When Ladi Netimah heard the news that Muhammadu Buhari had won the historic elections in Nigeria this week, she didn’t think about how she had languished in a jail cell for almost four years when his military regime cracked down on human rights in the early 1980s.

Instead, Netimah, one of hundreds jailed by Buhari during his rule as an iron-fisted dictator, was thrilled for her former tormentor.

“I forgave him years and years ago,” said the businesswoman, whose jail sentence was imposed by a secret military tribunal after she broke a law forbidding civil servants from running private businesses. “I think he has the good of Nigeria in his heart. He wanted to change Nigeria so much that he went about it the wrong way the first time because he was young and overly enthusiastic.”

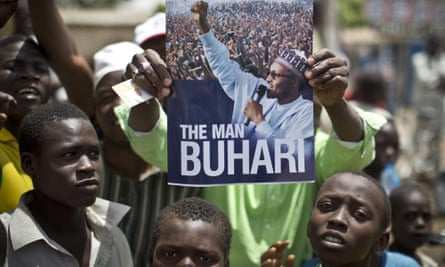

Buhari’s 18-month coup, starting in December 1983, ushered in almost two decades of military rule in Nigeria, each regime more corrupt than the last. But ironically his authoritarian image worked in Buhari’s favour during this year’s democratic campaign, helping him to a landslide victory.

Alongside imprisoning journalists and activists under a series of Orwellian “decrees”, Buhari is best remembered for his “war against indiscipline,” during which he executed drug traffickers, fired civil servants who turned up to work late and ordered soldiers to whip people who didn’t form orderly queues at banks and bus stops.

Despite this, Netimah’s support remains resolute: “In London, Nigerians don’t need somebody to tell them to queue but as soon as they get here, they can’t form an orderly queue. When you hear the name Buhari alone you jump. Maybe that’s what Nigeria needs to become disciplined.”

Others who have come out in support of Buhari include Tunde Thompson, a journalist who was jailed in 1984 under draconian press laws, and Ismail Lawal, whose father was executed by the junta for drug trafficking.

But the fact that a 72-year-old former dictator has become the first to unseat an incumbent reveals both how far Africa’s largest democracy has come, and how far it still needs to go.

Buhari has presented himself as a born-again democrat who possesses the experience to steer the country through instability, currency woes and rampant corruption. He comes into power at a time when many Nigerians have watched corruption become pervasive, while the wealth from the country’s 2m barrels-per-day oil industry has rarely trickled down to the masses under the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) which has ruled since democracy was established in 1999.

At the headquarters of Buhari’s All Progressives Congress, a giant poster portrays him as a smiling, elderly statesman. Emblazoned across the front is the message: “What an elder sees sitting down, a young man who climbs an iroko tree still doesn’t see.”

Mohammed Idris, among those dancing beneath the beaming poster, nodded as he surveyed the message. “It’s true. He’s the only one who is strong and experienced enough to stamp out [Islamist extremist group] Boko Haram,” he said, a reference to Buhari’s crackdown on Chadian rebels in the 1980s.

Goodluck Jonathan, the first president since a return to civilian rule who had no significant ties to the military, has faced sharp criticism for his handling of the Boko Haram crisis, which has erupted during his five-year tenure as leader.

Nigeria’s tensions are often painted as existing between the largely Muslim north and Christian-majority south, but a win that blurred those fluid lines points to a maturing democracy.

“Even before, a president from a minority [ethnicity] like Goodluck could never have won unless the whole country came out,” said Reginald Lawan, a security guard in Abuja who spent two days following the results intently on the cracked screen of his mobile phone. “Look at me, I’m a Christian but I voted for [Buhari]. Whether you are a Christian or a Muslim president, you can still provide.”

But nor have ethnic politics been entirely absent.

Rebecca Preye, from Jonathan’s village of Otuoke, recoiled with horror at the idea of voting Buhari. “I can never vote a Muslim – never, never, never! They will impose sharia law and then this country is finished,” she said, producing a bible from her handbag.

Yet like millions of Nigerians, she showed little enthusiasm for the incumbent either, indicating that Jonathan perhaps lost the election as much as Buhari won it. Voter turnout hovered at around 45% in many of the states which previously threw their weight behind the PDP.

Amachree Oliver queued for more than seven hours to cast her vote in Benue state, which swung from the ruling party to the opposition. “As I was standing there, I was feeling sad because last time I was waiting this long for Jonathan,” Oliver said. “But then I realised God’s plan had been to use Jonathan to ensure a peaceful handover. At least he achieved that much.”

Bad timing has also played its part. Jonathan inherited the country at a point when global oil markets crashed, badly damaging Nigeria’s oil-exporting economy.

Much is also down to Nigeria’s changing demographics. More than 70% of its 170 million-strong population are under 30, and will not have been born during Buhari’s 18-month rule. Instead, their first real taste of him may have come through his slick social media campaign – an area in which his rivals lagged behind.

“The PDP just didn’t know how to adapt,” said Folarin Gbadebo-Smith, of the Lagos-based Center for Public Policy Alternatives. “Things were shifting online in a globalised world but they were still reading from the old rule book.”

Some see worrying glimpses of Buhari’s authoritarian nature in his initial refusal to accept the results of the 2011 elections. That led to thousands of his supporters taking to the streets in a week of bloodshed that left more than 800 dead.

Others are alarmed at the almost cult-like reverence that has built up around Buhari.

“I don’t like that the language of a messiah has come. People tend to get carried away, that’s going overboard completely,” Nobel prize-winning author Wole Soyinka told the Guardian. “If Buhari’s coming back, he’s got to recognise that he has a debt to pay.”

Not all those who suffered from Buhari’s heavy-handedness can forget as easily. Yeni Anikulapo-Kuti, the eldest daughter of Afrobeat pioneer Fela Kuti, remembers how her father was arrested in 1984 on currency smuggling charges that his family saw as bogus. She was 23 at the time. “I remember that day like it was yesterday,” she said. “I was in tears, I cried, it was a very terrible situation. I remember going all the way to Maiduguri to see him prison but we were not allowed.”

The judge who had sentenced Kuti later went to see him and, according to Yeni, admitted that he had been acting on Buhari’s orders. “I believe it was for political reasons because Fela had previously testified against Buhari.”

Buhari was ousted the following year and Kuti was freed. Yeni, 53, now a TV presenter and co-owner of the New Africa Shrine, a club modelled on Kuti’s spiritual home in Lagos, could not bring herself to vote in the presidential election that saw Buhari returned to power.

“As a true Nigerian I can only hope he will move the country forward. It’s not about personal animosity. I will have to put that to one side, although it will remain there. But let’s hope he does the people proud and they won’t regret voting for him.”

She is far from alone in remaining unconvinced by the new leadership. Many veteran politicians have also flip-flopped between the two parties. “For me what would be really positive is for intelligent Nigerians to vote for one of the smaller parties, new faces,” said Ify Ojuoke, a banker in Abuja. “I’m not sure there is much to celebrate in voting a 72-year-old who has kept coming back – one, two, three, four times – to taste power.”

Even among fervent Buhari supporters, the most important gain may be the simple recognition that it is now possible to vote new candidates in – or out.

“Jonathan must go!” shouted one Buhari supporter at the party headquarters, as a crowd danced and sang in celebration on Tuesday night.

“And before he goes, he must return our money,” another woman nearby chimed in.

There was a pause.

“And if anybody tries to steal again, they too must go,” the first supporter said, the faintest note of warning in her voice.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion