When Meth Was an Antidepressant

It’s hard to tell which drugs are dangerous and which are revolutionary.

Acting Drug Enforcement Administration chief Chuck Rosenberg is in hot box water after calling medical marijuana a “joke.”

“What really bothers me is the notion that marijuana is also medicinal—because it’s not,” Rosenberg said in a briefing to reporters earlier this month. “We can have an intellectually honest debate about whether we should legalize something that is bad and dangerous, but don’t call it medicine—that is a joke.”

That’s not an uncommon view among the tough-on-drugs crowd. But, in the age of hemp-oil seizure medication, it’s not exactly a tactful thing to say. Now, a bipartisan group of seven lawmakers is calling for Rosenberg’s firing.

Rosenberg’s comments are “indicative of a throwback ideology rooted in a failed War on Drugs,” the letter, spearheaded by Earl Blumenauer, a Democratic representative from Oregon, reads. “They do not reflect the overwhelming body of testimonial evidence, reforms happening across the country at the state level and in Congress, or the opinion of the American people.”

You may not agree with Rosenberg, but you have to admit: The distinction between medication and recreation is blurry, and becoming increasingly so.

This has always been a tough call for regulators to make. Take meth, for example. It’s the worst drug you can take, right? An overdose can cause convulsions or death. In many states taking it during pregnancy can get you arrested for child abuse.

But between the 1930s and 1950s, meth was a top-line antidepressant.

In 1929, a Los Angeles chemist named Gordon Alles found that amphetamines could induce a feeling of euphoria, as the magazine Chemical Heritage describes:

On June 3, 1929, a doctor injected 50 milligrams of amphetamine into Alles’s body … Seven minutes later he sniffed: his nose was dry and clear. His blood pressure climbed dramatically. After 17 minutes he noted heart palpitations but also a “feeling of well being.” He grew chatty and at a dinner party that night considered himself unusually witty. Some eight hours after taking the drug his blood pressure had nearly returned to normal.

Alles quickly patented his discovery, and the rest is a history of use—“for mild depression”—and abuse. Meth is thought to have fueled the Nazis’ blitzkriegs during World War II. The Allies used it, too, for “fighting spirit.”

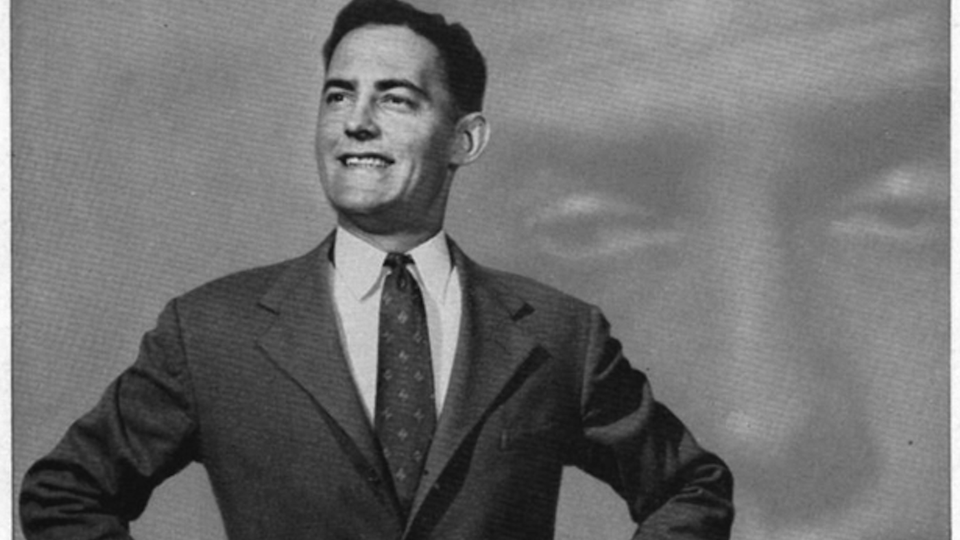

By 1945, half a million everyday Americans were taking meth-like tablets either for mood or weight loss. President John F. Kennedy was routinely injected with 15 mg of methamphetamine by his personal physician in order to maintain his sprightly appearance.

As the potential for abuse and dependence gradually became clear, the FDA cracked down, and meth production moved into underground labs.

How is meth different from modern amphetamines, such as Adderall? There isn’t much of a difference, according to the Columbia University psychiatry professor Carl Hart.

“It’s the exact same drug, the only difference is that methamphetamine has a methyl group attached to it,” he said in an interview with MSNBC’s Chris Hayes recently. “Adderall, compared to methamphetamine, has very similar effects.”

This does not, of course, mean that meth and amphetamines aren’t harmful—they obviously are, especially at high doses. (And marijuana is almost certainly less harmful than other drugs, including alcohol.) But it’s an example of how pharmaceuticals, at their core, are drugs. They’re chemicals that were mixed together and believed to be beneficial to humanity, until they weren’t.

Prescription painkillers have gone from lauded to reviled ever since the opioid epidemic began killing thousands of Americans. Medical marijuana is making the reverse trek—moving from DARE class villain to unconventional treatment for autistic children. But when it comes to deciding whether drugs are cures or killers, it can be hard to know where to draw the line. At least without the hindsight of history.