Someday, Apple May Make Your New iPhone Out of Pieces of Your Old iPhone

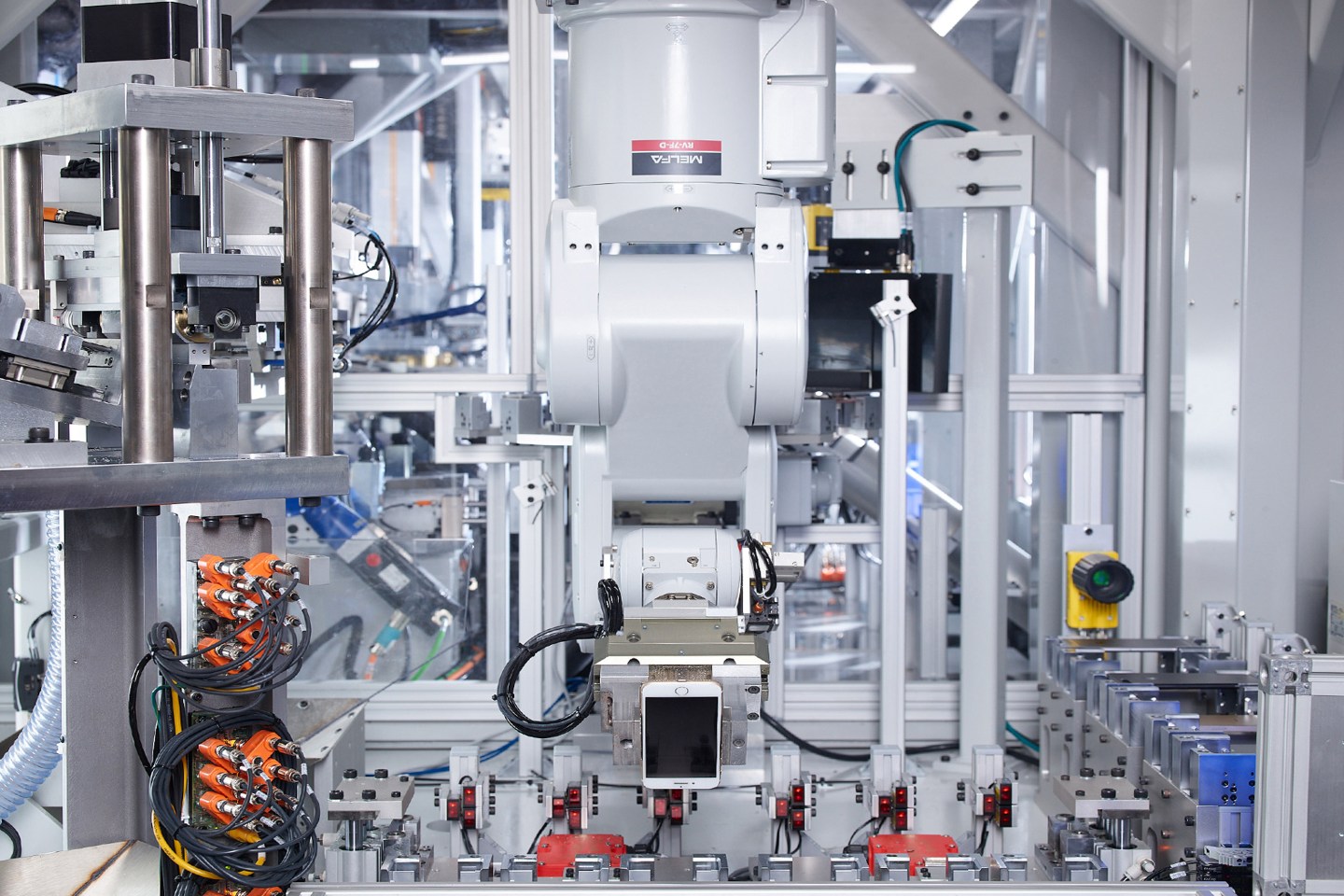

In an unmarked building tucked away in an industrial park in Austin, a location so secret it doesn’t appear on Apple Maps, one of Apple’s latest technologies is hard at work. Inside glass casing, automatic robotic arms move left, right, up, down, and around a conveyor belt with speed and precision. A couple of technicians in blue lab coats, safety goggles, and gloves watch as fog—created by the glassed-in chamber’s extreme cold, which can drop to –112 degrees—billows around one of the arms. Loud mechanical pounding breaks the low hum of running machinery with a uniform thump, thump, thump.

This complicated system, called Daisy, combines automation and a human touch to give Apple its coveted result: scraps of pure plastic, metal, and glass from otherwise-unusable iPhones. “We spend a lot of time in the engineering, making sure our devices stay together,” says Lisa Jackson, Apple’s vice president of environment, policy, and social initiatives. “Daisy was about making sure we had an efficient and effective way to disassemble products.”

Daisy represents not only a breakthrough in electronic recycling efforts—robotically pulling apart an electronic device piece by piece—but also a road map to minimizing environmental impact. Apple prides itself on its green credentials; a high proportion of its supply chain, for example, is powered by renewable energy. Now it’s turning its attention to an equally thorny problem: the fast-growing, often toxic detritus of discarded electronic gear.

Apple in 2017 announced a goal of eventually making all of its products from recycled or renewable material—and eventually, only such material. Apple can’t say when that will happen. (It won’t be soon.) But this building, the Material Recovery Lab, which opened in April, is where the company is doing the research that it hopes will get it there.

Managing e-waste, a category that spans thrown-away equipment from fax machines to smartwatches, is becoming an increasingly complex problem. In 2016 the world generated 44 million metric tons of e-waste, according to the Global E-Waste Monitor. For perspective, that’s the equivalent of about 4,500 Eiffel Towers.

Household e-waste, including consumer electronics, is a smaller share of the pile; last year it accounted for 1.6 million metric tons, or 3.5 billion pounds, according to the Golisano Institute for Sustainability at Rochester Institute of Technology. Total e-waste mass is actually decreasing as companies release sleeker, smaller products, says Callie Babbitt, associate professor at the Golisano Institute. But there’s a new problem on the rise, she explains: “The products we’re using now are relying on an increasingly complex mix of rare-earth materials and precious metals.” And as companies put out new products at an increasingly rapid pace, even automated systems may struggle to keep up.

Apple declines to estimate the size of its own e-waste footprint. The company sold 217.7 million iPhones last year: At an average of about five ounces a phone, that means Apple put about 68 million pounds of materials into households worldwide through phones alone, some of which will eventually become waste if consumers lack a better option.

Daisy represents a “crucial step” toward Apple’s goals, says Jackson, who spent five years leading the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency before joining Apple. The robot, which debuted last year, can disassemble 15 different iPhone models (from the iPhone 5 up) at a rate of 200 devices per hour. The machine at the Austin lab and another in the Netherlands together are processing about 1 million of the 9 million iPhones collected since April through Apple’s trade-in program. (Most of the others are refurbished and resold.)

Apple lists 14 materials used in its products that it hopes to eventually fully recycle. One is plastic, which takes hundreds of years to decompose, poses a threat to wildlife, and can release harmful toxins as it corrodes. Another is lithium, found in rechargeable batteries, the mining of which takes a heavy toll on the environment. With help from Daisy, the company has been able to recover all 14 elements for recycling; it’s already reusing tin and aluminum for new Apple products like the MacBook Air.

Traditional e-waste recycling facilities are less dainty than Daisy. Most rely on bulky machines to shred products, dumping the output into bins of mixed particles. These mixed streams are much harder to recycle, and some elements get lost, stuck, or tossed out in the process. Jackson says Apple wants to improve not only its own processes but also the broader industry’s mulch-it-all approach. Part of its Austin facility is dedicated to broad e-waste recycling R&D, with the hope of developing innovations that will allow all recycling facilities to recover more materials, improving the consumer-tech supply chain.

It’s a long road that will require numerous parts of the industry to get on board if Apple’s goals are to be realized. Even Jackson says she wasn’t initially convinced it was doable. But after talking to engineers and team members, she came to see total recycling as not only possible but also vitally necessary. “If we don’t spend time investing in making sure the hardware is used for a long time and materials are reused,” she says, “it will be a problem we cannot surmount.”

A version of this article appears as part of the Change the World package in the September 2019 issue of Fortune with the headline “Someday, Your New Phone Could Be Made From Your Old Phone.“

More must-read stories from Fortune:

—Fortune Change the World 2019: See which companies made the list

—Q&A: Walmart CEO Doug McMillon on automation, the tragedy in El Paso, and more

—America’s CEOs seek a new purpose for the corporation

—Meet the Change the World Sustainability All Stars

—Change the World 2019: Companies to watch

Subscribe to Fortune’s CEO Daily newsletter for the latest business news and analysis.