Editor's Note: Five years ago, Globe reporters and photographers walked the May 22, 2011, devastation from Schifferdecker Avenue to Duquesne, describing what was happening, what people were doing and interviewing survivors. This past spring, they returned.

———

Five years after the Joplin tornado, signs of recovery are everywhere — in the green leaves that burst forth this spring on the thousands of newly planted trees, on the bright facades of new schools, on the glowing butterflies that have become a symbol of the community's rebirth.

But one corner of Joplin remains untouched. The bedroom of Will Norton — one of the first victims of the storm — remains as he left it five years ago, right down to the socks sitting underneath the desk.

Change has come for Will's parents as well, but it's not in the same spirit as the rest of Joplin. His father, Mark Norton, talks of low days without the balance of happier days, of seeing the world in black and white after his son's death.

"Really, it's like life lost color," he said.

The EF-5 tornado of May 22, 2011 — the nation's deadliest in nearly 70 years — carved a six-mile path of destruction through one-third of Joplin and Duquesne, destroying or damaging an estimated 8,000 structures and injuring more than 1,000 people. When all was said and done, 161 people lost their lives.

In the five years since, residents of both communities have undergone a miraculous journey of healing and recovery, working to put their cities back together. But even if many of the neighborhoods, schools and businesses have returned, for some, the journey back is far from over.

WILL'S LEGACY

Will had received his diploma from Joplin High School approximately 40 minutes before the tornado exploded. He and his father were in their vehicle on their way back home to southwest Joplin when tragedy struck.

The 18-year-old, who was torn out of the vehicle despite his father's attempts to hold onto him, would become one of the tornado's first victims, although his body wouldn't be recovered from a pond along Schifferdecker Avenue for nearly a week.

Five years later, Mark Norton tries not to think about that day.

"You don't want to let your mind go there too often, but it's there in your thoughts and dreams," he said.

Wishing to focus on what his son left behind rather than the manner of his death, Norton has seen Will's legacy emerge in numerous ways since the tornado. Will's Place, a healing center for children, opened in January 2012 through the Ozark Center. Chapman University in Orange, California, where Will had planned to study filmmaking, launched the Will Norton Presidential Scholarship. And the Will Norton Miracle Field, built in the Joplin Athletic Complex largely by donations through Rotary Club, opened for its first season in 2013.

It's the Miracle Field, where children and teens with disabilities can play ball, that means the most to Norton. He said Will would have been the first to volunteer at the field. Norton himself, along with his wife, Trish, can often be found at the field during games, working in whatever capacity is needed.

"It's 100 percent Will, and I know he would love to have his name with this," Norton said. "It's not that we have to have Will's name everywhere, but it's nice to see him associated with things he would have liked."

The parents continue to see Will's lasting impact in more personal ways as well. A pair of out-of-town women who were visiting Joplin's tornado memorials stopped to chat with Norton at the Miracle Field during the first game of the current season. One of the women pressed a $100 bill — her donation to the field — into his hands before she left. A few moments later, she was back again: "I can't wait to meet your son in Heaven," she told him.

"His whole life was about helping others," Mark said. "It amazes us, the people who still contact us from around the world and say he changed their life. It makes us proud, of course."

Even so, sometimes it's too much. The couple has found that often the best way to escape the memories of five years ago and the resulting reality is to leave Joplin, even temporarily.

"Everywhere we go, there are reminders," Norton said. "It's nice to have Joplin to come home to, but it seems like we can live a little more when we're on the road."

'MIKE, MISS U'

There are still five Stars of Hope tacked to utility poles at the intersection of Schifferdecker Avenue and West 26th Street, where the tornado began growing toward its EF-5 size.

Hung shortly after the storm as part of the New York Says Thank You campaign, the wooden stars are now chipped, the red and blue paint faded. But some words on them still stand out: "Restore," "hope," "faith" and "Mike, miss u."

The 5-year-old stars are among the oldest objects left in the neighborhood, as the side streets are lined with new or renovated houses. Many homeowners are new to the neighborhood, drawn to the area by programs designed to boost regrowth by making home ownership affordable for residents.

The Joplin Homeowners Assistance Program, funded through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, was one that was highly used. The program has provided $13.65 million in assistance for down payments or closing costs to homeowners of 450 homes in the tornado zone since its launch in August 2013, according to the city of Joplin. Of those homeowners, 31 percent came from outside the Joplin metro area.

