One of the mysteries of the spectacularly successful global market for art is that the higher the value of all transactions climbs, the more instability it seems to create at its very heart, in the duopoly of auction houses that account for almost a quarter ($14 billion) of the overall art market’s estimated $60+ billion in sales.

This week Sotheby’s made three announcements—a new CEO from outside the industry, a new Chairman in the form of fashion executive Domenico de Sole and a timetable for the company’s much-touted second-take on a partnership with eBay. Together, these moves were meant to bring to a close a 20-month interregnum at Sotheby’s caused by an activist board campaign to get the auction house to return capital to its investors.

That fight unleashed hidden forces at Sotheby’s that eventually drove current CEO William Ruprecht out and brought de Sole into power. Litigation over Sotheby’s poison pill revealed that some of Ruprecht’s own board members were disappointed with him—and themselves. “The evidence is strong that [the] company has a serious set of expense and comp issues,” the former lead independent director wrote in an email. “And that the Board … is too comfortable, too chummy and not doing its job.” Those accusations, along with his huge war chest, is what enabled activist investor Dan Loeb to take control of three board seats through his hedge fund, Third Point, last May. Loeb, who also helped engineer Marissa Mayer’s accession to the Yahoo CEO slot, is said to be “psyched” with the Tad Smith hiring.

Although the agitators were seeking a simple pay day, the board fight was set against an art market seemingly in flux. Buyers’ taste has shifted aggressively toward contemporary art; art itself is increasingly being used as an asset for the world’s wealthiest; and the specter of internet retailing continues to loom over the art market even as it has made little meaningful headway in claiming market share.

To many observers, the dawn press release on Monday, March 16 about Tad Smith, a former trade magazine executive who had spent much of the last few years in local cable sales and a brief stint managing the notoriously domineering Dolan family’s Madison Square Garden, had being named as Sotheby’s transformative new CEO was a shock. To some, Smith seemed a pale copy of Christie’s recently ousted change-agent CEO, Steven Murphy. (Art trade veterans were quick to remark that Phillips had—in 2009—been the first auction house to try its hand at importing a media executive to run an auction house when it had hired Bernd Runge from Conde Nast. That appointment lasted fewer years than Murphy’s.)

During Sotheby’s pre-market conference call, de Sole made every effort to sell Smith as a seasoned executive even claiming “he does know how to manage a global sales force across different channels.” Though the last 15 years of Smith’s resume—CEO of The Madison Square Garden Company; President, Local Media at Cablevision Systems Corporation, where he was responsible for Cablevision Media Sales, News 12 Networks, and Newsday Media Group; CEO of Reed Business Information, a U.S. business-to-business division—shows no obvious place where Smith might have gotten global experience.

Murphy, whose own appointment was derided when it was initially announced, eventually came to benefit from the perception that Christie’s had done much more than its rival Sotheby’s to create an online marketplace for luxury goods and lower priced Contemporary art. (Though his predecessor has suggested in the press that the cost of running these online auctions led to Murphy’s ouster.) Which explains why Sotheby’s cannily coordinated the one-two punch of executive appointments on Monday and details of the eBay launch on Tuesday.

Everyone sitting on the sidelines assumes that the future for both auction houses lies in building an infrastructure that will unlock hidden value through scale. Even in its leaderless form, Sotheby’s trades at a whopping price-to-earnings ratio of 24 times trailing twelve month earnings. Investors clearly believe it is inevitable that Sotheby’s will figure out the internet someday.

When the Wall Street Journal asked Smith about his plans to supercharge Sotheby’s with technology, he responded by pointing “to an earlier calling card,” reporter Kelly Crow wrote. “While at Cablevision, he said he led a team that created a system that allowed the cable company to tailor the ads it broadcast to its 2.5 million households, with dog owners getting more dog-food ads and new homeowners getting additional home-improvement store ads.”

“Tad is a great strategist,” De Sole said on the conference call steering the conversation away from Smith resume and toward what hoped to telegraph as the real reason behind Smith’s having got the job. “He really understands brands and brand building.”

“The brand is already extended in three different ways,” Smith said in response to an analyst’s question, referring to the company’s three principle sources of revenue: auction sales, private sales and a small financing business. (Sotheby’s does license its name to a real estate broker, Sotheby’s International Realty, now owned by Realogy.)

Tad Smith wasn’t talking up brands because of his own business experience. Nobody loves Cablevision and the Knicks haven’t made any new friends this season. He was using a language that leads inevitably back to Domenico de Sole himself. The brilliant business mind behind the rise of Gucci and Tom Ford, de Sole fended off the acquisition interests of Bernard Arnault in 1999 by engineering an alliance with Arnault’s rival Francois Pinault. But the plan ended up backfiring, Ford and de Sole left Gucci in 2004 because of Pinault’s meddling.

Outgoing Sotheby’s CEO William Ruprecht brought de Sole onto Sotheby’s board as lead director in December of 2013 to counter the vocal attacks of the activist hedge fund group. Monday’s announcement that de Sole has assumed the title of Chairman of Sotheby’s board of directors can be read in two very different ways depending on one’s view of the state of the art auction business.

The first view is that, as lead director, de Sole selected the unseasoned Smith over his colleagues doubts. Without a strong candidate, de Sole was forced to step in as Chairman and provide Smith with the gravitas of his abundant experience in the fashion and luxury business. The alternate view is that de Sole has some unfinished business both professionally and with Pinault. In this version, de Sole is calling the shots but needs a younger, energetic public face to log the air miles, rally the troops and take the heat.

In either case, de Sole’s track record as legendary luxury brand builder would result in the constant references made in the conference call to Sotheby’s brand—and brand potential. But Sotheby’s brand is not what’s ailing the firm. To all but the most plugged in of insiders, Sotheby’s is the art auction business.

Where the brand is being tarnished to the initiated is in the world of private sales where Sotheby’s recent results showed a dramatic drop of nearly 50% after the firm lost at least two key executives. At a recent art fair one prominent art advisor fumed about the division bobbling a seven-figure sale with a new client who, according to the huffy advisor, will never deal with them again.

That’s a brand problem! But not exactly how the duo of de Sole and Smith are thinking about Sotheby’s brand. They view it like the fashion business where handling temperamental creative types, nurturing their genius and knowing how to sell it profitably is the important skill set. That was de Sole’s inimitable talent. He grew Gucci by using the firm’s distribution network—and Tom Ford’s sex appeal as a designer—to attract other world-class talent to him so he could manage them equally well and profitably. Sotheby’s is already trying to do that with RM Auctions, the classic car auctioneer it just took a stake in.

From Smith’s comments, however, he and de Sole seem to be thinking of something else. It’s true that a fashion powerhouse like Gucci was born out of saddle maker who transitioned into snaffle-bit loafers in a textbook brand extension that eventually led to Tom Ford’s fashion dominance. But there were no successful Gucci phones or Gucci cars.

The worlds of fashion and art have been intermingling for almost a decade now. But the auction house doesn’t have much control over what it can bring to the podium. If it sells one artist well, it cannot—like a fashion company—put in an order for five times as many next season or offer the same thing in new colors. Sotheby’s is a great luxury brand but it doesn’t make anything but sales.

Sotheby’s defines its brand—as Christie’s does—around its ability to market goods to the world’s wealthy. It has already wrapped its brand around all the logical high-value objects.

Doing more in the realm of creating liquidity for the increasing number of folks who see their art as an asset is an obvious place to look next. The fact that Smith mentioned it first in his list of brand extensions during the conference call despite its minuscule size already tells you he has it front of mind.

Nonetheless, Sotheby’s has already expanded its finance revenues by 50% over the last two fiscal years. Even so, the $25 million the financing division contributed to overhead in 2014 was not enough to offset the more than $40m in charges related to the board fight, restructuring and severance for Ruprecht. It will be a long time before financing can have a significant impact on Sotheby’s profits. And yet it will be far greater than what can be generated by those who fantasize that Sotheby’s can extend its brand to “cultural travel or cultural entertainment.”

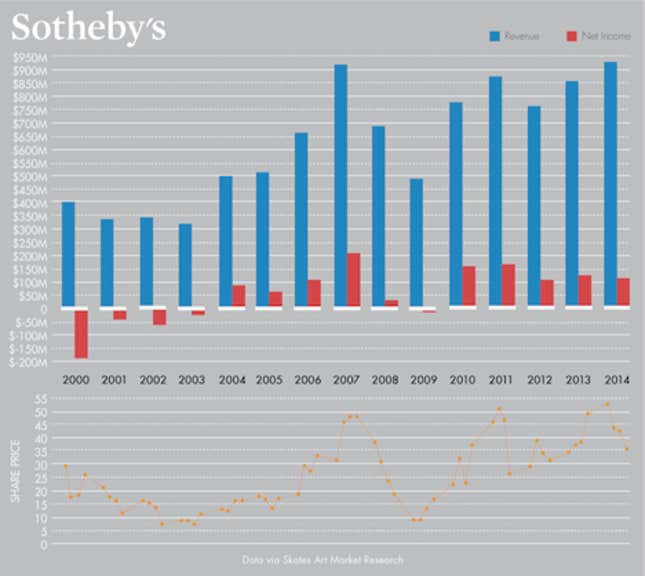

That brings us back to our initial problem. Contrary to what Daniel Loeb thinks about Sotheby’s, there are few untapped markets for the auction house—and lots of competition where it wants to go. Growth may not be in the cards. Just look at what happened during the vertigo-inducing years from market’s initial rise in 2006 to its apex in mid-2008 and then from 2010 to another peak in 2011. No one expected the market to recover quickly from the global credit crisis but it did. Sales volumes have returned to the 2007 peak. Profits have not.

A look at Sotheby’s revenue and profit shows the firm generating more profit in 2010 and 2011 off similar sales volumes than in 2012 and 2013. In 2014, sales reached the previous peak of 2007 but profits were off by almost half. Why? Over the same period, the art market has changed in ways that severely impacted profitability.

Contemporary art dominates the market; a comparatively small number of works—1500 or so—account for nearly half of global sales; and client base has shifted from clubby collectors to a larger but more erratic pool of wealthy buyers. Sales from any location are no longer local. So it is not uncommon for the auction houses to send its best works on a world tour trying to generate interest in Asia, the Gulf States and Russia.

The value of art may be concentrated in those 1500 works that generate 48% of the art market’s sales but for Sotheby’s to get its share of those few works in front of the 200,000 or more persons with liquid assets of $30m or more around the world is getting increasingly expensive. For all of the talk of technology, selling art to the extremely wealthy remains a high-touch business. Buyers, especially new buyers, want to be stroked, supported and coddled before they agree to wire a million dollars or more to Sotheby’s for some pigment suspend in dried oil attached to a canvas. You don’t have to think art is a confidence game to get that many of the new buyers in the art market are interested getting the full Sotheby’s brand experience.

That’s not cheap to provide. The auction house also has to maintain a large staff of business getters and client relations specialists in more and more places. It’s not enough to just expect your buyers to show up in New York, London and Hong Kong. You need smart, attractive, well-dressed and well-connected people out among the new rich letting them know who’s who and what’s what.

Great sales forces are either well-oiled machines or dominated by a few star players. Perhaps Smith and de Sole think they can use technology to reduce the cost of this sales organization and turn it into a humming dynamo. Problems like the drop in private sales are clearly from the loss of stars but it remains unclear how an outsider like Smith is going to be able to quickly or efficiently recruit new standouts to Sotheby’s team.

And can he do it without breaking the bank? Costs are a bugbear for Sotheby’s. And Sotheby’s cost problem doesn’t come from investing in technology or brand extensions. The expense issue lies in the fact that it is a sales organization, a bloated sales organization.

“We spend too much on people, travel, entertainment, client relationships etc.,” one of the Sotheby’s directors wrote to the former lead director whom de Sole replaced. “Don’t know how spending was allowed to get that far out of control … I think Bill [Ruprecht’s] strategy was–revenue and people at whatever the cost.”

If the revenue-at-whatever-the-cost era is over at Sotheby’s, a remorseless cost-cutter with no ties to the industry or particular knowledge of its workings who can aggressively winnow the firm down to size is what’s needed. And this may be the clue we need to understand why Tad Smith is the new CEO.