Let me start by saying that every entrepreneur I know is an addict.

The only thing that separates us from one another is whether we’ve come to terms with our own addiction. Starting companies is hard — everyone has their own war story. Here is mine , about a company I cofounded called Scripted.

I first came to terms with my own addiction in 2006. I was living in LA at the time, and I became obsessed with an idea I couldn’t get out of my head : that I could somehow change the way Hollywood sources screenplays. I became addicted to the idea after a close friend of mine, Zak Freer, kept getting rejected from writing jobs. He was scraping together a few dollars here and there, working odd production jobs. The main reason why he couldn’t make it in Hollywood? He lacked the interpersonal skills it took to get his dream movies made (sorry, Zak, but I think you’d agree with me here). Zak was young, brilliant and the most talented writer I’d ever met. But like so many before him, he was jaded and crushed from rejection after rejection. The only thing that really kept him together was the ounce of remaining hope he had, cheap beer and his family and friends. I wanted to help Zak — that was my mission. We used to go to Gyu-Kaku in Beverly Hills every week for dinner and complain about our respective jobs.

At the time, I was at UCLA in business school. The honest reason why I went to business school ? I wanted a two-year vacation from reality somewhere sunny. When you apply to business school, they make you write essays about what you want to do with your life and why. I may have said something about wanting to be an executive or work in tech, but I honestly had no clue. I applied to Stanford, Harvard and UCLA but managed to convince only UCLA that I had a genuine desire to learn how to be a better manager. With that being said, those two years at UCLA were amazing. During that time, I met my future wife and some of my closest friends, and the faculty, staff and administration at the school were second to none. If you’re hoping to go to business school, I recommend going somewhere warm.

Prior to business school, I was totally lost . I worked in a cubicle at a management-consulting firm called Navigant Consulting. I was in the data and stats group , where we analyzed (what was considered to be at the time) large data sets in hopes of settling our clients’ lawsuits for fewer dollars than they were being sued for, using SAS, Microsoft Access, etc. I was mediocre at my day job, constantly distracted and not really happy. I spent a lot of time day-trading, which is what eventually gave me my initial investment capital in Scripted and paid for business school.

I eventually moved on to another project while I was with Navigant, at the infamous King-Drew Medical Center (a.k.a. “Killer King”) in Watts. It was perhaps the best thing to happen to my career. I met the best bosses I’ve ever had — Kae Robertson, Denise Hartung and Kyoko Matsuba. I learned more from them about how to manage and drive employees in a year than one could possibly learn in a lifetime. Working in Watts for a year on-site with at least one gunshot victim a day coming through the ER really puts things in perspective. It takes you out of your comfort zone and exposes you to what real people have to do to make it day by day—how hard they have to work and the hardships they endure. I was tasked with using data to help make hospital processes better and more efficient . For example, in some cases, individual patients were being blood-tested three times in a single day for the same disease across different departments. We used data to inform hospital employees that this type of thing was going on, and they took corrective action almost immediately. I’d like to think I made an impact by fixing some of that stuff.

Before I was put on the Watts project, I met Ryan Buckley, my eventual cofounder, who worked in the cubicle next to me. Ryan was a hippie, had floppy and unkempt hair, and had crashed the Oscars. I liked him immediately. He and I left Navigant at around the same time in 2006 . He went off to public-policy school at Harvard and met up with me in the summer of 2006 in Europe, where we drank absinthe and brainstormed business ideas (Ryan wrote his own origin story of Scripted here).

OK, so back to my addiction. After I became addicted to my idea, I reconnected with Ryan, who became my counselor. He helped me take my screenwriting idea out of my head and turn it into a practical reality. He introduced me to web-based product development and collaborative storytelling (he was working on a product whereby he could trade stories with his grandfather when they were apart, via the web), and I put two and two together: let’s connect Ryan and Zak and see what happens.

After we all got together, my addiction grew only worse. We came up with so many ideas as the brainstorming continued. The ideas grew, and so did my vision for a company. Collaborative storytelling, screenwriting, disrupting Hollywood : I could see the first writer using our product and winning the Academy Award — all in my head.

I eventually convinced Ryan and Zak that they, too, should be addicted to the mission of this company. They were. We each put $10,000 of money we didn’t have into the company. We started an LLC through a shady website. Our addiction began to cost us real money and real time. Our friends and family wondered what we were doing on calls together at odd hours of the night.

There was just one problem — we had no fucking clue what we were doing.

We were all over the place. Did we have to write a business plan? Did we have to learn how to code? Did we have to meet a bunch of people in the industry? Yes, and we did all of it.

I bought Business Plan Pro software and ran through tutorials on to how to develop a business plan. I wasn’t very good at it and gave up after a few weeks. I thought I could bring myself to take a business-plan writing class at UCLA, but it was too long and cut into the time I could spend on learning how to run the business.

I obsessed over content-management systems — Drupal and Joomla! in particular. To practice, I started an anti-school-administration blog at UCLA called The Anderson Daily, where I wrote long blog posts ripping the administration on minuscule issues, such as why the student cafe was so awful. I actually didn’t care about the cafe ; however, I did care about learning how to custom-code Joomla! templates. I did care about teaching myself HTML, a bit of PHP and a bit of CSS. Adam Altman, one of my closest friends and advisors, taught me everything I know in the early days — just enough to be dangerous, and just enough to know what I would say to a real developer if I wanted to manage a product.

But that was not my strength. My strength was articulating the vision, writing about the vision, getting other people to believe in the mission and marketing the vision to the outside world — in a scalable manner (or “growth guy”, in modern Valley parlance)

But then reality started to sink in. Everyone thought our idea was terrible, and everyone thought we were maniacs.

The first time our idea was shat on was at the Writers Guild of America. A close friend of mine from business school put us in touch with the guild, where we talked about how we wanted to democratize screenwriting by using a web-based tool for writers to collaborate on stories (then have producers source scripts from us). The Writers Guild didn’t laugh; they just told us that there is no way the idea would work, because the guild would effectively crush us.

We weren’t disheartened, though. We thought we had been onto something.

Then we met with our main competitors, Final Draft (they are like the Microsoft of the screenwriting industry — the de facto standard — but the company is absolutely terrible at innovating), and they offered to hire us. They told us we were wasting our time on the idea and that we should do better things with our lives.

But then we started researching more and more and realized we weren’t the only maniacs on the planet who had this idea. A team out of Boston called Zhura — led by Eric MacDonald , an early exec at Sycamore Networks — was trying to solve this same problem from the opposite end of the country. We watched Eric’s progress from afar and loved his product. We were envious of it. He built his first product himself ; we built ours by outsourcing to a Canadian development shop that moved like molasses. Our product sucked compared to Eric’s. The existence of Zhura was at that time the only reminder out there in the world that I hadn’t lost it completely. I wanted to beat Eric, and I wanted to crush Zhura. The problem was that he had $1M, and we had $30K. We were going to have to be scrappy.

Zhura may have mad money, but we had heart, and I wasn’t going to let us lose.

Since we didn’t have a million dollars of our own lying around, I thought a lot about how to gain an advantage. Two things happened . First, the Writers Guild went on strike, which opened up a world of possibilities for independent producers to gain a foothold through new online channels and to gain notoriety. Second , the idea that indie producers should put their stuff started to put their work directly on Netflix and Youtube, new platforms at the time., was exciting .

We took advantage of the confluence of these events in a couple of ways . We put on large events that effectively established us as the subject-matter experts on new media in Southern California. UCLA let us host the events for free, and some big-time names agreed to be on the panel. Alexia Tsotsis, who worked for the LA Weekly at the time, was one of our original panelists.

The second stroke of luck occurred when we added one of the most famed independent producers of all time — Edward Burns — to our advisory board. Eddie is widely considered the godfather of independent production . His producing partner, Aaron Lubin along with his wife , are acquaintances of my sister, Aarthi. They randomly met one day in LA, and she gave Aaron an update on what I was up to. Within two weeks, I met Aaron and Eddie and pitched the vision, and they agreed to get involved. Eddie and Aaron lent us the level of credibility we needed to acquire writers at scale. During the first two years of our launch, when Eddie was heavily involved, the number of creating screenplays using our software grew from 100 to 20,000.

And then we hustled like crazy.

We begged, borrowed, called in favors and did whatever we had to in order to get traction. We worked with Alex Albrecht to buy a screenplay from our platform, and produce it. We managed (thanks to Nate Williams ) to get SPIKE TV to crowdsource a pilot script from us. We even got Jason Calacanis to join us for a panel on the future of start-ups at UCLA back in in 2009.

We hustled until someone offered us our first outside investment check: $50K at a $1.2M pre-money valuation. We were at the Sherman Oaks Galleria, outside the El Torito Grill. We turned down the money because we “had to ask our business partner first.” Dumb move.

