Hurricane Anita and the white-winged dove hunters were on a collision course and it didn’t bother Kemper Glick a bit. Whatever the outcome, business was blowing his way. Kemper and his twin brother Kenith had operated the Glick Twins hardware and sporting goods store in Pharr for better than thirty years and they knew a thing or two about nature, human and otherwise. Man the Hunter or Man the Hunted, one thing was constant: someone would end up spending a lot of money. And while the four-day white-winged dove season varied according to the whims of various government agencies and the cupidity of the Rio Grande Valley landowners, hurricanes were a predictable windfall.

Take Beulah, which is what the southern tip of the Texas coast did ten years ago. The hurricane and the 115 tornadoes that it spawned were credited with property loss in excess of $30 million. It was, however, a bonanza for the Glicks. The annual pilgrimage of whitewing hunters had come, bought, killed, and returned home a week before Beulah snarled inland, and by the time Beulah was done with her sport the shelves at the Glick Twins store were virtually bare. “Our carry-over business from Beulah lasted almost a year,” Kemper recalled with great pleasure. It wasn’t even necessary to have a hurricane, just a hurricane scare. This year, in the hours since Anita had veered west and started barreling straight toward Brownsville, packing winds of 150 miles an hour, the Glicks had sold thousands of dollars’ worth of flashlights, batteries, butane stoves, electric lanterns, rainwear, even a few boats. The telephone company had rented fifty steel cots and mattresses for their emergency crew, and merchants and homeowners had purchased more than $5000 worth of tape to reinforce windows.

“We stock, anticipating hurricanes,” Kemper said. “All it takes is a scare for customers to come pouring in. Then, if the hurricane does hit, we have the carry-over business — pumps, shovels, equipment for rebuilding — plus all that government money. That’s an industry in itself.”

“You can’t tell about hurricanes,” Kenith remarked. “Maybe it’ll scare the hunters away, maybe it won’t.”

“That’s true,” Kemper agreed. “Maybe it won’t. Can’t hurt a bit.”

On average, the Glicks could figure on their store doing business in excess of $50,000 during the brief whitewing season. “That doesn’t count the carry-over,” Kemper said. “Things like people buying shotguns on layaway.” Until the government tightened tax loopholes that permitted corporations to entertain clients by handing them a gun and a case of .16-gauge bird shells, the Glicks would sell better than a thousand cases of shells in a four-day season. Now they’d be lucky to sell half that many.

“Since Uncle Sam cracked down on the tax laws, we don’t do the volume in shells we used to,” Kemper explained. “Local people don’t hunt that much anymore, and hunters from outside the Valley usually bring their own shells.” Being victimized by rules and regulations, however treacherous, was part of the sport, and the Glicks, who did all of their hunting with a cash register, had turned it to their advantage. Owners might bring their own shells, Kemper reasoned, but they sure as hell wouldn’t bring their own land. In the old days before there were limits or seasons, hunters lines the highways for miles, daring doves to run the gauntlet. A gunner with an even moderate aim could bag a hundred or more in a single afternoon. But hunters were no longer permitted to shoot from the sides of the roads, and the choice hunting sites, at least in that part of the Valley near McAllen and Pharr, were the rich, fallow grainfields controlled by the Glick twins. The best sites varied from season to season, but each summer the brothers studied the doves’ nesting and feeding habits and then leased several thousand acres of farmland where the birds were the thickest. The going price for hunting on one of the Glicks’ leases was $25 per day per gun.

Kemper studied the dark sky and watched his store window as splotches of rain turned dust into muddy rivulets. A radio behind the cash register broadcast periodic hurricane reports and advice on where to go while your house blew away. There was still about 48 hours until the Saturday noon opening of whitewing season, and if Anita didn’t strike the Texas coast by morning, she probably wouldn’t strike it at all. Kemper looked again at the window, looked through an incredible overhang of ships’ bells, diving helmets, and miles of wire rope, and he could feel the hairs prickling on the back of his neck. He could just make out the rain-streaked silhouettes of a man and a boy pricing one of the aluminum boats out front.

“I’m not selling anything they’re not buying,” Kemper said, reaching for his raincoat.

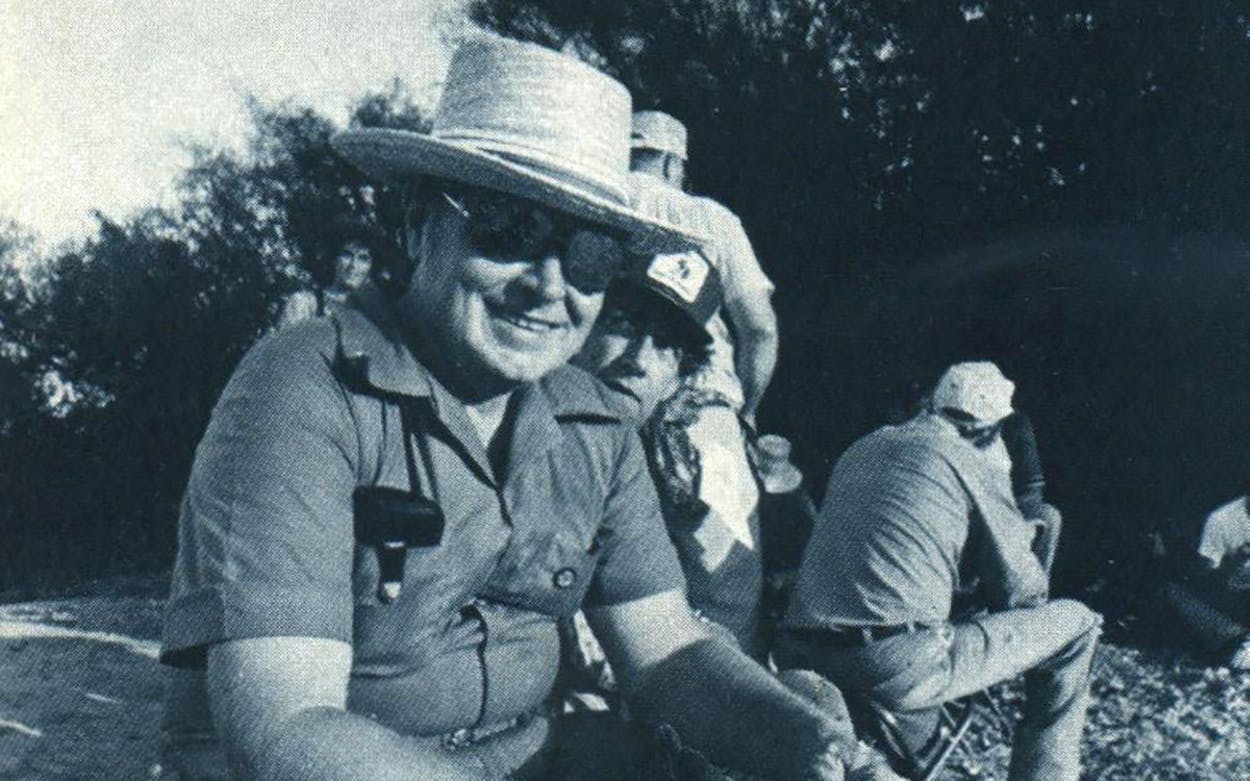

Joe Baraban and Tom Payne used a tank of gas and a case of beer driving from Houston to Brownsville. Joe and Tom are professional photographers, but they are also bird hunters and fishermen. Weeks before the Labor Day weekend opening of whitewing season they bought leases from the Glicks and reserved a motel room in McAllen, and as Baraban’s van plowed through hubcap-deep water on the highway south, they couldn’t help but reflect on their good fortune.

