By Shreerupa Mitra-Jha

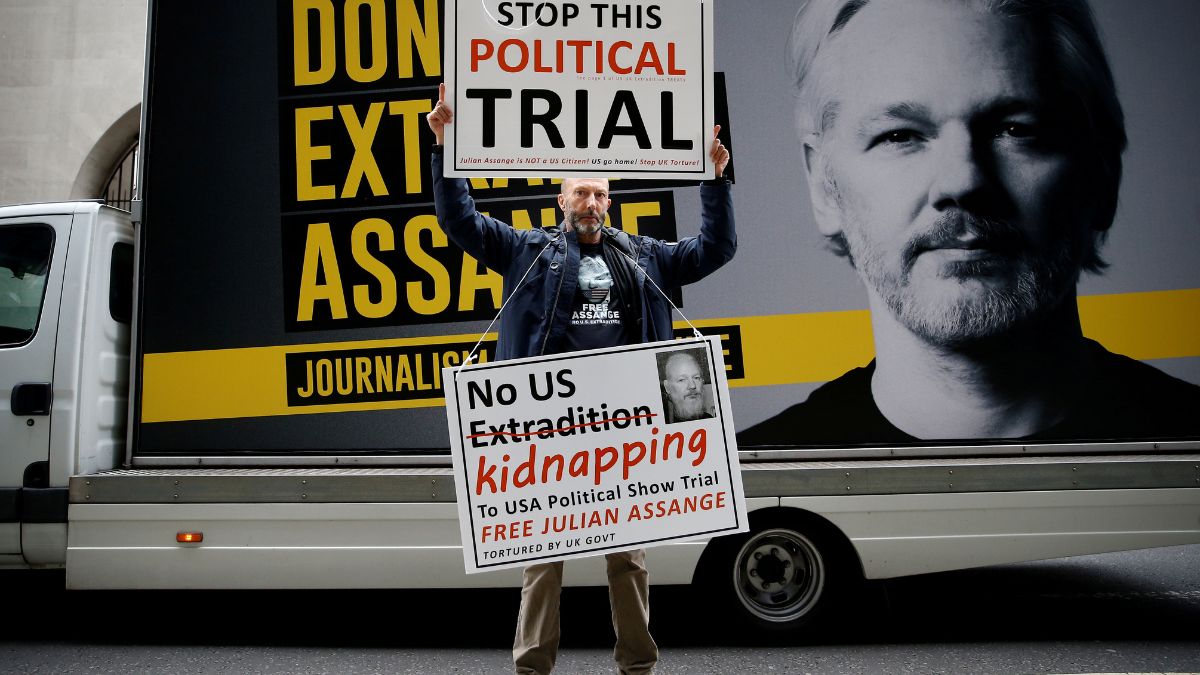

A UN panel on 5 February ruled that WikiLeaks founder, Julian Assange, has been “arbitrarily detained” at the Ecuador Embassy in London and urged the UK and Sweden to ensure his freedom of movement. The panel also ruled that Assange should be accorded an “enforceable right to compensation”.

The Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) had a majority ruling in this case with three of the five members in the panel — one dissented and another recused herself — ruled in favour of the decision. The UK vehemently rejected the ruling that the 44-year-old Australian has been arbitrarily detained and said the UN opinion “changes nothing”. The UK maintains that Assange will be arrested by the Metropolitan Police if he leaves the premises of the Ecuadorean embassy. They also plan to contest the panel’s ruling.

The WGAD — which investigates whether cases of deprivation of liberty imposed arbitrarily are inconsistent with the relevant international standards set forth in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights or in the relevant international legal instruments accepted by the States concerned, particularly the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights and the 1951 Refugee Convention — has handled many high-profile cases in the past like that of the former Maldivian president Mohamed Nasheed and of Iranian-American Washington Post reporter Jason Rezaian.

Although the panel cannot order the release of detainees, its judgment puts moral pressure on the governments involved.

Christophe Peschoux, the chief of the section that deals with working groups at the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, read out the ruling of the WGAD on 5 February to a room packed with journalists at the UN office in Geneva. He spoke to Firstpost on why the panel ruled that Assange’s detention is arbitrary, whether the UN opinion is legally binding on countries, and the rape allegation against Assange, among other issues.

How can the panel term Assange’s lodging at the embassy as ‘arbitrary detention’, if he has stationed himself there of his own free will?

The gist of the matter is that his right to fair trial has been violated by this prolonged situation or this prolonged deprivation of liberty, which arose from the initial investigation that was launched in Sweden, but was never translated into charges — if we are deprived of our freedom, there should be clear charges set by the law. There have never been charges (from the Swedish government). So, effectively he is detained without charges and trial for five years. That’s quite simple in the end.

The difficulty of the case is that he was detained by the British authorities in the British prison in secrecy for 10 days. Then he was detained under house arrest for nearly two years. And since then, he has been detained at the Ecuadorean embassy. In the embassy, he is not detained per se, but he is detained indirectly because if he goes out, he’s going to be arrested. So it’s a new case that pushes the traditional boundaries of the definition of ‘arbitrariness’ a little bit. And that was the subject of heated debate within the working group (WG), and that explains the dissenting view that is more traditional.

But what about the allegation of rape against him in Sweden?

That is something that is outside of the purview of the WG. The decision of the WG has no bearing on these criminal proceedings. If there are allegations of rape, they have to be investigated, they have to be established on factual basis, charges have to be filed, criminal proceedings have to take place. In this case, that did not take place. It’s still at the preliminary investigation stage. What has the (Swedish) prosecutor done in five years? (He is) on very serious charges. It is easy to file charges and then to request Assange be extradited.

The British Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond has called the WGAD judgment on Julian Assange “frankly ridiculous” and has said, “I reject the decision of this working group. It is a group made up of lay people and not lawyers”. What is your comment on such dismissals of UN rulings by member states?

The crux of the matter is the good faith commitment of States to honour their human rights obligations under the treaties that they have ratified — in this case, the UK and Sweden have ratified the International Convention on Civil and Political rights. And it is on this base that the WG made its decision. Now you know the weakness of international law — there is no enforcement mechanism. So implementation relies upon the goodwill of the states and their good faith commitment. If this is not (the case), then because a decision doesn’t coincide with what they see as their interests, they may decide to disregard the decision. But by doing this, they disregard international law and their own obligations, or at least, the interpretation of international law that is made by the WG.

The WG is not made of lawyers but they are internationally recognised experts in their fields. They are coming from five parts of the world. They are acting in full independence. And their deliberations are honest, they are fair and (the decision) is based on all the facts and laws that are known to them. The decision is binding to the extent that the law it is based upon is binding on States. It is also binding because the WG was established by the forerunner of Human Rights Council which was the Human Rights Commission because it could not deal with large amount of complaints it was receiving from people who are deprived of their liberty. So they entrusted the WGs to deal with these cases and to provide authoritative opinions because the WG is a conflict-resolution mechanism — the dissension between the person detained and the detaining authorities. And you, me, any individual detained can file a complaint and have its situation reviewed by the WG. And all States that are members of the (Human Rights) Council have recognised the authority of the WG. When human rights coincide with their (state’s) interests, they abide by human rights, when they don’t, they tend to discredit decisions.

And, in this case, saying that members are not lawyers, that they are “lay people”, I think, is very disrespectful. (It is) very disrespectful towards the WG, because it is shooting the messenger and ignoring the substance of the opinion. If there is dissension, let’s look at the opinion and discuss the merits of the opinion, again, based on facts and law. (It) seems to me that it’s a reasonable approach. And there is an avenue for appeal. If the governments of the UK and Sweden are not happy with the decision — which is understandable and not a surprise; we knew because the WG has received their views — they have two months from the date when they were sent the decision (22 January), to appeal for a review. The WG will look at the new information and if the new information is of such nature that it calls into question their decision, then they will review the decision. It is a very transparent process — the reasoning of the governments is there, the reasoning of Assange’s lawyers is there, and the deliberations are on record in the 18 pages (of the report).

The UK has said that it is not a signatory to the Caracas Convention and, therefore, under no legal obligation to recognise the ‘diplomatic asylum’ provided by Ecuadorean government to Assange. Do you have any comments on that?

International law is above domestic or regional law in the accepted hierarchy of norms of the world we live in. The WG did not pronounce itself on the question of asylum seeking, but my view as a human rights officer is that the UK and Sweden may not have ratified that regional convention, but clearly they have ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention on the status of refugees that provides for non-refoulement of individuals who express fear for persecution if they were to be refouled to their country of origin or another country. And this is binding, which is the respect of the Right of Asylum, which is a very important safeguard in today’s world, and (which) should be respected. Any of us can become refugees at any time these days. And if this mechanism is going to (be) questioned and is not protected by States, then it is weakened and may disappear.

You said earlier today that the decision of the WG panel was adopted by majority rulings not by consensus which is unusual for the WGAD. Why is it unusual?

The working methods of the WG provide that cases have to be decided by simple majority — so three or four out of five. But successive chairpersons of the WG, to get the strongest possible decisions, have sought consensus. There is a tacit agreement in the WG that it is better to have consensus than decision by majority ruling. And most of the decisions are made on the basis of consensus. In the past, there have been a number of cases where decisions have been made by a majority rule of four or three members. The newness in the case of Assange is that the WG decided to make it (the dissenting view) public out of transparency, and deference and respect for the dissenting view. The appended it to the decision. So that’s the new element — the publication of the dissenting view.

To date, the WGAD has adopted more than 1,000 opinions covering more than 130 countries. How many of those opinions and recommendations have been actually implemented by the States?

We don’t have complete statistics. We look at the number of cases of which we are aware — the individuals who have been released. Last year, 12 individuals who were subjects of opinions were released. Last year, the WG’s number of opinions were 55 or 56. Some of the 12 were also subjects of earlier opinions of 2014. Recent cases have involved the former deposed president of the Maldives, Nasheed. He was the subject of an opinion. The opinion found that his detention was arbitrary, the government appealed against the decision, the appeal was declined and in the end, he was released. That’s a famous case.

Another case was when the WG contributed to the release of the American journalist who was held in Iran. And the WG was part of the negotiations. So these are well-known cases, but the point I want to make is that although these cases seem to indicate that the WG is dealing with high-profile cases, the vast majority of the cases deals with ordinary folks, like you and me who may be detained in a district jail, who wake up without any recourse. They are in the hands of the detaining authority. It is a very precious mechanism that should be cherished and protected and strengthened.

The author is a journalist at the United Nations Office in Geneva

)

)

)

)

)

)

)