Savvy shoppers can spot the difference between clothes from Gap Inc., Ralph Lauren Corp. and Abercrombie & Fitch Co. right away. But according to the stock market, they’re all the same—and equally unattractive. Their share prices have fallen 30% or more this year as these onetime trendsetters struggle to find their place in a new retailing environment. Fast fashion is now king, and stores such as H&M and Zara rule shopping districts and malls worldwide, leaving investors with a tough choice: Do you chase the trendy stocks or bet that the unfashionable laggards will make a comeback?

Fast fashion is not exactly new, but the retailing strategy of delivering stylish clothes fast and cheap, with fresh items arriving at store racks continuously to create a wonderfully diverse selection, has become one of the great business disruption stories.

“It’s here to stay,” says George Minakakis, a retail consultant and chief executive of Inception Retail Group, in Toronto.

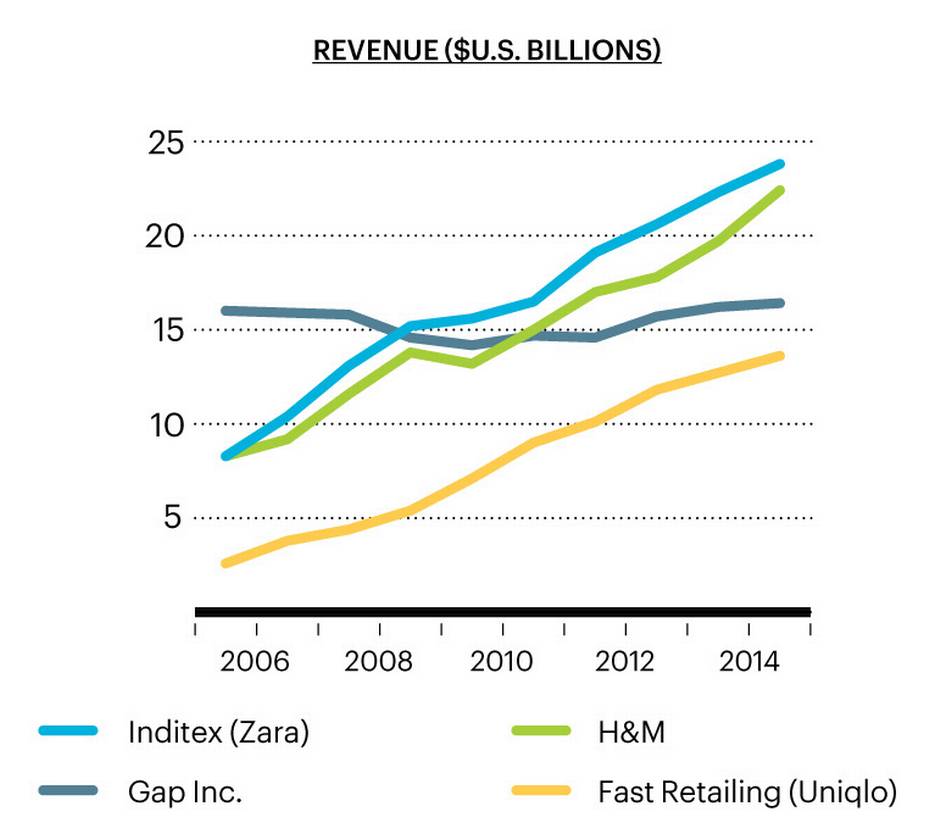

That explains why the old guard is shrinking as fast fashion continues to grow. Hennes & Mauritz AB, the Swedish parent of H&M, has been expanding at a blistering clip, and it has collaborated with top designers such as Stella McCartney, Versace and Alexander Wang. The company now operates 3,700 stores globally, up more than 1,000 in the past three years, and it has plans to open another 240 stores in the fourth quarter, making it the world’s second-largest clothing retailer.

