This is part of a series on improving mental health research, diagnosis and treatment. Join the conversation on Twitter with the hashtag #OpenMinds

On my hospital bedside table was a photograph of my four-year-old son, Cillian. I looked at his cherubic cheeks and his smiling face, and my heart broke. A few hours earlier, my wife had begged me not to kill myself. She said that she might eventually accept my death but that Cillian would never get over it. I couldn’t bear to look at his picture any longer; I put it in the drawer. Then, I went back to doing what I had been doing for weeks on end – sitting on my bed in a locked psychiatric ward, lost in my morbid thoughts, staring out the window. The building across the street was partly demolished, its exposed, ugly, walls half-standing. I realized that I was like that building: My life was in ruins.

It didn’t used to be like this. Eighteen months prior I was functioning normally. I was working as a television producer in a busy newsroom. I was a devoted husband, an involved father, cracking one-liners in the office, on top of the bills, working out like a demon. Things changed in June, 2011, when a cancer diagnosis knocked the wind out of me. I had Stage III melanoma with a six-in-10 chance of being alive in five years. Not the best odds, but not the worst either. After three surgeries I was deemed what oncologists call “NED” – no evidence of disease. Melanoma has a nasty habit of coming back, however.

In November, 2011, I started an immunotherapy treatment called interferon, which would reduce the risk of a recurrence. Interferon is a brutal, year-long regimen with punishing physical side effects, such as fatigue, chills, nausea, loss of appetite and low white blood cell count.

My oncologist also stressed I would be monitored closely for depression, which occurs in about 40 per cent of patients. “If you become depressed, please let me know,” she said.

“Yeah, right,” I secretly scoffed. “Depression? Me? Not going to happen.”

In a sense, my arrogance was well founded. I had no history of depression. But it ran deeper than that – I didn’t really even understand it. If you had asked me to describe depression back then, I probably would have likened it to feeling sad, or being in a funk. I certainly had little sympathy for those that suffer from it. While I had some trepidation about the physical test I was about to face, mentally, I felt bulletproof.

I tolerated interferon well for the first six months, although not without side effects. My energy levels dipped; I lost my appetite and, with it, 30 pounds. Then, nine months in, out of nowhere, I started having bouts of insomnia. Anxiety began keeping me awake for half the night.

In October, my oncologist suggested I stop treatment because of signs of depression. But eight weeks from the finishing line, there was no way I was going to agree to that. The only thing I cared about was keeping my cancer at bay – mental problems be damned.

In November, things spiralled. I started missing entire nights of sleep. Unable to function at work, I went on disability leave. I had severe panic attacks and I began to have suicidal thoughts. I was unwittingly locked in a Catch-22: Staying on interferon gave me the best odds of beating my cancer. But the drug itself was slowly killing me.

With only two weeks remaining, I quit treatment. It was deflating not to make it to the end. But I had a much bigger problem on my hands: I was in a full-blown clinical depression.

I desperately wanted relief but there was no end in sight. My oncologist told me that interferon could take months to clear out of my system.

I was put on an antidepressant and a benzodiazepine, which, despite being highly sedating, did little to ease my out-of-control anxiety and insomnia. My depression was so all-encompassing that it culminated in a complete loss of self.

As fall morphed into winter, I stopped functioning entirely. I withdrew from every single thing that made me who I was. Everything in life overwhelmed and exhausted me. I felt unbearable pent-up tension that I could not release. At night, I would black out for an hour or two and wake up, soaked in a cold sweat. Then, I’d lie there for hours, uncomfortable and wet, suicidal thoughts racing through my head. The lowest and loneliest I felt was when early morning light drifted into the room and I’d realize yet another night had slipped by unslept. During the day, I had so much time to fill, but no desire to do anything.

THE WORST KIND OF PAIN

Depression is one of the worst kinds of pain: There is no relief. After my cancer surgeries, I had been in quite a bit of physical pain, but I’d pop an OxyContin and I’d feel better almost right away. There is no oxy for depression. When I was put on an antidepressant, I was told it would take at least six weeks to start working – if at all. I didn’t think I’d be alive in six weeks.

I considered methods of killing myself on hundreds of occasions. I thought about hanging myself from the rafters in my basement, asphyxiation via carbon monoxide poisoning in my car. I paced around the neighbourhood and considered throwing myself in front of a bus. Every time I rode the subway, I thought about jumping in front of a train. Drowning seemed like the best option of all – I’m a weak swimmer so it would have been almost a sure thing.

