Google Maps' Failed Attempt to Get People to Lose Weight

Not everyone wants to be reminded of calories when trying to get directions.

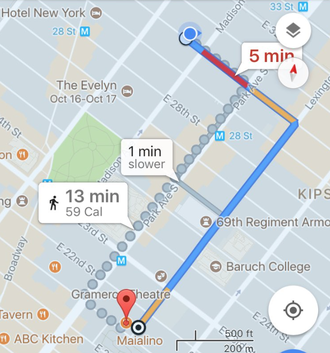

On Monday, the reporter Taylor Lorenz noticed that Google Maps had a new feature: Walking distances were delivered in terms of calories.

Instead of simply telling her that a walk would take 13 minutes, the app also converted that to an amount of energy, 59 calories. Then a click on that calorie count gave a further conversion, from calories to food.

Specifically, mini cupcakes with pink frosting.

This was not well received.

Responses varied narrowly. An ostensible measure to promote health was interpreted as a tech corporation policing women’s bodies.

The writer Rachel Joy Larris noted: “‘Cupcake?’ Let’s talk about all the signifiers that contains about assumptions of gender, culture, and food.”

The writer Dana Cass said, referring to the Harvey Weinstein-induced Me Too movement: “Lol every woman I know has been sexually assaulted and Google Maps is telling me how many calories I’ll burn on my walk to work.”

The app offered no option to convert calorie counts into Budweiser or raw venison.

Within hours, BuzzFeed News reported that Google was simply testing the change, and that it “is removing this feature due to strong user feedback.”

Despite a boom in fitness apps and $1,200 watches that track physical activity, many people do not want to be reminded of calories unless requested. While this sort of nudge may benefit some people, among others the concern is that overwhelming focus on intake and output can drive bulimia or anorexia. In either case, unsolicited calorie counts and cupcake equivalents have an air of body policing and guilt inducement that do not pair well with a culture that assiduously regulates women’s appearances. As writer Casey Johnston offered, “Any woman could have told you this is a supremely bad thing a) to do b) to not be able to turn off.”

In the spirit of no-one-size-fits-all solutions in health, there is more logic in Google considering this as an opt-in feature rather than a default. Tailoring the experience to users in ways safe and driven by evidence would mean more thought than simply forcing pink-cupcake counts on unsuspecting people.

For instance, Google estimated, “The average person burns 90 calories by walking one mile.” Calorie counts vary widely from person to person—walking a mile is a much less energy-intensive endeavor for a professional endurance athlete than a veteran of World War II. Google presumably has the personal data on most of us to make a much more precise calculation—and to suggest more specific incentives than cupcakes or burning calories.

I’ve argued many times that calorie bartering is not usually an effective approach to weight loss or health. Calories offer no insight into the nutritional value of a food, and they are often used by sellers of junk to convince people that they can eat junk if they simply exercise the calories away. But the metabolic effects of 100 calories of Coke on future hunger and energy storage are not the same as a 100 calorie salad, any more than introducing any two 100-pound people would have the same effect on a dinner party.

All of this is part of the consistent theme that obesity prevention is much less straightforward than other public-health challenges. Metabolic syndrome is unique among deadly preventable conditions—it is not the equivalent to if Google Maps were able to track swarms of Zika-infected mosquitoes and suggest alternate routes.

As our behavior is shaped more and more by interactions with phones, our health is shaped by the world that comes to us through apps. The effects can be beneficial or otherwise, but they will not be neutral. This means a serious burden/opportunity on designers to advocate responsibly and strategically for health. That means reckoning with the individual and societal stigma of states of health that affect our outward appearances, and those which are tied to ideas of guilt and moral judgment, and finding ways to make health easy without compromising any individual’s sense of agency in deciding what degree of health they choose to pursue.