Heal: Emerging technology making the world healthier

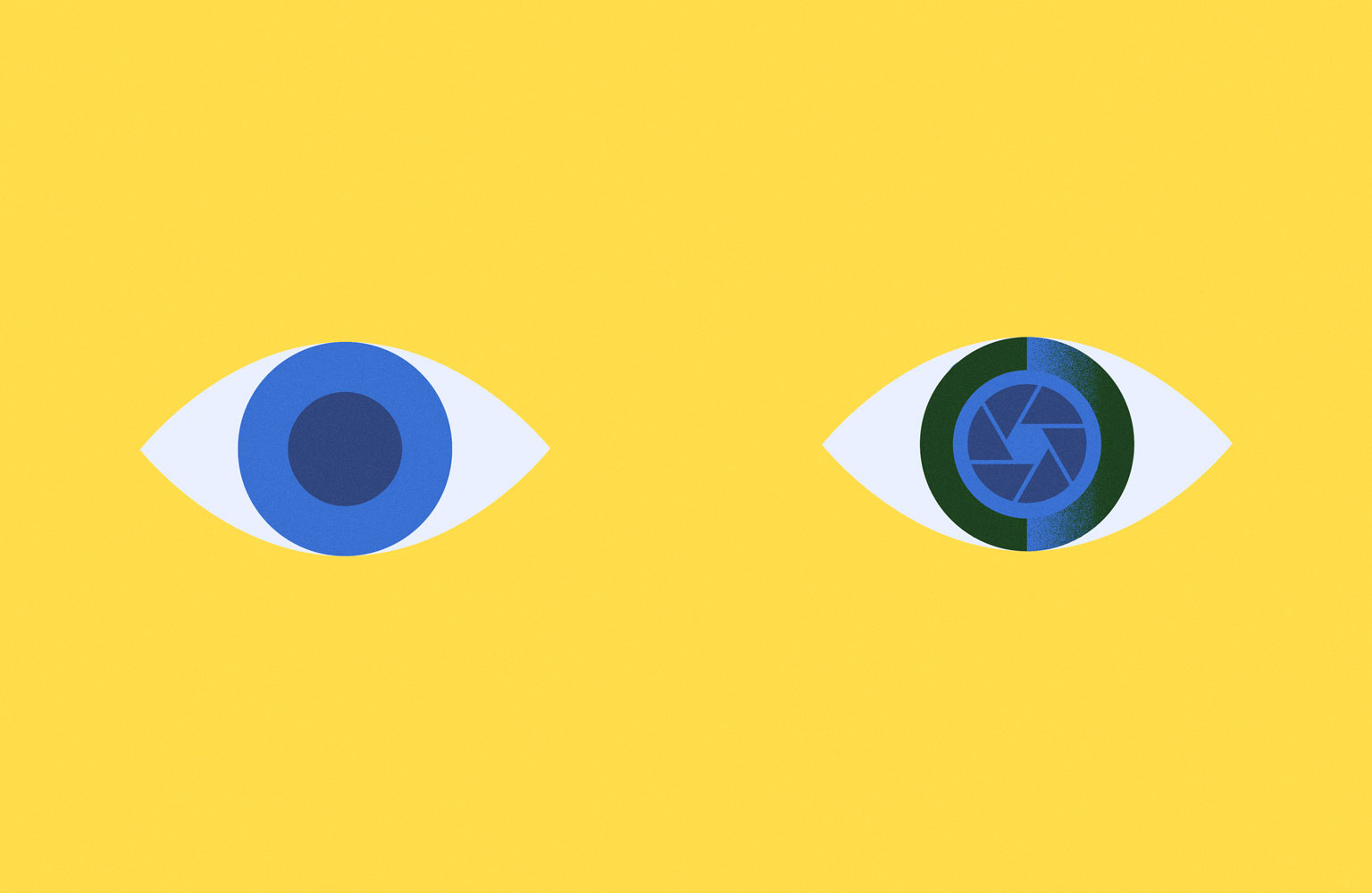

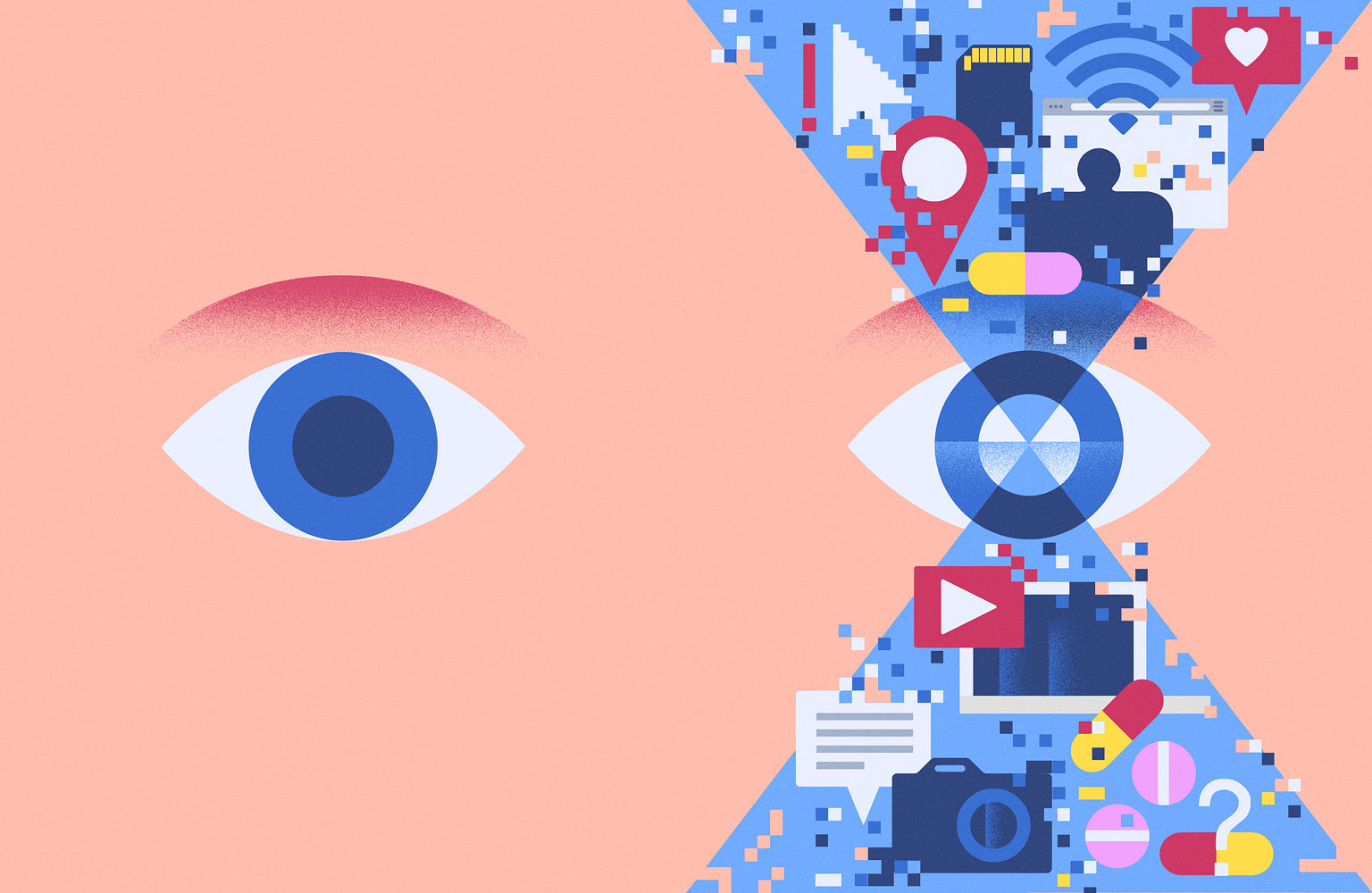

The Contact Lens That Could Turn You Into a Camera

Smart, connected contact lenses are in the works, and they can do everything from record video to keep your entire body in better health.

It’s straight out of a television show: contact lenses that can virtually turn the wearer into a computer. Less invasive than a microchip in the brain and less bulky than an actual computer, smart contact lenses could literally change how we see the world—and how it sees us.

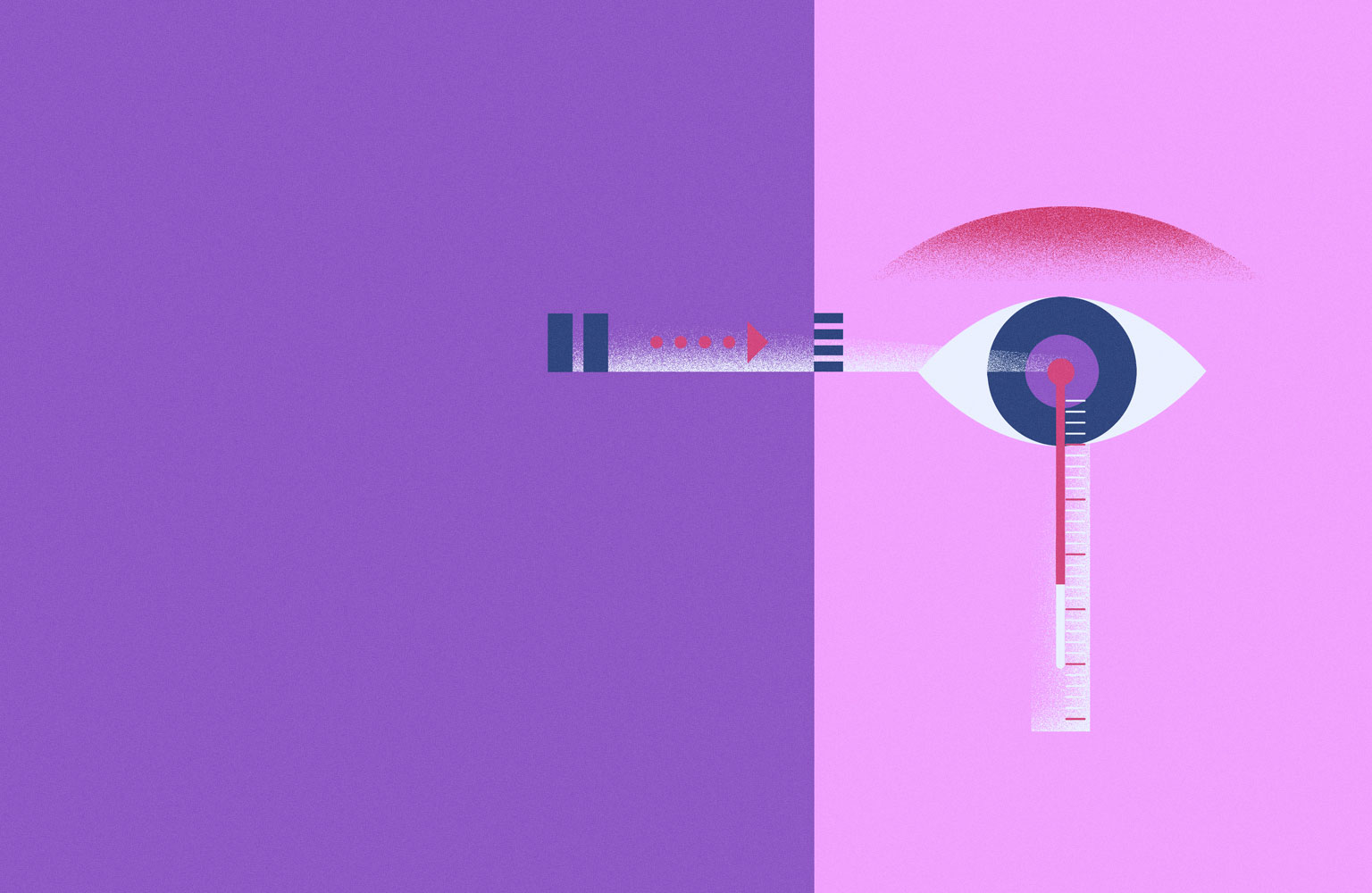

It’s not just an abstraction: Several medical companies are filing patents for lenses that could do everything from release allergy-relief medication to monitor a wearer’s biometric data. Here’s what else the next frontier of wearables could do.

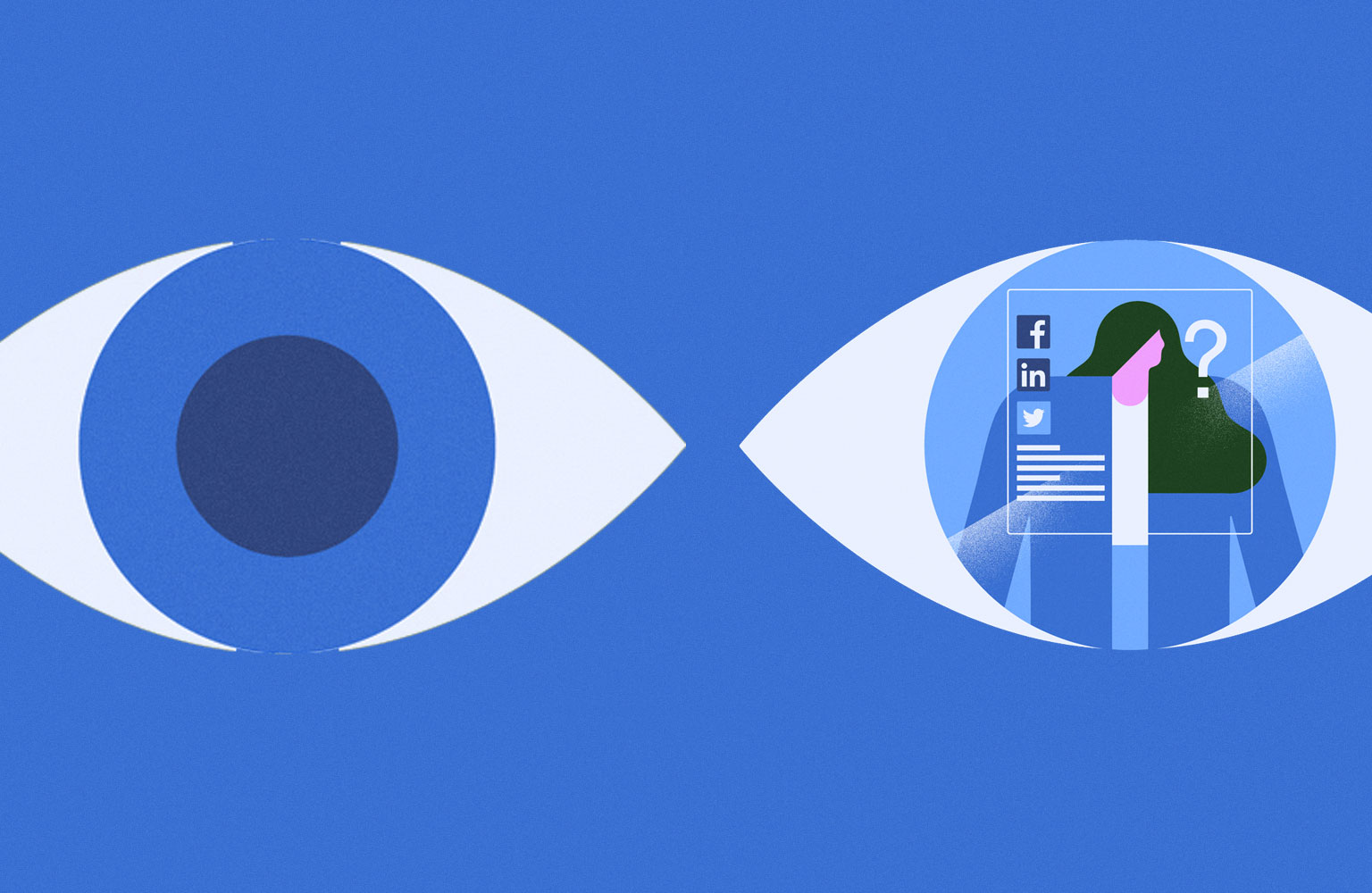

Widespread adoption of lenses that can do what AR and VR headsets do now could help push AR and VR into the mainstream. Resistance to the new technologies typically has to do with the bulkiness of the equipment and the discomfort of heavy headsets. But what would it mean for social interactions and norms if people were able to use the internet invisibly at any time? During a conversation, they could secretly run a search about the person they’re talking to, look something up and view the results, or start watching a video. The technology could distort our perceptions of in-person intimacy and connection on an even more profound level than the smartphone did.

These new lens technologies will require considerations for privacy and data security—as well as for basic safety. You wouldn’t want someone tuning into a television show while they’re driving. But by then, maybe self-driving cars will be doing the job for us.