Applying America’s Superpowers: How the U.S. Should Respond to China’s Informatization Strategy

Centuries ago, China led the world in technology innovation. It invented papermaking, printing, the compass, and gunpowder. Yet China failed to exploit its innovations — instead, the West did. Over time, the West subjugated China and achieved global dominance.

Today, the tables are turning. China is attempting to overtake the West as a global leader in technology innovation, just as the West did to China centuries ago. Chinese leaders are exploiting converged data, communications, machines, and humans at a global scale. With little awareness or understanding by the United States, China is uniting its government, military, and society at large behind a comprehensive, coordinated strategy to enter what President Xi Jinping sees as a game-changing “new era.” Chinese leaders call this informatization.

Informatization can be understood by anyone who uses a smartphone as the way in which digitally intelligent capabilities are changing every aspect of human life — just as industrialization changed virtually every aspect of human life during the Industrial Revolution. From everyday products in the home to military capabilities, devices have become interconnected via digital networks and are “informing” through ubiquitous sensing and autonomous information processing. This interactivity creates unprecedented opportunities and threats. Governments and individuals and organizations of all sizes are building both artificial intelligence (AI) and weaponized cyber threats on the foundation of informatization.

In an informatized world, hardware (more accurately: virtually all physical things), software, and humans converge to create flexible platforms that combine an astonishing array of shared services to deliver new capabilities. For example, anyone can use their smartphone (where two platforms, the wireless network and the internet, combine) to enable location-dependent search to find, for example, “an all-night pharmacy near me.” Individuals, businesses, and governments use platforms for social media and e-commerce, as well as to manage entire business or government enterprises.

The platforms can also be used to monitor populations, engage covertly in “active measures,” defend critical infrastructure, or defeat an adversary. While a nautical engineer could never hope to build an aircraft carrier by him or herself, today a single skilled hacking unit can remotely threaten an entire aircraft carrier group.

U.S.-based technology titans — like Apple, Google, Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft, Airbnb, and Uber — are all building their success on their distinctive platforms. These interoperable products depend on organizational agreements, operational procedures, and technological standards — or “platform prerequisites.”

For instance, the Transmission Control Protocol/ Internet Protocol (what is now known as the TCP/IP stack), governs all messaging between internet-enabled devices. Beginning with Bob Kahn and Vint Cerf’s work at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency in 1972-1974, and originally known as the Transmission Control Program, the TCP/IP stack grew to eventually specify how all data should be “packetized,” addressed, transmitted, routed, and received in a continually evolving network environment. The Department of Defense declared TCP/IP the standard for all military computer networking in 1982. Major commercial enterprises then led a decade-long, international process that replaced all competing protocols with the single TCP/IP standard.

Most U.S. policymakers aren’t familiar with the prerequisites undergirding global commercial platforms and how the Chinese are using platform interoperability to leapfrog the United States. This article explains how U.S. policymakers can use these under-the-hood agreements and procedures to respond to China’s mobilization.

China accurately asserts that the informatization platforms it is building will be essential to its next-generation projection of national power — AI, quantum technologies, and cyber information operations. This article examines China’s actions both as a threat demanding U.S. response and as a model setting the standard for that U.S. response. Finally, we propose new ways for policymakers to assess and respond to the challenge and opportunity created by China’s informatization strategy.

What Is Informatization?

Informatization captures the digital dynamic that is reshaping our world. Xi Jinping has described informatization, or xinxihua, as the modern equivalent of industrialization, given its impact on every aspect of society. Like the concept of industrialization, “informatization” captures the many pieces of the complex social, political, and economic transformation we are living through today.

Informatization is possible because every modern device is an interactive sensor, many containing intelligent capabilities. These devices range from the tools of everyday life (smartphones, tablets, laptops, desktops, cars, power supplies, machinery, medical devices, and security systems) to the tools of national security (biometric identification devices, unmanned aerial vehicles, and stealth weapons). For instance, certain modern smartphones already contain — in addition to a microphone and cameras — an accelerometer, barometer, fingerprint sensor, gyro sensor, geomagnetic sensor, Hall effect sensor, heart-rate sensor, proximity sensor, RGB light sensor, iris sensor, and pressure sensor — plus several radios and more computing power and storage than most major businesses had until recently.

Informatized devices are designed to operate independently while also working together through platform prerequisites agreed to by a number of disparate stakeholders. TCP/IP, for example — as a globally agreed-on technology standard for nearly all online interactions — allowed the explosive global growth and fast evolution of the internet.

Smartphones, to take another example, also run on standard operating protocols. Beginning with the iPhone in 2007, Apple dictated a centrally controlled and updated operating system, inviting application developers to participate within its ecosystem only under its strict control. Android created a more flexible, federated system where each manufacturer (e.g., Samsung) had its own open-source Android variant and was responsible for updating it. Apple and Android both created a set of conventions that constitute the platform prerequisites for their ecosystems, though they each solved the challenge in different ways.

China’s Model and Its Threat

In an effort to leapfrog the United States, China is developing its own advanced informatization technologies and treating the entire country as a single enterprise. Initially, China took much of its technology and strategic understanding of this new era from the United States.

China constructed its national informatization strategy by combining American insights about the power of military platforms — insights generated as part of the so-called revolution in military affairs — with Silicon Valley’s information architecture. China’s leaders, beginning under President Hu Jintao, recognized that they needed to aggregate what had been separate technologies, disciplines, and organizations to create new capabilities, as the United States did in creating precision strike beginning in the 1980s.

China’s military has explicitly acknowledged its debt to the American strategist Andy Marshall, the influential former head of the Pentagon’s Office of Net Assessment and a pioneer of the concept of the revolution in military affairs. Marshall’s biography has been translated into Chinese and one of its co-authors, former Pentagon official Barry Watts, was recently invited to the People’s Liberation Army’s National Defense University. There, Watts told us, he spoke to an audience of general officers on strategic decision-making in the informatized era.

Timothy Thomas, an analyst at the U.S. Army’s Foreign Military Studies Office, has detailed how the Chinese military rebuilt its doctrine, curriculum, and planning around informatization and incorporated Marshall’s emphasis on the revolution in military affairs. Specifically, Thomas analyzes military documents that detail how China plans to use informatization to prevail in information warfare.

Marshall’s influence is not the only way in which China has co-opted American thinking and innovation in the service of its own informatization strategy. Chinese companies such as Huawei admitted stealing product code from U.S.-based competitors such as Cisco, and China reportedly stole the design for its J-20 fifth-generation fighter jet from the United States. Many analysts have pointed out how China is using U.S. technology innovation as the basis for its meteoric rise in the use of informatization. And analysts like Elsa Kania, Joe McReynolds, and others have examined how China is transforming every element of its military, intelligence, private sector, academia, and government to bolster its unified national informatization strategy.

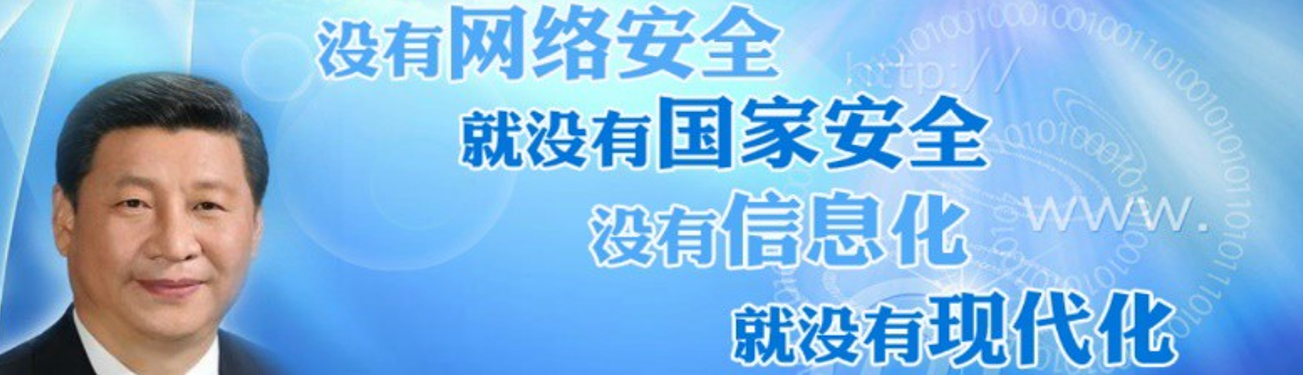

China calls this military-civil fusion, and has publicly announced a number of its unclassified elements. Leadership has used the term to educate both the military and the civilian population about the connection between the digital domain and Chinese national security. As Xi says, “… without cybersecurity there is no national security, and without informatization there is no modernization.”

