When My Father Fell Apart, My Stepfather Was There For Me—And Him

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The telephone in my stepfather’s house was mustard yellow and attached to the wall in a narrow passageway beside the kitchen. There was a stool beneath it, where you could sit and prop your feet against the open shelves on the opposite wall, but only if my stepfather wasn’t home. He didn’t like people on the phone for more than a minute. George’s phone conversations, a few per year, lasted less than thirty seconds. He never said hello or goodbye. They usually ended with him saying “Good,” or “Right you are,” clearing his throat, and hanging up. I was a teenager when my mother married him and had been accustomed to hours on the phone every night in our old apartment while my mother worked late.

My stepfather’s house was large—he had seven children and most of them had their own bedrooms—but there were only two phones: the mustard one near the kitchen and the black one in the master bedroom, another area of great tension between me and him. In the old apartment, my mother’s bedroom and bathroom had been our center of gravity, where we talked, watched TV, tried on her clothes, and experimented with her makeup. For the first few years after she left my father, it’s where I often slept. But when she married George and we moved into his house across town, he forbade me to go into their room. If he caught me in there, which he often did, he scolded us both and showed me the door. He sounds like a tyrant and in some ways he behaved like a tyrant, but he had a wry sense of humor and a strong moral compass, and my mother and I loved him dearly. There had been several boyfriends and he was the one I’d wanted her to marry.

The mustard phone on the wall had a long matching spiral cord that could extend away from the kitchen and around the corner and into the clutter closet where you could stand with the mops and brooms or sit on a bucket. Sometimes if you were very quiet as he walked by he wouldn’t open the door and demand that you get off the phone. Sometimes he’d come home from work at the bank, go upstairs in his coat and tie and come back down in one of his faded blue work shirts and grease-stained khakis, and say in a deliberately loud and playful voice to my mother making dinner, "Did you know that our Lily is on the phone in a closet?" Other times he might say very unplayfully outside the door, "C’mon now, that’s enough," and if I were too slow to respond, he’d head back toward the kitchen, pause, clear his throat, and click my connection silent.

My parents had had a bad divorce. They’d been married 21 years and had a long list of resentments. They didn’t speak and I seemed to be the pipeline through which all their anger traveled back and forth. Neither had left our small town in northeastern Massachusetts. They split their friends, my father getting the Republicans and my mother the Democrats. If any of his group communicated with my mother, they were dropped. My father remarried quickly and when my mother started dating my stepfather five years later, it could have been a chance for détente. He and my father were friendly. They had gone to the same high school, my stepfather a few years older, both lauded athletes. Instead, my father put him on his growing list of betrayers.

A year and a half after my mother married George, the fall of my senior year, my father’s second wife left him. He found me before classes started—he worked at my high school—and took me to his office and wept as he told me she was gone. She’d left without warning, just like my mother. He’d never lived alone. He fell apart.

Normally he confined his heavy drinking to the evening hours; now he came to work at my high school drunk. I’m not sure how long this went on. It gets blurry for me. There was a terrible athletic assembly where he slurred his way through a speech about the soccer team he coached. It gets blurry again. November turns into December, I think.

This is the next thing I remember. I’m talking to my father on the mustard phone. I must have called him because he never called me at George’s. It’s early evening and I’m on the stool—I haven’t taken the receiver around to the clutter closet—and my father is telling me he has a knife and he is going to kill his dogs then kill himself. I’m trying to talk him out of it. I don’t know how long this goes on. My stepfather comes around the corner. I brace myself for his scolding and my father’s anger at the sound of George’s voice, the reminder that his old teammate married his wife.

My stepfather has put on his overcoat. "Keep talking," he mouths to me and walks out the back door.

I keep my father on the line. I prop my feet up on a shelf and begin to list all his reasons to live, the things he has to look forward to.

Christmas. My graduation. The Bruins. The Red Sox. The swimming pool next summer and the dogs jumping in. As I speak, I follow George’s car in my head, down our driveway, out the long narrow road to Route 127, past the inn and the field and the gas station, coasting into town, our old apartment on the right, the candy store on the left, Allen’s pharmacy, across the tracks, past the park, up the hill. ‘"My wedding," I say desperately, though I’ve never even had a boyfriend. "You have to walk me down the aisle."

My father’s breathing gets quieter the more things I add to the list. "I don’t know," he whines. "I don’t know."

"The election," I say. He wants Reagan. He can have Reagan. Let him have Reagan and stay alive.

I hear the dogs barking. "Well look who’s here!" my father says in his regular bright voice, as if he’s suddenly on camera. "It’s Shorty. Shorty’s at my door." This was my stepfather’s nickname in school, what all his old friends call him still. I’ve never heard my father use it before. "I gotta go, Lil," he says, like I’ve kept him too long.

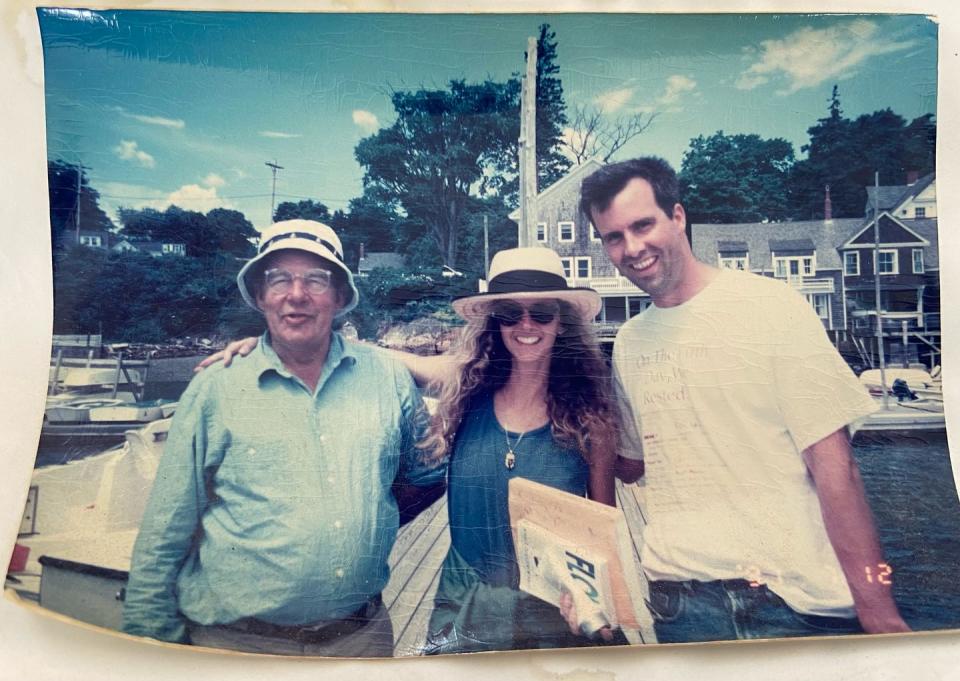

My father remarried again six months later. And he did walk me down the aisle—or down a little path in a garden in Maine. My stepfather wasn’t there that day. He had cancer and was too sick to travel. He and my mother had moved to California by then, and I saw him the following Thanksgiving. His round face had collapsed from the chemo. He stayed in bed the whole weekend. Some months later, when he was out of options and dying, I was too pregnant to travel. My mother held the phone in California to his ear. I could hear him breathing. I told him I loved him. Right you are, I could almost hear him say, just before the click.

Lily King is the prize-winning, New York Times bestselling author of five novels including, most recently, Euphoria and Writers & Lovers. She lives in Maine with her family and dogs.

You Might Also Like