The Oxford dictionary has announced its word of the year. It’s spelled ... Actually, it isn’t spelled at all, because it contains no letters, just a pair of symmetrical eyebrows, eyes, big gloopy tears, and a broad monotooth grin. That’s right, the word of the year is the “face with tears of joy” emoji.

But that’s not a word at all! If the Oxford dictionary is not going to take the meaning of the word “word” literally, then who is? Caspar Grathwohl, president of Oxford Dictionaries, laughs. Not so much that he’s leaking tears of joy, but he definitely sounds amused. He oversaw the discussions that led to the selection. “We just thought, when you look back at the year in language, one of the most striking things was that, in terms of written communication, the most ascendant aspect of it wasn’t a word at all, it was emoji culture.” He mentions Hillary Clinton, who tweeted students, asking them to tell her how they felt about their loans “in three emojis or less”. Then Moby-Dick was translated into emojis (and renamed Emoji Dick.) Alice in Wonderland underwent the same update – a task that required the use of 250,000 emojis. The author TR Richmond, who used emojis in What She Left, a novel built around texts, blogs and Facebook posts, says that emojis “have a place at the heart of our language”.

“The fact that English alone is proving insufficient to meet the needs of 21st-century digital communication is a huge shift,” says Grathwohl. When one of his dictionary colleagues suggested using an emoji instead of the word “emoji”, “lightbulbs went off”. (This hints that he also thinks in emoji.) Until recently, Grathwohl, who is 44, avoided using emojis altogether because he worried that he would look as if he “was trying to get in on teen culture. I felt inauthentic. But I think there was a tipping point this year. It’s now moved into the mainstream.” Not only does he use emojis – his favourite is the ghost, which he uses in place of “I”, sharing as he does a first name with Caspar the Friendly Ghost – but his mother sends him emoji-laden messages, too.

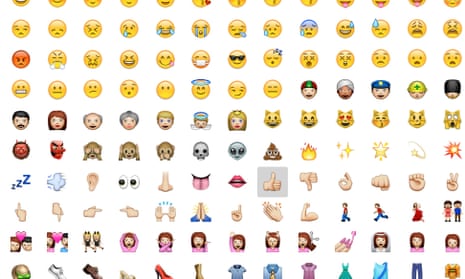

Three or four years ago, Oxford Dictionaries’ announcement would have been subversive, but now it seems a reasonable reflection of the way that language is shifting. Some 76% of the UK adult population owns a smartphone, and of those, between 80% and 90% use emojis. Worldwide, six billion are sent daily. The “face with tears of joy” is the most used, representing 20% of all UK and 17% of all US emoji use. It has overtaken the standard smiley-face emoji in popularity, which may mean that emoji users are moving towards exaggeration or irony or fun, or that all this emoji use has brought everyone to a higher emotional plane. Even if you don’t send emojis yourself, you will probably receive them – from younger or less grumpy-faced folk. (In the UK, a third of over-40s have never used an emoji.)

In fact, emojis have their own version of the Oxford dictionary. It’s called Unicode, a California-based consortium that ensures different platforms, providers and operating systems can recognise text from each other. There are now 1,282 emojis – all listed in Unicode’s emoji dictionary – although most operating systems provide access to only 800.

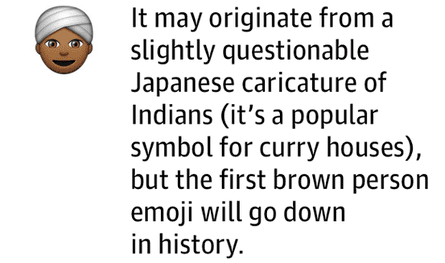

Anyone can suggest an emoji, says Vyvyan Evans, a professor in linguistics at Bangor University, who has spent the past year studying emojis. He became interested in them after he saw news reports in January of a Brooklyn teen who was arrested for using a police emoji next to two gun emojis on his Facebook page. “You simply submit a proposal, provide a rationale.” The Unicode tech committee considers suggestions and releases new outlines of characters in a process that can take about two years. As a result of these innovations, racially diverse emoji have been introduced. Next year, a dancing man is coming, partner to the dancing lady. Vegetables remain under-represented, small rodents overly so.

But how far do emojis function as a language in their own right? “There’s a lot of prejudice against emojis,” Evans says. (The dancing lady, “inherently sexy”, is his favourite.) “A lot of people think they are a backward step, but this misunderstands the nature of human communication.” The picture is more complicated, with emojis offering both greater freedom and constraints than verbal language. He points out that anyone can invent a word and use it, but emojis are a limited language, subject to the controls and selection processes of Unicode. “Emoji isn’t a language as such. They are artificially created. They don’t evolve in the way that the natural language does. They don’t have a grammatical system. What I’ve been trying to do is demonstrate that emoji are conforming to the same principles of communication that underpin the spoken language. What is the value of an emoji? I think I can demonstrate this with a bog-standard sentence.” There is a pause. “I love you,” he says. Crikey. He says it twice. The first time I think he means it; the second time we both know he doesn’t. “The meaning is coming from extra-linguistic factors,” he says. “Emojis are fulfilling the same function in digital speech.” They are a way of smiling in the face of limited time and limited space to let people know you are digitally happy (even if you are, in person, deeply troubled).

It was in Japan, in the late 1990s, that emoji were born. The Japanese telecom company NTT DoCoMo, which had previously used the gimmick of a heart symbol in its text facility, had been looking for a way to entice teens to its pager service. One of its employees, Shigetaka Kurita, came up with the idea of adding simple images to its text offering, and with pencil and paper began sketching out the possibilities. Kurita’s first emojis were just 12 by 12 pixels in size. Inspired by manga, Chinese characters and street signs, they look simple by today’s standards – facial expressions more than faces, musical notes, exclamation marks.

There had been early precursors (for instance, a range of emoticons appeared in the 1881 edition of US magazine Puck). But Kurita’s initial batch of 176 captured a broad sweep of human emotion and laid down a template for a more detailed emoji lexion to follow.

Emojis were, to begin with, a uniquely Japanese phenomenon. NTT DoCoMo’s competitors adopted them. According to New York magazine, when Apple released its first iPhone in 2007, it included an emoji keyboard, intended only for users in Japan. But after US users discovered that downloading a Japanese language app would trigger access to the keyboard, pressure to open up the offering grew. In 2011, the emoji keyboard became an international standard on iOS.

Like any sort-of language, emoji is evolving, not only in the 2D choices it offers, but in the way that texters and typers are choosing to deploy them. “I do think they are subtle and rich,” Grathwohl says. “They are so flexible. They can mean different things to different people. So I send, I don’t know, an aubergine to one person and it might mean something very different to another person.” Isn’t that the cheeky one? “It is a little cheeky, absolutely. I do think that the strings people send to me are becoming longer and longer. They are starting to tell stories in and of themselves. The fact that we are using emoji in combination to express more complex ideas and experiences is one of the most fun and playful parts of the whole script. Will emoji eventually be tamed and come to look something more like traditional language scripts that we understand?” he asks. “That would be interesting.”

In the meantime, the face with tears of joy may be the word of the year, but it hasn’t yet earned a place in the dictionary itself. Maybe they are still trying to work out where it would sit.

More than words can say

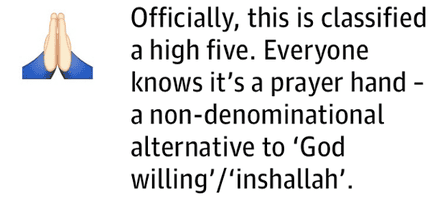

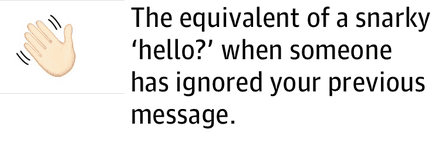

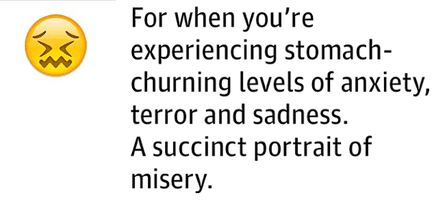

A guide by Sara Ilyas

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion