The intelligent soldier system - military wearables

Jul 23, 2015

On May 19th 2015, IDTechEx attended a conference aboard HMS Belfast in London, bringing together senior military innovation personnel with acting servicemen and technical innovators in relevant fields. The topic for discussion was wearable technology for the military. The day began by outlining the needs of the dismounted soldier in active service, and the conversation continued to describe the nature of the problems, potential solutions, and crucially, a description of the process used to achieve these improvements.

The following sections outline some of the key messages that were echoed throughout the sessions:

'Improving the capabilities of the soldier is the primary aim. Any technology will only ever be part of the potential solutions.'

Military development programs are revolved around improving the capabilities of the soldier. Technology platforms, whether they are wearable or not, and regardless of technical sophistication, will only ever be a part of the solution in this development process.

All of the military personnel at the event agreed that too much of the development so far has been technology focussed, without properly addressing the needs of the soldier. This is an expected problem for a small company looking to exploit new markets for their technology. At the other end of the spectrum, the likes of BAE Systems ,Lockheed Martin and others are involving military personnel earlier in the development process, but the challenge is significant, because the stakes are at their highest.

If problems exist with consumer wearable devices being left behind, then this is only augmented when it comes to military platforms. WO1 Gary Simpson of the parachute regiment clearly illustrated this. He repeated a need to enhance the "situational awareness" for soldiers on the ground. However, with a 57kg of weight to carry during operation, anything which is considered non-essential to an operation will simply be "left under the bed".

The problem with traditional development processes, and a vision of the future

"We need to get away from the Christmas tree approach when integrating new technologies". This is the process of simply adding new equipment on top of the existing soldier platform, adding complexity, confusion and weight.

James Gerard from BAE Systems spoke of recent steps they have taken to get away from this approach. By way of example, he described the development of warships. For over 100 years, the approach would be almost entirely additive - whether it be a bigger gun, better radar reflectors, torpedo resistant hull, and so on. By way of showing their move away from this, he described the Type 45 Destroyer, which involved a redesign with integration and functional optimisation at it's heart.

For the dismounted soldier, the solution needs focus on two key areas:

Adaptability describes a modular approach to the system, where different components can be selected depending on the mission or even personal preference. This requires connector standards and design integration between previously separate areas of equipment development.

Practicality is based around the soldier's needs. An average platoon carries 16 different kinds of battery, with a single soldier requiring 5/6 different types. The lack of integration also extends to data connectors, wireless protocols and equipment examples. This presents a logistical challenge to the majority of national military organisations, and needs to be understood by developers if they are to contribute positively to continued platform development.

Key technology trends beneath the surface

When it comes to technology integration, the military has a very mixed track record. At one end, huge investments are driving significant advances in weaponry, communications, armour, vehicles, right through to exoskeletons and battlefield medicine. The same is true of wearable technology, but the additional human factors around soldier preference and weight severely limit the functionalities that can be employed.

So what is in place? Hand-held GPS, optical sights for weaponry, thermal or night vision imaging in headsets and radio-based communications are common. These technologies have been employed for decades, with the military often adopting these techniques some time before commercial equivalents appeared.

Beneath the surface, key technologies are enabling step change in many aspects of the soldier system. Examples given during the conference included 3D printing helmet linings greatly improves temperature control in hot environments, on-body printed antennas with minimal visible signature, IR shielding techniques used to minimise infantry heat signatures and conductive textiles for seamless integration of electronic components into uniform.

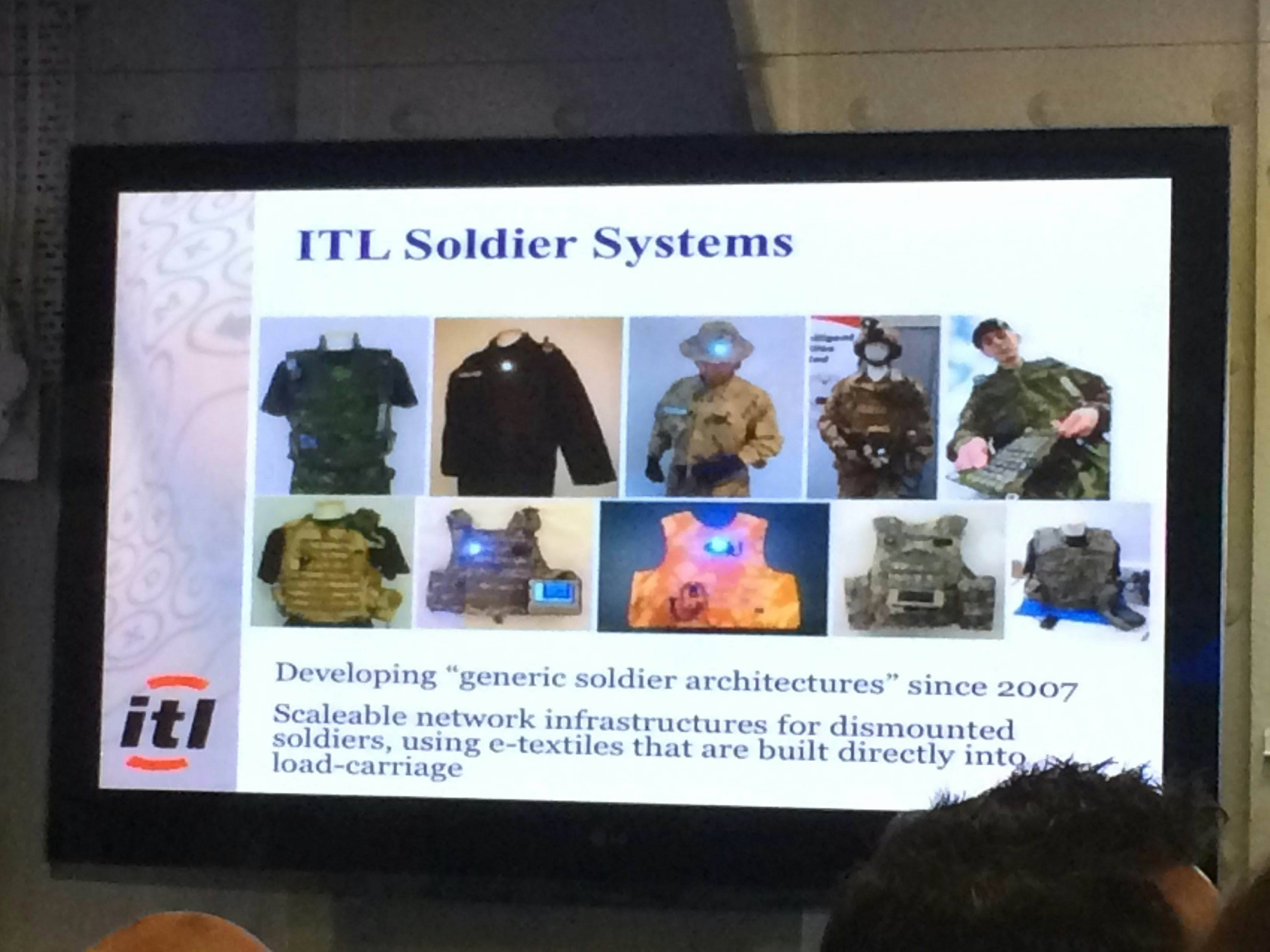

Intelligent Textiles Limited's Soldier system platforms

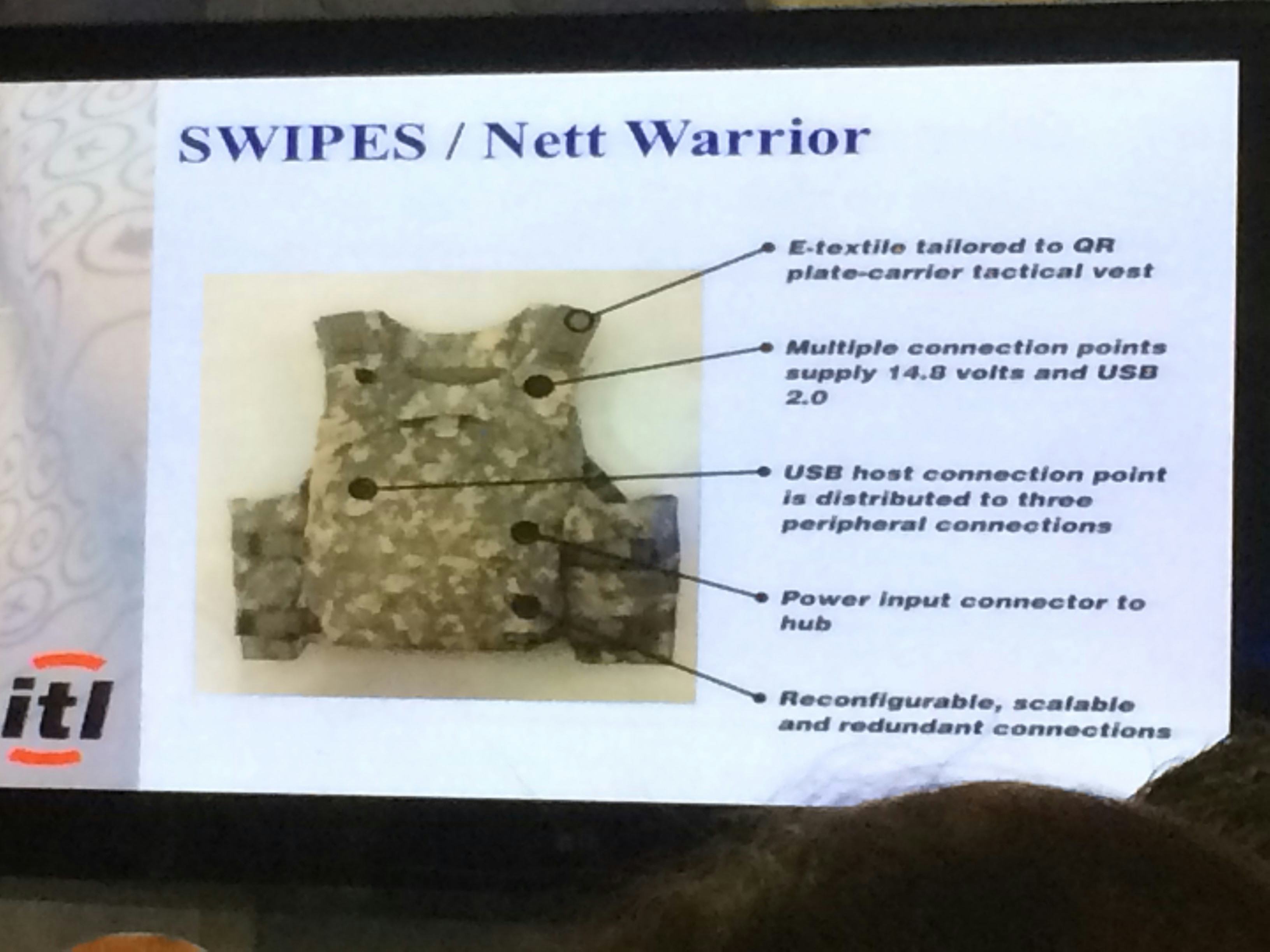

An example project from Intelligent Textiles Limited

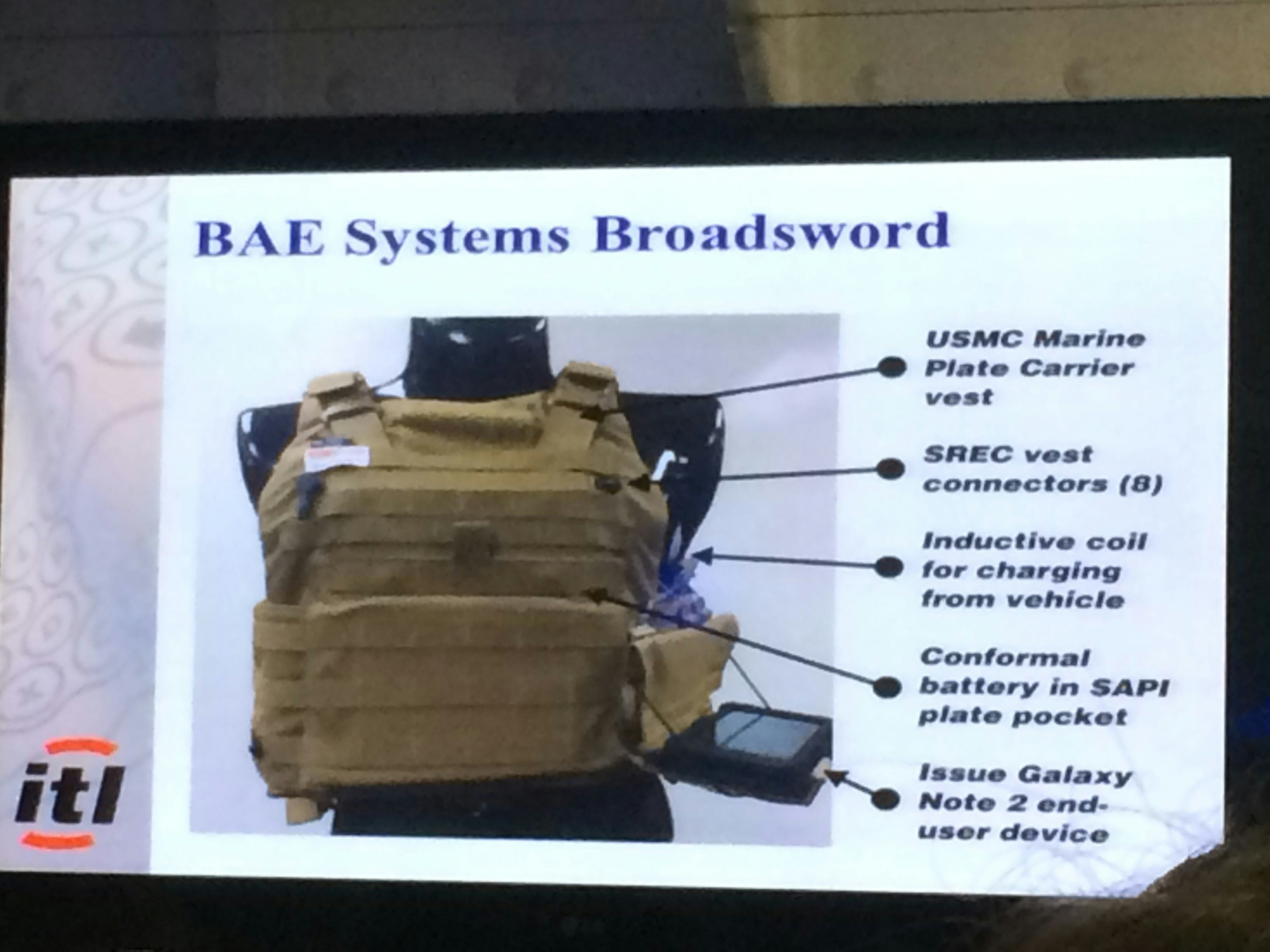

An example project from Intelligent Textiles Limited, with BAE Systems

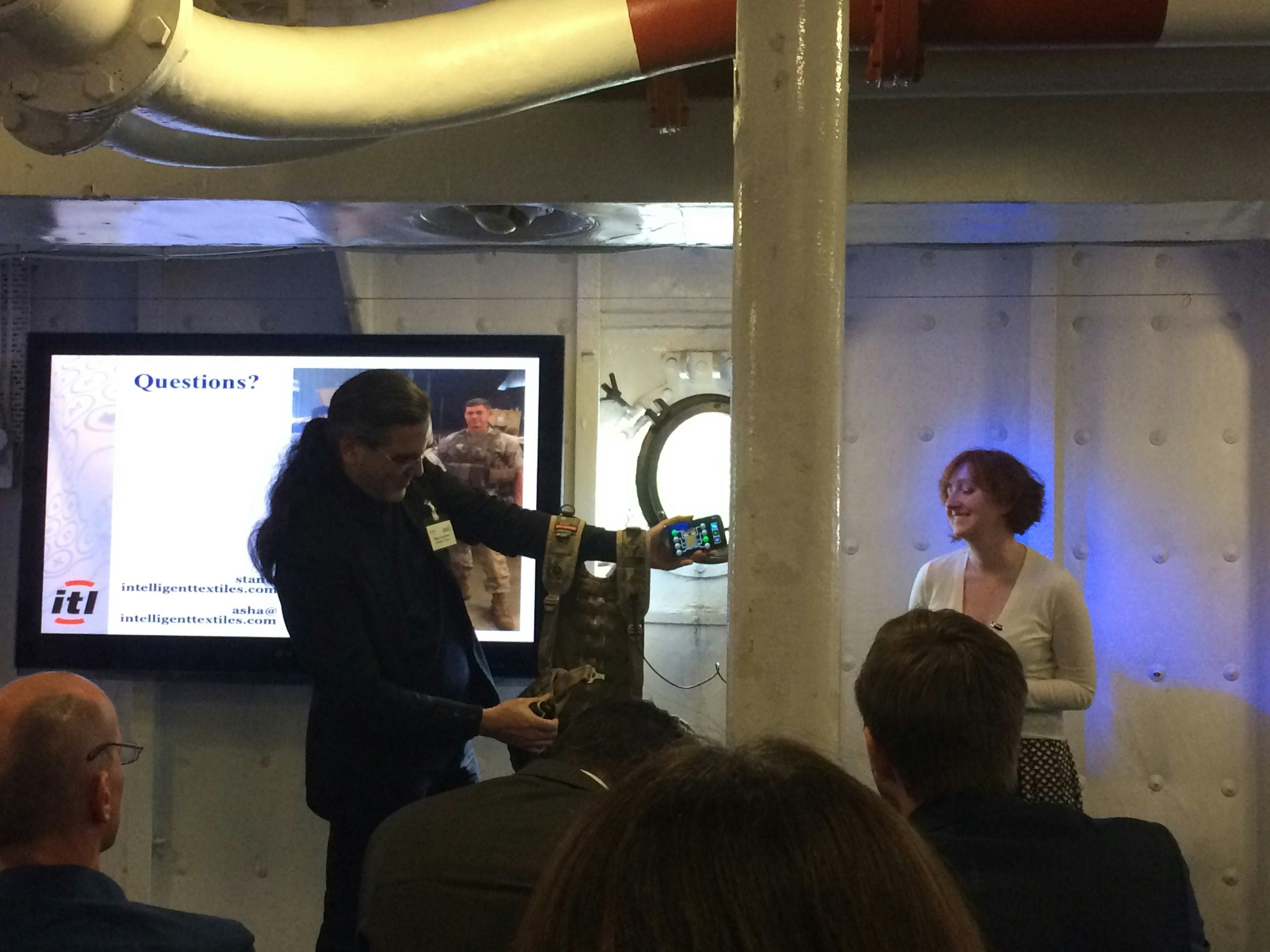

The co-founders of Intelligent Textiles Limited show their demonstrator product

The most essential message for developers on the technology side is the increasing need for integration of systems. Having multiple battery types, excessive cabling, and incompatible systems are all very avoidable problems. The integration of power and data systems into clothing, and particularly body