The exodus of talent from Tesco makes for extraordinary reading. So far in 2015, Britain’s biggest retailer has lost five non-executive directors and dozens of senior managers who have either been made redundant or left for better jobs elsewhere.

In any context, this would be a shock for a retailer. But in the context of Tesco battling against a slide in sales and the drama of 2014, it is even more eye-opening.

The string of departures in 2015 follows the arrival of new chief executive Dave Lewis last year and an accounting scandal that led to nine senior executives being suspended, six of whom have not returned to the company.

Replacing non-executive directors is one thing - they are supposed to be independent and new arrivals can bring vast experience to the company - but replacing senior executives is another. Tesco has lost its UK boss, head of online, the chief creative officer, commercial director, head of group planning and insight, the operations and development director, the managing director of Tesco Metro and the chief executive of new food experiences.

Many of these job titles demonstrate why Tesco got into trouble in the first place - they are a nonsense, an indictment of a company that became too bloated and was unable to react decisively to a change in shopping habits. Lewis is now trying to streamline Tesco and that is no bad thing.

However, the process of rebuilding the company is going to be a long one. No retailer can lose the talent and experience that Tesco has without disruption.

Not only that, but the morale of the remaining Tesco staff has also been impacted. Imagine working in Tesco’s head office in Cheshunt - as well as saying goodbye to colleagues and friends, the company’s cost-cutting plan means you are losing your final-salary pension scheme and you have been told you are moving to new offices in Welwyn Garden City.

Sources within Tesco say that Lewis has done a tremendous job of boosting morale and helping staff to realise that the changes he is making are vital to the company’s future. But it is understood that 250,000 staff across the UK were put into consultation and told their jobs were at risk as a result of the cost cutting plan.

These dramatic changes at Tesco show why talk of a fightback by the company and its peers is premature. Lewis clearly helped to steady the ship by growing sales during the vital Christmas period. However, this was partly achieved by Tesco offering sharp discounts on Black Friday in late November and issuing reams of £5-off vouchers for customers who spent £40. The company has warned that it will not make a profit in the UK for some time, so Lewis has effectively had a free ride to grow sales at any cost. But long-term, that is not a sustainable way to do business.

Structural change

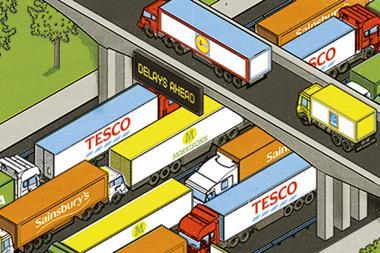

We are witnessing a structural change in the grocery industry where sales are moving from out-of-town supermarkets to discounters, convenience stores and the internet, which by their nature are a less profitable model.

This is a painful transition and the established players are being forced to reset their profit margins. Even Waitrose, which has been one of the best-performing retailers, has suffered a fall in profits. Mark Price, the boss of the upmarket grocer, warned that trading will be challenging for a decade.

One of the reasons Price fears the pressure will last that long is that retail has a habit of behaving in virtuous or vicious cycles.

So, while Tesco is struggling, Aldi and Lidl are prospering and that makes it even harder for Tesco. Like the rest of the ‘big four’, it has reined in expansion plans while Aldi and Lidl have not. Indeed this year, Aldi plans to open more shop space than Tesco, Sainsbury’s and Morrisons combined, according to new research. So even when your local Tesco store gets its act together, it might find that Aldi has opened next door.

Britain’s ‘big four’ supermarkets still account for 74% of the country’s grocery spending. In the next few months, they may maintain or even start to grow their market share again, but profits are unlikely to follow. Tesco, Asda, Sainsbury’s and Morrisons are on a long, hard comeback trail, and their staff

are feeling it.

Graham Ruddick is deputy business editor (retail and technology) at The Telegraph

No comments yet