- India

- International

Shooting the Indus Waters Treaty won’t solve India’s terror problem

Even if India started on a programme to hold back the Indus waters, the dams needed to do so would take decades to build.

New Delhi: Prime Minister Narendra Modi chairing the meeting on Indus Water Treaty in New Delhi on Monday. (Source: PTI Photo)

New Delhi: Prime Minister Narendra Modi chairing the meeting on Indus Water Treaty in New Delhi on Monday. (Source: PTI Photo)

Five weeks before 26/11, Lashkar-e-Taiba chief Hafiz Muhammad Saeed delivered a speech that, in retrospect, was the manifesto for the carnage soon to unfold in Mumbai. Fields across Punjab, he said, were turning to dust because of Indian “water terrorism”. Hindu India, he went on, was building dams in Kashmir, to choke Pakistan’s water supplies, and cripple its agriculture. For Pakistan, he prophesied, a moment of decision lay ahead: the “crusaders of the east and west have united in a cohesive onslaught against Muslims”.

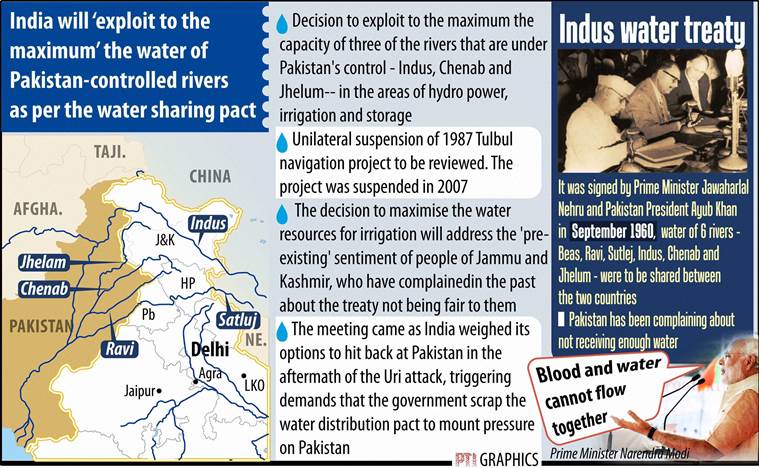

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, on Monday, heard experts weigh in on abrogating the Indus Waters Treaty — the 1960 agreement that governs how India and Pakistan share the five rivers that flow west through the Punjab. Ever since Pakistan’s nuclear weapons deterred India from going to war in 2001-2002, hawks have been arguing that abrogating the treaty would mount unbearable pressure on Pakistan, forcing it to scale back its proxy war.

WATCH: Indus Waters Treaty: India Cannot Unilaterally Separate Itself From Treaty Says Pakistan

Is the plan workable? The simple answer is, no. Legally, abrogating the treaty isn’t workable; strategically, it will demand massive investments for uncertain dividends. Worst of all, it may actually make India’s terror problems worse, not better. From the outset, control of the Indus waters have played a big role in shaping Pakistan’s efforts to seize Kashmir. In his memoirs, Major-General Akbar Khan, the officer who commanded Pakistan’s irregular forces in Kashmir in 1947 noted his country’s “agricultural economy was dependent particularly upon the rivers coming out of Kashmir”. “The Mangla Headworks were actually in Kashmir and the Marala Headworks were within a mile or so of the border. What then would be our position if Kashmir was in Indian hands”?

This still plays on Pakistan’s deepest fears. The day before the Prime Minister’s conference, Saeed held his own meeting on the Indus Treaty with journalists in Lahore. India, he said, was planning to use its dams on the Chenab to flood and choke Pakistan’s lands by turn. Pakistan had to seize Kashmir, he went on to secure its existence. “Potable water will be hard to find within a few years”, he claimed, “there will be no option except war”.

Indian hawks believe disrupting water flows will signal New Delhi’s willingness to impose costs for Pakistan’s use of terror. India, on August 19, 2008, is alleged to have cut the flow of water to Pakistan by 20,000 cubic feet per second, to fill up the Baghliar dam’s reservoir — searing fields across Pakistani Punjab, and provoking Hafiz Saeed’s pre-26/11 speech.

Indus Water Treaty. (Source: PTI GRAPHICS)

Indus Water Treaty. (Source: PTI GRAPHICS)

Even if India started on a programme to hold back the Indus waters, the dams needed to do so would take decades to build. However, India could use its existing storage to disrupt key parts of the agricultural cycle, or impose urban hardship during the leanest summer months. Abrogating the treaty, the hawks’ argument goes, would signal willingness to do so — and thus prompt rethinking in Pakistan’s strategic establishment.

Perhaps this calculation is true — but the fact is events of 2008 enabled the Lashkar to increase its reach and influence in swathes of Punjab. Pakistan’s first response is likely to be step up the heat on India, by escalating its terror offensive, in the hope India will back off. India would be back facing the conundrum it now does — to risk an economy-threatening war, fought under the shadow of nuclear weapons, or doing nothing.

WATCH VIDEO: Sushma Swaraj Hits Out At Pakistan In Her UNGA Address: Analysing Her Speech

The impact on agriculture in 2008, moreover, was nowhere near levels that might cripple Pakistan’s economy. Indian water disruption, thus, would hurt Pakistani agriculture, but its other impact might well be to strengthen jihadist groups.

Finally, it it would be hard to recruit international support against such terrorism: violence carried out retaliate against deliberately-inflicted thirst, for obvious reasons, would carry less moral opprobrium than violence driven by religion.

The end result: India would face heightened terrorism, not less, as a result of abrogating the Treaty. Legally, scrapping the Indus Waters Treaty would also leave India on weak ground. Field Marshal Ayub Khan and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru clearly did not intend for either country to ever exit the treaty unilaterally: there is no clause outlining circumstances under which either India or Pakistan may unilaterally denounce — legalese for exit —the treaty. Instead, the treaty says only that its provisions may only be modified or replaced by “a duly ratified treaty concluded for that purpose between the two Governments”.

In 1969, the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties laid out circumstances in which treaties which do not contain a denunciation clause may be repudiated. Article 56 states that there are just two such get-out-of-jail routes: if it “is established that the parties intended to admit the possibility of denunciation or withdrawal”, or a “right of denunciation or withdrawal may be implied by the nature of the treaty”

Prior to the 1969 treaty, nation-states often resiled on treaties. Faced, in 1798, with bitter trading disputes with France, the United States repudiated a friendship treaty it had signed just two decades earlier; it backed away from an 1827 treaty which gave it and Britain joint rights to the Oregon Territories. But as early as 1944, the United States State Department noted, in a legal advisory, that treaties could only be abrogated with the consent of both parties if there was no provision to do so in the agreement.

India could, of course, act as other big powers have done, and simply ignore the law. The United States mined Cuban harbours, and armed Nicaraguan insurgents, illegally. China recently rejected the verdict of an international court on the South China Seas, rejecting the rules of the International Convention on the Law of the Seas.

This would, however, come at significant costs.

Law scholar Lawrence Helfer notes that the international legal system is “rounded on a fundamental principle: pacta sunt servanda — treaties must be obeyed”. That is the principle India has invoked to argue that Pakistan’s efforts to internationalise the Kashmir dispute are illegal, since it signed the Shimla Agreement, committing it to resolve disputes bilaterally. India used the same principle to insist on the sanctity of the Line of Control in 1999.

For India to act unilaterally on the Indus, thus, would weaken its own case on the big issue — Kashmir. This might be a price worth paying if the dividends were clear, but as the 2008 experience shows us, that’s very far from certain.

Like so many hawkish memes, Indus Treaty abrogation has been marketed as grand strategy. Held up to the light of day, though, it isn’t hard to see it for what it is: an plan that belongs to the dusty shelf reserved for awful ideas.

Apr 24: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05