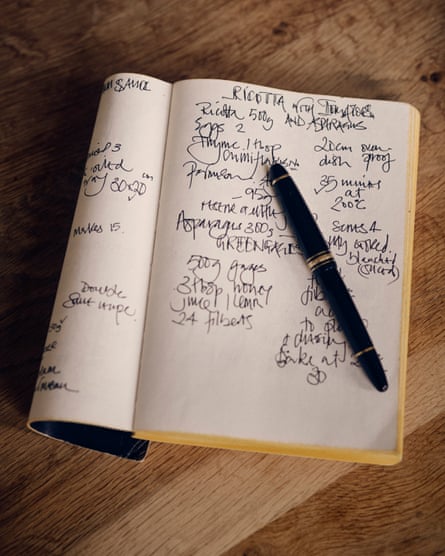

There is a little black book on the kitchen table. Neatly annotated in places, virtually illegible in others, it is the latest in a long line of tissue-thin pages containing the hand-written details of everything I eat. This is not one of the kitchen chronicles where I write down recipe workings and shopping lists, ideas and wishlists, but a daily diary of everything that ends up on my plate. If I have yoghurt, blackcurrant compote and pumpkin seeds at breakfast, it will be in that little book. Likewise, a lunch of green lentils and grilled red peppers, or a dinner of roast cauliflower and a bowl of miso soup. Each bowl of soup, plate of pasta and every mushroom on toast is faithfully logged. I don’t know exactly why or when I started noting down my dinner, but these little books are now filled in out of habit as much as anything else. The notes are often made at night, just before I lock up and go to bed. I suspect my little black books will be buried with me.

I occasionally look back at what I have written, often as I change one journal for the next. One of the points that interests me, and perhaps this is the main reason I have kept the daily ritual going for so long, is that I can follow how my eating has changed, albeit gradually, over the years. There are, of course, unshakable edibles, (I seem to have started and ended each day’s eating with a bowl of yoghurt for as long as I can remember), but I also find marked changes in what I cook and eat. The most notable is the quantity – I definitely eat less than I used to – and there is a conspicuous move towards lighter dishes, particularly in spring and summer.

But here’s another thing. Despite being resolutely omnivorous, it is clear how much of my everyday eating has become plant-based. Although not strictly vegetarian (the bottom line for me will always be that my dinner is delicious, not something that must adhere to a set of strict dietary rules), much of my weekday eating contains neither meat nor fish. I am not sure this was a particularly considered choice. It is simply the way my eating has grown to be over the past few years. I do know, however, that I am not alone in this.

Greenfeast, like Eat before it, is a collection of what I eat when I finish work every day: the casual yet spirited meals with which I sustain myself and whoever else is around. The recipes are, like those in previous collections, more for inspiration than rules to be adhered to slavishly, word for word. But unlike Eat, this collection offers no meat or fish. The idea of collecting these recipes together is for those like-minded eaters who find themselves wanting inspiration for a supper that owes more to plants than animals.

How I eat

I rarely hand someone a plate full of food. More hospitable and more fun, I think, is a table that has a selection of bowls and dishes of food to which people can help themselves. And by that I mean dinner for two or three as much as for a group of family or friends. That way, the table comes to life, food is offered or passed round, a dish is shared, the meal is instantly more joyful.

In summer, there will be a couple of light, easily prepared principal dishes. Alongside those will be some sort of accompaniment. There may be wedges of toasted sourdough, glossy with olive oil and flakes of sea salt. Noodles that I have cooked, often by simply pouring boiling water over them, then tossed in toasted sesame oil and coriander leaves, or an all-singing and dancing Korean chilli paste.

A dish of red pepper soup might sit alongside a plate of fried aubergines and feta. Crisp pea croquettes may well be placed on the table with a tomato and french bean salad. South-east Asian noodles might be eaten with roast spring vegetables and peanut sauce, and a mild dish of creamed and grilled cauliflower could turn up with a spiced tomato couscous. Two dishes, often three, are very much the norm at home. I find the thought of being able to dip into several dishes uplifting in comparison to a single plate piled high. The recipes throughout the book are light. They are meant to be mixed and matched as you wish. A table with several bowls of unfussy food to please and delight, and, ultimately, gently sustain.

A note on the recipes: though all are plant-based, the recipes are not strictly vegetarian. They can, however, be rendered suitable for vegetarian or vegan diets with a bit of informed tweaking.