There was an abnormal amount of traffic for a Thursday afternoon, but it was difficult to determine if the exodus of refugees fleeing Anita matched the convoy of vans, campers, and wagons headed into the teeth of the storm. Some of the southbound vehicles contained rescue workers and emergency teams dispatched from Houston and San Antonio, but there were TV mobile units, too, and car pools of reporters who had chased Anita to Corpus Christi and were chasing her now to Brownsville. The great majority of the vehicles heading toward the delta, however, transported men like Joe Baraban and Tom Payne, men who came for the hunt and considered the hurricane a dividend. Radio stations issued moment-to-moment reports on Anita’s location, and the CBs chattered with voices of strangers who cared not where Smokey was positioned but rather how the storm was affecting the migration of whitewings.

“How does it look, good buddies,” the voice of Winchester Willie inquired of all the witnesses. “What about this ol’ hurricane! Gonna hurt the hunting?”

“Negative,” Baraban answered. “Hurricanes have eyes, don’t they? Well, there you are!”

Baraban had wild, wonderful visions of standing on the beach of South Padre Island, filming condominiums blowing away and waiting for the eye, at which time he would pick up his shotgun and bag his limit. Baraban and Payne had hunted and fished together many times. The stories they told were like stories men bring home from war. The time they almost froze to death in a duck blind, or the time a water moccasin large as a linebacker’s arm slithered off an overhanging limb and into their boat. Baraban had a theory about why men hunt. “It’s a death wish,” he said. “Nothing scares me as much as growing old and dying, but every chance I get I’m outdoors trying to kill myself. Maybe that’s what makes life worthwhile — the threat of death.”

But there was a more esoteric question in the ritual of the whitewing hunt: why did thousands of hunters come from as far away as Oregon and Maine to hunt this particular species in the steaming delta of the Rio Grande? The answer was, because that’s where they’re at. South Texas is the northernmost range for whitewings, and the Valley is the only place in the United States where they can be found in large numbers. The mere fact that the whitewing is so exclusive seems to be an irresistible lure to the hunter: one hunter I met had just returned from the Arctic Circle where he had spent five days catching a single fish that was so rare that five days was its entire season. To a birdwatcher armed only with binoculars, the difference between a whitewing and the more common mourning dove is that whitewings are a little larger, a little slower, and a little prettier. Hunters are more impressed with the profusion of the species. A hunter in, say, Dallas can walk all afternoon and see maybe two dozen mourning doves; in the delta, he can look out his motel window and see that many whitewings on a telephone line. “It’s the concentration of birds,” Tom Payne said. “Seeing the sky literally black with doves.” Baraban’s friend David Lipscomb, a young biologist doing graduate work in wildlife science at Texas A&M, explained, “The dove is the most difficult winged animal to shoot. You use an inexpensive, low-velocity shell, and it takes a good amount of preparation for the hunt. The thrill is not in the kill but the anticipation, the preparation. If you could go ‘bang’ and the bird would light up red, that would be fine.”

Although the number of whitewing hunters who invade the Rio Grande Delta increases each year — this year the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department issued 42,000 whitewing stamps — the bird population has remained fairly stable in recent years. It is estimated that something like 460,000 whitewings nest each spring and summer in the Valley: by the first weekend in September, when the hunters arrive, a large number of birds are already flying to Central America for their annual reunion with an estimated seven million relatives. Doves are among nature’s most prolific reproducers, which is fortunate because only a small percentage of the whitewings that fly south in the fall will live to return to the Valley. It is not the hunters alone who decimate the whitewing population, it is nature, human and otherwise. Twentieth-century technology has more than likely killed many more birds than all the shotguns ever manufactured. In the twenties whitewings were so thick along the Rio Grande that one hundred birds per day per hunter was considered a very moderate kill. According to The Bird Life of Texas: “A trip from Laredo to Rio Grande City at any time during the 1930s was like going through a fabulous wildlife preserve.”

In the forties, however, hundreds of thousands of acres of thornbrush, mesquites, and ebony groves, which were the birds’ natural habitat, were cleared for farm- and pasture-land, and the citrus groves of the delta, which had become alternate refuges, were saturated with DDT and other pesticides. Modern methods of harvesting grain enabled farmers to clear their fields before the birds could enjoy a decent meal, and many farmers who planted grain found it profitable to switch to cotton, a crop not to the taste of even the adaptable whitewing. The first recorded decline of the whitewing coincides with the economic boom after World War II. The great norther of 1951 froze 85 per cent of the delta’s citrus trees, eliminating a lot of whitewing nesting habitat. That year only about 100,000 whitewings nested in the delta, down from more than 1,000,000 the previous season. For several years after the norther, there was no whitewing season. Although there are nowhere near the numbers there were thirty or forty years ago, the species has partially recovered from the 1951 disaster. Obviously whitewings do not thrive on bird shot — theoretically, 42,000 licensed hunters could wipe out the entire population in one day; but it’s also obvious that they don’t. As long as the birds have a place to nest and sufficient food, the threat of extinction from hunting is almost nonexistent. The threat from other dangers, however, is very real: many experts doubt that the Texas whitewing population will make it into the twenty-first century.

I don’t know how many whitewings live in northeastern Mexico, but by Friday morning there were a lot less than before. To the great disappointment of dozens of reporters and cameramen, Anita veered suddenly southwest and ripped through an isolated Mexican fishing village 150 miles down the coast from Brownsville. The Texas coast had some high winds and a lot of rain, but it was nothing to write about, and certainly nothing to film. A lot of sandbags, plywood, and window tape went awasting. Those in authority had predicted a power failure — “all it takes in Brownsville is a heavy dew,” a local radio announcer said — but even the power failure was a disappointment, coming as it did only a few hours before daylight. By then most of the reporters had got drunk and passed out, and the hunters who were still awake played poker by candlelight.

Part of the ritual of the whitewing hunt is the trip to Boys Town. There is a zona roja, or red-light district, in every Mexican border town; quality varies according to the affluence of its Texas neighbor, but there is not a Boys Town anywhere quite like the one in Reynosa, near McAllen, during whitewing season. With enough bucks in your jeans, it looks like open season and no limit.

Kemper Glick had pointed out that the whitewing season “keeps us all going. Hotels, restaurants…even whore-town, if you get what I mean.” For the occasion, whores had been brought in from Veracruz and Mexico City, from Monterrey and Nuevo Laredo, from as far away as Acapulco. The prices of everything had doubled and tripled. A $7 motel room in McAllen suddenly discovered itself worth $40. Twenty-five-cent ponies of Mexican beer went for $1, and then $2, and then $2.50. The working girls inflated their product from $18 the first night, when they outnumbered the hunters, to whatever or more Saturday night, when, as one hunter put it, “you can’t find one with a bird dog and a fifty-dollar bill.”

Anita had dumped enough rain in the potholes of the zona roja to make any hunter feel welcome. Clad in bush jackets and boots, the hunters waded through potholes that looked like duck ponds, stalking the savage libido. Many of them, like Baraban and Payne, were just there for the pursuit, letting off a little harmless fantasy. Pouring good money down the rathole is part of living, too, and as the night wore on Baraban and I became convinced that it was our duty to the fellowship of man to buy Tom Payne a girl for his birthday, which it luckily happened to be. Payne wasn’t too sure he wanted the gift. This was Payne’s first trip to Mexico, not to mention his first trip to a border town zona roja. He wasn’t even sure he trusted the water.

For hours we toured bars and the back streets, buying drinks and passing out coins to street urchins, drinking and moving on and talking to hunters. In the Golden Palace, which has no floor show and is therefore the purest of Mexican whorehouses, we encountered Andy, a chemical engineer from Houston. Andy sat with a hooker under each arm and a smile so big it was about to fall off his face. “This is what the season is all about,” Andy said. “I haven’t even bothered to bring my shotgun for the last three years.”

Speck, the personnel manager of a sulphur mine in Oklahoma, advised us to catch the show at a place across the street called Les Paris Follies. Speck hadn’t actually seen the show, but word was out that it featured a young girl and a donkey. “A lot of the guys are taking their wives,” Speck told us. Somewhere between the Golden Palace and Les Paris Follies, Baraban and I lost Tom Payne. We were pushing through the carnival crowds that pervaded the streets and suddenly Payne was gone; disappeared, as though some Big Hand came down and snatched him away in his prime. We decided to go to Les Paris Follies without him.

“We hear you got a girl and a donkey,” Baraban said to the overgroomed hawker who was trying to drag hunters off the street.

“What do you want?” the hawker inquired, tilting his head until the neon glinted off his Jeris hair oil.

“A girl and a donkey.”

“Oh, sure!” he said, pulling us both by the arms. “You got it.” The joint was so crowded with hunters, and in some cases hunters’ wives, that we could hardly see the floor show, which was already in progress. The young girl that Speck had promised appeared to be an import. She must have walked from Yucatan, starting about 1930. Her partner was a pale, skinny boy who pranced around her naked, spread-eagled body, doing tricks with a banana. “A banana!” Baraban wailed. “He distinctly said a donkey!” It was too noisy to hear her lines, but, from the look on the actress’ face, bananas were no worse than donkeys. A young man standing next to me, who had given a waitress a $5 bill for a small bottle of beer and was still waiting for his change, asked seriously, “Do you ever get the feeling we’re the ones being hunted?”

It took a long time to find Payne. He had stumbled into a little out-of-the-way courtyard and fallen in love with a dancer who resembled a sixteen-year-old Lena Horne. Even in the zona roja such talent does not come cheap, but Baraban and I went ahead and bought Payne a birthday present. It goes without saying that we enjoyed it almost as much as he did.

A hard rain was falling as we slogged back to our car. A Landcruiser lit up like an ocean liner navigated the traffic and the water hazards of the main street, joggling the drinks of hunters’ wives as they pressed close to the tinted glass for a better look. “The Gray Line Tour,” Baraban said, and snapped their picture. As the Landcruiser turned down a side street that looked like the set of a Dogpatch porno movie, we read the sticker plastered across the rear bumper. It said: IF YOU TAKE YOUR SON HUNTING TODAY, YOU WON’T HAVE TO HUNT FOR HIM TOMORROW.

After the obligatory stop at the Glick Twins to pick up the lease agreement and stock up on anything else anyone could remember forgetting, Harold Rockaway and his party arrived at an obstacle in the road leading to their assigned hunting ground. The obstacle consisted of a camper and two cars, all mired to the axles in the blue-gray goo churned up by Anita. Rockaway, a Houston psychiatrist who has attracted fame and some notoriety for pioneering private Methadone and mental health clinics and has known more than his share of luck as a championship professional bridge player, enjoyed a professional smile.

“It’s hard to believe, but part of the fun of the hunt is getting stuck,” he said seriously. “My most memorable hunt started in a driving rain with everyone stuck. We were drenching wet, but nobody cared. At the crack of noon we left our cars in the mud, ran for our ammunition and started shooting.”

Dr. Rockaway is a bird hunter, as opposed to a gunner. “I killed one deer and that’s enough,” he said. “Too lifelike for my tastes.” Dr. Rockaway believes that hunting is an atavistic response, a general imprint passed down for thousands of years. He always hunts with his three sons, Mark, 21, David, 19, and Jay, 15. “It’s the way you become a man — hunting,” he said. “For thousands of years hunters survived by killing to eat. It feels almost instinctual to have a gun in your hand. The first time I picked up a gun I really liked the feel. I think of it as a harvest. There is something great about bringing food home. It seems a lot more natural than bringing something from the supermarket.” Dr. Rockaway had observed that very few women enjoy hunting, which supported his theory of genetic imprint. “Women’s lib is going to hate reading this,” he said, “but I don’t think hunting is in women’s genes. Women stay home and take care of things and men hunt.”