armour is seen as the next key development for many global military forces. This will provide a weight-efficient, customisable and practical platform for technology integration, enabling the potential of new emerging components to be realised.

But some component types are missing

One of the key components that seemed to be missing throughout this discussion was sensors. Whilst many types of optical or EM sensors are used to sense the environment around the soldier, there are no systems in place to directly sense vital signs of the soldier.

Sergeant Duncan Stewart and Major Richard Cave all stated clearly that live monitoring of soldier vital signs during combat would be actively detrimental to the role of the army. Both legal and ethical accountability issues arise, and whilst the data could be useful in a retrospective analysis, they do not see live data monitoring during service as useful at all.

However, this is not to say that vital signs monitoring has no place in the military. On the contrary, just one day before the event, I interviewed Pierre-Alexandre Fournier, CEO and co-founder of Hexoskin, a smart clothing company which can do vital signs monitoring. They have had close relationships with several partners in the military space, around monitoring the vital signs of the soldier to analyse, assess and optimise physical conditioning to ensure combat readiness. In summary, vital signs monitoring is great for training and post-event analysis, but not for live monitoring.

The human factor of wearable technology means that developers truly need to understand the needs of the user. In military applications, this need equates to life-or-death situations. Developers must truly understand the system that they are contributing to in order to make a positive impact.

Military applications covered at IDTechEx Wearable USA

In recognition the opportunity for wearable technology in the military, IDTechEx are constructing a specialist track on this topic at IDTechEx Wearable USA, held on November 18-19 in Santa Clara, California. To find out more about the event, or to apply for a speaking slot, or to find out more about exhibition opportunities, please email j.hayward@idtechex.com