The confessional memoir is disreputable. Critics tend to dismiss it as the equivalent of a selfie, a look-at-me snapshot, a glorified ego trip. Narcissism, they say, is inscribed in the very word “memoir”: me-moi. But the genre has a long history: Ovid’s Amores; St Augustine, Rousseau and De Quincey; the American poets (Robert Lowell, Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, WD Snodgrass, John Berryman) who came to prominence in the 1950s and 60s. And there has been no let-up over the past two decades.

The shelves above my desk offer the following random sample. Kathryn Harrison’s The Kiss, which recounts her incestuous relationship with her father. Rachel Cusk’s Aftermath, recalling the break-up of a marriage. Julie Myerson’s The Lost Child, about her son’s problems with skunk. James Lasdun’s Give Me Everything You Have, which documents the ordeal of being stalked by a mentally unstable former student. Mary Loudon’s Relative Stranger, which pieces together the life of her sister, who, estranged from the family, lived under a new identity as a man. Julia Blackburn’s The Three of Us, which tells how, as a teenager, she became the lover of her mother’s lover, who was their lodger. Not to mention titles by Jeanette Winterson, Dave Eggers, Lorna Sage, AM Homes, Jackie Kay, Tobias Wolff and the current doyen of life writing, Karl Ove Knausgaard, all of whom have contributed significantly to the genre.

These books do more than lift the lid, spill the beans, rattle skeletons in the closet, and so on. Still, as those mostly pejorative metaphors imply, exposure of some kind is expected, perhaps of a messy or even sleazy kind – the equivalent of Tracey Emin’s tent (with the names of all her lovers) or bed (with the detritus of her private life spilled across). What confessional memoirs have in common is an intimacy we don’t normally expect – the reader is given privileged access to truths the author feels impelled to disclose, awkward or painful though they might be. Mortality is often at the heart of it: the life-writing turns out to mean death-writing. But sexual transgression, madness, deceit, crime, addiction and all manner of deadly sins are involved too.

Why the impulse to ’fess up? In his essay “Why I Write” (1946) George Orwell gave four reasons for writing: aesthetic enthusiasm, historical impulse, political purpose and, topping the list, “sheer egoism”, which he defined as the “desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on grown-ups who snubbed you in childhood, etc”. With confessional memoirs, you could say there are seven possible motives. To begin with the least convincing:

Spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings (Wordsworth) or free association (Freud)

I couldn’t help it, it just came out of me, unexpurgated, because the experiences I had were so immense there was no choice.

Unfortunately, this theory doesn’t accord with the process of writing. Emotion on the page is always manufactured: retrospective, artful, a declaration of the author’s heart but with calculated designs on the reader’s. In conversation or on chatshows, people do come out with unscripted remarks. But everything we write is filtered, even diary entries, and words intended for publication are filtered several times. So it can be helped. Published confessions are never involuntary.

An opposite, more plausible but overly cynical theory is:

Confession as an apologia or self-justification, a strategic bid for sympathy and admiration

Owning up to problems, faults and misdeeds as a way to win friends. Show your achilles heel and, rather than shoot a poisoned arrow at it, the reader will feel protective and on your side.

Confessional literature always involves strategy – a judgment about what the impact on the reader will be, even if that judgment sometimes proves to be a misjudgment. When Myerson wrote her memoir about her son, she hoped that people would understand it as an attempt to make the dangers of teenage cannabis addiction more visible, not that she would be vilified for writing the book. It is always a matter of calculation. Vulnerable, derogatory or mildly deprecating self-presentation is sometimes part of that calculation. Goody-goody narrators rarely win our sympathy: they are too perfect to be true, too perfect to be likable. Blank narrators aren’t likable either. Better to say “I’m bad” and hope the reader responds “No, not bad, just human”.

Confession as a desire to shock – the memoir as a screaming tabloid headline

Books have to make their way in the world, and to be noticed it helps if the story is sensational. Or, if it isn’t sensational, to make it so, by spicing it up, exaggerating, even inventing.

When James Frey wrote his A Million Little Pieces, he thought that it would make for a more dramatic story to say that he spent 87 days in a prison cell for causing a violent melee while high on crack, rather than that he had been held at a police station for a few hours for a series of minor offences. As his case shows, though, the shocking facts had better not be shocking fictions, or you risk being rumbled.

Sometimes the facts are shocking, without any embroidery. Thomas Blackburn’s memoir A Clip of Steel takes its title from the mechanical device sent to him at boarding school by his father, in order to discourage involuntary ejaculation and masturbation: “the instrument had an outer clip of thin firm steel whose inner edge was serrated with spiked teeth … if you had an erection then your expanding penis pressed into the sharp teeth of the firm outer clip.” It is sometimes said that today’s memoirs keep upping the ante, with misery piled on misery, and explicitness reaching new levels. But Blackburn’s book came out nearly half a century ago, as did JR Ackerley’s two memoirs My Dog Tulip and My Father and Myself, which aren’t only frank about his homosexuality but describe canine love (his sensual arousal when touching his pet alsatian) in astonishing physical detail.

Confession as the desire to redefine what is shocking; to nail the hypocrisy and shallowness of polite society

Many a memoir composed by a writer in one generation sets out to expose the lies and secrets of a previous generation, on the grounds that those lies and secrets – about illegitimacy, say, or mental illness – are no longer a source of shame, but “normal”, acceptable, and worth attending to rather than hiding away. When I showed the draft of a memoir I had written about my father to my mother, one of the few things she asked me to remove was a reference to her being a Catholic. I did as she asked but went on to write a book about her that explored the backdrop to her request. Disguising her Catholicism, playing down the size of her family (she was the 19th of 20 children), giving herself a new name and in effect renouncing her Irishness were choices she had made in order to be assimilated into English society. She felt (or was made to feel) awkward about her background, whereas for me there was no shame attached – rather the opposite, in fact.