One of those homeowners, Tiffany Osborne, took advantage of a Rural Development loan, a low-interest loan that was available to those who were buying or remodeling houses in Joplin and Jasper County. She and her 8-month-old daughter were living with her mother elsewhere in Joplin at the time of the tornado.

Five years later, Osborne is the proud owner of a house she built — with the loan's assistance — in the 3000 block of South Monroe Avenue, complete with a storm shelter that she installed last year. Daughter Tatum, now 5, spends her days looking for roly-poly bugs in the front yard and playing with other kids in her neighborhood.

"It's not the shove I wanted, but it's the shove I needed," she said of the tornado's forcing her out on her own.

A few blocks east at 1802 W. 26th St., the new 9,000-square-foot Joplin Elks Lodge 501 stands atop a hill, overlooking a broad, grassy lawn. It opened in January 2013; since then, membership has grown by about 100 to approximately 700 total members, historian and past exalted ruler Jim Willis said.

The lodge's recovery process is virtually finished, he said.

"I loved the old lodge," he said, reflecting on pre-tornado times. "But I love the new one, too, don't get me wrong."

Just to the east, at the intersection of West 26th Street and Maiden Lane, are two purple Stars of Hope tacked to a utility pole. Five years after she was fatally injured in the storm, 23-year-old Nichole S. Pearish's name is still visible on them.

GROUND ZERO

The area around 26th Street and Maiden Lane/McClelland Boulevard — home to St. John's Regional Medical Center and Cunningham Park — was ground zero for the disaster.

It became ground zero for recovery, too.

Today, Mercy Park, where St. John's once stood, and Cunningham Park are sacred places.

The former, when finished in June, will include woodlands, a meadow and lake, and open green space, dominated by an outdoor chapel and pavilion. The latter now includes a monument, memorial, butterfly garden and overlook, which recall all the homes wiped out by the storm and the experiences of survivors, recognizes the contributions of volunteers, and lists the names of those who died because of the storm.

On a very different May day — cloudless, blue skies — work crews poured concrete in Mercy Park while children, some too young to remember that Sunday, others born afterward, squealed and laughed, climbed and raced through all the features added to Cunningham Park as it was rebuilt, including the "Willdabeast Way," a park feature named for Will Norton.

Nearby, a woman quietly snapped photos in the butterfly garden, bursting with reds, pinks, yellows and oranges.

With so many jobs lost, so much housing destroyed, the question haunting city leaders as they began cleaning up was this: How could the city maintain its population without jobs and homes?

"You always hear after these (natural disasters) that places lose population," said Troy Bolander, manager of planning and community development for Joplin. "We called down to communities that were hit by Hurricane Katrina that were losing 30 percent of their population."

That kind of toll on Joplin would have rolled back the city's population from 50,000 to 35,000.

In all, the tornado damaged or destroyed about 530 businesses — from locally-owned businesses such as Dude's Daylight Donut Shop on Main Street to major retailers on Range Line Road. That wasn't the worst of it, however.

"We had," recalled Rob O'Brian, president of the Joplin Area Chamber of Commerce, "five thousand jobs at risk."

Joplin's recovery, according to business and community leaders, grew out of two early decisions: the commitment by businesses to rebuild, and the decision by many tornado-stricken employers, large and small, to keep paying workers even if the building was rubble.

In both cases, St. John's led the list.

The week of the storm, Lynn Britton, president and CEO of Sisters of Mercy Health System, arrived in Joplin and vowed that the hospital would rebuild, as did many other businesses.

Darren Collins showed up within days of the tornado at Joplin City Hall to get a building permit — the first issued after the storm — to rebuild his wife's salon, Cut Loose, at 2602 S. Byers Ave.

As permits go, it was small compared with some of those that were coming, but the amount didn't matter.

"It wasn't even for a larger business, but it was a permit ... You're sitting there elated," recalled Bolander.

Darren's wife, Diana Collins, still has that permit in a frame at the business. In the corner of the permit, hand written, it says, "#1."

In the nearly five years since the Cut Loose permit was issued, more than $1.25 billion in building permits have been filed with the city. The permit to build the new Mercy Hospital Joplin along Interstate 44, at $269.4 million, was the largest building permit in Joplin's history.

At Walgreens and elsewhere, building crews went to work almost immediately, repairing the Main Street store and rebuilding the Range Line store. Both opened in August, faster than Walgreens had ever built a store. Home Depot, Wal-Mart and Academy Sports and Outdoors all reopened new stores that winter. Dude's and many other businesses returned to Main Street.

But just as the number of businesses destroyed or damaged only hinted at the potential economic blow to the community, the building permits only hint at the investment that has been made in Joplin since the storm.

Gary Pulsipher, president and CEO of Mercy Hospital Joplin, said Mercy spent $160 million on its three interim hospitals and close to $500 million on the final hospital. In all, he said Mercy spent just shy of $1 billion on recovery and rebuilding in Joplin over the past five years.

St. John's also made a decision to keep each of its 2,200 employees on the payroll. Somehow.

"We became a staffing service pretty quickly," Pulsipher recalled five years later. Everyone took whatever jobs were available, regardless of training. People with clinical backgrounds were temporarily helping with security, for example, he said, while oncology staff served as shuttle drivers.

"We shared some of those co-workers with Freeman and with Via Christi (in Pittsburg, Kansas), with Mercy in Springfield," he said of their employees.

In all, more than 200 St. John's employees went to other non-Mercy hospitals and clinics, and hundreds more employees went to Mercy hospitals in the Four-State Area and as far away as St. Louis and Oklahoma City. Many others went back to work in Joplin as Mercy set up the first of three temporary hospitals, each larger than the last.

Walgreens, Wal-Mart, Home Depot and others also kept their people employed. In all, more than 3,000 of those 5,000 workers were ultimately kept on the payroll, according to the chamber.

The recovery has not been perfect. Dillons was the most prominent among the business casualties. Some business owners have expressed frustration with the pace of recovery on 20th Street, in part because the city's comprehensive plan was changed after the storm to convert that area from residential to commercial, and because of the construction of a large viaduct that has closed 20th as a through-street. The project is set for completion this summer.

There are other areas that await redevelopment, including a half-mile stretch of frontage along the north side of 26th Street, from Jackson to Virginia avenues, which includes the former Irving Elementary School, the lot of the former Greenbriar Nursing Home and the corner on Main Street that housed the Salvation Army thrift store before the storm.

According to the chamber, more than 90 percent of the 530 businesses damaged or destroyed on May 22, 2011, have since rebuilt and reopened. And an additional 308 businesses have opened in the two-county Joplin metro area since the tornado, adding 1,045 full-time and 818 part-time jobs.

Five years on, Joplin's population has grown, from 50,175, according to the 2010 census, to 51,300 in 2015.

'MY FIRST FEW STEPS'

Despite the progress, visible reminders of the tornado remain.

One of these is Emerson Elementary School, 301 E. 19th St. The school, badly damaged by the storm, remains standing to this day, its windows and doors boarded shut and its lawns unmowed and unkempt. A total of $300,000 was recently earmarked by the Board of Education for the building's demolition; the district is currently accepting bids for the project.

Across 20th Street, a different approach was taken with the new Joplin High School, a sprawling 488,000-square-foot complex at 2104 Indiana Ave. that includes Franklin Technology Center. The bulk of the rebuilding process for the high school and technical center wrapped up in 2014 at a cost of about $121.5 million.

One of its students is Emily Huddleston, who was left with such a bad injury on her left thigh following the tornado that she had to relearn how to walk. Five years to the day, the 18-year-old will don a cap and gown to walk across the stage to receive her high school diploma.

"For me, it's going to be an emotional day," she said.

It has been an emotional five years for Huddleston as well.

She was at the JHS graduation ceremony on that Sunday in 2011, supporting her older brother, Joe. On their way home, her parents' vehicle unknowingly drove straight into the tornado; winds tossed the Suburban into the air, carrying it five or six blocks. Huddleston used her brother's new diploma to cover her head.

All in the vehicle survived, but something had ripped into Huddleston's left thigh, stripping the flesh and muscle away to the bone. She ended up at a hospital in Parsons, Kansas, where she remained for 11 days. She underwent a blood transfusion and two surgeries to remove debris from her leg and repair the 7-inch-by-5-inch wound.

