Howard Spira appeared in the Gawker offices one summer day as if summoned from the beyond, which in some sense he had been. He just stood there, anxiously clutching a black plastic bag, his enormous green eyes sweeping the room. His skin had the hue of a life spent mostly indoors and in poor health. His shoulders were bony and hunched. He looked like a broken-down old buzzard.

"What the hell is he doing here?" someone whispered.

Howie had come to talk. He'd arrived from the Bronx, without warning, to discuss his life, the life that had become a crossword puzzle, an entry on "worst in sports" lists, a short passage in another man's long obituary. Or to keep discussing it.

He had already been by to talk a few weeks earlier, with an appointment, showing up wearing a threadbare suit and accompanied by E. Kojo Bentil, Esq., his attorney. Howie Spira, the man who got George Steinbrenner banned from baseball in the 1990s. The gambler turned blackmailer who sold dirt on Dave Winfield. The lowlife behind one of the most shameful moments in Yankees history, and proud of it.

He had the tapes of the phone calls, rattling old Maxell cassettes with the labels numbered in blue ballpoint. And he had stories. About Steinbrenner and escorts, Winfield and a faked death threat. About organized crime: How he was one of the few people in New York to burn the mob over gambling debts and walk away without a limp. He recounted pulpy tales of face-offs with gangsters and near-death encounters. Always more to tell. After two months of talking, Howie would reveal that—just like George Steinbrenner—he had been a valuable FBI asset. It was true. The FBI confirmed Spira had been an informant.

"In your opinion," he asked after I took him into a meeting room, "is there enough here to get a book-and-a-movie deal? Will you do everything in your power to get me a book-and-a-movie deal?"

A book-and-a-movie deal. The question would come up over and over in the coming months, during endless, relentless phone conversations. A book-and-a-movie deal was Howie's salvation from his crummy existence, a state he blamed on other people. His working title: FAME, FORTUNE, AND HELL: The mob-connected gambler who brought down George Steinbrenner. Even before he went to prison in 1991 for extorting Steinbrenner, Howie was telling everyone about how his life should be a book-and-a-movie.

The Spira Files

Howie's cassettes captured his rift with Dave Winfield, his conniving with George Steinbrenner, and his turn against Steinbrenner. They captured threats from the mob. Here's a sampling. More »

Also: Two of Howie's letters, the first to Steinbrenner, the second to this story's author. More »

But now The Boss, the great antagonist to Howie's tragic hero, was gone. A heart attack had carried him off in 2010, eight months after the Yankees had won yet another World Series. Steinbrenner's suspension in the early '90s had given Yankees management a break from his meddling, allowing the franchise to build the core of a new dynasty around its young center fielder, catcher, and shortstop. Howie puckishly took credit for the transformation. Steinbrenner got the championship rings for it, though. The Yankees owner went out of this world as a flawed but triumphant giant, an American success story.

Howie, now 52, got nothing. Not really. No revenge, no final act. He was still there in the Bronx, living in his parents' apartment in a brick mid-rise next to Van Cortlandt Park.

"Why don't you leave the man alone?" his father would say of Steinbrenner.

"He's dead," his mother would sigh.

But Howie couldn't leave Steinbrenner alone. He couldn't leave anything alone. He'd been an obsessive his whole life, especially when it came to sports. As a kid, he made his own multicolored statistical charts for baseball players. He idolized Tom Seaver. When he flipped cards with pals, he never risked Seaver.

That's how his gambling started. Then came the bets: 50 cents, $1, more. In 1975, when he was 16, he walked into a candy shop on Gun Hill Road and handed $110 to Chuckie Manzino, a slim bookie with a pinkie ring: 55 to win 50 on a pair of college games. USC against UCLA was one of them. He can't remember the other. What he remembers is that he won $100. His limbic system lindy-hopped, and that was that.

The thrill lingered, but his luck didn't. Turned out Howie was a natural loser. By 1982, he was into mafia bookies for at least a million dollars, maybe two.

Thirty years later, and Howie was still chancing it. In gambling, a "mind bet" is a fantasy wager you place in your head when you're broke, busted, or "tapioca," as Howie's mob lawyer described it at trial. (Howie later fired the man.) Howie knew all about mind bets. He'd had one going for decades: his book-and-a-movie deal. All or nothing.

I steered Howie to a table near the office entrance, where leftovers from a catered breakfast remained. I suggested he eat. He began cramming cheddar-and-bacon scones into his mouth. Then he attacked the vegan pancakes.

"You can go back to your desk," he said, waving me off between bites. "I'll be fine."

Back at my desk, I watched him eat all the leftover pancakes and move into the kitchen. I could see him rummaging. Howie emerged briefly, swigging from a bottle of juice. He stuffed an object I couldn't identify into his plastic bag. And then he was gone.

* * *

The conventional shorthand for what George Steinbrenner did wrong, in press accounts of the mudslinging-and-extortion scandal, is this: The Yankees owner had an "association with Howard Spira."

It made Spira sound menacing—this known gambler, this criminal element. He was the embodiment of the Yankees owner's dark side: Steinbrenner the Nixon bagman, the convicted-and-pardoned felon. Under questioning in court, Steinbrenner described their relationship in ominous terms. Did Spira "destroy" him? "As far as baseball is concerned, yes," Steinbrenner said. "He did a very good job."

All it took was a telephone. "He gets your phone number, and you're in trouble," Tom French warned me. By then, Howie had two of my numbers.

In the '80s and '90s, French was an FBI supervisory special agent. He headed up investigations into all of New York's five original mafia families and, at one point, ran the bureau's Westchester County office. Associating with Howie was part of his job. He closed out Howie as an informant in 1986, but that didn't stop the phone calls. French retired to do contract work for the bureau, but that still didn't stop the calls. His phone rings, even now, and Howie's squeaky Bronx twang is on the line, spraying information, pleading for help with the book-and-a-movie. French was the only one who could stand him.

"He's a noodge," French said. "Noodge" is Yiddish for "pest," and immediately, Howie bombarded me with calls. But he was so much more than a nuisance. He talked like a Tommy gun with no semi-auto setting. No boundaries. He called to tell me when he was going for a walk. He called to talk about a terrible pain near his "penis area." If I didn't pick up the office phone, he'd call my other number. If I didn't pick that up, he kept calling.

AUDIO: A call from Howie Spira

He hectored me constantly about the story I was writing, demanding to know about run dates, edits, and other issues over which I had no control. "What will you do to promote this?" I didn't know. "Will it come out this week?" I wasn't sure. "Next week?" No clue. "Will it come out during Rosh Hashanah?" Huh? "It would be very bad if it came out then because most of the people with money and power in this country are Jewish, and they won't be paying attention." OK, Howie.

Howie hemorrhaged information about Winfield and Steinbrenner, the mafia, prison, baseball, women, clothes, the weather, his parents, his health. He jumped from one tangent to another, many of them fascinating and relevant, some bizarre, others difficult to fathom. Like the time he told me Winfield held a gun to him. Or the time he said Steinbrenner had sent him a prostitute. Even a hint of incredulity nettled him: "I know what's been told to me in the past 22 years. That I'm the biggest scumbag in the world, that I'm worse than a pedophile, than a terrorist. I've made innumerable mistakes, but the only thing I don't do is lie."

Howie's credibility was shot years ago, after he got in trouble, because of his own associations with hoodlums and racketeers. His storytelling tendencies made reforming his image all but impossible. He manufactured drama and twisted context to suit his purposes. An encounter with a woman on the street became a date. A few dates became an engagement.

It wasn't that he was lying. He just wanted to matter more than he did. "Eighty percent of what he says could be true," French told me. "And 20 percent of it, who knows?"

French was right about the 80 percent. I verified much of what Howie told me through court documents, outside interviews, newspaper reports, and audiotapes. The good info was spot on. He had a memory like a hard drive. He could recall the dates and scores of baseball and football games from 30 years ago, and I was able to create a loose timeline of his life based entirely on when and where he'd been watching games.

But then came the 20 percent. There were anecdotes, a few of them sensational and overly perfect for a book-and-a-movie, that were impossible to confirm—mainly because the other people involved were senile, dead, or unwilling to comment. But the stories were impossible to disprove, too.

Maybe that slippery 20 percent helped explain why Howie had shopped his story for so long without success. Howie attributed his failure to the media's fear of the Yankees and Steinbrenner. The main reason, however, was that Howie could drive a person bonkers.

In person, he was charming and funny, a natural cutup. On the phone, he could turn into a monster—whining, ranting, badgering me about things I had already told him couldn't be answered. In three months, he left me more than 80 voicemails and called at least 200 times. When his number flashed in my caller ID, I experienced panic, followed by dread, followed by a feeling that I can only imagine is similar to being locked inside a crate and dropped to the bottom of the Hudson River.

In the absence of a fulfilling life of his own, Howie hijacked the lives of others. He'd bottled up 30 years of existence and wanted to release it all at once. His desperation was exhausting. "You'll thank me when we hit the jackpot," he kept saying. He had had a dream, he said: the police were arresting him, while I took notes on my computer in the background. "You're doing great, Howie," I had told him in his dream. "This is great for the story."

I didn't tell him I had also dreamed I was at my computer, writing this story. Howie was the one in the background. For once, he didn't say a word. There was only silence. It was the happiest I'd been in weeks. Then my alarm went off. "Fucking hell!" I heard someone scream as I regained consciousness. I realized it was me.

* * *

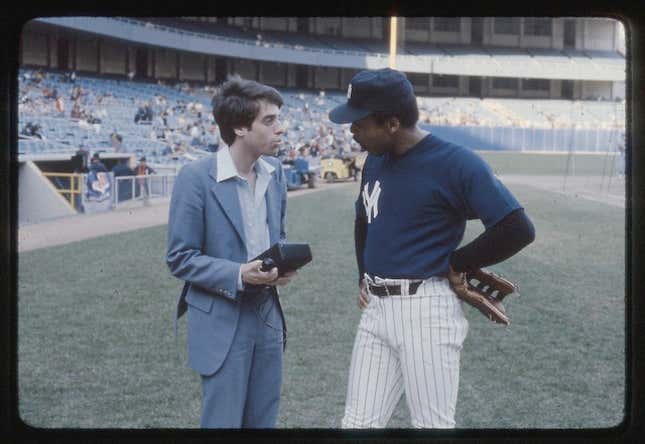

From 1979 into the early '80s, Howie's energies were turned loose in the Yankees clubhouse. Players and staffers, interviewed by Sports Illustrated after Howie became notorious, remembered him as a "green fly," buzzing around. Howie had gone to NYU to study broadcast journalism, scored credentials as a stringer for network radio and wire services, and whirred into locker rooms and press rows across New York: the Giants, the Rangers, the Knicks, the Islanders, the Mets, the Jets. The Yankees, though, were his favorite. He liked baseball more than any other sport and the Yankees more than any other team. But more than sports, he liked feeling important. Being around star athletes made him feel that way. Journalism was a means to an end. Howie figured he'd represent the players one day. Everyone could see that.

"No agents in the clubhouse!" the veteran baseball writer Jack Lang used to shout when he spotted Howie in a sharkskin suit and alligator shoes, sidling up to players. Always dapper then, Howie Spira. He'd grown up scrawny and awkward a few blocks from Yankee Stadium and dressed well to cover his low self-esteem. In the second grade, he wore ties and dress shirts. He played stickball on the corner and ate butterhorns with cottage cheese and sour cream at the kosher deli, chocolate milk to drink, yodels for dessert. Howie was one of the last white kids in P.S. 35. After Good Times came out, his classmates called him the "white J.J." He got a kick out of that. "I was Kid Dyn-o-WHITE!" he crowed.

The mouth on Howie. He had buck teeth. The joke was that if he were on 163rd Street, his teeth would be on 161st. But it was Howie's lip that everybody remembered. You could hear that all the way on Long Island. The kid could talk a dog off a meat truck. But he was also the kind of kid who'd probably let the dog onto the meat truck in the first place.

His father, Sigmund, knocked the hell out of Howie when he was little. The old man was a survivor. Sigmund came from Berlin originally. The Nazis sent him to Auschwitz. He saw his entire immediate family killed. In the camp, he hauled bodies to the ovens. He was only 17 when he made it out, got on a truck and slipped away to Belgium, stayed there until the war was over. When he rolled up his sleeves, the blue numbers on his left forearm glowered. He possessed an uncontrollable rage toward Hitler. Sometimes, he took it out on Howie. He took it out on him with belts and fists and words.

"You're a worthless piece of fucking garbage," he'd yell at Howie in his heavy German accent.

But the old man took Howie to ballgames. He watched pro wrestling with him. After Howie was grown and gambling, some gangsters came to Sigmund's hardware store. Howie owed them a hundred forty-five, they said. They meant 145 large. Sigmund gave them $145 and told them to screw. Years later, when Sigmund got the call that Howie was being arrested, he dashed out of his store so fast that he ran in front of a car and got hit. He got up and kept running until he made it back to the apartment.

"My father really should have worn a condom," Howie said in court. "He did not deserve Howard Spira as a son."

What a lip on Howie. At NYU, he took a class taught by Howard Cosell called "Big Time Sports in Contemporary America." Howie wanted to be another famous mouth like Cosell, but he didn't have the voice for it and he never wanted to do the work. So he paid another student to do it for him. He paid the guy with a couple thousand bucks, a TV, and a fridge. What did Howie care? He was 20 years old and mixing with sports stars. When he dropped out of college in 1980, it didn't surprise anyone.

"There's only one thing I learned at NYU," Howie said. "I was in the men's room. I used to have hair then. Someone told me that if I ran a comb under water there'd be no static. That's the only thing I learned."

Howie preferred to shoot the angles. He used to cruise Yankee Stadium just to find people to ingratiate himself with, to work his rap on. He was always happy when he found a girl. "You're the most beautiful woman I've ever seen," he told Beverly Jackson. That's what Howie usually said, and it usually worked.

Soon he was dining with Beverly's brother, Reggie. Howie complained about his money troubles. Howie had been losing bets all over town. He often huddled over the Daily News sports pages, he said, picking games with Yankees players before calling in wagers on the pay phone outside the Yankees locker room. "I'd bet football with Lou Piniella and Bobby Murcer," Howie said. (Piniella has denied it. Murcer died in 2008.)

"Eat your food and relax," Reggie said. "I'll hit a home run for you tomorrow."

The next day, Reggie belted one. Howie was in the auxiliary press box near George Steinbrenner when it happened. Steinbrenner gave him a hug. That's how they first met.

* * *

Howie recognized opportunity when it arrived in 1981, from the San Diego Padres. Dave Winfield was a four-time All-Star, a two-time Gold Glove winner, and one of the best athletes on the planet—drafted out of college in 1973 by pro teams in three sports. Howie had introduced himself to Winfield a year earlier when the Padres were in town to play the Mets. A few months later, the Yankees inked the outfielder to the richest contract in baseball—$23 million over 10 years—and Howie started in with the blandishments.

"I was focused on Dave like a horse with blinders," he said. "He was going to be the wealthiest, most powerful ballplayer, and I made up my mind that that was the place for me."

Howie sent a dozen long-stemmed roses to the secretary at Winfield's charity. The flowers were Howie's calling card. When he played at journalism, he sent roses to almost every girl who worked for the Mets. Hit on most of them, too. Winfield's secretary agreed to go on a date. "We had dinner," Howie said. "And she was the dinner." (I asked for clarification. "She let me eat her pussy," he said.)

The secretary introduced Howie to Al Frohman, Winfield's squat chain-smoking agent. "Are you one of them radio men?" Frohman asked Howie between nitroglycerin pills. The obese Frohman gobbled the pills constantly for his heart condition. Rick Reilly once described the agent as "10 pounds of Malt-O-Meal stuffed into a five-pound bag. … Frohman ate badly, blew his stack readily and had had his tact removed surgically."

During the Winfield negotiations, the agent wedged a cost-of-living escalator into the already lavish contract, forcing Steinbrenner to fork over more money than he'd expected. Having his star player's salary tied to the Consumer Price Index enraged the Yankees owner.

Howie, on the other hand, liked Frohman. The agent fancied himself old-school Jewish mafia. He talked sharp, gambled hard, and employed a driver who'd done time for bookmaking and who still palled around with Genovese gangsters. Frohman and Howie had a lot in common.

But Howie's real break came on Rosh Hashanah in 1981, when Frohman's heart seized up. Every day for a week, Howie cabbed to Hackensack to visit the fat man in the hospital. By the 1981 playoffs, the noodge had buzzed his way into Winfield's crew.

The idea—at least in Howie's mind—was that he'd help with publicity for Winfield and his eponymous charity, which aids underprivileged children. The other idea–also in Howie's mind—was that he'd hitch a ride to Easy Street. To hobnob with Winfield, Howie felt he had to live like Winfield. He used borrowed money to add 15 suits and a tuxedo to his wardrobe. One day, he surprised his former math teacher at the Bronx High School of Science by picking her up in a limo. That's how Howie got around back then.

He tried to cover his expenses by betting more on baseball, football, basketball, anything. He gambled on credit. Every bookie in New York knew he was with Winfield. "In a way, I put him up for collateral," Howie said.

His debts mushroomed. At night, his phone would ring, voices growling on the other end: "We're on the Long Island expressway. We're coming to the Bronx to kill you." Howie tried to sound tough. He once called back to see if the killers were delayed by traffic. In truth, he was terrified. He lived with his parents, who'd moved to the northern reaches of the Bronx. They installed a three-inch steel bar across their door.

Frohman and Winfield knew about Howie's gambling. Frohman gave him money. So did Winfield. The outfielder loaned him $15,000 or more. According to Howie, the vig was more exorbitant than a regular shark's. Howie blew it all.

He should have realized flacking for Winfield was a rotten deal when Frohman refused to pay him for his work. (The Daily News reported Howie's hiring as a publicist, but Winfield and his lawyer said later that Howie was never an actual employee.) Or when he heard Frohman talk about fudging the charity's finances. Or on the flight back from Los Angeles during the 1981 World Series. The Yankees were losing to the Dodgers, and Winfield was in an awful slump. His only hit came in Game 5—a bloop single—after which he'd called time to ask for the ball.

Steinbrenner was apoplectic and trashed his outfielder in the papers. He'd wanted to

dump Winfield ever since the Yankees inked his pricey contract. On the plane to New York, Frohman came up with a devious plan to protect Winfield: a fake death threat. He ordered Howie to cooperate.

"If you don't do this," Frohman said, "I'll make sure every gangster will know how to get you."

The next day, according to Howie, Frohman fished out a postmarked envelope from the fan mail. He replaced the letter inside with one that he'd written: "Nigger, if you play tonight, you are going to be shot and killed right on the field." Frohman sent Howie to release the threat to the media.

After the news broke, a frightened Winfield raced into the charity offices in New Jersey. Frohman revealed the hoax to him.

"Why?" Winfield said, in Howie's recounting.

"Because you can't fucking hit."

"You go along with this?" Winfield said, turning to Howie. "I should hang you both out the window."

Yeah, Howie'd gone along with it. Not that it mattered much after the Dodgers finished off the Yankees in Game 6. But Howie went along with whatever would help him.

Problem was, he couldn't help himself. He couldn't quit gambling. On Jan. 10, 1982, he bottomed out. He lost $75,000 on the AFC championship game between the Bengals and the Chargers. The same day, he laid out more than $150,000 on Dallas to beat the 49ers in the NFC championship game. Howie was in Frohman's house in California when he saw Joe Montana hit Dwight Clark in the end zone: "Right there, I wanted to die. Every time I see The Catch, I feel sick."

Howie spent most of 1982 holed up in his apartment, the steel bar wedged in place. When he resurfaced the following year to resume his work with the foundation, Winfield demanded his loan money back. "That's when Dave pointed the gun at me," Howie said. Well, Howie remembers it that way. Winfield didn't return messages asking about the incident. I did speak briefly with him earlier in my reporting. He had no interest in talking about Howie.

"There's really no benefit in even commenting," Winfield said. "It's like dealing with somebody with fleas."

* * *

Howie tasted his cherry Coke and frowned. Not enough cherry syrup. He'd ordered 70 percent syrup and 30 percent Coke, which made the young waitress giggle. She was flirting with him. When he asked her name, she directed his gaze to the nametag affixed to her generous bosom, smiled, and invited him to karaoke night at the restaurant that Friday. Howie asked the waitress for an extra side of cherry syrup. She brought it out, along with a saucer of maraschino cherries, which she placed on the table instead of in his glass. "I didn't know if I should touch them," she said.

"It's the Bronx," Howie said and dumped all the cherries into his soda.

Howie could sure make an impression. In Butner Federal Correctional Institution in North Carolina, he used to take off his shirt to exercise. He was built like a mole rat, and he knew it. "You've never seen a body like this," he'd tell the killers on the yard. "Only in science class," they'd retort.

Since prison, Howie had done little to rehabilitate his life. He was too fixated on the book-and-a-movie. He hadn't found a real job or a healthy romantic relationship. Every attempt at love had ended badly for him. When Howie called our waitress at the restaurant afterward, to ask about a date, she said she had a boyfriend and declined.

Here was the flip side to the bold trickster, to the history-making hero: Pathetic Howie. If he'd wounded Steinbrenner, the Boss had crippled him. His life was a shambles. He wallowed in sadness. Lately, he'd been complaining about a burning pain in his stomach.

Howie viewed rejection as a fait accompli. Before he went to jail, he'd only ever dated women who were impressed by his money, and now he was broke. He'd gone seven years without a woman. He had worked it into his patter. "I'd be so happy if I get an STD," he said. "It means I've had sex."

Not long after we'd first met, Howie described the neighborhood around the Gawker office as a "supermodel paradise" and asked me if I could fix him up with "girls in their 20s or 30s, preferably white or Spanish." (I told him no.)

His mother chided him for such romantic partialities. "I don't want you going to the different corners looking for girls because that doesn't work out," she said. "You need something more intellectual. Go to synagogues. Go to libraries."

Howie refused to listen. He still traversed the Manhattan streets in search of beautiful young things. He could talk to girls, no doubt. He carried strips of paper on which he'd printed his phone number in advance, the better to lubricate his seductions. During my reporting, he claimed to have gotten the number for Courtney Roskop, a porn star who'd partied with Charlie Sheen. He showed me her name on his caller ID and shrugged. Roskop had already disconnected her number. I didn't know how Howie could have faked the call without a computer or phone phreaking skills (neither of which was in evidence). But that wasn't the point. The point was that Howie knew that even a drug-addled porn star might Google him and peg him as a scumbag.

He'd been in love a few years back with a pretty Dominican girl named Arlene, who was half his age and seemed OK with his background. He wrote her poems and told everyone they were engaged. Arlene told me they hadn't been, although Howie had asked enough. She knew he loved her. Howie bought her flowers all the time. But he was too much. One day, Arlene told him to skip the flowers and give her the money instead. That broke Howie's heart.

In 2008, he briefly helped with publicity for a small modeling agency but never got paid. That was also the last time he'd been in the regular company of women who weren't his mother. At the agency, Howie made friends with Jana Mináriková, a cover girl for the Slovakian edition of Playboy. Mináriková was kind to him. She once bought him lunch, which stunned Howie.

"He said nothing like that ever happened to him," Mináriková told me. "Meaning that he was never treated by a beautiful woman to lunch."

It took a while for Howie to introduce me to Pathetic Howie. We had to get in a fight first. Howie snapped at me for not devoting more time to him. I snapped back and told him not to ask me for girls. He grew despondent.

"I was waiting for you to throw this in my face," he said. "I came to you. I wanted to use the word friend or acquaintance or whatever. I said, 'May I be completely open and honest with you?' And you said, 'Yes,' and the first opportunity you have, you throw it back at me. Somebody's vulnerability. I'm looking for some kind of a relationship. I don't have to apologize to you for that. I didn't ask for you to pay me with a girl."

I then accused Howie of stealing from the office kitchen. He flipped out and denied it. "Whatever people think they saw, they didn't see it! It was cold, oily food! How am I gonna take it? It was like old, cold pancakes!" I let it go. Howie eventually calmed down."Every time I think I have a chance, something happens," he grumbled.

Only then did Howie begin to open up, as if he couldn't be fully, or truly, present unless in conflict.

* * *

Another story, as Howie told it to me: A spring morning in 1983, and Howie's riding up Third Avenue in a limousine, his head jammed out the sunroof, the roof panel clamped on his neck.

Below him, inside the limo, was Joe Caridi, a granite-faced man who ran sports books for the Lucchese and Colombo families. Caridi was on his way to becoming Lucchese consigliere, a position the FBI says he holds today. Back then, Howie owed him $57,100.

Howie had gotten into the limo outside P.J. Clarke's in Midtown, one of Sinatra's old joints, bearing peace offerings: a baseball and a photo, both autographed by Winfield. But you paid Joe C. in dollars, not baseballs.

"Where's the money?" Caridi said, swatting aside the memorabilia.

"I'm a little short, Joey."

"I hope it's the hundred."

"I think I could borrow the hundred. But I can't get you the 57,000."

Caridi's face purpled with anger. He seized Howie by the throat and shoved his head through the open sunroof. The limo began rolling uptown.

"Reel me in, Joey!" Howie sputtered. "We can work this out!"

In 1990, two anonymous sources "familiar with Colombo family operations" had described the same limousine incident to Sports Illustrated. Howie told me how things unfolded after that. He and Caridi worked it out, sure enough. Howie would pay back his debt, with $700 a week in interest on top. Pay it or die. Caridi yanked Howie back into the limo, tearing his favorite tie, a red-and-blue silk number. That ticked off Howie. Nobody, not even racketeers, banged up his duds. "That's my best tie!" he screamed. "I'm not giving you nothing!"

"Fine," Caridi said. "Let's just go to the cemetery."

Howie kept yelling. He demanded that Caridi replace his neckwear. The mobster played along. He found it funny and took Howie to a tie store. "He needs to look good in his casket," Caridi told the clerk. After that, Howie demanded a burger. "It's his last meal," Caridi told the waitress. When they finished eating, Howie wanted $50 for cab fare. Caridi was really laughing now. He peeled off the cash. "I'm going to bury you with this fifty," he said, or something like that.

The next day, Howie showed up in Caridi's club. He brought a list of all the people he owed money to so Caridi could protect him while he worked off his debt. It was a long list.

"What the fuck is this, the kosher Yellow Pages?" said Louis "Louie Electric" DeCicco, one of Caridi's men, who would later become a capo in the Bonnano family. "It would be so much easier to kill him."

"Nah," Caridi said, flicking his gold lighter. "I find him amusing."

Caridi smacked Howie around a little then, especially when the club served lunch and Howie didn't know how to twirl his spaghetti like an Italian. Howie was always getting smacked. Didn't mean he enjoyed it. He hissed at Caridi over his noodles. "You know, I'm beginning not to like you."

The mobsters in the club clammed up. People got clipped for less. Caridi leaned close to Howie. "I have to pay you a compliment," he said. "You have more balls than most made guys I know."

* * *

Howie was waiting for me on Broadway outside the Major League Baseball Fan Cave. It was late September, and he had on his old suit, the one so worn that patches of it glimmered in the sun. MLB commissioned the Cave, a multi-story catastrophe of flat-screen TVs and cow-skin rugs, so two fans could sit inside watching all 2,430 regular season games plus every postseason game in 2011 while slowly going crazy. Through the windows, the Cave dwellers looked like rats resigned to electric shock.

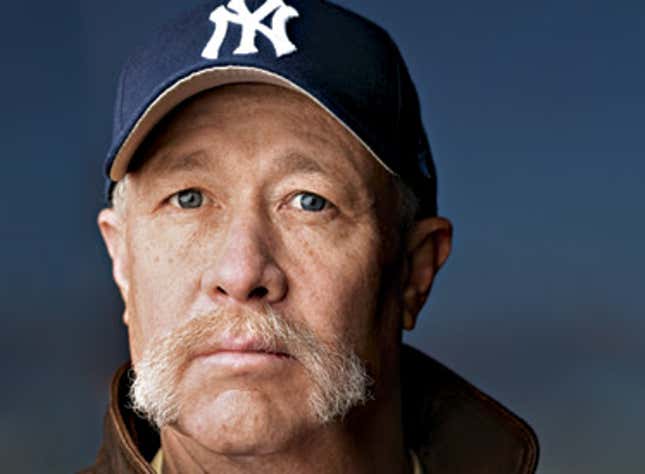

Goose Gossage was visiting the Cave today. He'd come for a launch party for a set of Yankees tribute DVDs called Yankeeography: Pinstripe Legends. The videos were mini-documentaries on Yankees players, including Winfield. I'd been invited to the launch and asked Howie to come. He'd refused at first. He'd been pissing blood for weeks. Also, he hated Goose Gossage.

"That redneck motherfucker," Howie said. "He'll probably attack me."

But Howie changed his mind at the last minute and moved his doctors' appointments. Anything for the book-and-a-movie, which I'd come to imagine as What Makes Sammy Run? meets Goodfellas with a dash of the Coen brothers (or perhaps the Zucker brothers). I added a guest to my RSVP. When questioned about his identity, I said he was a work associate. We passed through security with ease.

Salespeople, advertising executives, and MLB employees had gathered on the lower level of the Cave. Howie made for the food. "Good pizza," he said, munching away.