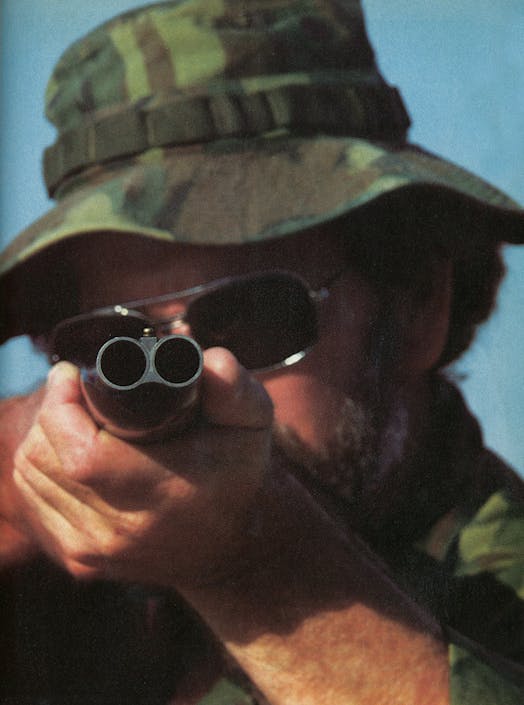

The lease that Dr. Rockaway and his party purchased from the Glicks was 200 acres of plowed pastureland not far from the river. There was no way to determine how many hunters had been assigned to the same 200 acres, but 200 wouldn’t be a bad guess. In all, the Glicks had sold nearly 600 leases, at $25 a day. The Glicks were justifiably proud of their operation. Mud-splattered motorcyclists negotiated slimy trails, directing hunters to their proper places, and a tractor that the brothers had wisely secured from the city pulled vehicles from mudholes, then filled the holes with gravel so other vehicles could pass. The hunters assisted each other with checkoff lists — gun, four or five boxes of shells, folding chairs, ice chest, tote bag, camouflage jacket and cap, bird vest, sunglasses, insect repellent, snakebite kit, first-aid kit, small screwdriver, can of WD-40, heavy-duty scissors for cleaning birds.

The choice hunting sites were those farthest from the road, and Dr. Rockaway’s party trudged happily through a mile or more of ankle-deep mud. In the stifling heat and humidity, each plowed field resembled a rice paddy in the Mekong Delta, surrounded at twenty-five-yard intervals by men with shotguns and camouflage suits, standing patiently or sitting on folding chairs or ice chests. Other hunters positioned themselves in the open fields so they could see the birds coming from all directions. A dove, or for that matter a B-52, would have about the same chance as a balloon at a birthday party.

“Pain and enduring, that’s what it’s all about,” Joe Baraban said. By mid-afternoon Baraban had used up two boxes of shells without reducing the whitewing population a single unit. Baraban attributed this to his hangover, and the fact that he flinched a little more each time he pulled the trigger. His right shoulder was already discolored from the recoil of his gun. Dr. Rockaway and most of his group positioned themselves in a skirmish line, about twenty yards out and facing the trees. Clayton Myers, whose sixteen-year career in the Marine Corps ended in 1971 after he stepped on a land mine, took a post under a solitary oak near the center of the field. It was a strategic location because it placed him far away from the dense thornbrush inhabited by mosquitoes large enough to swallow dove eggs, but the retired gunnery sergeant didn’t pick it for comfort. “I think I’ll get more good shots over here,” Clayton said. “When you get down to it, what I’m trying to do is kill more birds than anyone else. It’s the competition among hunters that keeps bringing me back.”

Jim Johnson, a thoughtful, soft-spoken veterinarian who prefers to think of himself as a wildlife artist, found the most secluded spot of all, an adjoining strip of land where wild mushmelons grew. Johnson had already killed two whitewings and was talking about mounting them for his collection. This was Johnson’s first whitewing hunt, and it would probably be his last. “I enjoy doing things I’ve never done before,” he said. Johnson once stalked a deer for two days, then killed it with a bow and arrow. “It’s the doing that I enjoy, not the killing,” he said. “I could experience the same thrill with a camera, or a sketch pad. I could be very happy just walking through the brush. There is an amazing variety of plant and animal life in the brush.”