In a bowl

I am a collector of bowls. Bowls for soup and porridge, bowls for rice and pasta, bowls for pudding. I enjoy choosing which will be most appropriate for my dinner, deep or shallow, with a rim or without, earthenware, lacquer or wood. There is nothing precious about this, I simply feel food tastes better when you eat it from something that flatters the contents.

When I moved to London 40 years ago, I bought a couple of thick, heavy, white Pillivuyt soup bowls. I have them to this day. They were my only tableware for many years, long before I bought plates or shallow dishes. They are used daily, no longer to eat from, but for beating eggs or blending a dressing. There is always at least one sitting in the fridge, a saucer for a hat, keeping a little treasure safe for another day.

The holding of a bowl – more like cradling really – comforts us. But it is important how the bowl feels in the hand. Too rough and it can grate on the nerves, like nails down a blackboard or teeth on a pear drop. Too smooth and your soup feels refined and cold-hearted. What I appreciate most is the humble quality of a bowl and the food you put in it. Even the most exquisitely formed recipe is brought down a peg or two when served in an earthenware dish. The food jumbles unaffectedly in the hollow, the deep sides capture the scent of the food, increasing the enjoyment of every mouthful.

I have a certain reverence for food served in a bowl that I don’t when it is served on a plate. I am not sure why this should be, I only know that it is. I love the way the dressing, sauce or juices sit in the base, to be spooned up as a final treat, which is why so many of the dishes throughout these books are presented the way they are. It is my preferred way to eat.

Greens, coconut curry

Vibrant, verdant.

Serves 2-4

For the curry paste

white peppercorns 1 tsp

coriander seeds 1 tsp

ground turmeric 1 tsp

lemongrass stalks 2

garlic 2 cloves

ginger 3cm lump, peeled

hot green chillies 3 small

groundnut oil 3 tbsp

fresh coriander a handful, with roots

groundnut oil 1 tbsp

vegetable stock 200ml

coconut milk 250ml

fish sauce 1 tbsp

lime juice 2 tbsp

spring vegetables (such asasparagus tips, broad beans,peas) 450g total weight

shredded greens (such as spring cabbage) a couple of handfuls

sugar a pinch

soy sauce

For the paste, put the white peppercorns and coriander seeds in a dry non-stick frying pan and toast lightly for two or three minutes, then tip into the bowl of a food processor and add half a teaspoon of sea salt, the turmeric, lemongrass, peeled garlic cloves, ginger, green chillies, three tablespoons of groundnut oil and a handful of coriander stems and roots. Blitz to a coarse paste. You can keep this paste for a few days in the fridge, its surface covered with groundnut oil to prevent it drying out.

In a deep pan, fry three lightly heaped tablespoons of the curry paste in a tablespoon of oil for 30 seconds till fragrant, stirring as you go.

Stir in the vegetable stock and coconut milk, the fish sauce and lime juice. Add the asparagus tips, broad beans and peas, and continue simmering for five to six minutes, then drop in a couple of handfuls of greens, shredded into thick ribbons. Finish the curry with a pinch of sugar, fish sauce, a little soy sauce and more lime.

Miso, cauliflower, ginger

Gentle soup for a spring day. The warmth of toasted garlic and ginger.

Serves 2

cauliflower 150g

garlic 2 cloves

ginger 30g

groundnut oil 2 tbsp

dark miso paste 2 tbsp

light miso paste 2 tbsp

mirin 2 tbsp

Cut the cauliflower into florets, then slice them thinly. Peel and thinly slice the garlic. Peel the ginger and cut into matchsticks.

Warm the oil in a shallow pan, then fry the garlic and ginger for a couple of minutes until pale and soft. Add the cauliflower, turning it over from time to time, letting it cook for four or five minutes until the slices colour lightly. By the time the cauliflower is cooked, the garlic should be a deep honey-gold. Divide the cauliflower, garlic and ginger between four bowls.

Bring 1 litre of water to the boil, then stir in the miso pastes and mirin. Simmer for two minutes, then ladle into the bowls over the cauliflower.

Shiitake, coconut, soba noodles

Deeply aromatic. Vibrant. Heart‑warming.

Serves 2

For the spice paste

hot red chillies 3 small

garlic 3 cloves

ginger 30g

lemongrass stalks 3

coriander seeds 1 tsp

coriander leaves a handful

ground turmeric 1 tsp

vegetable oil a little

shallots 6 medium

shiitake mushrooms 150g

vegetable stock 500ml

spinach 150g

soba noodles 200g

coconut milk 400ml

coriander leaves a handful

Blend the chillies, peeled garlic and ginger, lemongrass, coriander seeds and leaves, turmeric and a little vegetable oil to a paste in a food processor. Peel and halve the shallots, and halve the shiitake. Warm the spice paste in a wok or frying pan over a moderate heat, then add the shallots and mushrooms. Let everything sizzle for a minute or two, then pour in the stock, bring to the boil, lower the heat and simmer for 15 minutes. Wash the spinach and while the leaves are wet, cook lightly in a pan with a lid. When they have relaxed, remove to a bowl of iced water to stop them cooking any further. Squeeze almost dry and roughly chop.

Put the noodles into a heatproof bowl, pour over boiling water from the kettle and push the noodles down into the water. Leave for five minutes, then drain. Add the coconut milk to the mushrooms, simmer for five minutes, then add the spinach and noodles. Finish with a little fresh coriander.

Chickpea, pea, sprouted seeds

A can of chickpeas from the shelf. Green peas from the freezer. A store cupboard supper for a spring evening.

Serves 4

chickpeas 2 × 400g cans

peas 400g, frozen or fresh (podded weight)

sprouted mung beans 100g

sprouted seeds (such as radish) 80g

olive oil 4 tbsp

ground cumin 2 tsp

ground coriander 2 tsp

For the dressing

tahini 1 tbsp

lemon juice of 1

olive oil 4 tbsp

Bring a pan of water to the boil. Drain and rinse the chickpeas. Cook the peas in boiling water till tender. Drain and refresh in a bowl of iced water. Rinse the mung beans and sprouted seeds in cold water and shake them dry. Make the dressing: beat together the tahini, lemon juice and olive oil.

Warm the olive oil in a frying pan over a moderate heat, add the chickpeas and ground spices, and let them sizzle for a couple of minutes till hot and fragrant. Move the chickpeas around the pan as they brown.

Drain the peas again and put them in a serving bowl with the mung beans and radish sprouts. Fold in the dressing and, lastly, the chickpeas.

One of those everlastingly useful “suppers in minutes”. Use frozen peas or a packet of fresh, podded peas from the supermarket. If you are podding fresh peas for this you will need a generous kilo.

Use whichever sprouted peas you have, including mixtures of lentils and mung beans from health food shops. The point is to introduce as many differing textures as you can.

Rice, pickles, nori

A bowl of steaming rice. The snap of crisp pickles.

Serves 2

carrots 2 large

banana shallot 1 medium

mirin 2 tbsp

rice vinegar 6 tbsp

tamari soy sauce 1 tbsp

sushi rice 190g

dried nori flakes 2 tsp

tsukemono (pickled vegetables)

6 tsp

Scrub the carrots and slice them into rounds no thicker than a pound coin. Put them into a sealable freezer bag. Peel the shallot, slice thinly, then add to the carrots. Pour the mirin, rice vinegar and soy into the bag and seal it tightly, then refrigerate for at least 30 minutes, though it will keep in good condition for several days.

Wash the rice in warm water, drain, then put it in a small, deep pan, cover with 300ml of cold water and soak for 30 minutes. Bring to the boil, lightly salt, then cover the pot tightly with a lid and simmer for 10 minutes. Remove from the heat and leave to rest for another 10 minutes, then lift the lid and run a fork through the grains. It will be fluffy and sticky.

Divide the rice between two deep bowls, then sprinkle with the nori flakes and spoon over some of the crisp pickles, the tsukemono and their juice.

On the grill

I would be lost without my cast-iron griddle, with its well-worn, blackened furrows. You heat it up, slap on a few slices of aubergine, press them down on to the heat with a palette knife or a weight, then lift them off and dress with olive oil, lemon juice and crushed basil leaves. At their side goes a jagged slice of feta or a piece of rosemary-scented goat’s cheese. A slice of toast rubbed with garlic and crushed tomatoes, and you have lunch.

The deep smoky notes, the delicious battle scars and the crisp edges all add to the appeal of cooking on the griddle. If I could only have one method with which to cook my food, it would be this.

But an oven grill is useful, too. The bars of the grill do much for lumps of polenta and slices of halloumi, shavings of courgette and summer squash, and, most recently, halved little gem lettuces and wedges of spring cabbage. The latter need a dressing of some sort, and I usually go for a lemony olive oil one or, better still, lowering the blackened leaves into a bowl of soup.

Polenta, spinach, parmesan

Something substantial for a cool summer’s day.

Serves 4

fine polenta 250g

parsley leaves 35g

spring onions 3

oregano 8g

For the spinach sauce

spinach 300g

double cream 500ml

grated parmesan 5 tbsp

Put 750ml of water on to boil, then, when it is fiercely bubbling, salt it generously and rain in the polenta, stirring as it falls. If you do this from a height, it will lessen the chances of the polenta forming lumps. Lower the heat so the polenta bubbles lazily and keep stirring regularly, getting right into the comers of the pan with your wooden spoon. Take care not to let the polenta scald you – it sends up volcano-like eruptions as it cooks.

Continue cooking and stirring until the polenta is thick enough for the spoon to stand up in the pan. Roughly chop the parsley, spring onions and leaves from the oregano, and stir into the hot polenta. Lightly oil a 24cm × 35cm baking tray and scrape the polenta on to it, smoothing it with the wooden spoon to fill the tin. Leave to set.

Wash the spinach and pile, still wet, into a pan with a lid. Steam for a minute or two, occasionally turning the spinach with kitchen tongs. Remove from the pan and squeeze any remaining water out. Empty, rinse and dry the pan, return to the heat, pour in the cream, stir in the spinach, then add the grated parmesan. Season with a little pepper and set aside.

Using a 6cm cookie cutter or glass as a template, cut discs from the polenta. Heat a griddle pan over a moderate to high flame, place the discs on the hot bars of the griddle and leave until lightly crisp, then carefully turn with a palette knife and cook the other side.

Spoon the spinach sauce on to plates, then put the polenta discs on top of the sauce.

In a pan

A frying pan was one of the first pieces of cookware I ever bought. I now have two: a thin, flat, non-stick pan I use for pancakes and the like, and a heavy, hard-wearing cast-iron version that has a non-stick surface built up from years of active service. The cheaper non-stick pans come and go; the cast-iron pan will, I suspect, pretty much see me out.

All manner of good things can shape up for dinner in a frying or saute pan, from a cake of sweet potato with crushed tomatoes, to bubble and squeak with watercress and dill. Or perhaps a frittata, its thin layer of egg topped with asparagus, finger-thick carrots or shredded spring greens.

Having a shallow pan to cook in gives us the gift of speed. Supper in minutes. It is also possibly the most successful way to use leftovers.

I have made myself many a fine supper from warming a glug of olive oil and a slice of butter in a pan, then adding bits from the fridge – leftover cooked potato, sauteed vegetables or mushrooms, a few cold noodles or a spoonful of cooked rice, then folding in harissa sauce or several shakes of za’atar. A bit of a mixed bag to be honest, with some compilations more successful than others, but something of a blessing when you come home tired and hungry.

Baked ricotta, asparagus

Light, yet not without substance. A homely dish of cheese and eggs.

Serves 2-3

asparagus 300g

ricotta 500g

thyme leaves 1 tbsp

parmesan 95g, grated

eggs 2

a little butter, for the dish

Set the oven at 200C/gas mark 6. Put a pan of water on to boil. Trim the asparagus, discarding any tough stalks, then cut each spear into short lengths. When the water is boiling, salt it lightly, then add the asparagus and cook for two or three minutes. Drain and set aside.

Put the ricotta in a mixing bowl and add the thyme leaves. Add most of the grated parmesan, then most of the drained asparagus, reserving a few of the loveliest spears for the top. Break the eggs into a small bowl, beat them lightly with a fork to mix the yolks and whites, then stir into the ricotta and season with black pepper.

Butter a 20cm soufflé or baking dish, add the ricotta mixture and top with the reserved asparagus spears and parmesan. Bake for 35 minutes till risen, its surface tinged with gold.

More pudding than soufflé, but nevertheless light and airy. A tomato salad would work neatly here, dressed with basil and a dash of red wine vinegar.

Pudding

Not every meal needs to end with something sweet, but it is rarely a bad idea.

Meringue, apricots, blackcurrants

Crisp white wafers of sugar, billowing folds of cream, piquant fruits.

Serves 4

apricots 8

sugar 5 tbsp

blackcurrants 400g

double cream 250ml

meringues 200g

Halve and stone the apricots, and put them in a saucepan with 3 tablespoons of the sugar and 100ml of water. Bring to the boil, then lower the heat and leave to simmer until the fruit is tender enough to crush effortlessly with your thumb and fingers. The softer and silkier the fruit, the better. Remove from the heat and leave to cool.

Pull the blackcurrants from their stalks, then cook in a small pan with the remaining sugar and 100ml of water until the berries start to burst.

Whip the cream in a large mixing bowl till thick enough to sit in soft waves. Crumble the meringues into large pieces, dropping them into the cream. Lift the apricots from their syrup and put into the meringue and cream, then spoon over the blackcurrants and a little of their deep purple juice.

The syrups, devoid of their fruits, can be chilled overnight in the fridge and served with strained yogurt for breakfast.

I like to keep the meringue pieces on the large side so they form a crisp contrast with the whipped cream and soft, warm fruit. Small pieces tend to dissolve into the cream.

Lemon rice, mango, ice‑cream

The contrast of creamy rice, mango puree, cold ice-cream. Warm, yet refreshing.

Serves 4

lemongrass stalks 4 large

creamy milk 500ml

pudding rice 150g

caster sugar (or palm sugar if possible) 1 tbsp

mangoes 2 small, ripe

vanilla ice-cream 4 scoops

lemon 1

Using a heavy rolling pin or pestle, smash the lemongrass stalks, keeping them intact but in large splinters. Put them in a saucepan, then pour in the milk and 500ml of water. Bring to the boil, then remove from the heat, cover tightly with a lid and let the liquid infuse with the lemongrass for half an hour.

Pour the milk through a sieve into a clean saucepan, add the rice and bring to the boil. Lower the heat to a simmer and leave to cook for about 25 minutes, stirring regularly, until the grains are soft and plump. Should they take longer, top up the liquid with a little boiling water. Towards the end of the cooking time, add the sugar.

Peel the mangoes and cut the flesh from the stone, then puree in a blender or food processor. Spoon the rice into dishes, add a pool of mango puree, then a ball of vanilla ice-cream. Finely grate the lemon zest over the rice and ice-cream.

Let the ice-cream soften in the warm rice as you eat.

If your rice is taking longer than 25 minutes, keep the heat at a low to moderate simmer, stir in a little boiling water from the kettle and continue cooking, stirring often, till tender.

One for the Alphonso mango season in June and July.

Sponge fingers, cherry, custard

Much creamy softness here, but with a light, refreshing note at its base that prevents it cloying.

Serves 6

sponge fingers or trifle sponges 100g

orange juice 400ml

apricot jam 5 tbsp

Grand Marnier, Cointreau or sherry 3-4 tbsp

fresh, ripe cherries 400g

ready-made vanilla custard 400g

double cream 250ml

Break the sponge fingers into a deep serving dish about 20cm in diameter. Pour the orange juice into a small saucepan, add the jam and the alcohol, and warm over a moderate heat, removing as soon as the jam has melted. Pour the hot mixture over the sponge, pressing down lightly with a spoon to make sure the pieces are fully soaked. Set aside to cool.

Halve and stone the cherries. Scatter half the cherries over the sponge. Spoon the custard over the cherries, smooth flat, then refrigerate for an hour.

Whip the cream till thick, but not so much that it will stand in peaks. It should sit in soft folds, just managing to keep its shape on the whisk. Spread the cream gently over the custard. Refrigerate for several hours. Finish with the reserved cherries.

The quality of ready-made custard varies enormously. I prefer the premium varieties sold in plastic tubs from the chilled cabinet in the supermarket: the soft, yellow sauces made with eggs, cream and vanilla – you will need to check the ingredients. The budget-priced and low-fat varieties are thin, over-sweet and lack the essential sensuality needed for a trifle.

The exact texture of the cream is crucial. May I suggest you whip it to the point where the cream slouches, rather than sits up straight. An overnight sleep in the fridge, tightly covered with clingfilm, will improve your trifle. Patience will out.

Greenfeast: spring, summer by Nigel Slater (Fourth Estate, £22). To order a copy for £16.99 go to guardianbookshop.com. Free UK p&p on all online orders over £15.