The economy collapsed during the fall of ’08 — I packed my bags and left LA

We were totally and completely fucked. The company had no money and no viable ongoing source of income (the crowdsourcing model was just not scalable enough), and we were trying to get a subscription revenue going for a “premium” version of our software. I moved to the Bay Area for a full-time job at Applied Materials and prayed that we could somehow get back on track.

We pitched 100s of investors on our idea, but not a single one was interested.

Eventually, an investor who graduated from one of the early Y Combinator classes, Srini Panguluri (whom I was introduced to by a friend, Nancy Hwang) took a flyer out on us and cut us a check for 15K — friends and family participated in the 100K note (a 30% discount). We paid off our credit cards, but then we started our day jobs.

I’ll never forget the smell of the cubicles inside of Applied Materials the first day I walked in.

They smelled like defeat and made me feel like I was going to be stuck at this place for 20 years and collect a pension (if there was one still waiting for me after that time), and that I was going to be doomed to work at a big company forever. The first few weeks were really hard. I was part of the M&A group, which, at the time, was heavily focused on making solar acquisitions.

But then something magical happened. Because the company was struggling, Applied Materials instituted “mandatory leave” for employees several weeks in alternation. I used the free time to work on the company and gain our momentum back. The mandatory leave cycle went on for 12 months, and the company kept making progress. Premium subscriptions went up, and we ran a few more screenwriting competitions, which were hugely successful. I made it my mission with every off-day I had to fight to make the company my full-time job.

Eventually, Ryan reached out to the CEO of Zhura (at around the end of 2009), and he expressed interest in folding Zhura into Scripted. We absorbed his IP, added him to the board and raised 200K of capital in what seemed to be a very complicated transaction (since it involved 10,000 screenplays generated by 80,000 different writers). My last day at Applied Materials was on February of 2010. I quit, and I’ve never felt better.

The Next Day, Was the Best Day of My Life

I felt free, unencumbered and ready to take on the world. There was no better feeling. I worked with Ryan out of a small venture incubator space called i/o Ventures , run by ashwin navin and paul bragiel. Ashwin and I had been friends in college, and he effectively gave us the space for free.

But eventually, our needs moved beyond i/o — we needed interns. So we hired Dor Rubin and our first “full time” development resource, Josh Palmer (we were previously working with another great developer, Josh Smith, who got us very far). Dor, Josh, Ryan and I worked out of an artists’ loft in the Mission called ActiveSpace , which, at the time, cost $700/month. We continued to grind, trying to figure out whether there was a business that could scale within the screenwriting industry. We felt as if we had been rejected by the LA ecosystem but magically accepted into the San Francisco one because of timing and serendipity.

But the sad reality is, despite the money and the writer-community size of 80,000, and despite making 200K in investments during the last two years there was clearly no path forward in the entertainment industry. None. We connected with Roy Price from Amazon Studios when they were considering pursuing a similar model, but our discussions never went anywhere. The money was almost gone, and we were days away from being out of cash.

Then we got a call from Levi’s. They had heard about us through one of our friends Tyler Willis and were intrigued by our large screenwriter community They wanted to use our writer community to crowdsource a video script for a Dockers ad. That project was a success and completely changed the direction of the company.

We realized where the real opportunity is: we might not be able to change Hollywood, but we’ve amassed the largest writer community on the planet, so let’s sell blog posts and other types of content to businesses.

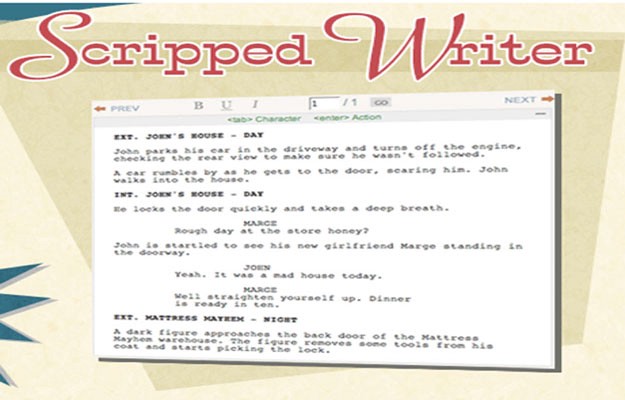

Scripted was the Business

My addiction was back in full swing. I was on calls constantly, hustling and asking my friends if they needed content for their blogs — even asking friends of friends. We learned what the product was by selling it to our friends. Our first product looked a lot like Elance/oDesk , whereby businesses could select their own writers, and we had a rudimentary “credit” system baked in. But what we learned eventually is that businesses hate managing writers and just want a service through which they can press one button and buy exactly what they want. That was Scripted— the name of our new company. Ryan acquired the URL (scripted.com) in exchange for a baseball cap, and we were off to the races. Zak moved on at this point to Harvard Dental School — he is still one of my closest friends and is a dental resident at UCLA. His contributions up until this point in the business cannot be overstated.

Since our product was basically at that point a glorified Excel spreadsheet and a system for e-mailing writers from our screenwriting community, we needed help immediately. We hired Shellie Citron, who was acquainted with a friend of mine, to run accounts. Shellie was amazing. She was the perfect combination of someone who could write impeccably, edit impeccably and was amazing with clients. She joined us without knowing whether we’d have enough money to make next month’s lease payment. Ryan and I told her we were folding the business if we couldn’t get profitable or raise enough money to scale the business. She didn’t care — she believed in us.

The business , run by myself, Ryan and Shellie, started to take off in a major way. So much so that we were able to raise a $1M seed round from Crosslink Capital in the fall of 2011. Vik Gupta, who introduced us to Crosslink, was the first person to really believe that this could work, and Doug Feirstein was the first person who believed it and put money in. But we had absolutely no technological advantage.

Then came Jake. Jake was a “contract” developer who worked with Ryan at Rapleaf. Ryan and I had all sorts of ideas in our heads and could no longer use our fake technical cred to get by. We needed a world-class engineer to translate our crazy product vision into reality. Jake said he could do it in five weeks.

Over the course of those first five weeks, Jake realized — and we realized — that we could work with him for years on this problem. We loved each other. Jake became a brother to Ryan, Shellie and he . He joined us full time in January of 2012. Sara joined us shortly thereafter.

The first Scripted retreat with the five of us in Napa was amazing. Jake had every technical question thought through and nailed down. I had thought through all the marketing ideas and tactics. Shellie and Sara were the best with product ideas to maintain quality at scale. Ryan made the underlying infrastructure work. We were a strong team, a team that was extremely skilled and respected each other to the moon and back. I was still addicted, but now even more so.

The Team Grew — and so did our ambitions.

Our team was a strong, determined bunch: Josh Tobias , whom we met through Craigslist; Eric MacColl, whom I convinced to join the team after he had turned me down three times; Tasia Potasinski, a UVA track star how had e-mailed us through info@scripted; Murad Salahi, who negotiated with me from a playground park bench that wasn’t big enough to hold the two of us; Michael Groenemann , who turned us down once and realized that big companies weren’t for him; and Sylvain Niles, who has the best tattoos I’ve ever seen. As our team grew, their addiction grew along with mine. We were in this together; we were family. In ways, we were all addicted to each other as well, working together long hours and talking almost 24–7 about our ideas, ambitions and visions for this thing we were working on.

Hundreds of companies were outsourcing writing to Scripted, and writers were getting real money every month. We had a guy try to outsource his best-man’s wedding speech to Scripted; we had students trying to outsource term papers (we deleted these projects) ; and we even had VCs outsourcing their thought-leadership pieces to us.

But then we ran into trouble.

By this point (late 2012), the company was pulling in tens of thousands of dollars in monthly revenue, but we knew we needed to fundraise sometime soon. We got to the final stages with three top-tier Sand Hill venture funds. I did a full partner meeting at all three, and one firm even sent their entire partnership to our offices (a strong indication that they may issue a term sheet). None of them converted. The company had four weeks of cash left. It was dire.

You never forget the first time you have an anxiety attack.

It feels like you’re having a heart attack. I had one a year prior . In 2011, I met with one of our rivals (Gary Swart from oDesk, who is now one of my closest friends and mentors), who had just purchased a site that was competing with Scripted. On the same day, I met Dana Brunetti and Kevin Spacey at our offices to try to get them involved with the company. On the way back to my house, after the grueling day, I felt my heart pump irregularly. I was on the 101 far, far away from home. I managed to call my parents and stay on the line until I reached our doctor’s office. It felt like an eternity. When I got there, the doctor checked me out by giving me an EKG and told me that I was totally OK — that it was all in my head and that I would be fine. He gave me a few drugs in the benzodiazepine class in case I needed to relieve anxiety on a situational basis.

After we got rejected by all of these funds and we had almost no money (and I’d likely to have to fire half the staff) — EVERY day was an anxiety provoking event.

The best day and the worst day of my life was the day my first daughter was born, on 11/11/12.

I was so excited for us to have a new member of the family arriving, but my mind was preoccupied with the impending doom of the company. Then she was born — with health complications — and I could not be fully present for her and my wife because I had the job of trying to get the company a lifeline. Without knowing the full extent of the health complications, I walked out of the hospital hours after she was born to take a call with a VC who may have been interested in investing.

I felt like a heel. I couldn’t deliver for my family; I couldn’t deliver for my company; and I had no control over what my daughter faced on the day she was born. I am still traumatized by this, and in many ways, I still haven’t had a chance to process those first three days she was born (during which she went through batteries of tests while I was taking investor calls).

After dozens of calls and meetings, we were saved by Western Technology Investment and Vik Gupta. WTI, a venture debt firm here in the valley, took a look at our business and felt that it was investable and that we needed just another three months of runway to prove out the model. We signed their term sheet for debt, and no one had to get let go before Christmas. I breathed a sigh of relief and hugged my newborn daughter that night while we were on vacation in Irvine.

When we came back in the new year, a few things clicked, and the business once again started taking off. We eventually closed a Series A led by Redpoint (involving great investors like Michael Birch, James Currier, Stan Chudnovsky, Rick Marini and Paige Craig) and Crosslink Capital , who supported our seed round, A round and B round. Crosslink supported me throughout the whole process — in particular, Eric Chin, Omar El-Ayat and Alex Niehenke. The team celebrated the news, and the company grew more and more.

As we continued to grow and I became more obsessed with wanting to succeed and not willing to accept failure, the stakes kept getting higher and higher I felt a personal sense of responsibility to our team and for the writers who were making a living off of our platform. I was proud of the fact that we paid over seven figures to writers in a short period of time.

The Psychological and Physical Toll Were Immense

But under the surface, I walked into work every day wondering , am I an impostor? Did I really just raise all this cash to build this business with this amazing team? Is this a dream, or is this reality?

I later discovered that this is an extremely common theme among young tech CEOs: that your mind doesn’t feel up to speed with what you’ve actually accomplished. I also would go on to discover that most tech CEOs I know suffer from some sort of anxiety disorder. I’ve personally seen CEOs deal with it many ways — drugs, alcohol, pornography addiction, addiction to marathons/CrossFit, overeating, binging on TV to escape reality, traveling all the time to escape reality, etc. We all have a vice, and we all need to medicate in some way. In many ways, I agree with what Chris Sacca says here, around the idea that CEOs generally do experience some psychological issues. Very few CEOs I know are totally “normal.” Most are obsessive-compulsive . A CEO’s energy can be used in either a positive way or in a way that puts us in a very dark, dark place. I’ve seen the dark and the light, and I know most of my friends have too.

You forget the notion of having a “true self.”

One of the hardest things about being a CEO is having to switch context really quickly. One minute you are managing employees; the next you are meeting investors; the next you could be at a conference; and the next you could be pitching a customer. Each of those situations requires a totally different context, and I learned that fast. But by the time you come home, you have so little left for your family and friends, which takes a major toll on you personally.

I like using sports analogies a lot. When you’re a CEO of a start-up company (or a Fortune 500 company), it’s like being a professional athlete. The only difference is that you don’t have an off-season ; you don’t have time to recuperate and physically train for what you face. You are working 24–7, and your body doesn’t have time to recover. There is no “training” for CEOs other than having close friends and a support group to reach out to in your dark days. In my case, I was really lucky to have advisors whom I could lean on, like Vik Gupta, James Currier, Julie Henley, Laurie Yoler, Stan Chudnovksy, Chris Michel, Gary Swart, Don Hutchison, Benjamin Wayne, Semil Shah and numerous others.

The grind continued.

The stakes grew higher and higher. Scripted continued to grow throughout 2013, and the culture remained strong and intact. I was able to convince Jon Miller, the cofounder of Marketo, to join our board of directors. Revenue was growing. We were invited to all the right conferences (including the Fortune conference in Aspen and the Goldman Sachs Private Internet Company Conference in Las Vegas). We even got Kevin Spacey formally involved with the company, and he mentioned us during his keynote speech at Content Marketing World. The company was tight, and our hiring bar was high; and though we were new to introducing the sales function at Scripted, everyone seemed to get along.

Then I made my first bad hire. We needed someone to effectively run the books, do some operational work and manage a wonderful employee we had who had amazing potential. We interviewed a bunch of candidates — the need was urgent. We finally narrowed it down to two. We had concerns about both candidates but ultimately picked one. The concerns we had about him were magnified 10,000 times when he joined. He undermined every employee and every department and took every opportunity to reduce my confidence and that of the others around him. He was a big-company political machine with an agenda of his own , not a start-up hire (despite that, I actually liked him quite a bit personally , as he was a decent guy). Coming into work every day started to become less addicting , and I didn’t want to manage him.

Then I didn’t want to manage the growing tension between sales and customer success. It was unpleasant. “Can’t we all just get along,” I thought? I played intermediary, heard both sides and sent both sides home with the message that they should be adults and figure out how to work together. It turns out that the management style I employed didn’t work for a company that was scaling fast. In the early days, when there were fewer than 20 employees, it was easy to trust folks, because you work with them closely and know what they’re capable of. As you grow, that becomes a lot harder unless you can build out a competent executive team.

It’s the stuff you don’t like (sales operations, in my case) that you have to dig into more to become a better CEO. The result was more anxiety and more conflict because of my bad hire. And then there was another bad hire. Things started to look a bit ugly, and rather than instill energy within me, many of the people I surrounded myself with sucked energy from me. I had been trying to climb up this mountain for several years by this point across two companies. We closed our Series B in November of 2014 from Storm Ventures, with Redpoint and Crosslink participating, but I fell extremely ill after the round closed and was incapacitated for two weeks. I ultimately stepped away from Scripted in January 2015 (before our second daughter was born in March of 2015) and have had a year and change now to reflect on the journey. The story ends abruptly here, but there is obviously a lot more to write.

How to rehab as an ex-CEO

I was fortunate enough when the folks at Foundation Capital brought me on as an Entrepreneur-in-Residence for most of last year. It was the best “recovery” an entrepreneur could ask for. I met dozens of startup companies and worked with amazing partners, including ashu garg and Joanne Chen.

Knowing what I know now, I would definitely be a better CEO. I would dig into the stuff I don’t like to become an expert on it. I’d surround myself with people who support me at every stage of the journey , both in my business and personal life. I’d take care of my body better. I’d deal with anxiety in a healthier way. But I’m not the CEO of Scripted anymore. I will be the CEO of another venture-backed company someday, and when I am, I will be amazing knowing what I know now.

I just took another role at a late-stage venture-backed company called Replicon, where I run marketing. The co-CEOs are amazing, and the board is world class (Chamath Palihapitiya from Social Capital and Jason Green from Emergence Capital). It’s given me the opportunity to really dig into the operations of a business, spread my wings and excel at what I do best. The company is achieving tens of millions in revenue, is profitable (and cash-flow positive) and has a clear path to a very large exit. Being at Replicon for a few months has given me my confidence back and empowered me in a way I can’t describe.

By night, I also run The Bold Italic , a San Francisco online magazine that was previously owned by Gannett Publishing. Reviving it with Sonia Arrison Senkut and turning the site profitable has been an amazing experience. I also write a column for Inc. magazine on weekends, which gives me the opportunity to interview great people within the tech community and to keep my network alive. I am staying busy, and I love it. Most importantly, I am able to spend more time with my family and my daughters — especially our eldest daughter now. I was not a good parent when I was a CEO, and I strive to be better at that every day.

But it’s not perfect. I am still recovering in a lot of ways, and I have hiccups all the time. There are many days and weeks when I still think about Scripted and lament the fact that I was the guy to make this business huge but that I am no longer part of the journey. What if I’d just taken a vacation for a few weeks when I needed to recharge? What if I were still the CEO? What would I do differently, and where would the company be now? The story of Scripted continues, and I am no longer a part of that, which is simultaneously something I am proud of and something I feel wistful about.

But I would do it again, and I will.

Before you become a CEO, you should know how hard this journey is. There is no straight line between starting and success. If you experience early success, I can almost guarantee you it will vanish faster than the blink of an eye. Don’t pat yourself on the back for getting into Y Combinator, getting TechCrunch to write about you or getting external validation, which is fleeting. Pat yourself on the back when you can look around and recognize that everyone you work with is someone whom you’d go to battle with, and vice versa. That’s how you know you are on your way to building something great and something you can feel good about. This is the story of my journey. I hope anyone who reads this will decide to take the journey and also write a story someday about how successful he or she is.

Sunil Rajaraman is the Co-Founder of Scripted.com, CEO of The Bold Italic, and a columnist at Inc.