Pride and preservation: Lambda Archives safeguards San Diego’s LGBTQ past

The 35-year-old institution has a new outlook, but the same commitment to ensuring San Diego’s LGBTQ stories get told

“(It’s) trying to let them understand, first of all, you have a severely oppressed group of people and it’s done silently, quietly and viciously. And these people have finally come together to respond to that.”

— Robert “Jess” Jessop, January 1990

Joyce Gabiola is used to the confusion when it comes to their job.

In fact, Gabiola, who uses the non-binary pronouns “they” and “them,” laughs and says “it happens so much.” As the head archivist at the Lambda Archives, Gabiola knows what people think when they hear the word “archivist” — that they might envision a job where someone sits in a temperature-controlled room all day, sifting through boxes of ephemera.

For Gabiola, however, it’s much more about what that person doesn’t think about.

“Broadly speaking, archiving and the archiving process entails preserving materials that document lived experiences and historical aspects,” says Gabiola, who was hired in August of 2020. “So it’s preservation while also describing materials. Not a lot of folks like processing, but it’s very interesting because you really get to know the collection donor, the creator. So you have to describe the material so that someone who’s researching later will understand what they’re looking at.”

In the case of the Lambda Archives, which is located just under the Diversionary Theatre in University Heights, this means preserving, documenting and archiving the history of San Diego’s LGBTQ community. Coming up on 35 years in existence, the organization is “one of the best-maintained collections of LGBTQ+ history in the country,” according to its website, but even the concept of “maintained” can be confusing to some people.

“It’s a good question. It’s like claiming ‘world’s best coffee’ or something. I mean, how do you know? What’s the data on that?” Gabiola jokes. “It’s not just the collections, it’s not just the materials. I always say that archives are ultimately about people, not ultimately about materials.”

“A lot of people I’ve found think we’re just putting stuff in boxes and scanning photos, but there’s so much that goes into every little thing you do,” adds Dana Wiegand, who works as the projects manager at Lambda.

To be fair, scanning photos is one aspect of the job, but the archivist also has to take extensive notes while scanning and report any damage that needs to be corrected. When Wiegand first began working at Lambda in 2019, there were a ton of collections that needed to be processed. The extensive undertaking includes taking a collection of materials that hasn’t been organized, and then systematically reorganizing it in a way that Wiegand describes as down to the “smallest detail imaginable.”

It’s hard to imagine someone describing something like that as the “coolest, coolest, coolest thing,” but Wiegand says it will ultimately help to provide an extensive and highly detailed picture of history — a picture that will one day help students, historians and the public at large understand where the LGBTQ community was at in one point in time and, hopefully, where it’s going.

“I know it doesn’t sound cool, sitting down with a box of someone’s old documents and reading through them, but it really is,” Wiegand says. “I’ve always said this is the coolest job I could ever ask for.”

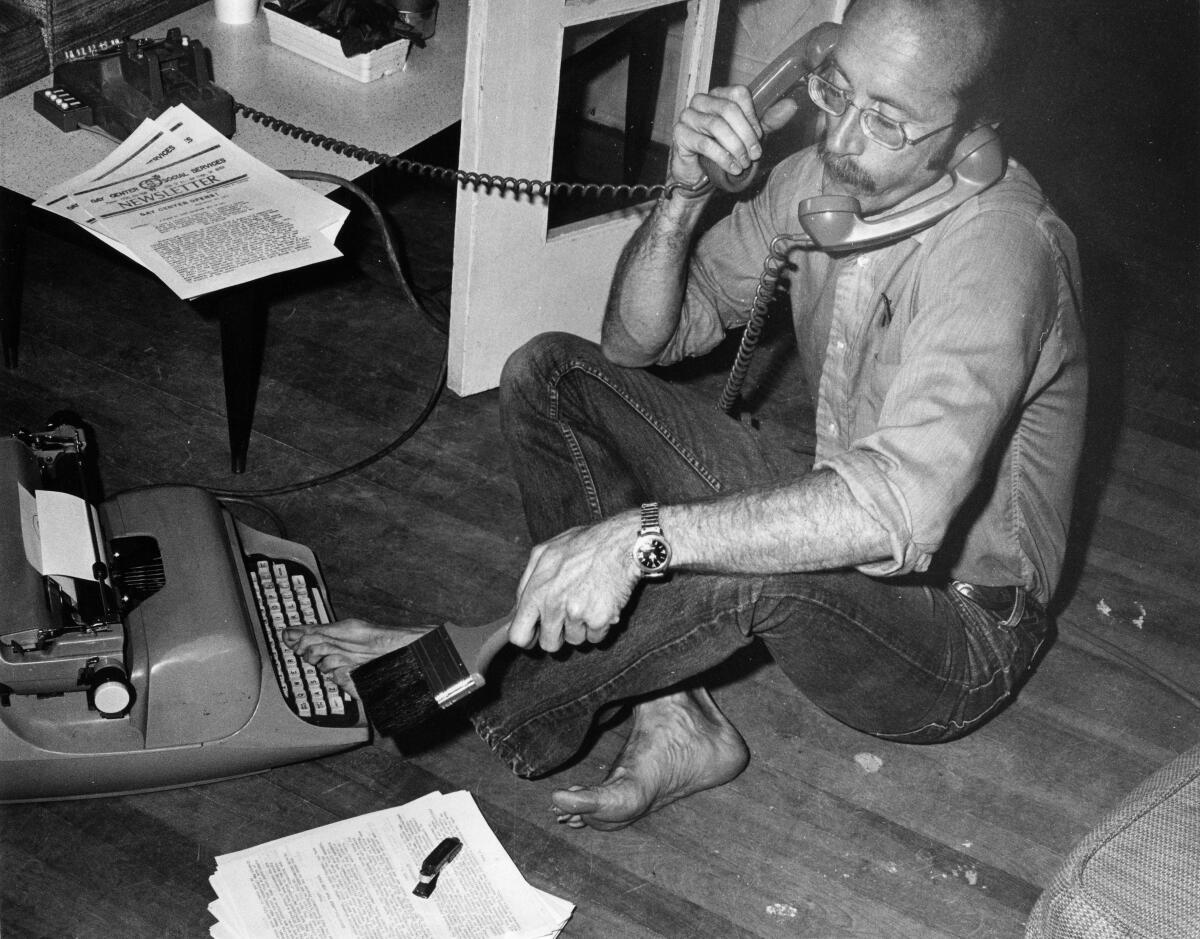

‘We have to do it ourselves’

It was around 1986 or 1987 when Robert “Jess” Jessop began collecting materials for what was then the Lesbian and Gay Archives of San Diego, which would later become the Lambda Archives. Along with Doug Moore, whose documentation would later make up The Doug Moore Pride Papers, the two collections offer a window into an era of shifting thought and action within San Diego’s LGBTQ community. This includes the height of the AIDS/HIV crisis, an increasingly visible Pride movement and a seemingly constant battle against homophobic ballot initiatives and legislation.

“I think Jess started collecting, along with Doug Moore, in the beginnings of the AIDS crisis precisely because he realized that the community’s history was an important aspect that needed to be collected, preserved and eventually used as tools for teaching the story of the community,” says Chuck Kaminski, who serves as the Lambda Archives’ board member emeritus.

Kaminski jokes that his title is “mainly honorific,” but Nicole Verdes, the Lambda Archives board president, sees Kaminski’s role as a community elder as imperative.

“When you’re talking about a historical organization, you certainly must have folks who’ve been around and who can speak to things that have happened in the community or the work they’ve done,” says Verdes.

Kaminski jokes that Pride and the San Diego LGBT Community Center are the more well-known LGBTQ organizations in the city because someone would have to be a “history geek” to appreciate Lambda.

“You have to be someone who appreciates the past and wants to figure out how to take that knowledge of the past and figuring out what it means for the present,” Kaminski says.

One of those history geeks is Frank Nobiletti, who moved to San Diego to go to graduate school at the University of California San Diego in the late ’80s. He was studying what he calls the “formative years of gay liberation” at the time, and recalls perusing Jess Jessop’s collections for the first time.

“They were in Jess’ apartment and he was sleeping on the couch, because the bedroom had papers, books and other archival materials stacked feet high,” Nobiletti says. “So I did some of my first research there.”

What most struck Nobiletti was not so much the vast collection of zines, flyers, posters, pins and other ephemera that made up Jessop’s collection, but more the letters from LGBTQ people who had struggled or who had just found love.

“You could see the loneliness in some of the letters that people sent and then there were letters where people would say how amazing it was to go to (roller)skate night and be able to hold the hand of their partner while they skated around,” says Nobiletti, who is a history professor at San Diego State University. “Just these little things that meant so much to people.”

Nobiletti says he was eventually “roped right in” and was asked to sit on the board of the Lambda Archives in 1990 and remained its principal historian and eventually board president until 2005.

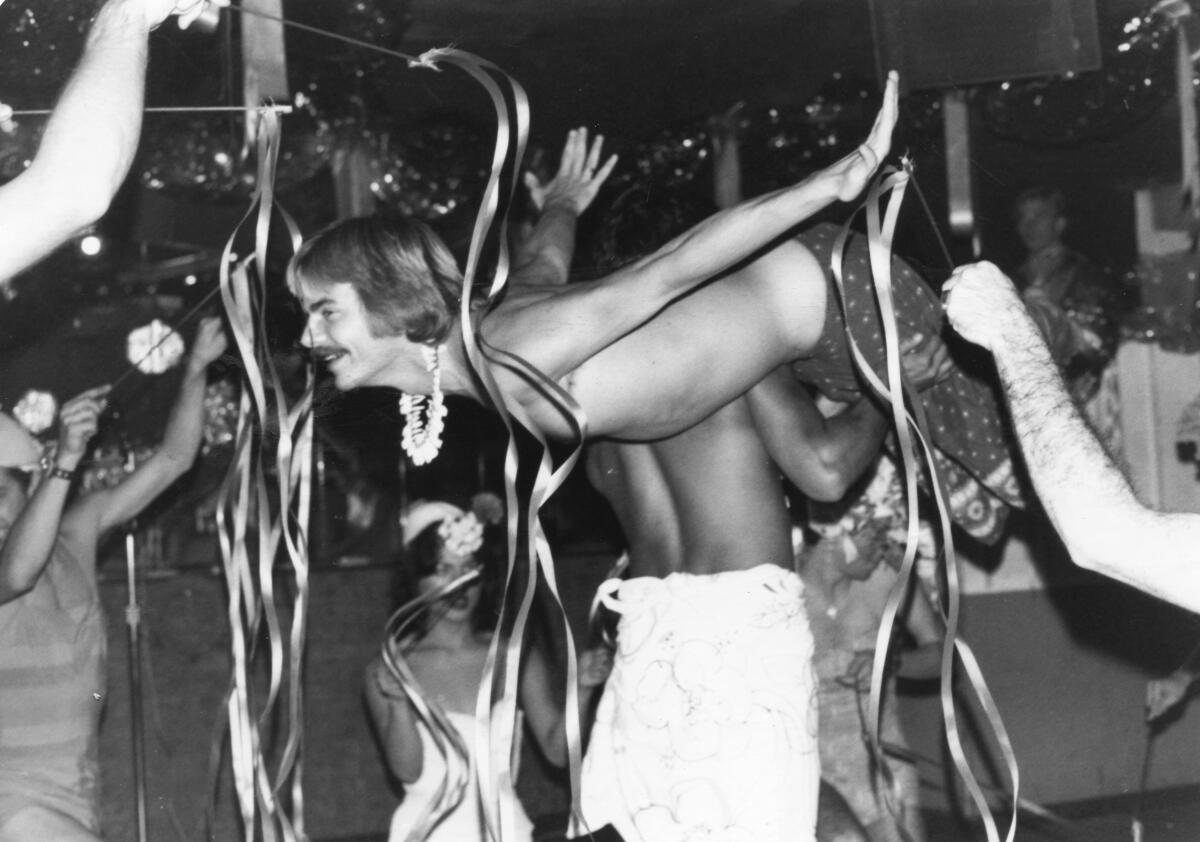

“My key focus was the role of the archives in community building, and that means making things available to historians and other scholars so they could write about it,” Nobiletti says. “But it also meant exhibits and collecting a lot of visual materials.”

“When I got there, it was especially surprising to me that so much had been done for so long by just a purely volunteer organization and just for the passion of the thing,” says Kelly Revak, who worked at the archives from 2007 through 2014, first as a volunteer before eventually being promoted to head archivist and later to the board of directors.

Revak points to the move from an upstairs area at the Diversionary Theatre property to the ground floor as a turning point in the history of Lambda, one that offered the archives more room and space for collections, but also more visibility within the community. Revak also notes a renovation of the space to the “highest archival standards,” from UV-blocking windows to storage rooms that would prevent further deterioration of archived materials.

Another turning point, and one that likely garnered the most public attention, was “A Celebration of San Diego LGBT History,” a 2010 exhibition at City Hall. Revak jokingly recalls that the exhibition “almost killed us,” but “was so important for the community.” Another exhibition, 2018’s “LGBTQ+ San Diego: Stories of Struggles and Triumphs,” only further solidified Lambda’s role and legacy as the keeper of the community’s history.

“That’s the importance of community archives, especially for marginalized communities as a whole, is that we can’t rely on these larger, mostly White, mostly straight, mostly cisgender institutions to bother collecting our history or ever presenting it. So we have to do it ourselves,” says Jen LaBarbera, who worked as Lambda’s chief archivist from 2015 to 2018.

But what distinguishes something as historical as opposed to, say, simply significant? The lines can sometimes be blurry, but LaBarbera points out that this type of discernment is exactly what archivists are trained to pinpoint.

“I wrote my entire thesis in grad school about this,” says LaBarbera. “What do we deem as historic? What is worthy of preservation and important enough to keep and pay attention to?”

She references the Pulse massacre in Orlando, Fla., in 2016 as one such occurrence that the archives wanted to document in real time. Lambda collected materials — items like posters and tributes left at the Pride flag memorial in Hillcrest, for example — to preserve for future generations.

One of LaBarbera’s favorite finds was the discovery of several notebooks from Gary Cheatham, the founder of Auntie Helen’s, a thrift store and non-profit charity founded in 1988 that provided laundry services to those living with HIV and AIDS. The notebooks contained extensive records of not only the charity’s recipients but also detailed descriptions of the people’s sometimes unfortunate circumstances.

“As folks started dying, he would cross their names out and, in the beginning, would write sweet little notes like ‘rest in peace’ or ‘rest in power,’ along with the date they passed,” recalls LaBarbera. “And then as it got further into the AIDS crisis, it just ended up being names crossed out. The notes went away, because, I assume, there were so many people dying.”

Wiegand says she once had to sift through the archives’ reports on hate crimes, which she describes as “devastating.”

“But that’s history,” says Wiegand. “That’s our history and that’s what we’re here to preserve — all these lives that, even through the decades, their lives still have meaning.”

‘Multiple layers of purpose’

The Lambda Archives offices on Park Boulevard have been closed since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, but Joyce Gabiola is excited to reopen. They anticipate this happening sometime in September or October, shortly after the Diversionary Theatre finishes with some renovations that have extended into Lambda’s space.

Gabiola was hired in August, at the height of the pandemic, and they point out this made it difficult to dive headfirst into the new position. But the time during the lockdown restrictions has given Gabiola time to think about the future of Lambda, as well as to craft a vision for the future of the organization.

“One of the reasons we will continue to be described as ‘best-maintained’ is because I’m applying an intentionally anti-racist, anti-oppressive framework to the work that I do in all aspects,” Gabiola says. “This is a framework that is continuing to be developed, especially since society is always changing, so the framework will reflect those changes.”

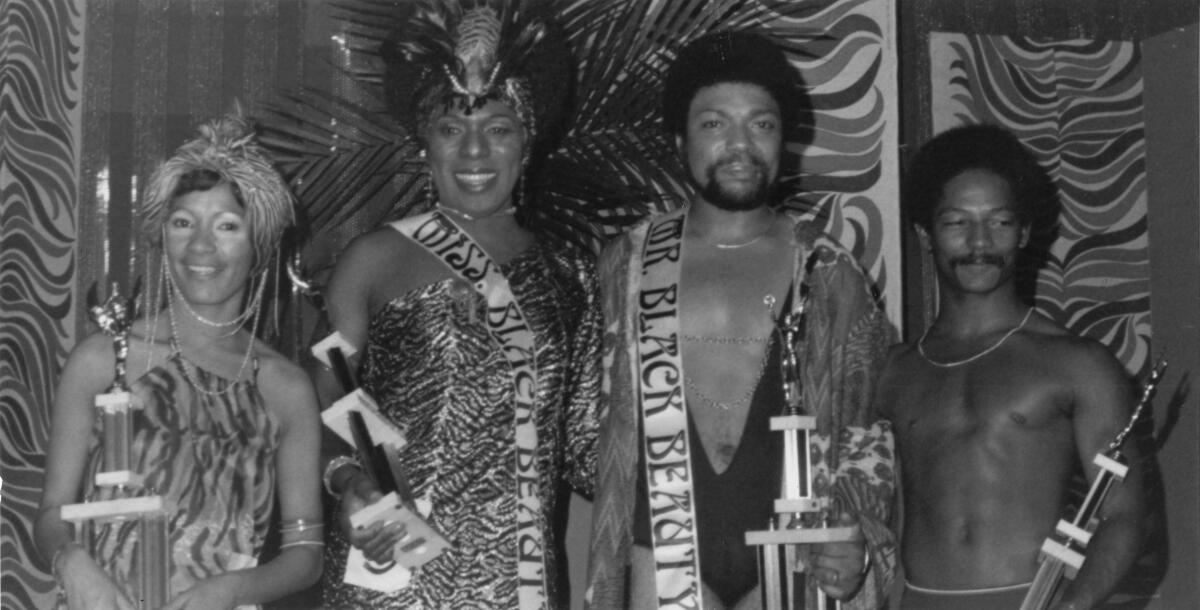

One of the things Gabiola means by this is that the archive has to remain committed to adjusting the language used to describe the archive’s materials in order to address issues such as race, class and equity. It also means that the Lambda Archives will begin to focus more on Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) stories and collections.

“I want there to be, as much as there can be, multiple layers of purpose,” Gabiola says. “So I’m intentionally trying to address that. Let’s prioritize those histories that are often underrepresented or misrepresented or even erased.”

Some of those backlogged collections are already beginning to be archived thanks to a California State Library grant-funded digitization project that began in January of 2020, but was postponed because of the pandemic. Wiegand will be heading up this project and shares Gabiola’s passion to emphasize the archiving of BIPOC material.

“That is a deficit that the archives has right now,” Wiegand says. “We have so many collections from old, White gay men and not as many from Black or Indigenous people of color.”

“As it moves forward, (Lambda) will look at what are the gaps in the collection, whether it’s the Black community, the trans community, the Asian/Pacific Islander community, and asking, ‘are they well represented?’” adds Kaminski. “How was their presence in San Diego seen? What did they do? What organizations did they have? Are those pieces missing in the collection?”

As someone who’s been around since the beginning of what would become the Lambda Archives, Nobiletti sees something of a perfect merging of Lambda’s past and future.

“There wasn’t enough trans representation in our time, and there wasn’t enough people of color, so we really had to make an effort to expand that,” says Nobiletti, who adds that he thinks that Jess Jessop, who passed away from complications related to AIDS in 1990, would be proud of Gabiola’s efforts to further expand on Lambda’s mission of community representation. “One of the things that Jess would always say is that the organization should always be anti-sexist, anti-racist, and that was the bottom line.”

Combs is a freelance writer.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.