In the military and intelligence arenas, China is exploiting technologies invented in the United States more strategically than America itself is doing. Multiple Chinese government elements (military, intelligence, and internal security) are collaborating to combine informatized capabilities. For instance, the government is using China’s Xinjiang province as a surveillance laboratory to experiment with “social credit” that will allow the government to monitor every aspect of people’s lives.

Figure 1: Xi Jinping is personally leading China’s informatization strategy. A banner across the top of the official website of the Cyberspace Administration of China shows Xi and the words: “Without cybersecurity, there is no national security; without informatization, there is no modernization.” (Source: China Media Project and Cyberspace Administration of China)

China’s central government has mandated alignment among each of the separate units responsible for platform prerequisites and is coordinating China’s influence on international standards development — for example, on 5G mobility standards. China enforces its alignment requirement in ways that America could not. It seamlessly aligns private with public, military with civilian, publicly-owned with state-owned businesses, and domestic security with international military priorities. In America, these arenas are separated, and for good reason.

China is combining its governmental, military, and “private-sector” efforts covertly as well as overtly. Huge multinational, platform-based businesses are based in China and traded on stock exchanges as if they were private companies. But Chinese Communist Party cells operate more or less openly at the very top of these companies and their associated joint ventures. In line with China’s informatization strategy, the party is directing all of these companies’ under-the-hood platform arrangements with China’s military, intelligence, and internal security apparatus. At a recent event, for example, a former Baidu executive identified the head of the Chinese Communist Party cell as a senior vice president at the company.

The final week of April 2018 made unmistakably clear the full scope, thrust, and vector of China’s informatization strategy. That week, Xi convened the all-powerful group that rules China under him (the six men who, along with Xi, compose the Politburo Standing Committee) for a two-day Work Conference on Cybersecurity and Informatization. According to China Daily, Xi told them that informatization would create “deep integration between the internet, big data, artificial intelligence, and real economy, to make the manufacturing, agriculture, and service sectors more digitalised, smart, and internet-powered.”

Through his “Made in China 2025” initiative, Xi is demanding that China control the “core technology” that will serve as a foundation for all the automation and AI to come. According to a group of New America Foundation analysts, Xi is employing these concepts as “both a tool and a weapon.” They write:

… integrated circuits and operating systems, rather than being merely commercial products churned out by profit-driven firms, actually constitute instruments of national power—whether employed for domestic stability, international security, or economic leadership.

Finally, China backed its leading technology firms (beginning with Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, and iFlyTek, which China now refers to as its AI “national team”) in appropriating cloud technology from the United States. This pattern threatens U.S. interests in ways that extend far beyond commerce.

China is competing with the United States across the entire commercial and military spectrum. Whether in 5G mobility or fifth-generation fighter aircraft, the United States needs to respond strategically.

America’s Predicament: What Works Is Already Known (But Not Being Applied)

If America wishes to keep its competitive advantage, it had best get serious about informatization at the national security enterprise level — that is, in a big-picture sense that incorporates the entire national security apparatus and the technology ecosystem it exploits. The United States has responded to China’s informatization strategy ineffectively and inconsistently. Nothing the U.S. national security enterprise has done so far matches the scale of China’s strategy.

On the positive side, the national security enterprise is beginning to successfully experiment with AI use cases. But, so far, these applications have been limited to specific initiatives and systems. At the same time, many individual offices are considering and adopting data strategies, cloud computing, and shared services in response to system-specific requirements.

But who is assessing informatization at the enterprise level, comparing America’s classified capabilities to those of its adversaries? Who is championing the platform prerequisites needed to meet the integration needs of future U.S. warfighters? Who is coordinating the U.S. strategic response to informatization, a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts?

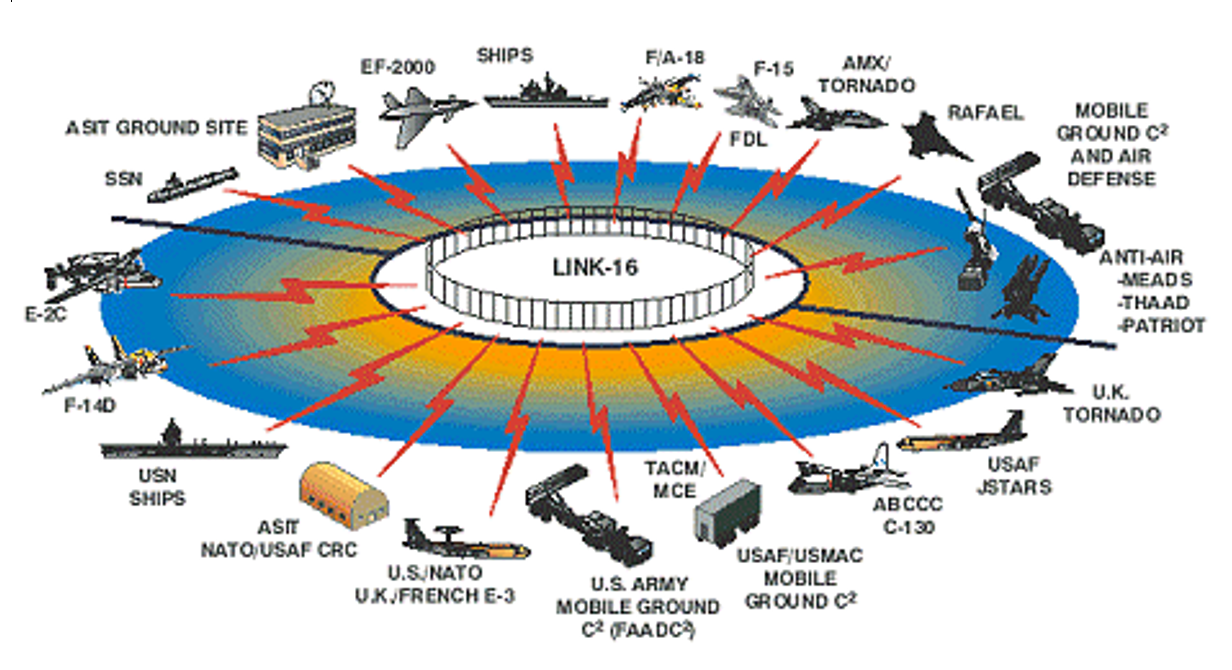

Unfortunately, U.S. national security policymakers are not taking lessons from their country’s leading private-sector technology firms. They have forgotten joint methods that they themselves innovated. Over three decades ago, for example, the United States developed Link 16 as a platform for secure tactical information sharing among the armed services of America and those of its allies. Since then, Link 16 has become a flexible, encrypted, jamming-resistant tool bringing together national intelligence, Air Force, Navy, Army, and cyber assets under the auspices of joint combatant commands. Together with a series of companion platforms, Link 16 makes jointness possible by relaying sensor data and commands in multiple directions.

Figure 2: Link 16, which connects all of the depicted systems, is an example of how platform prerequisites make integration possible. (Source: Naval Postgraduate School Master’s Thesis.Unclassified and approved for public release)

But Link 16 is based on 2G (second generation) cellular systems technology, while today’s cellular systems run on 4G technology and 5G will be here shortly. While RAND assessed in 2005 that the platform reliably links space, air, naval, submarine, and ground signals for joint operations in combat, it needs to be re-envisioned to meet the challenges of the informatized era. Link 16 was able to succeed only because the United States and its allies agreed on its prerequisites at the enterprise level. Because the platform is used by disparate allies, some quite close and other less so, the agreements, standard operating procedures, and standards needed to be solid, secure, and flexible. The same will need to be true for its successor.

Along with lessons of its past joint successes, the U.S. national security enterprise also needs to remember the strengths of America’s industrial base. U.S.-based global informatization leaders (such as Amazon, Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft, and Facebook) are actually leading informatization efforts of their own, each building off the market penetration and technology capabilities of the others, through their interoperable platforms.

An instructive example is the way Amazon Web Services aggregated its shared services to create its broader platform. The cloud capabilities that Amazon Web Services offers grew out of a single 2002 edict by Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos: that the company’s developers would, henceforth, develop only services that could be shared throughout the entire enterprise. According to a former employee, Bezos mandated that from then on, all capability development would be made accessible to the Amazon enterprise as a whole. This meant the Amazon cloud and all its capabilities could be packaged, used by everyone within Amazon’s business ecosystem, and sold to others outside the company. Bezos demanded application programming interfaces for all new functionality and memorably concluded: “Anyone who doesn’t do this will be fired. Thank you; have a nice day!” The U.S. national security enterprise will need to show similar resolve when developing its platforms of the future.

Link 16 and Amazon Web Services are not just technology stories. They are enterprise-wide integration successes. They each created platforms that enabled new ways of conducting business. By using them as models, the national security enterprise will learn to enable each of its elements to innovate with whole new ways of prosecuting the mission.

Conclusion

In the realms of engineering and information architecture, the informatized era makes obsolete much of what the U.S. government has done in the past. Now, the national security enterprise must make decisions that take full advantage of the new possibilities created by informatization, creating the informatized services platforms of the future.

America’s superpowers include, but are surely not limited to, unfettered ingenuity, competitive markets, the rule of law, democracy, and unmatched global alliances. U.S. leaders should harness these strengths in support of a new strategy that will eventually redirect the national security priorities and budget.

No amount of investment in AI, sophisticated weapons, or new proprietary systems can substitute for jointness in the national security enterprise. Only extensive collaboration among senior executives (policymakers from the organizational, operational, and technological mission-critical teams) can deliver the needed integration. Platform integration initiatives are needed not just to transition to AI and quantum technologies, but also to address known vulnerabilities in cyber, the modern order of battle, and fusion warfare. How should building this next generation of platforms differ from past efforts? Platforms that combine intelligence with command-and-control functions, such as Link 16 or the Battlefield Information Collection and Exploitation System, present ideal opportunities to exercise new jointness.

The military depends on the concept of the commander’s intent to direct its most important actions. We propose a commander’s intent to unify a strategic response by the entire national security enterprise rather than subdividing the issues or delegating them down prematurely. Specifically, a “Jointness Tiger Team” should be created to ensure implementation of a uniquely American strategy derived from the enterprise engineering techniques of Silicon Valley. Technology leaders use a similar strategy to limit central control to only those platform prerequisites where it is necessary. This makes room for maximum innovation at the edge.

The Tiger Team would be housed within the Executive Office of the President with full participation from the Defense Department and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. This team would provide a classified-capable home for functions that currently do not exist at the uppermost echelon of the U.S. government:

Senior executive technical review to systematically evaluate the specific joint capabilities (beginning with the enabling platform prerequisites, i.e., the agreements, procedures, and standards) necessary to prevail in informatized conflict. In addition to distinguished advisory board members, the Tiger Team must incorporate younger, informatization-savvy warfighters and developers. The team’s output will serve as the impetus for a corrective action plan.

Operational exercises to aggregate what is known about U.S. capabilities and directly compare those capabilities to those of potential adversaries. The scope of these highly classified joint action exercises will encompass informatized conflict outside traditional military and intelligence boundaries (including, for example, critical infrastructure).

Corrective action to champion the entire package of actions, beginning with the platform prerequisites, needed to transition current processes and programs to meet the challenges of the informatized era.

If America’s strategic response to China’s informatization strategy is effective, U.S.-China relations need not devolve into ever-increasing animosity, and the United States can emerge an even stronger leader of the free world.

Charles Rybeck, Lanny Cornwell, and Philip Sagan, Ph.D., are senior advisers to the U.S. intelligence community and Department of Defense. They are the chief executive officer, chief operating officer, and chief technology officer of Digital Mobilizations, Inc. (DMI).

Image: People’s Daily