Google Joins the Search for the Loch Ness Monster

Now anyone with an Internet connection can search for Nessie using Street View imaging of murky Scottish waters.

The tale of the Loch Ness monster has always been, in a funny way, a story about technology. More specifically, it is a story about how machines can bump up against the edge of a mystery, and provoke a sense of wonder that eyewitness testimony cannot.

There's the famous photograph, of course. Grainy, black-and-white, with the silhouette of a creature sloping into the rippled water. When it emerged in 1934, the Surgeon's Photograph, as it's known, caused a sensation. It was later revealed to be a hoax in what has become a long tradition of elaborate, made-up images of the monster.

There would be other photos. There was also a film, which showed a beast with a humped back and a long black tail splashing wildly as the creature apparently propelled itself with fins. Last year, there was debate over whether an image from Apple Maps featured the elusive monster.

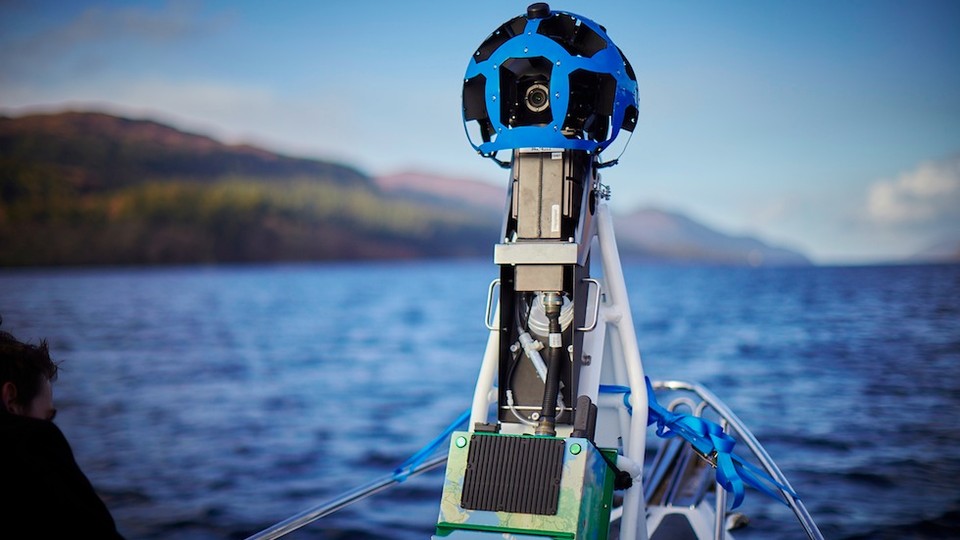

And now there is Google Street View footage—or, loch view, in this case—which doesn't promise a sighting of Nessie, but does provide plenty of imagery for amateur monster-hunters to scour. In honor of the 81st anniversary of the Surgeon's Photograph, Google mounted its imaging equipment on a boat—plus took underwater photographs—and stitched together a portrait of Loch Ness by taking photos every 2.5 seconds.

Google also partnered with Adrian Shine, a man who has examined more than 1,000 monster sightings. "He helped us go through the imagery," said Deanna Yick, who is a program manager for the Street View team. "There are some very interesting images where the way the light hits the waves on the water, you're not really sure." (Yick's take on the question of Nessie's existence: "I believe anything is possible.")

There are a few reasons why the story of the Loch Ness monster has persisted for so many decades. For one thing, it's hard to prove a negative. And particularly hard when, as the Google underwater footage shows, the water of Loch Ness is so cloudy.

"We knew that at Loch Ness, because of the peat content of the water, which makes it more murky than normal, that it would be difficult to see," said Yick. "That adds to the experience."

But the Loch Ness monster, conceptually, is also a way of talking about what humans don't know—and, more specifically, about how what we don't know can actually be big, and astonishing, and very often slips by us undetected. This is why, in the vast and entertaining world of livestreamed animal cams—bear cam, kitten cam, sloth cam—perhaps none is so anticlimactic as the Nessie cam. Not only because the monster inevitably fails to show up, but because the popular appeal of the Loch Ness monster is the idea of the thing. The notion that Nessie's existence can't be proved or disproved—not based on human accounts, nor by technological ones—calls into question our reliance on the tools we use to look at the rest of the world. And that kind of uncertainty is useful, actually.

Which brings us to the other reason the story of the Loch Ness Monster has endured, despite all rational inferences to the contrary, despite science journals like Nature declaring the monster to be "a large gray seal." People like not knowing. The thrill of discovery is fleeting. Knowing something for sure only raises the next set of questions. But the appeal of possibility has a curious way of lingering.

In the past century, there have been several theories about what the Loch Ness monster actually was. If not an elasmosaurus, somehow splashing about in the Scottish Highlands 80 million years after the rest of its species receded into geologic time, perhaps it was a giant squid, or a seal, or a hippopotamus, or a crocodile. One photo said to depict the monster looked "remarkably like that of a drifting tree trunk," The New York Times reported in 1934, at the height of the Nessie craze.

At that point, "Nessie" wasn't even the monster's nickname. The serpent was, for a time, affectionately called "Bobby." Again from the Times in 1934:

Bobby... is equally at home in fresh water and salt water, which means he resembles the Swedish 'monster' of 25 years ago. This creature inhabited Lake Storsjon and, like Bobby, received a name. He was addressed familiarly as 'Storsjoodjuretuppenbarelserna,' but disappeared without leaving evidence of his actuality.

Where the tale of Storsjoodjuretuppenbarelserna apparently stalled out, stories about the Loch Ness Monster endured—and in part because claims of documented sightings continue to trickle out as new technologies are adopted. Decades of debate over a single photograph gave way to questions about whether the monster might be detected through hydrophone recording, satellite imagery, and camera-phone footage.

Actually, the technological significance of Loch Ness precedes that of the monster sightings. In 1894, Loch Ness was the site of an experiment in wireless telephony. It was there that scientists first proved that speech could be transmitted across the distance of the lake—about a mile and a half. It's possible that other technologies have played a role in the story of Nessie over the years. That's been the case in other serpent stories anyway. In 1934, a letter to the editor of The New York Times told a story of a monster that was said to look much like Nessie, but apparently lived in Silver Lake, New York. When someone shot at the creature with a rifle, the letter writer said, it collapsed. "Upon examination it was found to be made of rubber, and anchored so that when it was pulled down by wires it was submerged, and when it was released it came up," the person wrote. "The thing was kept for many years in the attic of an old hotel at the lake as a souvenir of one of the best publicity stunts of the time."

Of course it was. People routinely use technology to project the things they want to be true. They manipulate photos, and analyze the same meaningless seconds of film a thousand times, and, apparently, rig up an elaborate fake monster to bob in actual waters. People also have a tendency to sometimes trust technology more than they trust one another because technology promises to be objective. But it isn't. Technology can be glitchy and imperfect and, most revealing of all, human operated. Or, more pointedly, as the British anthropologist Sir Arthur Keith put it: "I have come to the conclusion that the existence or non-existence of that 'monster' is not a problem for zoologists but for psychologists."

Rationality has hardly deterred those who choose to believe. It certainly hasn't changed the great monster tales that humans have spun for centuries. Like the Norwegian pastor who, in 1734, saw a sea-serpent with a long sharp snout and broad flippers that "blew like a whale," according to a New York Times tally of sea-monster sightings in early coverage of the Loch Ness monster. Or the monster spotted off Gloucester, Massachusetts, in 1817, that had a turtle's head on a long flippered body and could swim a mile in two minutes. Or the huge serpent—60 feet visible on the surface of the water—spotted in the waters around the United Kingdom in 1848. Or the Conception Bay, Newfoundland, creature that attacked a boat until sailors used a hatchet to cut off one of its limbs in 1873. Or the serpent that apparently strangled a sperm whale near Cape São Roque in 1875.

It's easy to decide that the Loch Ness monster doesn't exist. But that doesn't change the appeal of the question: Wouldn't it be marvelous if it were real?