The insults are crude, but they hit home hard.

Shi**y African. Shi**y black people.

The players of Koa Bosco have suffered many such racist taunts since their football club was formed in 2013.

On occasion, physical violence has even flared on the pitch, says the Italian team’s manager Domenico Mammoliti.

“The ignorance of some people…” he sighs, revealing a hint of exasperation at the abuse he says his players have endured.

Life in the Italian lower leagues is clearly tough.

Yet it’s nothing compared to the journey undertaken by this team of African immigrants and refugees from countries such as Ghana, Senegal, Gambia, Burkina Faso, Mali, the Ivory Coast, Togo and Sudan.

Many risked their very existence crossing the Mediterranean Sea on rickety boats, often fleeing war, poverty and persecution in search of a better life in Europe.

The U.N. Refugee Agency estimates that more than 3,500 people perished making the same journey in 2014. This year, 1,850 are believed to have died out of roughly 100,000 people who have attempted the crossing.

And for most of those who do make it, life in Europe is hardly a paradise of milk and honey.

Work away from the football pitch for most Koa Bosco players consists of picking fruit on farms for a paltry wage, Mammoliti said. And they are the ones lucky enough to find employment.

A perilous journey

Koa Bosco midfielder Almani Camara, originally from Gambia, told CNN that he arrived in Italy after boarding a smugglers’ boat in Libya.

Camara said he risked the trip as he “doesn’t hear any gunfire” or “see any dead people” in Europe as he did in Libya.

His vessel was crammed full of people from all over Africa and had to be rescued after running into what he describes as “difficulties.”

The journey, he admits, could have easily have ended in tragedy – yet still the migrants flock to Europe.

CNN’s Christiane Amanpour witnessed a packed boat intercepted by the Italian navy close to the Mediterranean island of Lampedusa only last month. One person had died after suffocating on the ramshackle wooden boat while three people had to be medevaced off.

Such horrors all too familiar to the players of Koa Bosco.

But the last few weeks have provided a welcome distraction from harder times and memories of struggles elsewhere.

After just two years of existence, the team based in the southern town of Rosarno – situated in the Calabria region which forms the toe of Italy’s geographical “boot” – achieved promotion from the bottom tier of the country’s football league pyramid.

It was a triumph so unlikely that Mammoliti said he’s still trying to convince himself it actually happened. “I had one of the greatest emotions of my life,” he says. “It was a true miracle.”

For Camara, it was a victory forged in togetherness and teamwork against an adversity that went way beyond sporting competition. “They tried to fight some of our players,” he said of the sides Koa Bosco faced over the course of the season. “(But) to win made us very happy.”

Koa Bosco will now play in the non-professional Segunda Categoria which comprises higher caliber teams from the wider Calabria region. The Segundo lies seven levels below Serie A, Italy’s top division.

Although there may still be a long way to go reach the likes of Juventus, AC Milan, Roma, Lazio and Internazionale, the success marks an incredible beginning for what is essentially a church team.

Humble beginnings

The club was founded by Mammoliti, his colleague Domenico Bagala and a priest named Don Roberto Meduri before entering the Italian Football Federation last year.

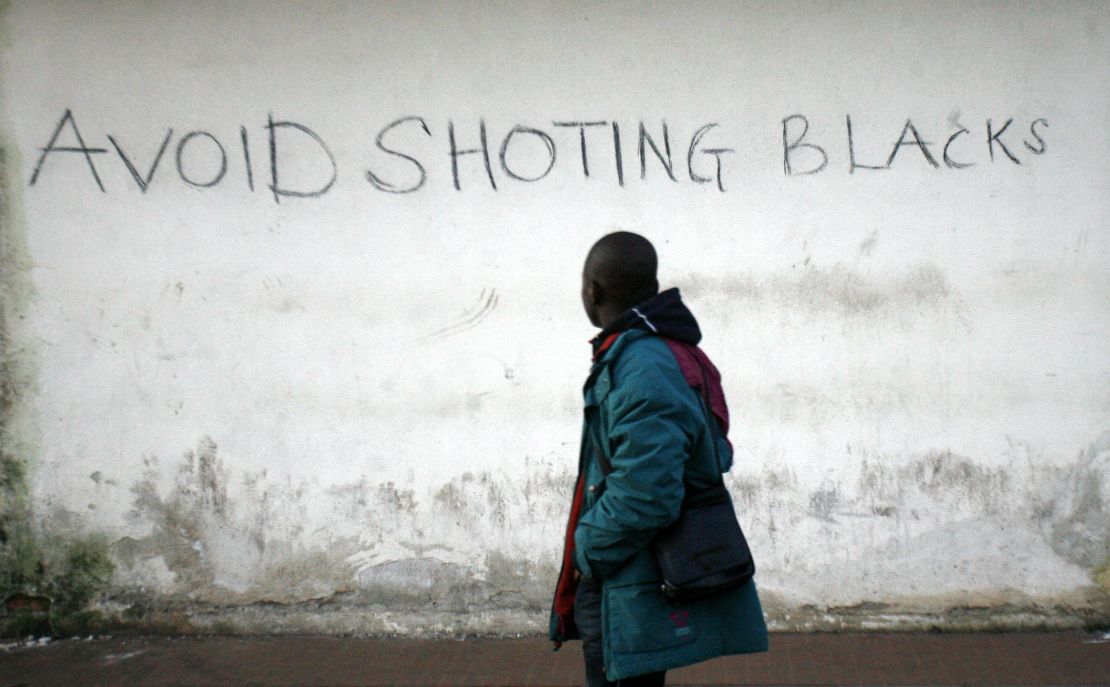

Its aim was to bring attention to the plight of migrants arriving in Italy. Rosarno itself has experienced its fair share of racial tensions in recent years. In 2010, days of rioting followed the shooting of an African migrant.

In the hours and days after, many migrants were evacuated from the area. CNN even reported that a van was touring Rosarno blaring out the message: “Any black person who is hiding in Rosarno should get out. If we catch you, we will kill you.”

Koa Bosco’s achievement is all the more notable given this history, not to mention the legacy of troubles faced by the players in their home countries.

“They (the players) don’t know the language very well,” Mammoliti says. “They don’t have means of sustaining themselves or making enough money.

“Many of them come (to Europe) for family reasons, because they were poor, because of wars in their own countries or because of some sort of struggle with the Islamic laws or the tribes that were in control of their territories.”

Support has come from a number of people in the local community who have followed the team home and away, often donating money and food.

But Mammoliti explains that Rosarno’s response to Koa Bosco hasn’t always been positive. Although there are many who applaud what they have done, others “have reacted with ignorance.”

This continuing battle has led Mammoliti to step down as manager of Koa Bosco and help set up another new club that aims to field African migrants and local players together.

Mammoliti sees many similarities between the people of Calabria and migrants from Africa. “Our kids have no work, no hope,” he says. “They expatriate to find something more promising.”

Calabria is already one of the most depressed regions in Italy. Unemployment reached 23.4% in 2014, according to data collated by Eurostat, ensuring the influx of new arrivals from Africa has put further strain on the region’s social fabric.

Mammoliti hopes the new club, which he says will be called San Michel and has been founded alongside another local priest named Don Gaudioso, will help preach a message of tolerance and integration among the people of Rosarno and beyond.

Black and white together

“Together we can get to the goal of … putting the local kids and the Africans together in a group,” he says.

“They (migrants) are paying the price of disinformation and ignorance because Italy is in the middle of severe crisis and we blame the black man.”

Mammoliti’s words are indicative of the wider political debate regarding immigration currently raging across Europe.

Some even suggest Europe has a historical debt given the often brutal colonial record of Britain, France, Germany and Italy in Africa.

There’s almost certainly more to this complex, multi-layered issue than that. Yet geographic location puts Rosarno, Calabria and Italy on the front line like few other places when it comes to dealing with the consequences.

As such, showing tolerance and creating an example of understanding between communities which others can follow will continue to be the primary goal for the founders and management of Koa Bosco.

Even more so than performing another miracle by rising up further through the Italian leagues.

Do you have any inspiring football stories? Let us know on CNN FC’s Facebook page

CNN’s Jacopo Prisco contributed to this story