The next several months were filled with follow-up appointments and physical therapy visits. Huddleston received a synthetic skin graft over her wound, and doctors told her that she would need a walker and would likely never be able to run again. The former track and field athlete was heartbroken.

One day in early August 2011, Huddleston was sitting at home, listening to her family outdoors and staring at her walker from across the room. Frustrated, she made a decision: She would walk again no matter what.

"I remember thinking, 'I'm done with this,' and I got up and took my first few steps," she said.

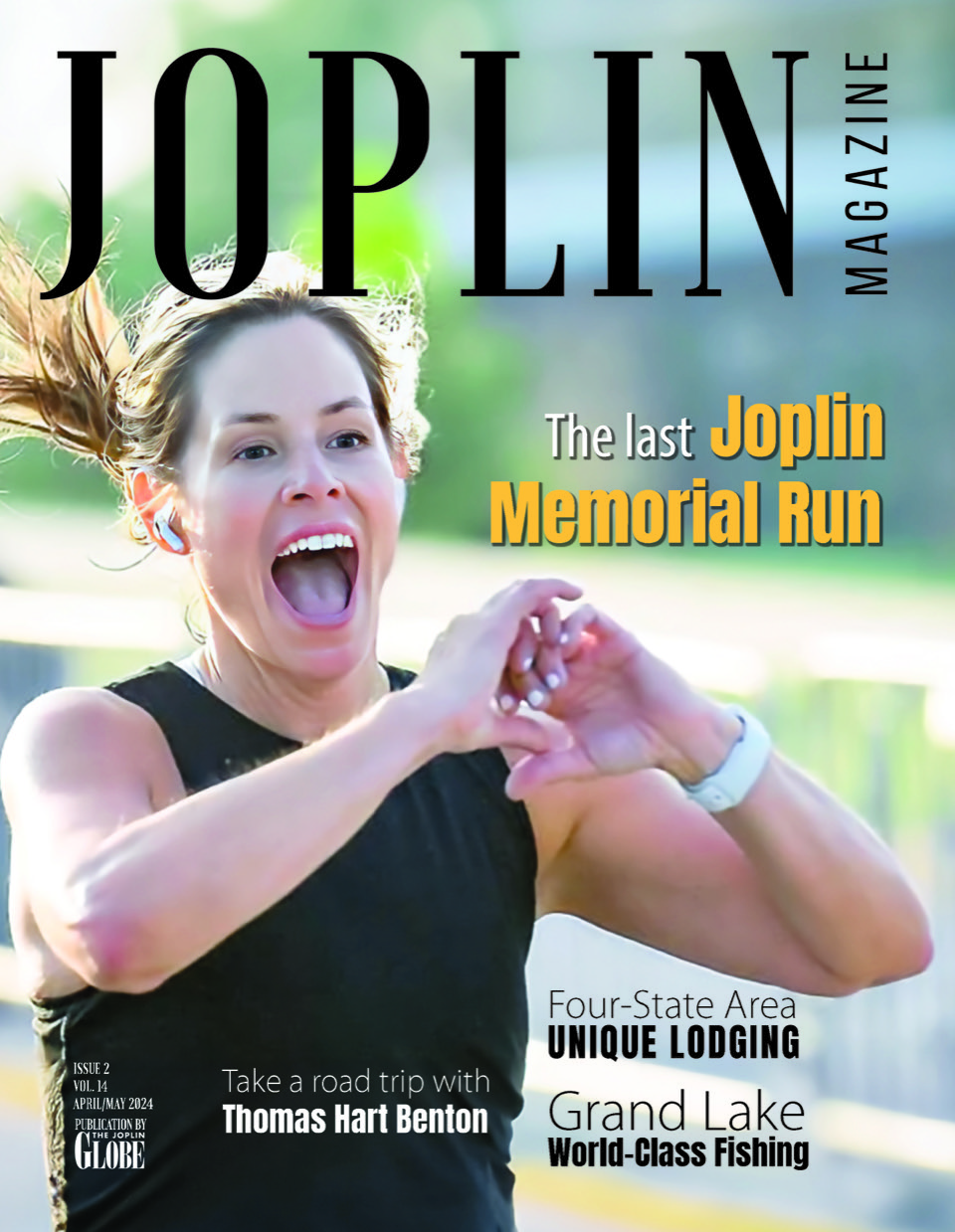

It took weeks for Huddleston to regain her balance and walk comfortably again without a walker. But even before she had accomplished that, she had set her sights on another goal: She wanted to run again. One more time. So in May 2012, she ran the inaugural Joplin Memorial Run 5K in 24:49, placing second in her age group.

