The US is simmering and bubbling, divided by economics, race and resentment. Go to any US city and you will see this. I went to Cleveland, where the GOP nominated Donald Trump, and I saw a working-class white neighborhood, Parma, Ohio, embracing Trump – and a poor black neighborhood, Central, outraged at Trump.

I also saw two neighborhoods which, despite their racial difference, share a sense of frustration at being left behind.

The African American residents of Central, filled with projects, have long been excluded, yet they feel the Democrats are championing their frustrations. For the white working class in Parma, being towards the bottom is a newer feeling. But more importantly, they feel disrespected, with nobody listening to their concerns.

Until Trump arrived.

Parma, 20 miles away from downtown, is defined by auto factories: massive edifices to another era that now sit mostly idle. Scattered throughout are union halls, like UAW Local 1005, which is mostly empty, holding only a few cars. A few hundred yards down the street is a General Motors factory. Its parking lot is only a fifth full. Surrounding the factories is street after street of well-kept small tract homes.

Parma is lower income to middle income, and almost all white. It has suffered over the last decades as the auto factories have declined, and other factories have closed up and moved on.

The union halls, the factories, all used to define the neighborhood, filling it with pride. You can still find some union members, but most of them are retired. George Navrek, 79, is one of those, a lifelong member of UAW local 91, and a Hillary voter. He and his buddies meet each afternoon at the local McDonald’s, “remembering good times”. He is still proud: “I am a union man, through and through. They made this country, they gave us our standard of living.”

That, however, is the past; the present can be found in any local bar, like Erin’s Pub a mile away. It is a small and sweet Irish bar, although most of the regulars are a mix of third generation Polish, German, Italian, Irish and other Europeans. It has a few retired union workers as regulars, but mostly it is younger non-union guys, all who have made or make their living working with their hands.

Like all neighborhood bars, it has the feel of a clubhouse, one that is now tilting towards Trump. There are Hillary supporters among the regulars, yet they are outnumbered, certainly in intensity.

Every Trump supporter who spoke to me was gracious and eager to explain why he or she liked Trump, why Trump was not a racist, and why they themselves were not racist.

Joe Kuzema, 41, owns his own security company. “Country is falling apart, from the bottom up. We got these lazy people freeloading off the government. Meanwhile the rich just keep getting richer, and working guys are getting screwed. We just got to break the system.”

When it came to race, he jumps to explain: “My ex-wife is black. I have hired plenty of blacks to work for me. I am not a racist. Trump is not the racist. Hillary is the racist, only standing up for women and blacks.”

Others are far more cautious, aware of the obvious elephant in the room. One of the owners of Erin’s Pub is Donald Weichsel, 67, a retired union firefighter and army veteran, is unsure of how he will vote. He voted for McCain in 2008 and Obama in 2012. He sits quietly, and thinks. “I am just disgusted with everything. Hillary is dishonest and Trump is a loose cannon.”

I ask him if Trump is a racist, and he turns pained. “I want to chose my words carefully. He isn’t a racist, but a realist. It is easy for folks who live in wealthy neighborhoods to say they will accept any neighbor of any color. Who wouldn’t want to have a doctor or lawyer move next door, regardless of if they are black or white? But that isn’t who is moving into our neighborhood. It is mostly people without jobs, on assistance, and mostly African Americans from the projects, and it is sending our crime higher and our house prices lower. I think folks in rich neighborhoods wouldn’t want that either.”

Most others, especially the Trump supporters, are unabashed in their views, celebratory, giddy to have someone addressing their concerns, and talking their language. Two guys, just off work, come in and yell to their friends, “Fuck yeah, dicks! The Polacks for Trump are here!”

That everyone else hates Trump makes them all the more confidant he is their man, further cements the feeling they are, finally, members of an exclusive club. As one guy yelled when the TV showed a controversy over something Trump said: “You get them Donald! They been getting us forever.”

Most of all, Trump voters want respect. They want respect for their long hours of work that risks their bodies, for the hands caught in vices, backs wrenched by weights, and knees torn. They want respect because they are doing dangerous work, but their pay has been flat for decades.