It is difficult to reconcile the contradiction of a man who both loves animals and enjoys hunting, but Jim Johnson does, and so do a number of other hunters I met. Jim Johnson recently discovered a chemical that may spare the lives of both sheep and coyotes. The substance is extracted from bitter sneezeweed, a relatively nontoxic plant that leaves a bitter taste in the milk of cows that have grazed it. When Johnson concocted an extract from the weed and sprayed it on the throats of sheep, coyotes quickly lost their appetite for mutton. “I’m still experimenting,” he said, “but the results have been good. I think it could be a very effective way to control predation. Ranchers who go out gunning down coyotes don’t realize that many coyotes don’t attack sheep. Many of the coyotes killed are not the ones causing the trouble.” Men like Johnson are fascinated not with the hunt but with the adventure. Some people are haunted by accidents, and others are terrified they won’t happen.

An hour before sundown: Joe Baraban’s “death wish” hypothesis of why men hunt is not the idle work of a twisted mind but a certified phenomenon that cannot be believed even when you see it. The birds are coming in treetop high, not flocking but swarming like fat minnows in heat, eight or nine or more in crazy patterns, as though some genetic gong has sounded, signaling that it’s every bird for itself. Dozens and maybe hundreds of shotguns explode almost simultaneously and bird shot literally rains down on the roofs of pickups and vans. There are at least twice as many hunters as there were at noon and they are jammed together like hell’s reunion. Dr. Rockaway, who almost blew a friend’s head off on a quail hunt last year, waves his arm and shouts for his sons to spread out, but they are too busy shooting to hear. A fat man in a jump suit squats to recover a dead bird and another hunter twenty feet away wheels and fires a load of bird shot that one second earlier would have cut the fat man off at the shoulders. The fat man stands with his hands up, grinning. “I surrender,” he says. The great, wide delta sky is bleeding dark birds, not just whitewings and mourning doves, but meadowlarks and mockingbirds, anything larger than a mosquito and smaller than a buzzard. Gun barrels are blistering hot and heads and shoulders ache, but the slaughter continues without interruption until the final second when the sun yawns and stretches out below the horizon.

The hunters come to the end of their day like sated warriors, parched, blistered and aching all over, but the volleys are still ringing in their heads and the memories are sealed in places that can never be touched. An excited, red-faced officer in the British Air Force staggers back to meet his American friends at the beer chest. Blood from the zagged rip of a thornbrush mixes with sweat and runs down his face, and he is covered with blue-gray mud from his belt to his boots; but the Englishman has jolly well done it. He has only killed two whitewings, eight less than the limit, and God knows what else he has in his tote bag, but what stands out most in his mind is the memory of seeing his very first Texas rattlesnake. “At first I thought it was a rabbit, but what was I to think, really.” The fat man in the blue jump suit hands him a can of beer and says, “You shoulda shot him.”

The hunters are too tired to talk much over dinner. Post-slaughter depression, I imagine they call it. Dr. Rockaway and his sons celebrate with dinner at the Burger King. Clayton Myers, Jim Johnson, David Lipscomb, and some others ride to Reynosa in Joe Baraban’s van and dine heartily at the best place in town. Everyone agrees that Clayton was the best shot, though David Lipscomb did very well. Their group of nine fired roughly 600 shells and killed 161 birds. They might have killed 19 more, since there is always a tacit agreement in the group that a good hunter can honorably encroach on a bad hunter’s limit. But everyone had enough for today. Joe Baraban’s right shoulder is so sore he has to cock his head to drink. Tom Payne says he feels like somebody busted him in the jaw. David Lipscomb, who has been hunting birds all his life, is almost melancholy as he explains how he won’t shoot a deer and can’t stand the sight of fish. “I like to see birds above me,” he says. “Only sometimes, when I see a dove on the ground bleeding to death, it hurts. It gets harder every year, but somehow the pleasure overcomes the hurt.”

- More About:

- Hunting & Fishing

- Longreads

- Hunting