaging -- a symptom that produces the bloody eyes, gums, vomit and diarrhea witnessed in about a third of human Ebola patients.

Scientists have known that Ebola affects people differently, yet exactly why that is isn't fully understood. “All we know is that not everyone gets hemorrhagic fever, not everyone gets sick,” Michael G. Katze of the University of Washington, who, along with Rasmussen, started experimenting with mice and Ebola three years ago, told the New York Times. “There are a million articles about Ebola but very little scientific literature on the virus.”

Some people are thought to be completely resistant to the Ebola virus. Others suffer moderate symptoms such as fever, and still others become seriously ill. Hemorrhagic symptoms occur in about 30 percent to 50 percent of patients, according to the New England Journal of Medicine. Natural resistance to the Ebola virus is critical to a patient’s likelihood of survival, researchers have said.

Researchers’ first step was to develop a strain of Ebola that would replicate in mice, as they do not contract the same Ebola virus that humans do. Once that was accomplished, the team was able to replicate the same spectrum of symptoms that is seen in humans, in mice.

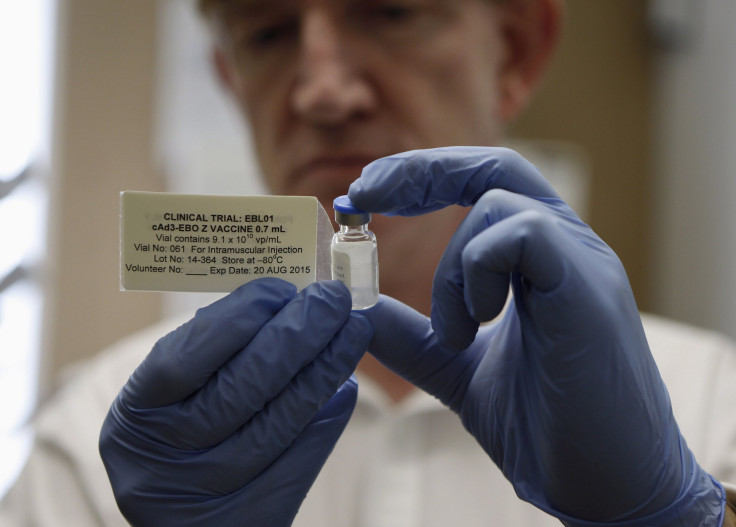

Experimental drugs against Ebola like Zmapp contain antibodies against the virus and work by boosting immunity. The virus is ultimately defeated by the body’s immune system, however buying the body more time to develop antibodies could mean the difference between life and death, researchers said. An Ebola vaccine that targets the genes that control for hemorrhaging could give patients who do not have a natural resistance to the virus a fighting chance. There have been over 13,700 confirmed or suspected cases of Ebola worldwide and nearly 5,000 deaths in the current outbreak, according to the U.N.’s latest figures.

The study is “the first step in being able to do this kind of genetic analysis in humans," Katze told the Washington Post. "You can go to the doctor and get your genome sequenced and find out how likely you are to get certain types of cancer. Maybe someday they'll also say, 'Hey, don't go to West Africa, it looks like you're susceptible to Ebola.'”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.