I shut almost everyone out of my life. I desperately wanted to engage with my son, but couldn’t. Cillian would be pushing a toy truck in the hallway and I’d step around him as if he wasn’t there. The only person I let in was my wife, Helen. I clung to her as my lifeline. But all she got in return was despondency. She spent hours trying to reason with me, telling me that I’d pull through. When my mood dipped particularly low, she would gently ask me if I wanted to go to the hospital. I would stubbornly shake my head. In truth, it was something that I had started to consider. Hospital had a strange pull for me. I felt like it might offer a refuge of sorts.

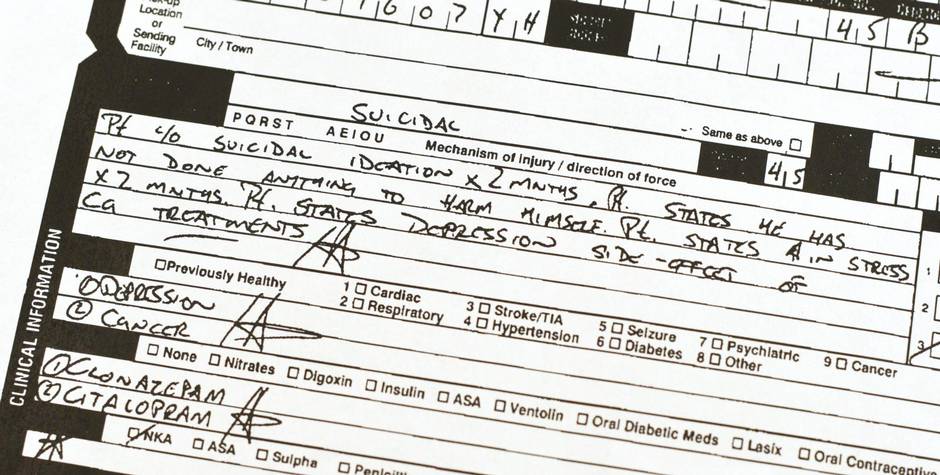

By January, it was clear I wasn’t getting any better. One night, I turned to Helen and said “I can’t face another night.” She called 911 and within 30 minutes we were sitting in Toronto General Hospital’s emergency room. We waited hours to be seen. Around 5 a.m., an exhausted psychiatrist saw me. I told him I was suicidal, and if he didn’t admit me I would probably kill myself later that day. My admission sheet to the psychiatric ward said: “Major depressive disorder with suicidal ideation. Severe.”

When I arrived on the 8th floor of Toronto General, the atmosphere was oddly serene. The ward was bright, airy and clean. It calmed me. Since it was a Sunday afternoon, the hospital was ghostly quiet. I puttered around for a while but grew tired. Eventually, I went to my room and climbed into bed. The silence was broken only by the melancholy weeping of a depressive in the room next to mine. I felt a certain peace and relief: I was in safe hands and experts who knew a lot more about depression than me, who had helped others get better, would surely be able to fix me. Little did I know how relentless my illness would prove to be.

The hospital offered various group therapy sessions, which I was optimistic about at first, but my enthusiasm quickly waned. I could have benefited from intensive one-on-one talk therapy, but that’s not the reality of care in a public hospital in Canada. Instead, I had one “Introduction to Cognitive Behavioural Therapy” group class a week, which was laughably inadequate.

I can say with absolute confidence that I was one of the worst students of art therapy to ever grace the halls of Toronto General. Even in a compos mentis state, sitting in a room and being asked to produce a piece of “art” would be tedious – having to do it whilst being actively suicidal was agonizing.

What I found illuminating (and sometimes horrifying) in group therapy was hearing about other patients’ experiences. A paranoid schizophrenic recounted how he had recently jumped into Lake Ontario in the dead of winter because he was convinced that he was being followed. A severely depressed lady in her 60s, clad in a pink robe and slippers, claimed that she hadn’t slept in eight years. I wondered if I was heading down that path myself.

My insomnia was a code that proved impossible to break. The only time I slept was when I was put on Seroquel, a powerful antipsychotic, for a few days. A dose would knock me out for about 90 minutes, but would also induce disturbing dreams. Occasionally, I would pace the ward at 3 a.m. – anything to break up the endlessness of the night.

Any vestiges of normalcy that I was able to maintain on the outside went away in the ward. I gave up every hygiene habit, including showering and brushing my teeth. I walked around in a slow, plodding fashion, like an old man on his last legs. My mind was muddy. Sometimes, I’d begin to talk and stop mid-sentence, unable to finish. I became increasingly solitary. The only people that I allowed to see me in hospital were my wife and son.

Cillian was a bright light in a grim place. When he came to visit me in “my apartment,” as he called my room, he was always impeccably behaved and uncharacteristically low key – the nurses loved him. Somehow he seemed to know something was seriously wrong. We told him that I was in hospital because “my head hurt.” Every night, he would ask my wife if I was coming home. I was convinced he would eventually stop asking, but he never did.

Helen came to see me every day, with two exceptions: The day of her grandmother’s funeral and when the subway broke down while she was on her way to see me. She became such a familiar face around the ward that a patient asked her how she liked working at Toronto General. She came despite holding down a job, taking care of my son, running the house and the million other things normally functioning people do every day. She would sit with me for hours and talk. She’d bring freshly baked cornbread or homemade lasagna that I’d barely touch. She brought fresh clothes. She cut my hair. Sometimes we’d roam the hospital grounds, hand in hand, like a couple of lost souls. She never stopped believing that I would get better. My relentlessness and hopelessness didn’t break her. She never blinked. She told me she would never let me go.

When I was first hospitalized, only a handful of people knew where I was. That’s the way I wanted it – I didn’t want people to know I was in a “nuthouse.” But as the weeks went by, I knew that it was futile to keep it a secret and that it was unfair to Helen to shoulder the burden. So, I told a few friends. Then, I told my boss. I held out the longest in telling my family back in Ireland. From my hospital bed, I called my mother: “Mum, I’m in the hospital being treated for depression. And you know what kind of hospital I’m talking about.” She took it surprisingly well and assured me that I would get better. She was, however, adamant that she would tell no-one (her insistence, not mine). Evidently, she changed her mind – 30 minutes later, a text came in from my brother Owen, the town gossip. At that point, I was pretty sure that a good chunk of the population of the northwest of Ireland was aware of my new living arrangements.

THE DECISION TO LEAVE

Once I passed the one-month mark in hospital, I felt it was time to admit something fundamental – my depression was treatment-resistant. After 37 days, I was discharged from Toronto General Hospital’s psychiatric ward. There was no movie ending for me. I returned home still very much mired in a serious depression. My psychiatrist suggested I increase the dosage on my antidepressant. But I had grown cynical: I had tried many different drugs and dosages but nothing was working. In fact, I suspected the meds were making my condition worse. Many of the side effects of psychiatric drugs are also symptoms of depression. Were my feelings a symptom or a side effect? I was starting to believe the latter.

The way I saw it, all the talking, the group therapy sessions, and, especially, the many drugs that I had tried had little effect. I felt like I was fighting a nuclear war, but that psychiatry had given me only bows and arrows to defend myself. A few days after returning home, I stopped taking my medication. I told no one. Not even Helen. I was so angry that nothing had worked that, in an act of juvenile defiance, I threw all my drugs in the garbage. I was aware of the possible side effects of cold turkey withdrawal from psychiatric medication: insomnia, extreme anxiety, depression, elevated risk of suicide. But, the way I saw it then, there wasn’t really any downside – I was already living with all those side effects.

For the first week or so, I didn’t feel any difference. And then something unbelievable happened. In early March, over the course of a week, I went from being clinically depressed to having almost no symptoms. My anxiety melted away. I was able to sleep about five hours a night. Deep reserves of energy returned. My concentration came back. I could read. I was able to follow the plot of a TV show. I could write. I could take my son to the park. Soon, I was back in the gym working out with Rafael Nadal-like intensity. Whether my recovery was a result of quitting psychiatric medication, or simply interferon finally leaving my system, I will never know for sure.

The weeks and months that followed were the happiest of my life. I tried to get caught up on everything that I had missed. I called friends and family and talked their ears off. My appetite was back and I regained much-needed weight on my emaciated frame. Cillian and I spent many hours running around like monkeys escaped from the zoo. In the fall, I returned to work and within a few weeks I had settled back into a familiar routine. My family had come through a great crisis. Somehow we were all intact.

ON THE OTHER SIDE

Every single day I wake up and realize that I’m no longer depressed is special. I feel relieved, grateful and optimistic. It never gets old. But going through a serious depression and coming out the other end is a funny thing. One does not end up with a dramatically new personality, nor does one necessarily become a better person. I’m still impatient, annoying and selfish, and the little things – like the printer jamming at work – frustrate me as much as they always did. But the experience is akin to how I imagine being a plane crash survivor might feel. At one point you absolutely thought your life was going to end, but you survived. Nothing and everything changes at once.

One thing that has changed is my understanding of depression and empathy for those who suffer from it. Depression, I have come to realize, is very real, absolutely debilitating and there are no quick fixes. Don’t ever tell a depressive to go for a run, or to take a zumba class. You may as well be asking that person to climb K2 and snowboard their way down. What people need is compassion, patience and a willingness to stick with them.

Recently, someone asked me what it feels like to be a cancer survivor. I answered that I wouldn’t know, because I’m not a cancer survivor – at least not yet. I am still in that five-year danger window, where the risk of my cancer coming back and finishing me off remains high. It is too early to say whether interferon, the drug that almost killed me, will in the long-run save my life. But, in the interim, I will admit that I do try to squeeze a little extra out of life. I sleep less and live more than before.

Earlier in the spring, I returned to the psychiatric ward for a visit. It was my first time back since I was discharged more than two years ago. I recognized a kind nurse who had treated me. I asked her if she remembered me. A warm smile came across her face. “I never forget a patient.” she said. She said she rarely finds out what happens to patients after they leave. She was so happy to see me and to learn that I was well. We spoke for a few moments. Then she shuffled off quietly on her rounds.

Niall McGee is a reporter for Report on Business. Follow him on Twitter: @NiallCMcGee

ANTIDEPRESSANT WITHDRAWAL

Quitting antidepressants cold turkey is risky. Within a day or two, people who suddenly stop taking these drugs may feel irritable, anxious or depressed. They may suffer from headaches, nausea, dizziness, fatigue, insomnia and flu-like symptoms, according to the Mayo Clinic.

But the greatest risk is self-harm. Patients are more likely to commit or attempt suicide within the first 28 days of quitting antidepressants than at any other time during antidepressant treatment, according to a 2015 study of 240,000 people published in the medical journal BMJ. Higher rates of self-harm in the first 28 days of stopping and starting antidepressants “emphasize the need for careful monitoring of patients during these periods,” the authors wrote.

Mood changes and physical complaints are symptoms of antidepressant withdrawal. Antidepressants are not addictive, but they do alter the body’s chemistry. Going off them abruptly does not give the body enough time to adjust to these biochemical changes, said Dr. Ana Andreazza, an assistant professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto.

Some patients quit antidepressants because of early side effects, such as dry mouth, nausea or anxiety. “These side effects should be addressed with a doctor,” she said.

Others stop taking antidepressants because they feel better, or want to explore drug-free approaches, such as exercise, dietary changes or psychotherapy. But Andreazza cautions against making the transition without consulting a doctor or psychiatrist.

A doctor can help the patient taper the dose over a period of weeks to give the brain a chance to adapt, and assess how he or she is coping as the drug leaves the system.

Most people would not go off blood pressure or heart medication without talking to a doctor, Andreazza pointed out. “So why would you do that with a drug that affects brain functioning?”

— Adriana Barton

INTERFERON AND DEPRESSION

Interferon medication is a known trigger for depression.

Used to treat melanoma, leukemia and hepatitis C, interferon drugs mimic naturally occurring proteins secreted by immune cells.

Interferon therapy made headlines in the late 1970s and early eighties as a magic bullet for cancer. But clinical trials dashed these hopes, and revealed side effects including flu-like symptoms, diarrhea and depression.

Up to 40 per cent of patients may develop interferon-induced depression. Symptoms may be mild to severe, said Dr. Steven Dubovsky, chair of psychiatry at the University at Buffalo, State University of New York. “It looks just like any other kind of depression.”

Researchers theorize that interferon activates genes that disrupt communication between neurons and turn off genes that protect the brain.

Normally, depression symptoms lift “as soon as you stop the treatment,” Dubovsky said. But, in some patients, brain changes may persist for weeks or months after the drugs have left the system.

Interferon-induced depression is more common in patients with a past history or family history of depression. For these patients, doctors will prescribe an antidepressant as a preventive measure.

Patients without a history of depression are monitored for depression symptoms throughout interferon treatment. If depression is severe, doctors may take the patient off interferon therapy. Adriana Barton

But in most cases, patients will recover from interferon-induced depression after trying different dosages and types of antidepressants, Dubovsky said.

— Adriana Barton

The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health has purchased advertisements to accompany this series. The organization had no involvement in the creation or production of this, or any other, story in the series.