The government recently published its latest estimates of economic growth, employment and exports for the UK's creative industries. They show a continued strong performance in 2013, despite a small dip in the ‘Film, TV, video, radio and photography’ group. What's most striking about the data are the comparisons with the rest of the UK economy. Over a sustained period the creative industries have grown much faster than the wider UK economy on all three measures.

The creative industries are where the UK has a definite competitive advantage in the 'global race'. Last year, nine of the top ten biggest selling artist albums were from British acts. This country is the second largest exporter of TV programmes and has many of the most widely used news websites in the world.

Moreover, there is evidence that strong creative industries spur growth in the wider economy and make the UK a more attractive place to do business with. It's likely that most UK economic growth in the next decade will come from cities and we know from places like Manchester/Salford, Bristol, Cardiff and Glasgow, that thriving arts and culture can act as a catalyst for urban renewal.

So the key question for policy-makers is not ‘it’s broke, how do we fix it?’ but ‘it works, how do we sustain it?’ In this post, I want to consider the difference the BBC makes to the creative industries.

I should start by saying that the BBC's primary purpose is public not economic. It exists to provide great content that educates, informs and entertains, and to deliver social, cultural and civic benefits. This is why the BBC is publicly funded and made universally available.

At the same time, this purpose means that the BBC invests in home-grown creative ideas and talent (writers, producers, actors, journalists and musicians), and its funding model enables it to do so at scale and to take risks and innovate across content and technology. Economic value is, therefore, an important side-effect of the BBC's public purpose.

Whether by design or not, the BBC has the effect of a major industrial policy intervention in the UK creative economy and one that, judging by the performance of creative industries, seems to have had a net positive effect. This shouldn't be a surprise as we know markets tend to work best when properly regulated and shaped by smart public policies. A lot of innovation in modern economies is facilitated by what's been called the 'entrepreneurial state' - governments, public agencies and universities. Mariana Mazzacato has written extensively about this; see for example, The Entrepreneurial State. Look at how the internet and subsequently the worldwide web originated in the pioneering work of public agencies, the US government's Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) and CERN (the European Organization for Nuclear Research) respectively.

Previous analysis has looked at the value generated for the UK economy by BBC activity, using multiplier analysis. In 2012, BBC spending generated gross value added of around £8 billion - that's £2 of value for every £1 of licence fee spent. To build on this analysis, we've looked at how the BBC helps to create the conditions - in terms of investment, competition, skills and training, and innovation - for a high growth creative economy.

The UK's network of creative industries

The UK’s creative industries can be viewed as a complex network, with strong inter-relationships and dependencies between many of the constituent parts. Inter-connections exist both between different creative content sectors - e.g. TV and film, radio and music, and TV/radio and the performing arts and museums and galleries - and between different players within each sector. Many modern academic accounts of the origin of ideas and innovation stress the importance of connectedness. Ideas - carried by people - collide with each other. They come together, producing more than the sum of their parts.

Public-private competition is also a pivotal feature of the creative economy. In broadcasting (as in the arts), 'competition for quality' between public institutions like the BBC and commercial broadcasters like ITV and BSkyB has led to higher levels of investment and better, more varied output. When the BBC performs well, others have to raise their game to compete for audiences, which challenges the BBC to aim higher - in a positive feedback loop. Far from crowding-out commercial investment, I'd argue that the BBC supports overall market growth. This is a dynamic that can be observed in other countries with strong public service and commercial broadcasters.

The BBC's role in the creative industries

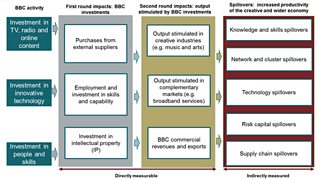

The BBC occupies a hub position in the UK’s creative industries, densely connected to many other firms through supply-chain linkages, induced investments and positive spillovers. It is these inter-connections that power the BBC's contribution to growth, jobs and exports. Working with Frontier Economics, we’ve identified a three-stage 'transmission mechanism' through which the BBC contributes to growth in the UK’s creative industries. This is shown in the graphic below (with more detail to follow in subsequent posts):

BBC transmission mechanism

First-round effects: These reflect the BBC’s direct investments in the creative industries. It is estimated that in 2013/14 the BBC invested around c.£2.2 billion of licence fee income into the creative industries, by producing and purchasing goods and services, from TV programmes to web apps. This included c.£1.2 billion outside the BBC, with around £450 million on small and micro-sized creative businesses. The BBC supported over 2,700 creative suppliers and over 80% of those were small or micro-sized. A further £1.5 billion was invested outside of the creative industries in the UK; much of this spend was in the digital and high-tech industries on activities which support content creation and content distribution.

