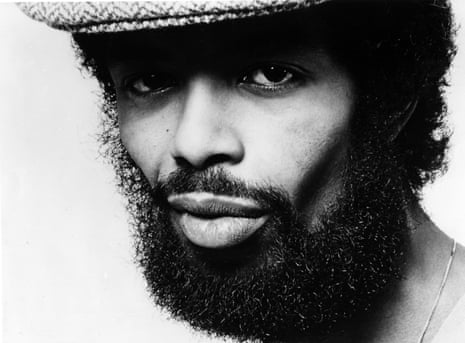

When Gil Scott-Heron died in May 2011, Public Enemy’s Chuck D hailed him as “the manifestation of the modern word”. At his funeral, Kanye West performed Lost in the World/Who Will Survive in America, which sampled his spoken word . During the attempt to overthrow Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak, Scott-Heron’s most famous track, The Revolution Will Not Be Televised, was playing in Tahrir Square.

“Gil was a legend to me as a kid,” says rapper Talib Kweli, one of several artists appearing at The Revolution Will Be Live, a concert tribute to Gil Scott-Heron in Liverpool. “Kanye West, Jay Z, Ice Cube … mention Gil Scott-Heron and they will go on about how he’s influenced them. Put it this way: without Gil Scott-Heron there would be no Kanye talking about New Slaves.”

From Kweli and Kanye to Kendrick Lamar, Scott-Heron’s catalogue has long been a vital source of inspiration for hip-hop artists. But his influence is far broader than just music. He has been a guiding light as a singer and proto-rapper, novelist and poet, teacher and civil-rights activist.

At the concert, Kweli will be joined by actor and broadcaster Craig Charles, reggae band Aswad, Liverpool pop-soul group the Christians, who had a hit in 1993 with a cover of Scott-Heron’s 1974 popular single The Bottle, his protege Abdul Malik Al Nasir, his son Rumal Rackley and guest of honour Ndaba Mandela, grandson of Nelson. It will be a day of celebration, if not an opportunity to explore the conflicted individual behind the growing myth.

Scott-Heron was a high-achieving polymath, so there is plenty to laud: he was a novelist by 20, while his 1970 album of politicised, rhythmic spoken word, Small Talk at 125th and Lenox, preceded rap by a decade. Without his pioneering contributions, Al Nasir believes hip-hop wouldn’t have evolved beyond good-time party music.

“It would have just been Rapper’s Delight,” he says.

Throughout the 1970s and early 80s, Scott-Heron used his songs to rail against the Vietnam war, the perils of alcohol and narcotics, the Watergate scandal and racial injustice, although these pieces – created with principal collaborator Brian Jackson – were generally harmonious fusions of soul, jazz, blues and funk, rather than diatribes. Pieces of a Man (1971) and Winter in America (1974) are regarded as the forerunners of both conscious soul (such as Raphael Saadiq and D’Angelo) and conscious rap: Lamar and J Cole are, as Kweli states, “two of the biggest artists in America – Gil is all over popular music right now.”

Scott-Heron’s political activities – tackling the dangers of nuclear power via the No Nukes shows at Madison Square Garden in 1979, campaigning in 1981 with Stevie Wonder to make Martin Luther King’s birthday a national holiday and his involvement with the Artists United Against Apartheid movement – are well documented. But by the mid-80s, he had succumbed to drug addiction, seemingly drawn into the spiral of self-abuse he had spent the previous decade damning. In his final years, he was jailed for possession of crack and cocaine and was diagnosed HIV positive. And yet when he released his first album for 14 years – I’m New Here, in 2010, which turned out to be his last – it was as a returning champion, not a victim.

Nevertheless, there is a sense of Scott-Heron as tragic underachiever – someone who never reaped the same commercial rewards as Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, Curtis Mayfield and Sly Stone, yet whose records were also hard-hitting – and as multivalent innovator. Since his death, he has been variously cited as “the black Dylan” and “the godfather of rap”.

In 2010, Charles interviewed Scott-Heron for BBC Radio 6 Music. “He was really grouchy and wasn’t keen on looking back,” remembers the DJ. “Every time I’d ask a question about his past, he’d fly off the handle. He came across as angry and frustrated,” recalls Charles. “But he’s still one of the most intelligent poets ever. His records are seminal for anyone who knows their political funk and soul. And his final album was brilliant, even if it was dark – even frightening – in places. He was always a trailblazer.” (Indeed, Jamie xx released a remix of that final album, We’re New Here, was a year later).

“I don’t think his influence can be overstated,” says Charles. “For black America, he was their greatest folk hero. He just couldn’t beat his addictions.” But Al Nasir says it is misguided to regard Scott-Heron’s later years as a descent into poverty and addiction.

“He wasn’t impoverished – don’t get it twisted,” he says, testily. “He could have had seven figures in the bank, but that wouldn’t stop him living in a single room in Harlem. Why? Because he was a humble man. He didn’t like the trappings of wealth. He was generous and kind. One of the values inculcated in him by his grandmother was: if you can help someone, why wouldn’t you?”

In 1984, a chance encounter between Scott-Heron and Al Nasir, then a self-described “illiterate street kid” in Liverpool, led to him taking the 18-year-old under his wing. Today, Al Nasir boasts a master’s degree and is sensitive about press intrusions into his mentor’s personal life. “If you want to talk about [crack], you’re talking to the wrong guy,” he warns. “I don’t get involved in trying to take down the man who raised me up. If he’d sat in judgment over me when I was 18, I’d probably be dead now.”

Kweli is also sympathetic to Scott-Heron’s dark side. “Gil had famously bad habits, and of course there were things that made me sad, but disappointed? No. Who am I to be disappointed by someone’s personal demons? If anything, I think he was courageous to bare his soul the way he did.”

Naturally, everyone involved in The Revolution Will Be Live is a paid-up member of the Scott-Heron fanclub. To Garry Christian, he was “a poet who spoke about what was wrong with society”, his music continually relevant, “especially now, when cops are killing black people”. Ndaba Mandela, who is giving a lecture on slavery the weekend of the concert in Liverpool, is grateful for his pursuit of equality. “It won’t grow automatically,” he says of Scott-Heron’s legacy, which he likens to that of his grandfather. “Even the old man, eventually, if we don’t continue his work, people will forget.”

Promoter Richard McGinnis sees the event, ultimately, as “a bookend to Malik’s story. It’s his way of thanking Gil for putting him through university,” he says. “For seeing the good in him when he was destitute.”

What does Al Nasir consider to be an appropriate memorial? “Gil wouldn’t want to be canonised. He had a similar perspective to Mandela – he didn’t want statues. He was a complex character, a troubled soul. He wasn’t perfect. But what he did have was sincerity, and heart. He wanted to raise consciousness and make the world a better place.”

The Revolution Will Be Live is on 27 August at the Liverpool International Music festival.

Pieces of a Man

The Revolution Will Not Be Televised

This was originally a spoken-word piece from 1970 and rerecorded with a band in 71. You could draw a straight line all the way from this thrilling piece of invective to Public

Home Is Where the Hatred Is

Sampled by Kanye West on My Way Home , this grim depiction of ghetto misery and narcotic misadventures assumed a new resonance in the light of Scott-Heron’s own drug addiction.

Lady Day and John Coltrane

A 1971 homage to two inspirational jazz figures, its lyric about seeking solace in the work of greats could have been penned about Scott-Heron himself.

Winter in America

Not originally featured on the 1974 album of the same name, this was typical Gil: an apocalyptic vision of the US, accessibly presented, flutes and all.

H²Ogate Blues

A lengthy dissection of the corrupt Nixon administration and the America of Watergate and Vietnam, set to insidious proto-rap.

The Bottle

Although dark comment on alcohol abuse from 1974, this was a melodic and funky affair.

Johannesburg

A prime example of Scott-Heron’s expansive vision, this jubilant 1975 single tackled the issue of apartheid in South Africa.

Angel Dust

Recorded with Malcolm Cecil, one half of Stevie Wonder’s classic-era production team, this 1978 track was about as mellifluously mesmerising about a killer drug as you could get.

B-Movie

This 1981 track – with its now-famous opening “The first thing I want to say is, ‘Mandate my ass’” – was a diatribe against the election of a former B-movie actor to the White House.

Me and the Devil

The only single lifted from his 13th and final album, I’m New Here (2010), this was a riveting, rasping electronic adaptation of Robert Johnson’s Me and the Devil Blues (1937).

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion