Iran's nuclear deal: The toughest of all challenges

- Published

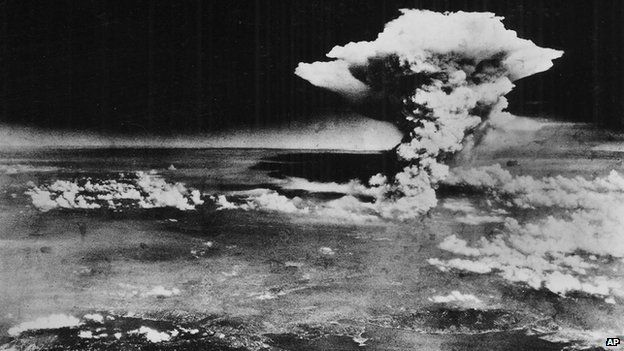

We're fast approaching the 70th anniversary next month of the dropping of the first nuclear bomb, on Hiroshima.

The world changed on 6 August 1945. Arguably, the appalling effects of that first atomic strike - and the subsequent attack on Nagasaki - have played a large part in the determination to prevent the use of far more devastating weapons developed since.

Back then, the US was the only nation with "the bomb".

The story since has been of the steady spread, the proliferation, of nuclear weapons: first to Russia, Britain, France and China - then to Israel (although never officially acknowledged), India, Pakistan, North Korea.

The big powers seemed either unable or unwilling to prevent that spread except perhaps now - in the case of Iran.

All sorts of conflicting signals are coming out of the international talks in Vienna meant to end all the hostility between the major world powers and Iran over its much disputed nuclear programme. There's talk of both breakdown and possible breakthrough.

So why is it judged so important to stop Iran?

I asked Sir John Sawers, chief British negotiator with Iran from 2003 to 2007, and after that the UK's representative on the UN Security Council when sanctions against Iran were being decided.

He said: "If Iran acquired a nuclear weapon, then it would change the dynamic across the Middle East.

"It would make them invulnerable to any response to their unacceptable behaviour in the region."

Possibilities for peace

Sir John told me: "If there is an agreement then, first of all, it gives everyone much greater assurance that Iran is not going to make a break for nuclear weapons.

"It opens the possibility of Iran and its Arab neighbours coming together and developing a more normal relationship.

"At the moment, the Middle East is riven by disputes - many of them along Sunni-Shia lines - and if we can create a possibility whereby Saudis and Iranians can talk to one another and it is not driven by continuous hostility, then there is a possibility of creating a different sort of Middle East."

It's not just August 1945 which hangs heavy over the negotiations with Iran.

The events of February 1979 in Iran itself, and everything which has followed, help explain the years of suspicion and outright hostility between Tehran and Washington which a nuclear deal could do so much to ease.

Ayatollah Khomeini's triumphant return to Tehran - on 1 February 1979 - from exile in Paris to take power as supreme leader of an Islamic Republic symbolises the moment when the US and its allies lost control of Iran with the fall of the shah.

The years of blatant Western interference were over.

Ayatollah Khomeini

Ruhollah Khomeini was born in Kohmeyn in central Iran. He became a religious scholar and in the early 1920s rose to become an 'ayatollah', a term for a leading Shia scholar.

Arrested in 1962 by the shah's security service for his outspoken opposition to the pro-Western regime of the Shah. His arrest elevated him to the status of national hero.

Exiled in 1964, living in Turkey, Iraq and then France, from where he urged his supporters to overthrow the shah.

In January 1979, the shah's government collapsed and he and his family fled into exile. On 1 February, Khomeini returned to Iran in triumph.

There was a national referendum and Khomeini won a landslide victory. He declared an Islamic republic and was appointed Iran's political and religious leader for life.

Islamic law was introduced across the country.

The new religious leadership inherited a nuclear research programme, but consistently denies expanding it with the aim of making "the bomb".

The big powers have never accepted that, pointing instead to all the Iranian effort to produce highly-enriched uranium in the quantities you could only need to build a bomb, as well as the secrecy and alleged concealment of so much activity which is specifically outlawed by the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty to which Iran is a signatory.

Years of pressure applied by sanctions and negotiations to find a way forward have now reached a point where agreement could - just could - be possible.

I spoke to Ariane Tabatabai, of Georgetown University, who, like me, has been in Vienna to follow what is supposed to be the endgame in these talks.

Time for a deal?

She told me: "Ultimately, the negotiations are about making sure that Iran's nuclear programme remains peaceful and to do that it needs to provide a set of assurances and that would mean Iran scaling back some of its nuclear activities.

"It will also provide more transparency to the International Atomic Energy Agency to make sure that everything is essentially under constant monitoring, with enhanced access given to its facilities so the international community can verify that Iran is holding its end of the bargain."

Which brings us neatly to the unanswerable question: Is the Iranian leadership ready to make a bargain?

It could be, partly to pacify those Iranians fed up with sanctions which help cripple their economy and symbolise isolation from a fast-developing world they yearn to be part of.

There are still several issues to reconcile before a nuclear deal can be reached

Professor Ali Ansari, historian of Iran at St Andrews University, pointed me to another of the country's ambitions, which is to recover some of the global respect which Iran believes it is due.

"What the Iranians are after is a degree of respect as a country that considers itself a great power - certainly in the region - that has not had a good time in the last century or so.

"The real pride and achievement is that they have developed what they've considered to be an indigenous nuclear industry.

"One of the arguments many people have made is that an Islamic government wouldn't be scientifically advanced.

"Well for the Iranians, you know, this is, sort of proof that it actually can be, if they put their mind to it."

Carpet sales tales

But Prof Ansari is far from certain that a deal can be done, and - even if it is - that it will hold.

And Sir John, from all his years negotiating with Iran, is blunt: "Whenever you buy a carpet in Iran, you have to buy it two, three times over.

"You sometimes feel that is the same in the nuclear negotiations as well. There is an Iranian saying that the real negotiation only begins once the agreement is signed.

"They will always come back for more. Even if we get an agreement - it doesn't mean it is 'peace in our time'."

So suspicion on both sides remains strong.

Whatever happens in the next few days, building and then maintaining trust between Iran and the key world powers, particularly the US, is still the toughest of all the challenges.

- Published14 July 2015

- Published1 July 2015

- Published30 March 2015

- Published14 July 2015

- Published20 January 2014