While the licence fee accounts for c22% of UK TV broadcast revenues, it is converted into c42% of the investment in original UK TV content. The effect is to increase the overall level of stable demand in the creative economy and provide risk capital for ideas and talent. In some cases, these ideas and talent go on to generate big economic returns through secondary sales and global exports.

This brings me to the second-round effects of BBC activity through the commercial exploitation of intellectual property and by stimulating additional demand and output in connected industries like music.

The BBC's Dancing with the Stars (the international version of Strictly Come Dancing), for example, is now licensed to over 50 countries and in the US it was ABC’s highest rating programme of 2014. BBC Worldwide represents content from over 250 British independent production companies and is the largest distributor of finished TV programmes outside the major US studios. At its core, the BBC connects great ideas with funding and with an audience, and acts as the best ‘shop window’ to the world for UK talent and programme-makers.

The ‘ripple effects’ from the BBC’s investments in content and technology go far and wide in the creative economy.

Take, for example, the music industry and the increased record sales and exposure for new British artists associated with the BBC’s extensive radio airplay. The naming of Sam Smith - now a global star - as 'BBC Sound of 2014' in early January led to a spike in his album sales - they rose from 1,000th on Amazon to 6th in the following twenty-four hours.

Or look at how the invention of the BBC iPlayer acted as a catalyst for the development of video on-demand (VoD) and generated demand for broadband connectivity. Back in the mid-2000s, the BBC was able to overcome the uncertain investment conditions and co-ordination problems associated with VoD. Its Charter-based mission to 'bring new digital technologies to everyone' gave it a mandate and its funding model, expertise and trusted brand gave it the means. The success of BBC iPlayer changed consumer behaviour and increased demand for VoD services to the benefit of all market participants. Reed Hastings, Chief Executive of Netflix, recently said: ‘‘The iPlayer really blazed the trail. That was long before Netflix and really got people used to this idea of on-demand viewing.’’ The UK now has by far the largest on-demand video market in Europe.

Positive spillovers: the BBC's activity has spillover effects that strengthen the productive capabilities of the creative economy. These are hard to quantify but important nonetheless. Public institutions like the BBC and Channel 4 nurture the creative talent and expertise which the sector needs to flourish. Oscar-winning directors such as Danny Boyle and Tom Hooper, or global acting stars such Martin Freeman and Daniel Craig, or two of this year’s nominees for Best Actress Oscar, Rosamund Pike and Felicity Jones, all had early breaks on the BBC. Or think about the next generation of British musical talent championed by BBC Introducing – 25 artists have signed to major record labels in the past 12 months. Similarly, the BBC's role in training and skills development including apprentices - when combined with high labour mobility - benefits the creative content industries.

It is often easiest for inter-connected organisations to share knowledge, skills and ideas when geographically located together. During this Charter period, the BBC has devolved significant activities outside London and the South East, and has acted as an anchor tenant for 'clusters' of creative businesses in different parts of the UK. MediaCityUK - with c.200 firms and c.6,400 jobs – has become one of the largest media clusters in Europe and a recent NESTA report reveals that a number of UK cities now have concentrations of creative sector activity.

All of this sounds fine, you may say, but what about the counterfactual and the opportunity cost of the BBC?

Even if you accept that the BBC has some economic benefits, there remains the question of would the UK creative economy be just as successful without the BBC? For the answer to be 'yes', you'd need to believe that: a) the BBC crowds-out private investment to a significant degree, so that its economic effects are not truly additional, and b) that the broadcast market, funded by subscriptions and advertising alone, would fill the huge investment gap left by the BBC. Such assumptions are based on simplistic theories that misread how the UK’s mixed broadcasting model works. More importantly, they are not supported by the evidence. On the contrary - empirical analysis of 'what if there were no BBC television' demonstrates that UK broadcasting would be significantly smaller - and audiences would be worse off.

From an economy-wide perspective, the allocation of scarce resources to the BBC via the licence fee doesn't look like a bad choice either, given the comparatively high growth rate of the creative sector and its positive spillovers to the wider economy. And this is, of course, before you consider the BBC's audience and wider public benefits.

Few other countries are in better creative shape than the UK. This hasn’t come about by accident but is, at least in part, because of this country’s vision and foresight in establishing strong public institutions. The BBC continues to act as an engine of investment in British creativity and culture. The debate at charter review should be about how to strengthen this role not diminish it.

James Heath is Director of Policy, BBC

- Read John Dickie's blog 'Yes, but what’s the BBC ever done for us?'

- Read the BBC's Contribution to the Creative Industries report on the Inside the BBC website.