They want respect because they haven’t just lost economically, but also socially. When they turn on the TV, they see their way of life being mocked and made fun of as nothing but uneducated white trash.

With Trump, they are finding someone who gives them respect. He talks their language, addresses their concerns. Sometimes it is celebrating what defines their neighborhood, what they in Parma have in common: being white. They and Trump are playing in dangerous territory, with the need for respect tipping into misplaced revenge.

In another all-white working-class neighborhood not far away, a collection of retired workers, all Trump voters, gather in the mornings at McDonald’s. When the talk turned to politics the N-word is thrown around with ease, and racial jokes are par for the course.

The need for respect, the feeling of being left behind, is well-understood 15 miles away in the all-black neighborhood of Central. If Parma is like a factory town losing its factories, Central is a town that hasn’t had them for decades.

It is has long been poor, about three times poorer than Parma. It is filled with low-income projects, their version of Parma’s tract homes, and run-down shops – dollar stores, convenience stores, hair shops and payday loans with employees behind thick Plexiglas. The oldest housing project is the Outhwaite Homes; a sprawling regimented 10-block complex of two- and three-storey low rises.

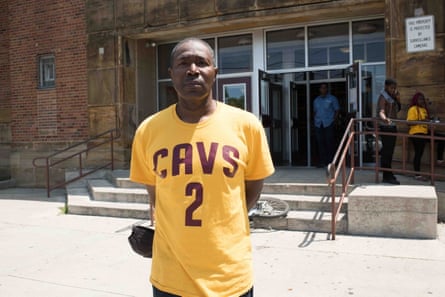

A few blocks from the projects, Rick L Pittman, 53, sits in the McDonald’s. He often comes here to meet his friend, study, or write poetry. He grew up in the projects, focused on running, and got a scholarship to a far away college. He came back to teach in Cleveland, before dedicating himself to politics (he ran for mayor in 2002) and writing.

He has spent his life trying to understand the projects, understand the violence and the poverty. He has seen things get better, but life in Central is still about poverty and violence, and a code of respect. “I got a gun put to my head at 13 for just walking the wrong way. That is the problem with the projects, when you don’t have anything, respect is all you have.”

Those living in Central haven’t had anything but their pride for a long time. It has long been one of the poorest neighborhoods in the country, a place sociologist have studied and labeled as concentrated poverty. It has also been constantly demeaned, a place everyone else just calls the slum, or the ghetto, and the residents hoodlums, thugs or worse.

What I heard in Central, despite the hardships and frustrations, was less anger and more resignation. Partly that was because this has been happening for a long time, but mostly because people feel they do have a political voice. They believe the Democrats are working for them, they might not like everything about the party, they might not fully like the results, but the party is respecting their concerns.

It meant that the overwhelming political concern I heard had little to do with anything other than electing Hillary, and stopping Trump.

Marvalene Ford, 61: “I am for Hillary. Trump is a racist. It is just amazing we still got to deal with all of this.”

James, 51, “Trump? That man is a racist. But the world is racist. Look around you. See any whites here? I give Trump this much, he is exposing what everyone already knows.”

King Dallas, 37: “Racism will always be there, but to be really dangerous it needs a leader. Trump is that leader.”

Both the black and white working class are stagnating, falling further behind – almost anyone except the very wealthy are, regardless of race. It is humiliating, and many have responded with a want for respect. That they are both doing it along racial lines, rather than working together, isn’t fully surprising: we are largely a segregated country.

Yet only African Americans have a long history of racial oppression. Consequently, how they respond is filled with difference. In Central they can tell me without pause that they voted for Obama because he was black, and they won’t vote for Trump because he doesn’t like African Americans.

For the working class whites, given our country’s history of racism, of segregation, of slavery, finding respect through race is dangerous territory. Yet, with the unions mostly gone, with so many other outlets for respect eroded, it has left many with few easy options other than surging ahead, led by Trump, into the ugly, unacceptable territory of outright racism.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion