Over the weekend, Prime Minister Narendra Modi caused a few eyebrows to be raised when he suggested that ancient India must have been skilled in plastic surgery. How else would Shiva have grafted an elephant head on Ganesha after having beheaded the boy, Modi asked, reaching for an example from mythology.

That wasn’t all. Ancient India was also aware of genetic science, Modi said at the inauguration of the Nita Ambani-run Sir H.N. Reliance Foundation Hospital and Research Centre in Mumbai. To back up this assertion, he noted that Karna of the Mahabharata was born outside his mother’s womb.

By citing mythology as factual evidence of scientific progress, Modi seemed to be setting himself for ridicule. Newspapers in India and abroad did not miss the opportunity to take sarcastic digs at the prime minister’s statements, and, as was to be expected, social media users joined in too.

Modi could have spared himself the embarrassment if he’d put aside the epics and reached for some real Sanskrit treatises instead. Had he looked at the Sushruta Samhita,for instance, he would have found a description of one the world’s first plastic surgeries by Sushruta. In his treatise, Sushruta writes about grafting a piece of skin from the cheek to the nose around 600 BCE.

He also lays out instructions for how to reconstruct a nose with a flap of living skin carved from the cheek, treating it with liquorice and sandalwood. Europeans did not perfect rhinoplasty until the 19th century.

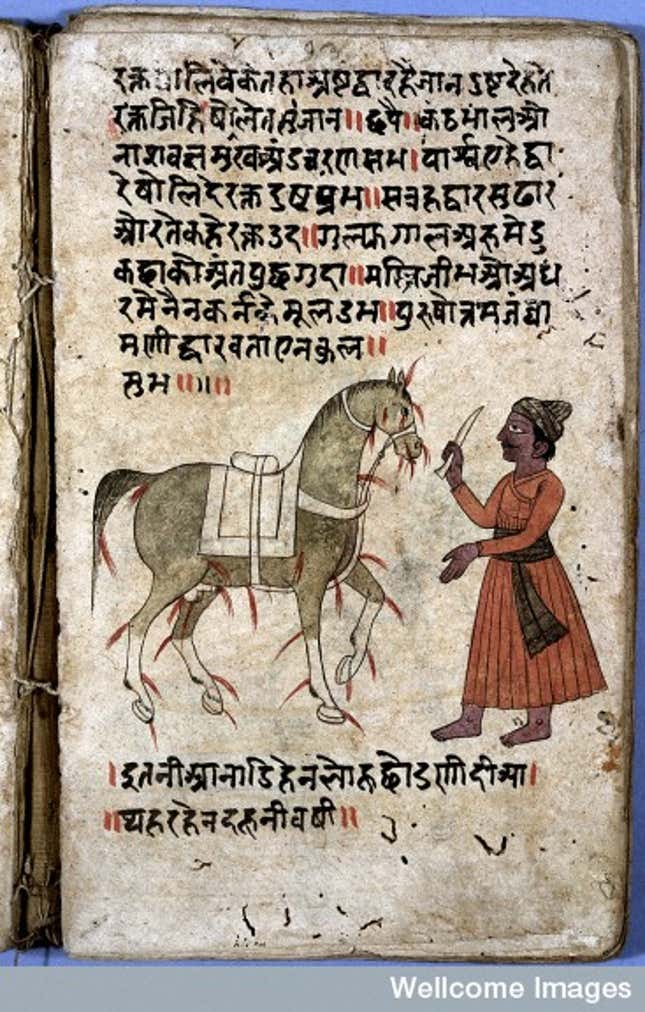

Sushruta was not the first physician from the subcontinent to detail his treatments. Shalihotra, perhaps the world’s first recorded veterinarian, wrote a long treatise on the care of horses some thousand years before that. He not only recommended what medicines to give horses when they were ill, but also detailed surgical procedures such as eye operations and bloodletting.

![Eye operation on a horse. Illustration and text, 18th century. From Salihotra (Hindi): Asvacikitsa of Purusottama [treatise on horses].](https://i.kinja-img.com/image/upload/c_fit,q_60,w_645/8eba4371560a331e4676fe80c7d88ae2.jpg)

As is evident, India has a long and thriving history of medical treatment. Traditional medical systems such as unani and ayurveda, which call for holistic healing, are vibrant in India even today. While they are looked upon with some distrust by western medical practitioners, these practices even have a department under the union health ministry to themselves, AYUSH, which deals with ayurveda,yoga, unani, siddha and naturopathy.

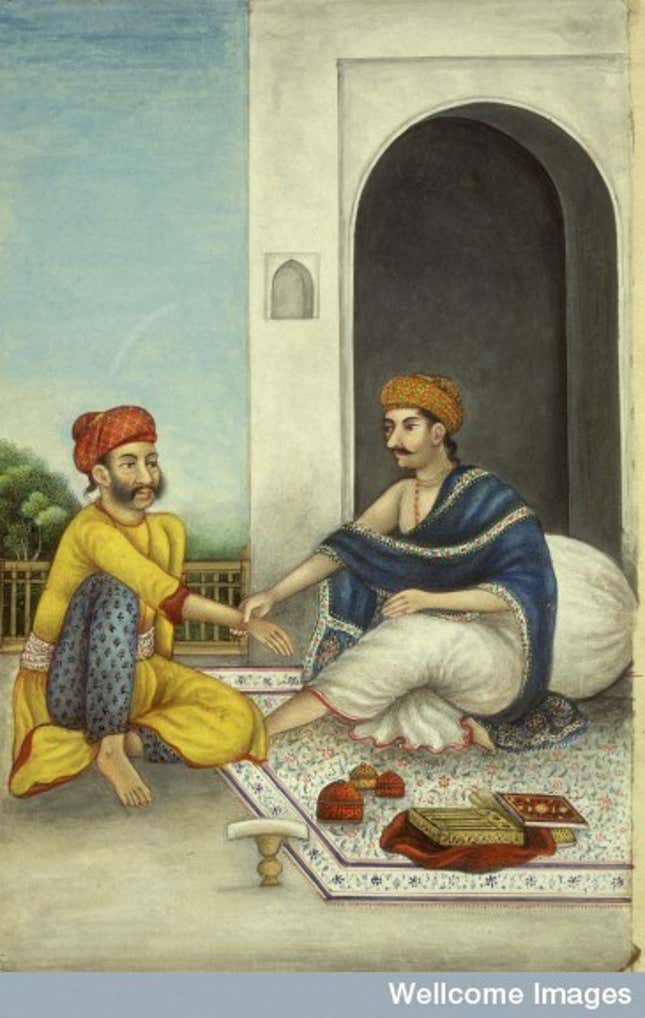

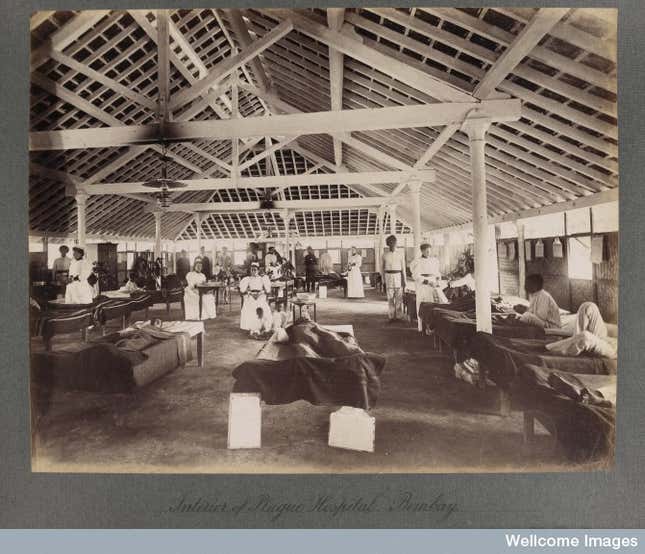

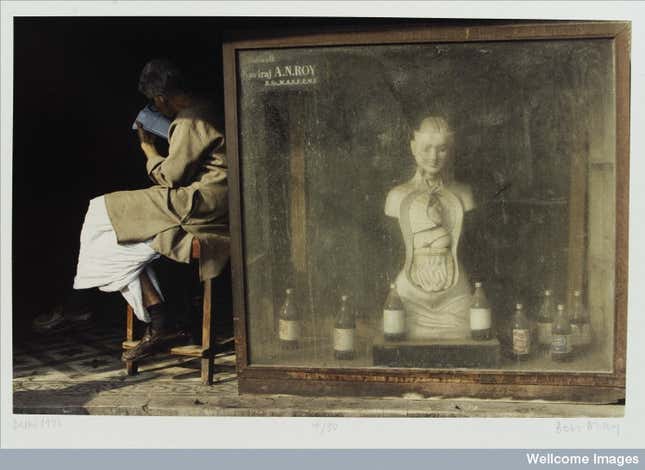

Visual evidence of India’s long medical history can be found in the collection of The Wellcome Trust, a health-oriented international charity based in London, has been collecting images of medical practices from across the world since the 1890s.

The library has over 2,50,000 paintings, prints and drawings, some of which document the subcontinent’s transition from Indian to western medicine, as ear cleaners and surgical veterinarians give way to British-run plague hospitals and informative posters about leprosy. Here is a selection.

![Leprosy: patients showing symptoms. Colour lithograph, [195-?]. By Hind Kusht Nivaran Sangh.](https://i.kinja-img.com/image/upload/c_fit,q_60,w_645/eea81108e0f7694995320b4fc4f14f6a.jpg)

![Leprosy: patients showing symptoms. Colour lithograph, [195-?] By Hind Kusht Nivaran Sangh.](https://i.kinja-img.com/image/upload/c_fit,q_60,w_645/07e8c649e77fe084af4e03b8eaeb1583.jpg)

This post originally appeared on Scroll.in.