At Kenya park, ‘People’s Parliament’ keeps up grass-roots sessions

The Jeevanjee Gardens, a verdant pocket in the bustle of Nairobi, Kenya’s capital, is loved by the citizenry, but not for tranquillity.

A woman in a bright-pink business suit claps her hands, stamps her heels and sings. Nearby, under a canopy of trees, a preacher hectors a few people on the imminent coming of the “end days.” At the other end of the park, two more plaza prelates progressively ratchet up the volume to drown each other out.

But the garden is best known as the home of the Bunge La Mwananchi, Kenya’s so-called People’s Parliament, a cacophony of thinkers and talkers, debaters and activists, reformers and dreamers, who meet daily to debate the issues of the moment. They cram around several benches under a tree and engage in clamorous discussion.

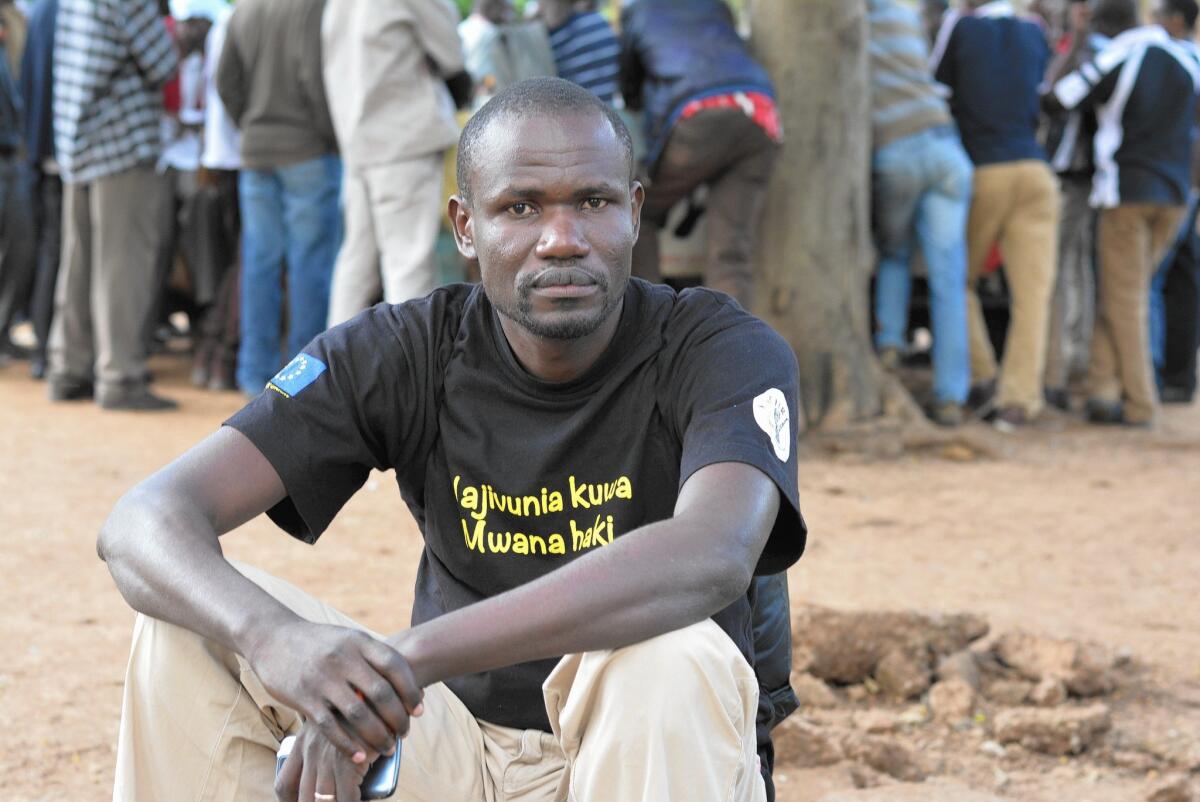

“We are not registered so the government can’t de-register us. We prefer it that way,” said the group’s coordinator, Wilfred Olal, 35, who’s been arrested more than 10 times.

Members of the informal group, which has been meeting here since 1991, just turn up. Then they wait to stand and speak their minds. But there are also rules, traditions, biennial elections and officeholders, including a president, speaker and coordinator.

Olal stumbled across the People’s Parliament in 2006 as he hurried to an appointment. In the park again a few days later, he listened to the debate and decided it “wasn’t bad.” He began attending daily, unearthing an inner passion for human rights.

He calls himself a “defender,” someone willing to put himself on the line to defend others’ rights.

“You just come and listen and share ideas,” he said. “From there, you get human rights defenders, you have politicians, we have lawyers, we have students from the University of Nairobi, and jobless people.”

The People’s Parliament, he said, offers ordinary people a chance to debate, learn and eventually take on the government.

“We are always fighting someone, trying to make things better for the future of this country,” Olal said in a soft, almost inaudible voice. “The problem with political parties in Kenya is that they’re not ideological. They’re tribal.”

The first time he tried defending human rights, at age 19 — well before he joined the People’s Parliament — he mobilized his neighborhood to detain a rape suspect.

It didn’t go well. The suspect’s family, he said, bribed the victim’s mother to drop the charges, and police told Olal to mind his own business. The girl and her mother then disappeared.

“It left me with a lot of egg on my face.”

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

Years later, he said, he met the girl’s mother, who told him she was also paid to leave town. She said she couldn’t turn the money down. As a slum dweller, it was more money than she could imagine.

But the incident resulted in a passion for activism. Olal eventually became the main coordinator of the People’s Parliament and has organized demonstrations and protests and run campaigns against killings by police, gender-based violence and even high prices.

“I’m getting used to being arrested,” he said wryly.

The People’s Parliament was formed during Kenya’s rule as a one-party state under President Daniel Arap Moi.

“When the government discovered this was going on, they just started arresting people,” Olal said. “Moi didn’t like these meetings. But the more they were arrested, the more they came.”

The year that the People’s Parliament was formed, there were moves to put up a shopping center and a parking lot on the valuable chunk of city land. In 2007, there was another attempt to turn the site into a shopping mall.

Olal works as a trader, selling car parts to auto repair businesses. His parents died when he was a child and he struggled and scraped to finish school. He doesn’t have a car so he lugs the auto parts in boxes, door to door. He lives in Dandora, the site of one of Nairobi’s biggest dumps, controlled by rival armed gangs who charge people to dump their waste.

Olal, who says the dump is the cause of respiratory infections and other illnesses in the slum, called for the site to be closed down. Thugs from rival gangs threatened to kill him.

The People’s Parliament meets almost every day in Jeevanjee Gardens. Before President Obama’s recent visit to Kenya, the group condemned U.S. policy in Africa and elsewhere. That week, many spoke out against America’s support for gay rights. In one raucous session, older members of the group advised their young comrades on how to meet girls.

Most days, business is more serious.

“My dream is just to make this country change where, whether you are the son of a poor man or the son of a rich man, you go to school up to university and when you are sick you can go to hospital without friction,” Olal said.

Social media in Kenya have made life easier for Olal and other “defenders.”

“We used to have to rely on the media and they didn’t run our stories. It’s easier now. You just put it out on social media, and it starts trending.”

ALSO:

Sierra Leone’s last known Ebola patient is discharged singing and dancing

The hidden consequences of hunting Africa’s lions

Oscar Pistorius to stay behind bars -- for now

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.