The drama of the ego. Confession as performance and showmanship, its natural arena not a secret cloister but a soapbox or a stage

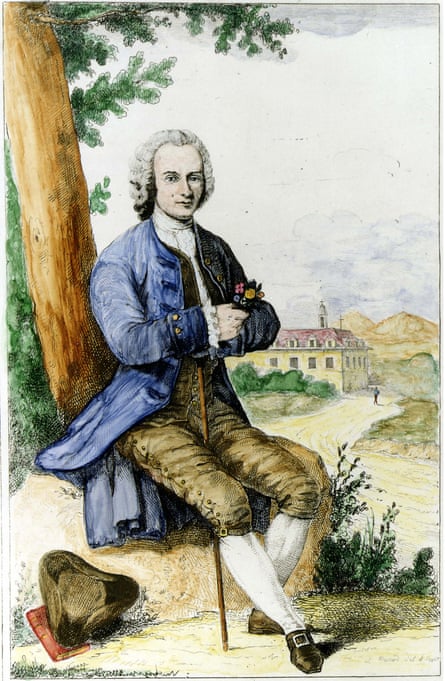

The confessional writer issues a challenge: “Look at what I’ve done, felt and thought, and judge me if you dare.” Rousseau begins his Confessions by emphasising his honesty and plain dealing: his intention is to paint “a portrait in every way true to nature”, one that will “bare my secret soul”. But the metaphor quickly shifts from realistic portraiture to theatre: “Let the numberless legion of my fellow men gather round me and hear my confessions. Let them groan at my depravities, and blush for my misdeeds. But let each one of them reveal his heart at the foot of Thy throne with equal sincerity, and may any man who dares say ‘I was a better man than he’.” Acutely aware of his audience, Rousseau is determined to put on a show. And what a show it is. He steals, he tells lies, he sends his children to an orphanage, and that’s not even to mention his sexual transgressions – masturbation, flashing, sadomasochism, a visit to a brothel, deep frustration when he fails to perform for a beautiful courtesan because she has a malformed nipple, taking turns to have sex with a young girl. Rousseau relishes unburdening himself – and being watched: “I must remain incessantly beneath [the reader’s] gaze, so that he may follow me in all the extravagances of my heart and into every least corner of my life.” Self-dramatisation is integral to the genre.

The confessional memoir as a piece of truth-telling – its primary impulse being to set the record straight, to bear witness

And to be reliable: the narrator’s truth may be subjective but the reader wants to believe that he or she is honest. Good journalism works like this too, reporting from the frontline or recounting first-hand, from personal experience, what it is like to be in a war, say, or a prison, or, in the case of Primo Levi and other Holocaust survivors, a concentration camp. We don’t tend to attach the word “confessional” to this kind of memoir, when the subject is world history, rather than family history. But the intimacy of the witnessing often is confessional, and that is what sets it apart. There is a wonderful example of witness-bearing in Orwell’s essay “A Hanging”, about his experience of watching a man being hanged in Burma; there are details in it so idiosyncratic they seem to guarantee its authenticity: a dog bounding around and destroying the solemnity of the occasion; the condemned man carefully stepping aside to avoid a puddle even though he knows he is about to die; the relief and gallows humour among the assembled guards once he is dead. Few of us are witness to such dramatic events. But even with our smaller experiences, truth-telling is part of the contract – indeed the main clause – and woe to those (such as Frey or Binjamin Wilkomirski in Fragments: Memories of a Wartime Childhood) who betray that trust.

Finally, the principal yet most contentious motive:

Confession as catharsis, cleansing, or purgation

Something bad has happened, and putting it in writing, or putting it out there in the world, is a way of feeling better about it.

“Give sorrow words,” Shakespeare said, “the grief that does not speak / Whispers the o’er fraught heart and bids it break.” Get it on paper. Set it down in words. Writing as therapy.

Ah, therapy – a word generally held to be suspect when associated with literature. The novelist Bernice Rubens said, “You should always write in yesterday’s blood”, reinforcing the idea that what is therapeutic can’t ever be literature, which has to be considered and retrospective. But the therapeutic impulse needn’t always be damaging. Rousseau said that he wrote to ease his conscience, and Virginia Woolf described how writing could “blunt the sledge-hammer force” of childhood trauma: “It is only by putting it into words that I make it whole; this wholeness means that it has lost its power to hurt me.”

You can write to heal a wound and yet be detached. Ackerley talks of trying to see his life as if it were someone else’s he is “prowling about in”. And there is a line on the first page of Susan Sontag’s novel Death Kit that voices a similar sentiment: “Some people are their lives,” she says, others “merely inhabit” them. A degree of watchfulness is essential: a capacity to stand outside oneself, or float above. There is a brilliant example in the poem “First” by Sharon Olds, where she recalls giving a blow job in a steam bath to a much older man and turns his abusive taunt – “You’ve been sucking cock since you were 14” – into a compliment, an “unmeant gift”. Rather than feeling soiled by his insult, she rises above it, cleansed and empowered.

“TMI,” people say: “I don’t wish to know that.” And it is true that some revelations make us feel uncomfortable, as though voyeuristic or complicit. Confessional literature rests on a premise of recognition or equivalence, but if there is none, if we feel, ugh, no way, then the mission fails. The author stretches out a hand but the reader refuses to take it.

When private matters are made public, there will always be protests: leave it out! But there will also be readers who feel consoled and affirmed, grateful for the risky stuff left in. Poetry and fiction may command more respect. But if literature is the enemy of discretion and conformity, if its value lies in breaking the rules by means of truth-telling, then confessional memoirs may be the truest literature of all.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion