Prisoners and propaganda: A Red Cross delegate’s view of the Korean War

After the outbreak of the Korean War 70 years ago, a delegate from the Geneva-based International Committee of the Red Cross travelled to the Korean peninsula to try to help victims of the conflict on both sides. This is what he encountered.

“Geneva, June 26, 1950. The International Committee of the Red Cross announced tonight that it had offered its services as mediator to the governments of North and South Korea,” the English-speaking press reported. “The main purpose of his (Frédérick Bieri’s) visit to South Korea is to contact both the North and South and to offer services to them.”

Frédérick Bieri, the ICRC’s delegate based in Hong Kong at the time, collected press clippings such as this one and sent them to ICRC headquarters in Geneva. He was preparing to leave Hong Kong to represent the ICRC in South Korea, which had been plunged into total disarray.

However, the mediation offer was just a rumour. The ICRC’s mandate was to provide humanitarian assistance and protection to interned prisoners and the civilian population. This is what the ICRC had proposed to the North and South Korean authorities, at a time when the two Koreas had not yet signed the Geneva Conventions, which dated mainly from 1949. These treaties were thus very new, even for the signatory states.

As soon as Bieri obtained South Korea’s agreement on June 26, the ICRC at once took the necessary measures. The ICRC’s president, Paul Ruegger, also sent a telegram to the North Korean foreign minister to offer his organisation’s services. But he received no reply.

Jacques de Reynier, appointed ICRC delegate for North Korea, was unable to enter the country. He tried his luck in passing through the USSR. Another delegate, Jean Courvoisier, travelled to Hong Kong to obtain a visa for North Korea. However both failed in their endeavours. Only Bieri was able to enter South Korea, one week after the start of the war. Two months later, de Reynier joined him.

Frédérick Bieri

He was born in London on February 24, 1889.

Bieri, who held Swiss nationality, worked as an ICRC delegate in London, Hong Kong, Tokyo and South Korea between 1944 and the 1960s. He was the ICRC delegate responsible for South Korea from July 1, 1950 to June 30, 1952.

Source: ACICR, B RH 1991.000-075

Arrival in South Korea

Frédérick Bieri was officially appointed ICRC delegate for South Korea on July 1 and arrived in Seoul by plane on July 3. He was immediately received by the South Korean president, Syngman Rhee, who expressed his full agreement with the ICRC’s activities to help the victims of the conflict, just after South Korea agreed to apply the Geneva Conventions of 1949.

Bieri was at first based in both Seoul and Tokyo, but settled in Tokyo one year later. “Tokyo is the centre of all political authorities. It would have been a mistake to stay in Pusan or elsewhere in Korea and try to obtain all the necessary information regarding the procedure,” he wrote on July 10. Japan, under US occupation, was an important hub for getting medical supplies to war victims. Yokota Air Base, the centre of the US forces on the outskirts of Tokyo, was also the command headquarters of the United Nations forces in KoreaExternal link, at that time led by US General Douglas MacArthur.

ICRC activities on the ground

After two months of war there were 17,000 wounded, according to Bieri’s exchanges with Colonel T.W. Yun, a surgeon in the South Korean army. There was a lack of doctors, nurses, medicines and blankets for the approaching winter.

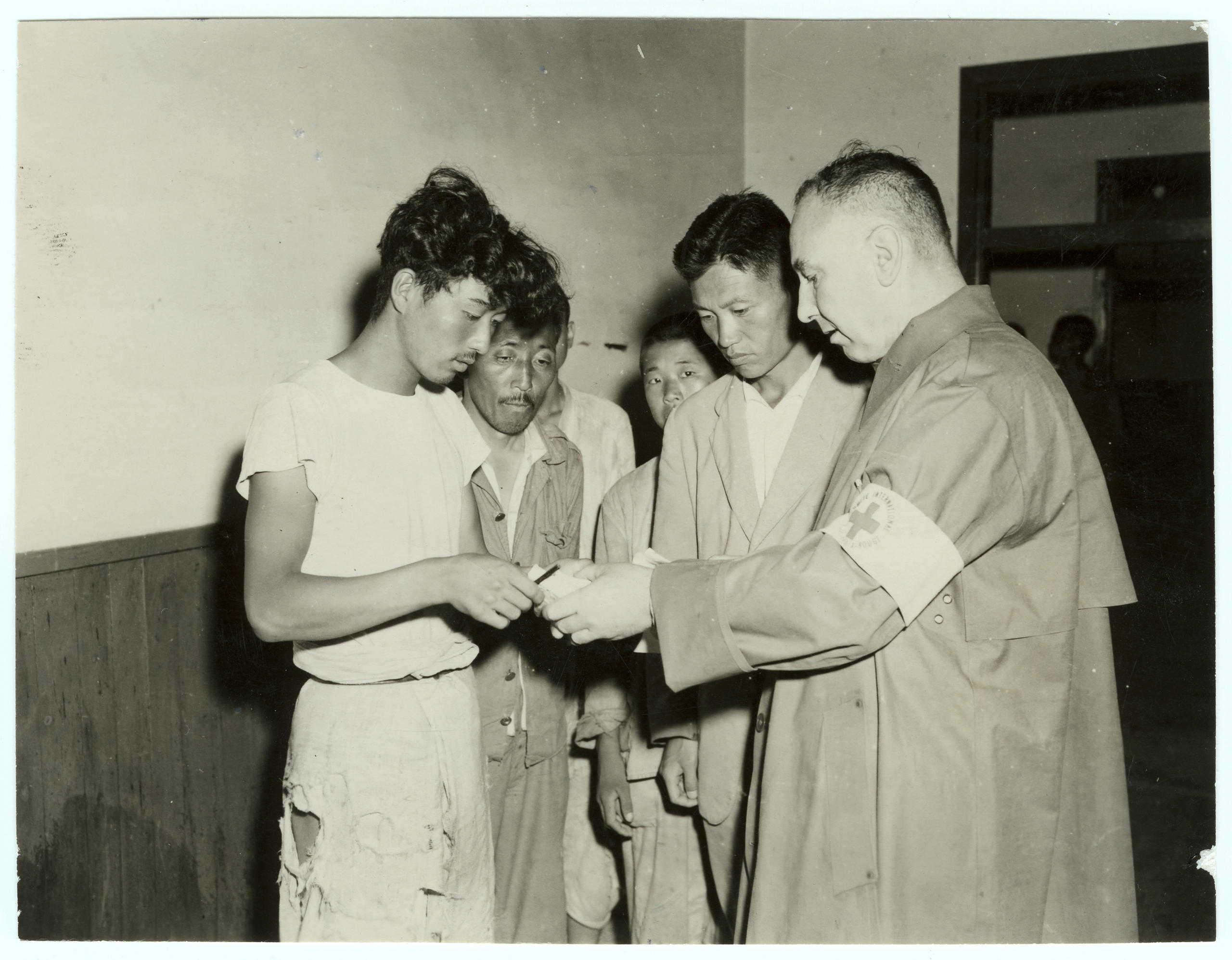

Detailed ICRC reports from August 13 on the condition of prisoners in South Korea also describe the situation in North Korea. After talking to young captured soldiers, most of them aged between 18 and 20, Bieri noted that they had received barely more than a week of military training and one or two weeks of political education. Most of them had gone into battle unarmed. If captured, they were often tortured or killed, he wrote.

The ICRC delegate tried to give them rice, barley or cigarettes.

Bieri also obtained information about POWs in North Korea through airmen and doctors. He wrote, for example, on August 11 that a parade of 150 to 200 American prisoners had taken place on July 22 and that some of them had been carrying an anti-capitalist banner. All of them were in very bad shape. Some looked as if they had been beaten, he reported.

In another report from August 11, Bieri described the situation of the refugees by quoting Yung Tai Pyun, president of the South Korean Red Cross. “There are around 60 families who need to be supported. This costs around US$5 per month per family. This is one-fifth of the actual cost of living, but it keeps them alive.”

A telegram sent by Bieri on August 14 states that there were relatively few POWs, contrary to media reports. On the other hand, the camps were not yet fully organised. There was a lack of living quarters for staff and of space. Transport of supplies was difficult.

Confidential documents and distrust in the media

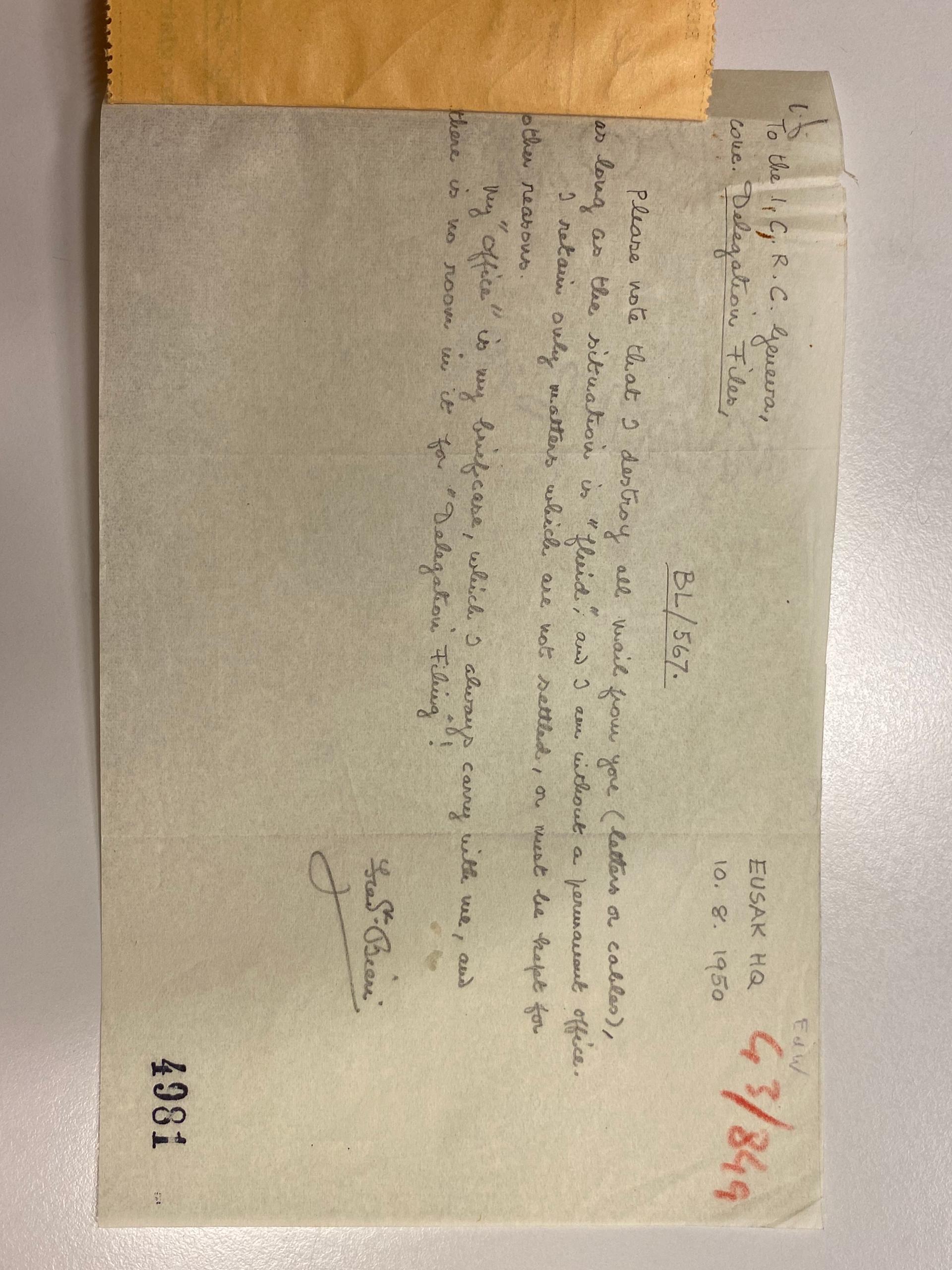

Bieri also informed the ICRC that the situation on the ground was very different from that portrayed by the media. Propaganda was rife. As a precaution, the delegate destroyed any sensitive documents he received.

“All figures published in the press about mass executions should be treated as mere guesswork. I do not think that anybody at all knows exactly what has happened. From what I have heard it appears that both sides were very trigger-happy before hostilities, and happier still afterwards.There is not the slightest doubt about the fact that many people have been disposed of, for political reasons. Massacres of families, however, only seem to have occurred in places occupied by N. Koreans.” (July 21)

Bieri also wrote on August 12 that “a number of broadcasts have been heard here from Seoul, usually at 21.30 until 22.00. These are propaganda talks by a female, who is apparently trying to imitate Tokyo Rose. … the lady in question speaks perfect “American”.”

“Please note that I destroy all mail from you (letters or cables), as long as the situation is ‘fluid’, and I am without a permanent office. I retain only matters which are not settled, or must be kept for other reasons. My ‘office’ is my briefcase, which I always carry with me, and there is no room in it for ‘delegation filing’.

Today, the ICRC’s archives from the Korean War are available for consultation, but a number of documents can not be found, including some of the correspondence received at ICRC headquarters in Geneva.

The ICRC’s archives from 1950 reveal the situation on the ground as described by Frédérick Bieri, Swiss ICRC delegate in South Korea, in particular the living conditions of POWs. The correspondence and telegrams also include communications and decisions sent to Bieri.

Between July 1950 and August 1953, the ICRC carried out more than 160 visits to POW camps in South Korea.

In principle, the ICRC’s archives may be consulted after 50 years, and the records of its decision-making bodies are opened after 70 years. However some documents can not be found.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!