I told him it was focaccia. He looked puzzled. All his years with Italians, and he'd never heard of focaccia. He transitioned to some bite-size filet mignon burgers that he called "Lil' Whoppers." At that point a guest at the party asked him how he'd come to be in the cave.

"I had an association with George Steinbrenner," Howie said.

"What kind of association?"

"It's complicated."

"Tell me more."

"I got George Steinbrenner thrown out of baseball."

The guest left Howie alone after that. Howie leaned against a sofa. Behind him, images of Winfield from the DVDs played on a screen. Howie began to mutter dark things about getting screwed and closure. Only death, he said, would set him free. "I want to die," he said. "I'm happy to die."

It was around then that the two Cave dwellers approached to talk baseball. Howie asked if they knew about Steinbrenner's ban. They barely did, which annoyed him.

"Which team do you follow?" he asked one cave dweller.

"I'm a Yankees fan."

Howie sneered. "Oh, I thought you might be a historian."

Then he asked the other Cave dweller when Kirk Gibson had hit a World Series-clinching home run. The Cave dweller thought of 1988, the pinch-hit shot for the Dodgers. But that was only Game 1. Howie meant 1984, Game 5, Gibson's Tigers against the Padres. It was only the eighth inning, and the Tigers were already up a run. But Gibson hit that one off Gossage.

"Average sports fans who don't know anything," Howie grumbled after the Cave dwellers left. "My story was the biggest in the world and they'd never heard of it."

He had his vinegar up now and crossed the room to hit on a 5-foot-10-inch former Ford model in heels who towered over him. Howie wanted to know if her diamond ring was real. (It wasn't.) Before long, he had her laughing. When I got closer, I could hear that Howie was talking about Gossage, who was posing for photos about 20 feet away.

"He's like the bad Walton," Howie said. "He reminds me of exactly what I was in jail with in West Virginia: an ignorant redneck chewing tobacco with his one tooth."

Howie said Gossage threatened him once in the clubhouse. At the time, Howie was friendly with mob figures, and he let Gossage know it. Goose shut up. At least that's how Howie told it to the former model a few minutes before he slipped her his number.

But he wasn't done. On his way out, he buttonholed the senior manager of programming at MLB Productions. "You ever see the commissioner?" Howie asked curtly. He was halfway up the stairs and backlit and he loomed over the MLB man like a malevolent wraith. "There's a very big story about me coming out. I'd like the commissioner to read it." The MLB executive looked bewildered.

"Do you know who I am?" Howie said. The executive confessed that he did not.

"I'm the guy who got George Steinbrenner thrown out of baseball."

With that, Howie buzzed up the stairs and out of the Cave and all the way back to the Bronx, where his neighbors still whisper when they see him on the street. A week later, he called in hysterics to tell me he had stomach cancer. Of course, he didn't know if he actually had stomach cancer. The doctors only wanted to test him for it.

* * *

As the 1983 baseball season progressed, Howie became increasingly involved with the mob. His balls impressed Caridi, but his associations made him useful. Anyone close to pro athletes was someone to keep around.

Caridi had a restaurant named Laina's on Long Island that he'd "acquired" from a debtor, according to Howie. "You and your pretty little suits," Caridi told Howie. "You look like the owner. You're going to run it." So Howie did. He paid bills and ordered supplies. He taught the bartender to make egg creams: chocolate syrup, milk, and seltzer. Every day, he sipped his egg creams at the bar. "Kosher juice" the mobsters called it.

He was still gambling, obsessively and erratically. He could bet both sides of a game and lose twice. Howie had money on the Royals in the Pine Tar Game. George Brett homered in the top of the ninth to give them the lead, but Yankees manager Billy Martin got the umpires to disallow the home run because of excess pine tar on Brett's bat. Howie lost that bet. A month later, after a successful protest by the Royals, MLB ordered the home run reinstated and the game restarted at that point. This time, Howie bet the Yankees. He lost again. Caridi couldn't believe it. "This motherfucking Jew could fuck up a wet dream," he said. Caridi ordered Howie to stick to mind bets: "You got no mind, so you got nothing to lose."

Howie's work for Winfield ended on Thanksgiving 1983. He spent most of his time now at Laina's, where he met the daughter of Colombo underboss Sonny Franzese. She stuck her tongue down his throat. Soon, he was helping with Colombo bookmaking and running Caridi's gambling operation. He took action in the wire rooms over four phones.

He also started stealing from Caridi. Howie knew the combination to the restaurant safe. Each week, he opened it and pinched his $700 interest payment. He also started altering gambling tickets, sneaking into a wire room owned by a former professional wrestler called the "Hebrew Hercules," a man famed for his two-footed dropkick. Caridi's runners would collect from losing bettors, and then Howie would change the tickets so they looked like winners. Caridi would pay the runners what he thought the gamblers had won, and Howie and the runners would split the dough.

"I'm surprised he didn't get multiple severe beatings if not killed over the course of what he pulled," said Howie's FBI handler, a retired special agent who requested anonymity.

That was Howie's newest angle. The FBI had summoned him into its Queens office near the end of 1983. He strolled in wearing a blue pinstripe suit and a camelhair overcoat. On his arm was a beautiful blonde with a cocaine habit. "Look at this little jerk," Tom French thought.

French and his colleagues were tracking Caridi and Franzese. They wanted to know where Howie fit in. Would he be a confidential informant? Sure. Howie needed protection and money. The feds showed him a list of names. "I'll get 'em all," Howie said.

Maybe not all, but Howie produced. His information furthered several successful investigations, according to the FBI. The bureau paid him well, better than many other informants. The agents knew the money went straight to the bookies. Howie was an addict. Unfortunately, he was also hooked on yapping. Once he started, he couldn't stop.

"He about drove me nuts because he would call so many times a day," his handler said. "He provided me so much information that it was hard to keep up with the paperwork."

Howie kept running his mouth and kept gambling. Multiple times, the FBI had to spirit him out of his apartment building to escape his creditors. After Howie got arrested during a raid in 1985, Caridi and his boys threw him a party, said he popped his cherry, and called him Meyer Lansky. But Howie got off too easy. It was suspicious. The mobsters became tight-mouthed around him, his information dried up, and in 1986, the FBI closed him out.

Howie wasn't built to play wiseguy. When he tried to muscle people on the phone, he sounded cartoonish. In one court transcript from a wiretap of his phone, he might have been reading dialogue from a bad screenplay:

"That's a real pretty swimming pool, right, that you have. … Maybe someone'll take a swim. Funny things happen. Now are you paying this money back? … Me, nobody shorts a dime. … See, you don't know who I am. You really don't know. You don't wanna know. I mean, I've never talked so nice in my life. … Now, do you wanna pay the money or what? Cause if I get hot, you'll wish for the rest of what's left of your life, the hour that's left of it, that I wouldn't. Now do you wanna pay the money, my man, or what? Talk. … I'm trying to be cool with you, baby. … I'm trying to be nice. I'm rapping your language. I'd rather put a bullet through your fucking head. … I just hit my hand on the table. I hope I didn't break it 'cause if I broke it, I'll take thirteen fingers out of your family to make even."

Scarier-sounding threats were coming in the other direction. On one of Howie's cassettes, a compilation of his recorded phone calls, a mobster orders Howie to pay a debt and threatens to show up on his doorstep:

"You got money, you little cocksucker, and I'm going to kick it out of your ass. Do you understand me?"

"I have money?"

"Yeah."

"Oh yeah? Could I tell you something? I swear by all that's holy I have two singles in my pocket."

"I don't give a fuck what you swear on, you little piece of shit. You come up with some fucking money or I'm going to kick your fucking ass. I'm telling you. Now do you understand that? Is that plain as day to ya?"

AUDIO: A mobster threatens Howie

The next phone call on the tape is from the end of 1986. Howie had called Winfield, with his recorder running. The two hadn't spoken in years. Howie wanted another job with Winfield, another shot.

Winfield didn't want to hear it. "You're almost begging," he said. "I'm gonna hang up on your ass in a minute."

"Don't bother," Howie said and hung up first.

AUDIO: Howie begs Winfield for another chance

The call after that, a day later, was to George Steinbrenner. Over the soft analog hum of the tape, you hear Howie clear his throat and call Steinbrenner. You hear Steinbrenner answer, his familiar, strident voice sounding even more adenoidal through the phone and Howie's recording device. It was no secret that Steinbrenner still wanted to rid himself of Winfield and his contract.

"I have what you need," Howie said.

AUDIO: Steinbrenner wants the dirt on Winfield

Steinbrenner wanted to meet. French advised against it. "Kid, stay away from that guy," he said. "You're out of your league now, and you're going to get squashed like a fly."

For all his talking, Howie never listened much.

* * *

Tampa seemed pretty nice to Howie. A person could pick a worse place than Tampa to make a fresh start. It was two days before New Year's Eve in 1986, and the weather was perfect. A balmy breeze. A sliver of moon in the night sky.

From his room in the Bay Harbor Inn, Howie could see the lights of the city sparkling. Steinbrenner owned the hotel, which was near the offices of the American Ship Building Company, the business Steinbrenner inherited from his father and would shepherd into bankruptcy in 1993. Howie was scheduled to meet the Yankees owner at the AmShip offices the following afternoon. He didn't expect to hear a knock at his door. Not at this hour. But someone was knocking.

Howie opened the door. This is how he told the story: In the hallway was a stunning woman in a miniskirt, haltertop, and thigh-high stiletto boots. She handed Howie her card: Donna, International Hostesses.

"I'm a gift from Mr. Steinbrenner," she said. "I'm here to fuck you and suck the cum out of your cock."

The next day, Howie strolled into Steinbrenner's office. "Was last night OK?" Steinbrenner asked. His manner was winking, as it would be in such a scene. Howie, the protagonist, responded with a grin and a double thumbs-up.

The phone rang. It was Peter Ueberroth, the MLB commissioner at the time. He told Steinbrenner that Mets pitcher Dwight Gooden was having drug problems. Two weeks earlier, Gooden had been arrested in Tampa for fighting with police. Steinbrenner thanked Ueberroth for the update and put down the phone. He turned his attention to Howie and the more pressing matter at hand: Dave Winfield.

"Just talk," Steinbrenner said.

Howie made it quick. He said he needed cash from Steinbrenner to appease the mob. In exchange, he'd give Steinbrenner the dope about the World Series death threats and the funny business at Winfield's foundation. Steinbrenner was intrigued. The foundation was one of the things he'd tangled with Winfield over. The outfielder's deal with the Yankees required Steinbrenner to make an annual donation of $300,000 to the charity, yet another of the concessions that rankled the owner.

"What are you looking for?" Steinbrenner said.

Howie wanted $150,000, a room at the hotel, a job, and a personal trainer. He wanted to start over in Tampa. Steinbrenner agreed to help, according to Howie.

"Just make sure you hold up your end," Steinbrenner said.

"You don't have to worry about me," Howie said. "Just make sure you hold up your end."

Steinbrenner buzzed an angular man into the room. This was Phil McNiff, the former head of the FBI's Tampa office and now Steinbrenner's troubleshooter and all-purpose security honcho. Steinbrenner had been convicted of making illegal contributions to Nixon—Ronald Reagan would pardon him in 1989, thanks in part to McNiff's influence—but still he had an affinity for G-men. His affinity with the Tampa office, in particular, was so close it would eventually prompt an FBI internal investigation. Steinbrenner gave FBI agents special rates at the Bay Harbor Inn, feted them at cocktail parties and football games, and aided them with anti-Soviet intelligence operations.

Over the next two days, Howie spilled to McNiff: about Winfield's usurious loans and Frohman's gambling and how Winfield spent charity money on the ladies he juggled and how Frohman used the foundation's credit card on personal meals, family gifts, and first-class plane tickets. McNiff took notes. Steinbrenner drew up a memo detailing an attack plan.

Howie's reward, however, would have to wait. Steinbrenner was building a case against Winfield at his own pace. His offensive wouldn't begin until 1989, when Winfield sued Steinbrenner for ducking his financial obligations to the foundation. Steinbrenner countersued, using Howie's info as ammunition. Eighty percent of the foundation's funds, it turned out, were going toward administrative costs, limos and untraceable personal expenses. Even as he sued Steinbrenner for not paying the foundation, Winfield hadn't honored his own obligatory annual $100,000 donations.

So for three years, Howie stewed in his parents' apartment, waiting for Steinbrenner to make his problems disappear. He was convinced there was a contract hit out on him. He called McNiff 10 times a day and referred to him as "my second father." He wrote him angry letters about Steinbrenner: "What Dave and organized crime couldn't do, George did. He killed me. Is he an animal or just a monster?" In some letters, he talked about deteriorating and needing help, and about the apocalypse that might ensue if he didn't get it: "The extraordinary explosion is coming and very, very soon."

When the explosion came in the middle of 1989, it was indeed extraordinary. Howie took to the phones. He dug up numbers for Steinbrenner's hotels, his house, his farm, his mother, his wife, his kids, his brother-in-law, his employees at the Yankees, his housekeeper, his barber. He subjected them all to the treatment. He railed about Steinbrenner's treachery. He told Steinbrenner's lawyer that he was "a slave … a wimp, a flunky and a liar." He threatened to kill himself.

At one point, Howie returned to Tampa in an attempt to force a meeting with Steinbrenner. In the airport, he chatted up a beautiful girl. They whispered of the fun they'd have later. She was 16, Howie said. When she walked off, two cops grabbed Howie and threatened to book him for soliciting a minor. McNiff cleaned it all up, Howie said, but Howie knew Steinbrenner had set him up. He just knew it.

Back in New York, he only cranked up the pressure. He showed up in a raincoat at the Regency Hotel where Steinbrenner was staying and scrawled ominous messages on hotel stationery. In other letters, he talked about meeting Winfield "one-on-one" and about buying a pistol, and he warned Steinbrenner to beef up security. "I want to come out of this wealthy or I want to come out of it dead," he wrote. He threatened to tell the press about Lou Piniella's gambling and about high-level Yankees employees selling extra giveaway items for personal gain.

Above all, Howie besieged McNiff. More than 20 years later, the mere mention of Howie's name was enough to make McNiff's wife gasp and hang up the phone, enough to make their son call me back to plead for mercy for his parents.

Steinbrenner and Winfield settled their dispute in September 1989. Winfield agreed to reimburse his foundation for inappropriate expenses and to make good on the $229,000 he owed in obligatory payments. Howie continued to rage at McNiff about Steinbrenner's ingratitude.

"I caused all this!" Howie shouted. "He didn't even say thank you!"

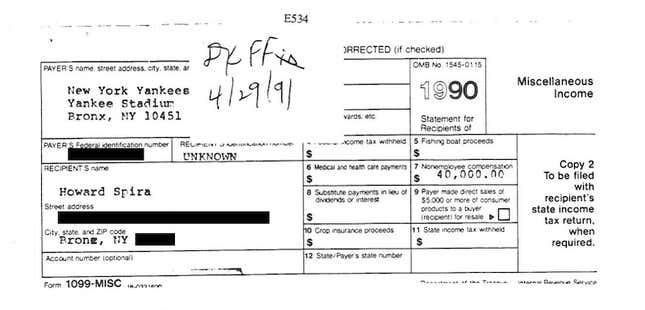

On Jan. 8, 1990, Steinbrenner finally released two checks to Howie that totaled $40,000.

But Howie demanded more. "You left me to die in the Bronx," he wrote. He wanted the rest of the nut: $110,000. Otherwise, he'd reveal his arrangement with Steinbrenner and air out the tapes he'd made of their conversations.

AUDIO: Steinbrenner and Howie get into it

"I'm forced to slit my own throat but before I do I'm gonna make everything that I've gone through public to the whole world," he said.

"That's extortion in the purest form," said Steinbrenner. He was taping their calls now, too.

* * *

My phone rang. I stared at it balefully. It was him. Again. As we neared publication, Howie's anxiety had spiked. I began to understand how Steinbrenner, McNiff and the FBI must have felt. When he couldn't reach me, he called the main Gawker number and harassed anyone who answered. I arrived in the office to find messages from co-workers: "Some very angry man just called for you" and "MY LIFE DEPENDS ON SPEAKING TO LUKE!"

We'd talked about possibly going to see a Yankees playoff game, but had never firmed up a plan. Howie yelled at me that I'd broken my promise.

"You give me attitude?! You want to do this? Let's do this."

"Let me just get my tape recorder," I told him.

"Goodbye."

AUDIO: Howie wants nothing more to do with me

AUDIO: "You're not Shakespeare, and you're not Hemingway"

Howie had sucked me into his book-and-a-movie. I half expected him to show up in the office with Charlie Kaufman. In the film, Howie could be a shrieking puppet, exploding out of the phone handset. He had already told me a lunatic story about meeting a hooker who knew a gay porn actor who did security for Christina Aguilera and had knowledge of a transvestite that a Yankees star kept in an apartment on Central Park South. The gay porn actor also happened to be diddling a Hollywood director. Via this most exotic of connections, Howie claimed to have had a few conversations with the director, who had put him in touch with his agent at Creative Artists Agency. The agent stopped taking Howie's calls within the week.

I wasn't so lucky. Howie wanted me to write his book. He spoke derisively of the last writer he'd been in touch with, a man who favored purple prose. Where that writer had failed, I would succeed, Howie believed. He had no one else to talk to, nothing else to do. His life was stagnant, as it had been since prison. At least when he was behind bars, he'd moved around—Laredo, Texas; Lewisburg, Pa.; Morgantown, W.Va., where Howie managed an undefeated softball team called "Spirabrenner's Yankees."

He'd accomplished so little after prison. He still lived with his parents, who were now in their 80s, still slept in the same single bed, springs sticking out. His father was getting loopy from age. At night, the old man's pacing kept Howie awake.

"There's about 50 years of cobwebs in that house," a shrink once told Howie. It was true. The steel bar that kept the mobsters out trapped everything else inside the musty apartment. Black duct tape held together black lounge chairs and less-durable bindings joined the family.

In his bedroom, Howie kept 29 large plastic bins of legal documents, newspaper clippings, and artifacts from his younger days: his Green Hornet ring, his bar mitzvah watch, a graduation book from junior high school inscribed with notes wishing him luck and success. Near his bed was his caller ID and his TV. He watched General Hospital religiously at 3 p.m., the one hour of the day that the world was safe from his calls.

He still loved sports. On his hip, he wore a Sports Box pager that fed him every scoring play of every game in every major sport. "I've had that machine for over 20 years. When I was jail, I used to call home and ask my mother how my machine was."

Howie hadn't gambled since prison. He kept making mind bets for five or six years after he got out. But if he came into money now, he said he wouldn't be tempted. "I would never gamble one penny."

He'd seemingly acquired a new appreciation for frugality. He survived on $697-a-month Social Security payments and Medicaid. Most of it went toward paying for his myriad health problems: gastroparesis and gastritis, soaring cholesterol, hypogonadism, kidney stones, osteoporosis, adrenal insufficiency, psoriasis, a weakened immune system, terrible arthritis where his spine had fused. Once a week, he gave himself an Enbrel injection in the upper thigh for the arthritis. His leg, he said, was permanently black and blue. He took 20 other prescription medications: Prilosec for acid reflux (20 mg; twice daily), Topamax for migraine headaches (25 mg; seven per day), Celebrex (200 mg) two per day for arthritis. He showed me the whole collection.

If he got a job, he reasoned, it would have to come with top-drawer insurance or pay enough to cover the hit he'd take from losing his Medicaid. "It's such an empty miserable existence," he said. "It's like lying in a clear coffin and watching the dirt being shoveled on you. That's what it's like every day."

Howie talked like that a lot—fatalistic, one-liner bromides: "Every time I see a hearse, I think, 'You lucky son of a bitch. At least you got a ride.'" I heard him try them on other people, often when first meeting them. Howie on pessimism: "Not only is the glass half empty, it's broken. I cut my hand. I bleed. I get an infection. I die." Howie on optimism: "Maybe for once the light at the end of the tunnel won't be attached to the oncoming train." Howie on sightseeing: "If I jumped off the Empire State Building, with my luck, I'd land on someone and end up killing them and not myself. Then I'd end up still alive but facing a murder charge."

He'd figured out that a glitch in a pay phone at the Montefiore Medical Center, where he spent a considerable amount of time, would make "Woodlawn Cemetery"—the property across the street—show up on caller I.D. "I thought you'd enjoy that," he said.

After he told me about squealing on the mob and stealing from Caridi, Howie worried that the killers might come for him again, even three decades later. French assured me that the risk was minuscule. But Howie had his own demise on his mind. One afternoon, he stopped in a Sleepy's store to test out the mattress he'd buy after his book-and-a-movie deal. Immediately afterward, he went into a funeral parlor to investigate other options. "Do you take reservations?" he asked the parlor attendant. They did. How close was Howie to the deceased? "Very close," he said, and got into a casket to try it on for size. Or so he claimed.

"Oh, Howie," his mother said, when she heard tales like these.

* * *

The FBI agents came for Howie on a March afternoon in 1990—four of them, big-shouldered, overcoats, search warrant. One man was from New York, the others from Tampa. "Tampa?" Howie thought, as they bulled into his apartment. When he reached for the phone to call McNiff, one agent smirked: "You're calling Phil for help? This is Phil's operation."

It took a moment for Howie to process the news. But it made sense. McNiff had reached out to his FBI buddies in Tampa to jumpstart an investigation. Howie called McNiff anyway. The taped call was preserved in court transcripts:

"If you saw, if you had any idea what was going through my, in my house right now you wouldn't believe what's going on here!" Howie yelled when he reached McNiff.

"I, I'm sure whatever they're doing is orderly."

"I'm not saying it's not, Phil. Is this how you're gonna play it?"

"No. Howie, what do you mean by play it? Uh, what do you mean by play it?"

"You're a son-of-a-bitch."

McNiff asked Howie if he'd shopped the recordings he'd made of his conversations with Steinbrenner.

"Someone else has 'em now," Howie said. "All I have to do is make one phone call and they're on the front page."

Howie's "someone" was Richard Pienciak, an investigative reporter for the Daily News who now works as the national investigative editor for the Associated Press. Pienciak had heard the Steinbrenner tapes. When Howie called him about the raid, he rushed to the apartment.