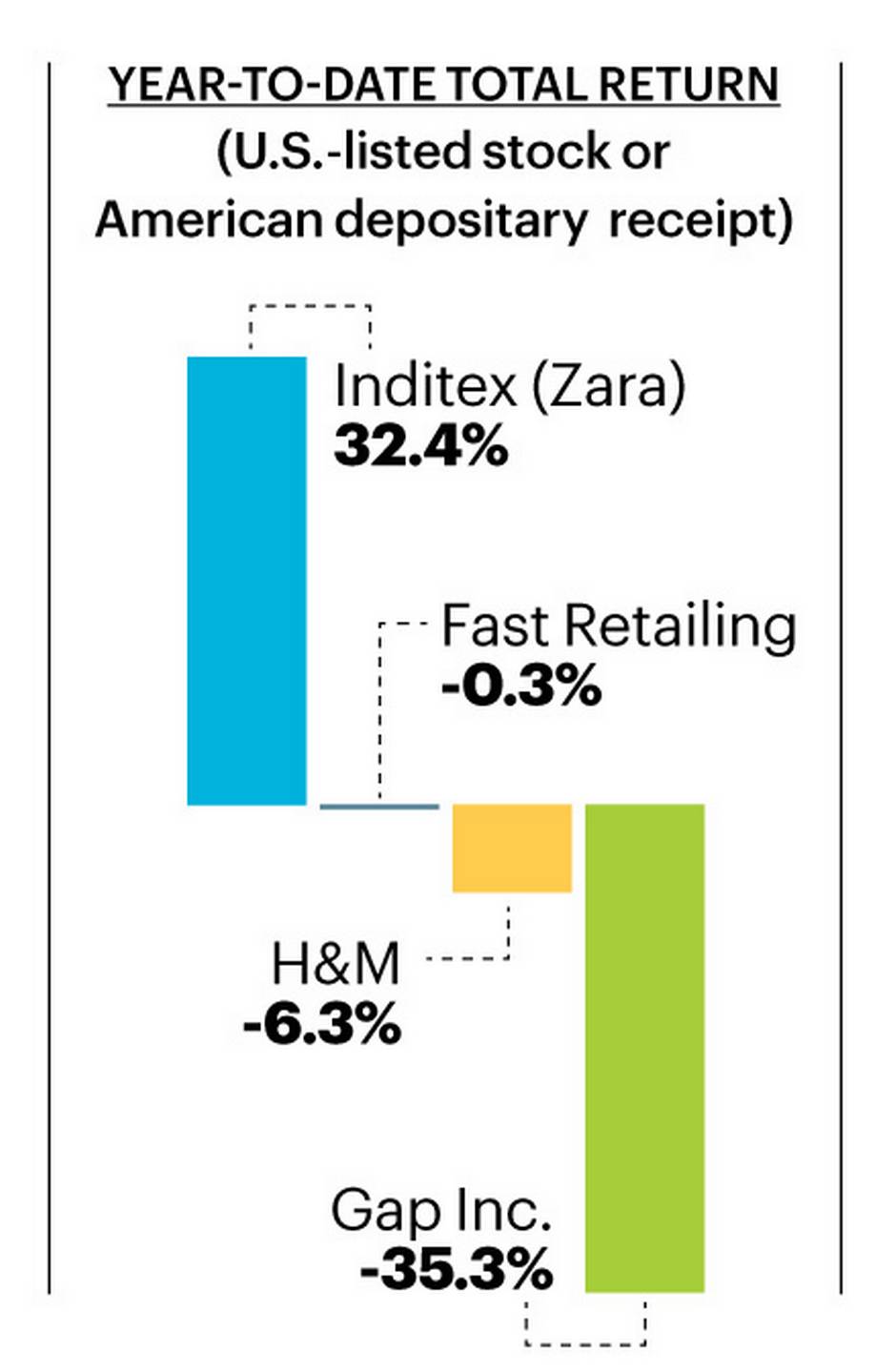

Who’s the biggest? That would be Spain’s Industria de Diseño Textil SA, or Inditex, the parent of Zara and several other brands. It has more than 6,600 stores in 88 markets and the share price is factoring in more growth ahead. Inditex’s shares have surged 42% this year, driven by analysts’ forecasts that profits will rise 16% in 2015, and by an awe-inspiring business model that has not faltered. Zara produces 18,000 designs each year, with new concepts developed in an average of just three weeks.

The contrast with the old guard is striking. By stubbornly sticking to outdated strategies and styles — essential khakis, anyone?—many traditional chains have actually fuelled fast-fashion’s growth with their own decline. Gap Inc. used to be the world’s top clothing retailer, but its sales keep slumping as younger consumers turn away. In June, the company announced that it would shutter a quarter of its Gap stores in North America, though its Old Navy chain is performing considerably better.

The list of other retail clothing casualties is long: American Apparel filed for bankruptcy protection in October. J.Crew is reporting falling same-store sales. Fashion icon Ralph Lauren stepped down from his eponymous chain in September, leaving deteriorating sales and a brand that is now described as stodgy.

These setbacks have sent the stocks of several struggling retailers into the bargain bin. Gap’s share price has fallen toward three-year lows. The stock’s price-to-earnings ratio is now below 10, down from about 20 just three years ago. That price decline has boosted its dividend yield to an attractive 3.4%, yet investors are still wary.

Even at severely reduced prices, unfashionable retailers can be a dangerous bet. Retail consultants say that brand perception is often unalterable. In other words, out-of-favour retail stocks are altogether different than more reliably cyclical plays on banks, utilities and energy producers. Some retailers may never come back in favour.

So does that mean you should bet on H&M, Inditex or Japan's Fast Retailing, the parent company of the Uniqlo chain? Uniqlo is set to open its first two stores in Canada next year. Sure, there are risks with those stocks, too. A business concept based on buying cheap clothes and then discarding them within a season can rile critics and alienate consumers. Many felt at least a twinge of guilt after an apparel factory complex collapsed in Bangladesh in 2013, killing 1,100 workers.

The history of business is also full of examples of disrupters being disrupted. Newer brands such as Primark, Missguided, Boohoo and Nasty Gal are moving up, many of them with a particular focus on online retailing.

For the most part, however, the upside with the fast-fashion leaders seems to outweigh the risks. Despite their enormous size, H&M and Zara still have room to grow. In July, H&M launched makeup and skin-care products with its H&M Beauty line, essentially applying fast-fashion concepts to cosmetics. It is also pushing hard to expand in the U.S., where its market share still lags Gap.

Zara is integrating online sales with its in-store operations, and says it is attracting millions of shoppers without cannibalizing sales from its physical stores. In Tokyo, Fast Retailing’s charismatic founder, Tadashi Yanai, wants Uniqlo to surpass Zara and become the world’s biggest private-label brand.

Yes, the stocks are no bargains. H&M trades at about 25 times trailing earnings, Inditex at 39 and Fast Retailing at 41. These valuations suggest that strong growth prospects are built into the share prices. But none of the stocks are frothy. They have been rising steadily, rather than parabolically, reflecting real growth, rather than investor infatuation. Cheap and trendy has its rewards.