Huddleston is excited for her graduation, but she fears it will be more of a remembrance of the 2011 tornado than a celebration of her accomplishments. She also is nervous about being in exactly the same time and place that she was five years ago, remembering the horror that followed then.

Her leg has healed about as well as it ever will. But the emotional healing has been a stop-and-go process.

"A lot of people don't have the daily reminders, but I get dressed every morning and see the scar on my leg," she said. "Sometimes I look at it and say, 'Look how far I've come.' And other times it's a challenge to wonder, 'Why did this happen to me?'"

THE NEW NORMAL

Outside the two-story house at 2316 Kentucky Ave., life appears to have returned to normal.

Inside, there's a new normal.

Tamara Comer and her family were some of the first to return to the disaster area after the storm, beginning construction of a new home in the fall of 2011, moving in that winter. They returned to the same location where they were living when the tornado hit, emerging from the interior closet where they took shelter that Sunday to find their home, their neighborhood, one-third of their town in ruins.

It was eerie returning to her neighborhood in early 2012, she told the Globe soon after moving in. There were no street lights, no trees, no birds or squirrels, no neighbors, none of the ordinary sounds, including traffic and the shrieks and laughter of children.

"It's like you're living out in the country," she said at the time.

Now it's a neighborhood again. There are more than a dozen homes on both sides of her block, with only a couple of empty lots.

"It's built up. The kids are out playing again. The street is busy with cars. There are buses up and down the road," she said.

"It is really just unbelievable," she said from her front porch, thinking back on five years. "Absolutely nothing here."

"Slowly but surely the town is coming back."

But inside 2316 Kentucky Ave., recovery has not been as easy. Comer cannot escape the reminders of just how much has changed, how much was lost. Only three other families who lived on the same street returned, but the rest of her neighbors are new.

"I just miss my old neighborhood," she said. "Even five years later ... it still is a shock to walk out and see the new neighborhood. And all your friends are gone."

Inside, her new home has a storm shelter. Yes, it gives her peace of mind, but it is another reminder of that day. She does not like to think about it, and said she dreads going in there. Her grandchildren have helped decorate it, and friends who helped with the recovery have signed it, but memories of that Sunday five years ago overwhelm even those gestures.

"I don't know what it will be like when I come out, or will it hold, and will I be buried again?" she wondered recently.

Nor will she leave her house today if a storm is coming.

"Before I would venture out and do whatever needed to be done," she said. In fact, she had been running errands earlier that Sunday five years ago.

"Now I am constantly watching the weather channel. I have the weather radio on. I have it (weather) programmed into my phone. I have to use Xanax when storms do come because it just brings that Sunday back."

"You would think that after five years you would be able to get out of bed and not think about it, but it's the first thing you notice, that your house is not the same as it was before, and you say, 'Oh yeah, the tornado.'"

HOUSING RECOVERY

Moving east, toward Range Line, signs of recovery are commonplace, from roofing bundles being delivered at one home to the buzz of power tools filling a recovering neighborhood.

Perhaps no sign is more ubiquitous throughout parts of the disaster zone than the green-and-white ones of Schuber-Mitchell Homes.

On lots from Maiden Lane to Florida, many of them emptied by the storm, Schuber-Mitchell signs read, "Build to Suit." Other lots have homes already on them with signs that say "For Sale."

Crews were framing Schuber-Mitchell homes recently in the 2500 block of Jackson Avenue, and working on homes at the corner of 26th Street and Virginia Avenue, near 18th Street and Michigan Avenue, and elsewhere through the disaster zone.

And on the same day that all this was going on, as if on cue, a Schuber-Mitchell truck rolled by on 26th Street.

Then there's the company's model home at 2915 E. 16th St., and another of its brick homes a block away, where Daman Schuber, one of the principals of the business, talked about the recovery and their role as a home builder.

"In the disaster zone we have probably rebuilt over 100 homes," he said. In all, the company has built about 300 homes in the area since the storm.

"We've got about 65 homes under construction right now in the region," he said.

He estimated they also have 30 or so lots within the disaster zone, many between Maiden Lane and Main Street.

Other builders share similar stories of work done and more underway.

Bolander, manager of planning and community development for Joplin, said there were about 350 empty parcels in the disaster area before the storm. That rose by 1,500 to 1,850, he said, and has since fallen back to 725 parcels today.

Eric Allphin, a contractor from Granby, had crews working on two homes recently along 22nd Street. He said he has built 16 town houses and eight single-family homes in the disaster zone since the tornado.

"I'm building these to rent," he said. "They'll rent the first day I put them on the market.

"I am going to build two more before the end of the year," he added, and then pointed to vacant land nearby that he estimates could accommodate 20 duplexes once he gets it rezoned.

Each of his homes has a storm shelter built beneath the floor of the garage, an area of 35 square feet where family members can huddle during a tornado. He said it adds $5,000 to the cost of the homes.

"I figure a well-spent $5,000," he added.

Private builders were not the only ones to respond. Habitat for Humanity, Rebuild Joplin, Catholic Charities, Salvation Army, Samaritan's Purse and Economic Security Corp. took up the challenge assisting in one way or another in the building of hundreds of new homes for people with limited incomes.

Bryan Wicklund, chief building officer for the city of Joplin, said recently, "We are right at, since the storm, 9,500 residential permits that have been sold at a value of $250 million."

That's all of Joplin, not just the disaster zone, and it includes rebuilds, new roofs, remodels and more. Many, but not all of them, were hit by the tornado.

Of those, 1,647 permits were for new single-family homes, or about 28 per month over the past five years.

"We are very close, five years after the tornado, to having completed one house every day since the tornado," he said.

DUQUESNE

The night of the storm, a mangled strip of vinyl siding was impaled in a tree stripped of its leaves and bark on Duquesne Road. Such sights were everywhere five years ago; today it looks utterly out of place.

One after another, businesses have sprung up in the area, restoring walls that collapsed around the foundations of many homes. These buildings now easily outnumber the few empty lots and bare concrete slabs in the area.

Crackpot Pottery & Art Studio, 3820 E. 20th St., is one of the new businesses to have popped up recently. The fully functioning pottery studio celebrated its first anniversary last month.

"All these buildings were built on existing cement slabs from the tornado," said Brent Skinner, the studio's manager. "So they built the buildings to match the cement slabs to save money. So this little area has turned into a big business area, actually."

While Art Feeds emerged after the storm to help children in the area recover using art therapy, Skinner says his own personal tragedy has shown him adults can also benefit from artistic expression.

"Clay is actually very soothing, it's very addicting," he said. "It's hard to think of other things when you're working with it. I think that's kind of the point; you kind of get lost in your clay. There's a lot of people that come in for different reasons, from tragedies to boredom, maybe even. This is where they come for help."

While the area looks much clearer and the occasional empty slab is difficult to miss — one next door to an office building shared by Keystone Self Storage and Bank of Little Rock Mortgage, 3625 E. 20th St., appears largely untouched since the tornado — businesses in the area said traffic is up compared with pre-tornado levels.

Sydney Doolen, manager of Keystone Self Storage, said: "I think everybody else has built back and I think there's even a lot more businesses that weren't here before. This last year or so it's really caught up. The first couple of years, there weren't a lot of people; I guess they didn't have a lot of stuff to store."

UNTOUCHED CORNER

Five years after the tornado, signs of recovery are everywhere — from the white Tyvek-wrapped homes awaiting siding, to the rainbow of colors that wrap Joplin's spirit tree, still standing amid fast-changing neighborhoods.

But back in that untouched corner, where the tornado had just begun its path through Joplin, the walls of Will Norton's room remain covered in blue and orange graffiti, painted with the number 83 and featuring a football that former NFL athlete Kendall Gammon had once given the teenager.

It's a reminder that the recovery is not over — not for some survivors, and especially not for the families who are missing loved ones.

"You don't really heal from losing your son," Mark Norton said on a breezy day last month at the athletic field that bears Will's name. "That doesn't mean we don't appreciate Joplin getting back on its feet. But from a personal perspective, it's a painful day. May 22, 2016, will be another day where we get up and just try to get through the day."

Commented

Sorry, there are no recent results for popular commented articles.