Howie had taken a manila envelope with copies of Steinbrenner's checks and other documentary backup and flicked it behind his parents' sofa. After Pienciak showed up, Howie feigned a dizzy spell and stretched out on the sofa. When the agents weren't watching, he hid the manila envelope inside a pillowcase, then staggered to his parents' room. He knocked out a screen on the window and tossed the envelope four stories down to the street, where Pienciak and other Daily News employees were waiting.

Or so Howie said. Pienciak told me nothing of the sort happened. "He's trying to get me in the middle of some conspiratorial act to help him avoid having certain information get in the hands of the FBI," he told me. "I wasn't involved in witnessing or throwing anything out the window. Or picking anything up that was thrown out a window. It had nothing to do with the window. Nothing."

"He's lying," Howie said.

"The challenge with Howie," Pienciak said, "is that there are these threads of truth through this sort of cloudy maze that he lives in."

What is certain is that a few days later, Pienciak published his story, complete with images of the checks Steinbrenner had sent Howie. Pienciak wrote that the two men were "unlikely soulmates sharing an obsession of making life miserable for Winfield."

That was it for Howie. The agents came back later that month to arrest him. Howie made them wait while he took a shower and got dressed. If the mobsters couldn't get through the steel bar, the feds couldn't either. "Fuck them," he said. "I wasn't going to jail dirty." When he let them in, the agents put a knee in his back and cuffed him hard.

In New York, Howie was never deemed a threat. What he'd done wouldn't even merit an investigation, one New York-based agent told me. "You can't spend time on that kind of crap," the agent said. "That guy didn't belong in jail."

But Howie had no chance against Steinbrenner and his connections. No chance with FBI agents testifying against him in U.S. District Court in Manhattan. He'd done himself in with all those letters and tapes. On May 8, 1991, he was convicted. "At 3:53 p.m.," Howie said. Extortion, threats, eight counts in all. He was sentenced to 30 months in prison. Even there, he couldn't escape baseball. His first meal was Yankee pot roast.

"That's how I knew prison wasn't for me," he said.

The only comfort for Howie was that Steinbrenner wouldn't go unpunished. After Pienciak's story broke, baseball commissioner Fay Vincent had barred Steinbrenner from participating in the Yankees' day-to-day operations and personnel matters. Steinbrenner couldn't even visit the clubhouse or the owner's box.

At the time, Steinbrenner was so hated in New York that the man who caused his banning was hailed as the team's savior. Awaiting sentencing, Spira went to a ballgame, and Yankees fans sought him out to thank him. "By George! Spira's Loved," the Daily News headline read. Howie never meant to save anything but his own skin. But he didn't mind taking credit for helping the Yankees.

* * *

Howie often sounded panicked when he called. But this was different. He shrieked that he'd just seen his father hit his mother. He wanted to know if he should call the police. He sounded unhinged, delirious.

"That animal! That German animal!" he screamed.

"Are you sure he hit her?"

"I saw it! He shoved her with his arm. She said that's how they play around. But I saw it!

"Can you separate them?"

"If I call the police, she'll take his side. They'll probably arrest me!"

Someone began mashing buttons on the phone.

"My mother is trying to stop us from talking," Howie said.

He stepped away from the phone, leaving the receiver off the hook. I could hear him shouting in the background.

"This Nazi motherfucker! He hit you! He did it! He needs to go!"

A horrible, keening wail began: his mother howling. Howie screamed over her at Sigmund. He screamed with undiluted rage.

"Dirty Nazi! You belong in a mental institution! You should have died in the oven like your mother! Go die already!"

Sigmund must have responded because Howie's voice took on a cruel, threatening tone.

"What are you going to do, German?"

I thought then that Howie might attack his father. The yelling stopped. I heard a strange buzz on the line and hung up and called back a minute later but couldn't get through. Howie later told me his mother had ripped out the phone cord. I considered calling the police. Instead, I called Tom French. He was out. I called Howie's lawyer, Kojo Bentil, who told me he'd handle the situation.

My phone was silent now. The first thing that occurred to me was that the gloom Howie relayed to me on a daily basis wasn't exaggerated. My next thought unsettled me: I wondered if he'd orchestrated the entire incident for the benefit of my story.

Later that day, Howie called back. Nobody was hurt. His parents had gone for a walk. His lawyers advised him not to call the police. A few weeks earlier, he had expressed concern about what I might write about Sigmund. Now he didn't care.

"He is the most disgusting human being who ever lived," Howie said. "He shits everywhere. This is a man who every time I walk into the bathroom, there's shit on the floors, the walls, the ceiling. How it gets on the ceiling I never know. This is an animal. This is a living animal. He has a look like a Doberman pinscher. That German nasty, animalistic, vicious look. He's insane. A couple weeks ago he came at me with a knife and a vacuum cleaner and said, 'I vill kill you.' He's taken the concentration camp out on me."

Holocaust survivors often bequeath depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress to their children. Some pass along survivor's guilt and a fixation on death. Howie seemed to have gotten it all. Maybe that's why he said what he said next about his father. He'd been working up to it for a while, the most pitiless thing he could muster: "I hate this man more than I'll ever hate George Steinbrenner, Dave Winfield, the mob, the prosecutor. More than anyone."

* * *

Howie may have screwed up his life, but not even God would deny that he was also dealt a bum hand. He hoped to go out with a book-and-a-movie. That's all he had left. It was the only bet he could make. But not many book-and-a-movie packages end with the main character getting a book-and-a-movie. You have to make your own ending first. And Howie didn't know how.

Secretly, he didn't think he'd ever get a deal. Beneath all the dramatic posturing lurked resignation. Beneath that lay regret. He asked me several times if I thought Steinbrenner would have left him alone if he hadn't issued an ultimatum in their final conversation, threatening to go public. I had no answer for him.

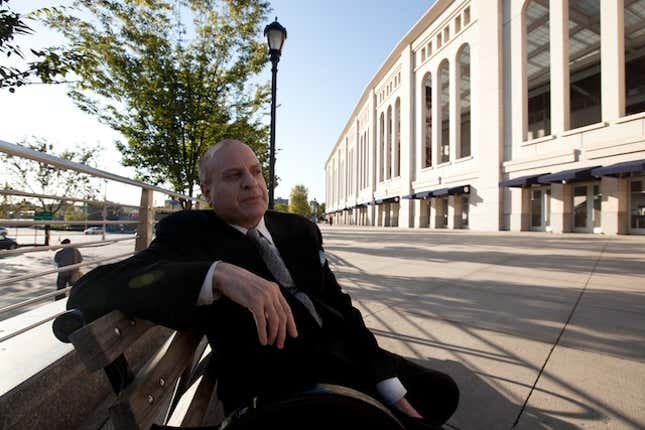

During the playoffs, he would leave his apartment at 5 a.m. and walk to Yankee Stadium—the new Yankee Stadium, with the Steinbrenner monument in the outfield. It took him more than an hour. When he arrived, he sat on a bench facing the stadium, no more than 100 feet away from the gate but an eternity away from what he dreamed of as a young man. He thought about how his dad used to take him to games. He thought about what had become of his life. He sat there until the sun came up.

At least, that's what Howie said he did.

Top artwork by Jim Cooke. Photos of Spira by Noah Fowler. Photo of Caridi by the Associated Press. Spira and ballplayer photo courtesy Howie Spira. Gossage photo via Baseball Wiki.