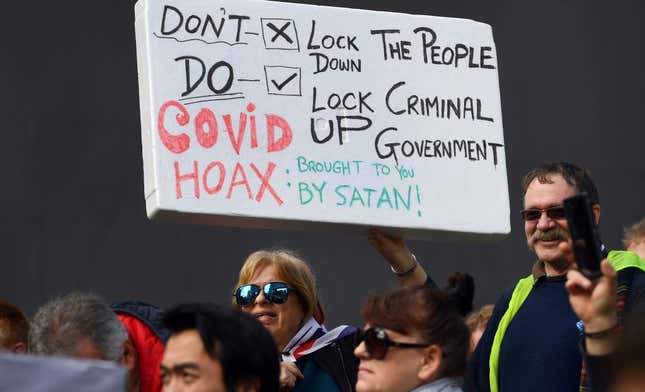

In the past few days, an alarming headline has made the rounds: “Half of Fox News viewers think Bill Gates is using pandemic to microchip them, survey suggests.” This idea is nonsense, of course, but coronavirus conspiracy theories have spread almost like the virus itself across the meticulously calibrated algorithmic networks of sites like YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter, to the point that they’re now part of the national conversation. You’d thus expect that Twitch, another massive and increasingly relevant platform, would be suffering from similar issues. But it isn’t—at least not on the same scale as its competition. It does, however, suffer pervasive conspiracy theory problems of its own.

The most visible example of a coronavirus conspiracy theory springboarding off Twitch and into the wider consciousness happened early this month: Guy “Dr Disrespect” Beahm, one of the most popular streamers on Twitch with nearly 4.5 million followers, spent a chunk of his May 1 stream reading through a widely debunked article advocating for an end to “total isolation” based on irresponsibly obtained data and playing an even more widely debunked video suggesting that 5G cellular technology causes covid-19. For this he faced no consequences of public note, though as of now, the VOD of that particular stream is gone (smaller clips of it remain, however). It’s not clear whether Dr Disrespect or Twitch removed it. In response to Kotaku’s inquiries about Dr Disrespect and how Twitch handles misinformation and disinformation more broadly, a company spokesperson provided a brief statement.

“Consistent with our policies on harmful content and harassment, we take action on content related to covid-19 that encourages or incites self-destructive behavior, attempts or threatens to physically harm others, or any hateful conduct,” the spokesperson said in an email. “While the number of reports we’ve seen on this behavior is very low, we are monitoring closely—as with all emerging behavior on the service.”

This is a markedly lighter response than we’ve seen from behemoths like YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter, who’ve all set about labeling and in some cases removing content related to covid-19, employing teams of fact checkers as part of this process. Facebook has even gone so far as to begin notifying users when they’ve encountered coronavirus misinformation. (These approaches are definitely not without their flaws.) But Twitch is its own platform. While it’s large and growing rapidly in part thanks to a sudden influx of home-bound streamers and viewers, it cannot boast of a billions-strong user base like Facebook and YouTube.

Twitch is also primarily driven by a fundamentally different medium, livestreaming, that serves a different audience. That unto itself poses problems. If a major streamer like Dr Disrespect randomly dons a tinfoil hat, he’ll inflict the majority of damage he’s ever going to inflict in that precise moment, with tens or hundreds of thousands of viewers watching. It’s the nature of a live medium, after all. Labels will not solve the problem. Issuing suspensions or other punishments to the streamer after the fact might send a message, but it won’t halt the spread of misinformation.

At this point, Twitch isn’t even doing that—not consistently, anyway. Back in March, it suspended satirical streamer Kaceytron for making what was clearly a joke (albeit an insensitive one) about spreading the virus to “old and poor people,” but again, it did not suspend Dr Disrespect after he spread actually harmful conspiracy theories with a straight face. And it goes deeper. Until sometime in the past couple weeks, it was possible to find VODs of “Plandemic,” a viral video banned on Facebook, YouTube, and Vimeo that claimed wearing masks causes coronavirus (among many other easily debunked claims), simply by typing “Plandemic” into Twitch’s search bar.

Even now, it is still easy to find Twitch VODs of another video that’s been banned on YouTube, an infamous interview with conspiracy theorist David Icke in which the noted believer in an ancient reptilian race posits a bunch of blatantly false ideas about coronavirus, 5G, and Bill Gates. He’s been a primary driver behind rhetoric that’s led conspiracy theorists to burn down 5G towers in the UK and harass technicians. Twitch also hosts live channels that frequently dabble in conspiratorial information. They’re not hard to find, either. One such channel, a pillar of the notorious QAnon conspiracy community that streams across multiple platforms and has made countless audacious claims about coronavirus, is regularly near the top of Twitch’s politics section.

One thing these VODs and channels have in common, however, is that they don’t draw that many viewers. Even the aforementioned QAnon channel is a big fish in the small pond of Twitch’s politics section, drawing between 30 and 40 concurrent viewers at any given moment and occasionally spiking up to around 100. Why hasn’t Twitch’s community fallen hard for coronavirus conspiracy bait like so many others? It’s hard to definitively say.

In part, though, it goes back to Twitch’s unique history. Despite a now years-long process of diversifying beyond gaming’s stifling confines, Twitch remains defined by that topic. This has led to an ecosystem structured more around gaming highlights and big personalities than intertwined webs of related content across which conspiratorial videos can quietly creep. As a result of gaming-inspired features like raiding, which allows streamers to send their viewers into another channel’s chat, and hosting, where one streamer plays another’s channel in place of their own, Twitch users discover new streamers through other, generally like-minded streamers.

“A lot of the tools that were initially established for gamers to interact with each other—such as raiding each other, hosting each other, and things of that nature—also play very deeply into the social aspect of Twitch as an ecosystem,” Lance from The Serfs, a leftist Twitch channel that has sought to undermine misinformation surrounding covid-19, told Kotaku over a Discord voice call. “So if you raid into another streamer, you’re also kind of endorsing their beliefs. Your audiences are being shared with each other. You’re kind of entrusting your community to another streamer to then talk about issues.”

Will Partin, a researcher at Data & Society specializing in misinformation and disinformation (and an occasional Kotaku contributor), took an even wider view of Twitch as a platform, pointing to a lack of algorithmic connectivity as a reason why individual islands of covid-19 conspiracy content haven’t yet cohered into a more systemic problem.

“If you’re someone who’s interested in spreading problematic information, a lot of times you’re relying on the way that these content management systems elevate particular kinds of content,” Partin told Kotaku in a Discord voice call. “[Twitch] is not like YouTube where the site is constantly feeding you, ‘Here’s another video, here’s another video,’ which creates a pattern that can be exploited much more than how people engage with Twitch, which is often watching a very long stream for a long time—rather than being recommended something [else] immediately.”

I found this assessment to be accurate even when it came to Twitch’s ostensibly somewhat algorithmically driven recommendation system. After days of digging up and watching streams and VODs that touched on coronavirus and other semi-related conspiracies (QAnon, flat earth, etc), the system mostly told me to... watch those exact channels, again. Otherwise, I got a lot of big-name streamers seemingly unrelated to my recent viewing patterns and a couple channels whose broader political aims seemed questionable, but that did not, as far as I could tell, promote conspiracy theories. Twitch’s recommendations are simpler than those of other platforms, in other words.

The company also manually picks channels for its front-page carousel and generally has a firmer hand in deciding what rises to the top than YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter. Lastly, Twitch is a smaller platform in general, making it less attractive to conspiracy mongers who want to sow their rotten seeds in as many fields as possible. Taken together, these factors have so far largely shielded Twitch from more coordinated misinformation efforts like what Partin calls YouTube’s “alternative influence network” of creators who passively and actively amplify each others’ conspiracy theories.

That does not, however, mean that Twitch has successfully quarantined itself from the growing mass of people who’d have you believe that we’re quarantining over a hoax. Twitch is a unique platform with a unique community, but it’s by no means separate from the wider culture that provided its molecules. Streamers have, as a result, engaged with coronavirus misinformation and disinformation in their own ways, all while trying to discern how to responsibly play host to bad-faith ideas designed to spread upon contact—ideas for which they, as tastemakers and trendsetters whose influence brands are lining up to exploit, are the perfect conduit.

This has resulted in a broad spectrum of approaches from influential streamers. On a whirlwind mid-May installment of controversial streamer Tyler “Trainwrecks” Niknam’s popular Scuffed Podcast—on which a large number of streamers regularly gather to discuss various streaming-related topics—viewers got to see nearly every conceivable point on that spectrum represented. A few of the streamers present, including Niknam himself, argued against the idea that streamers who primarily seek to entertain have a responsibility to challenge conspiracy theories or avoid engaging with them.

“I think I should be able to watch a video on 9/11 being an inside job and say nothing at all and end my stream,” said Niknam after another streamer asked if he believed he should be able to air an anti-vax video in full. Others on the podcast, including N3rdfusion CEO Devin Nash and Twitch’s resident political debater Steven “Destiny” Bonnell (who holds some deeply problematic but non-conspiratorial beliefs of his own), argued more or less the opposite—that influencers have, well, influence, and especially when it comes to matters of public health, they probably shouldn’t be throwing their weight behind demonstrably harmful ideas. Still, Niknam pushed back, questioning what it would mean if Twitch or some other body began “dictating what someone can watch and what someone can’t and what they have to say or challenge when they watch it.”

This, in fairness, is a valid concern; Twitch has a long and well-documented history of inconsistent rule enforcement, questionable decisions, and very little meaningful transparency. If the company were to start laying down the law about what constitutes good and bad information, its current methods of rule enforcement would likely come up woefully short and could set damaging precedents. In the stream’s chat, many viewers argued in favor of free speech absolutism—that no “censorship” of any sort should be on the table—while others unintentionally demonstrated why going that far in the other direction probably isn’t the solution either by straight-up posting 5G conspiracy theories, apparently unironically.

This all culminated in a moment when the hypothetical situation the assembled streamers had all just been discussing actually happened. Toward the end of the stream one guest, fighting game veteran Ryan “Gootecks” Gutierrez, decided to explain, at length, why a growing number of people believe that Bill Gates is involved in a covert population-control scheme involving vaccines. During this process, he said he was only “relaying the information,” not necessarily endorsing it, but then, after Niknam reacted to his spiel by saying that everybody should vaccinate their kids and themselves, Gutierrez said, “I think everybody should be free to do what they want with their body.”

In chat, some pushed back and questioned the wisdom of platforming Gutierrez’s speech. Others said they’d heard the same things and believed them to be true. Niknam, to his credit, tried to counter the anti-vaccine sentiment, but this segment also demonstrated the perils of platforming conspiracy theories in a live environment. Gutierrez went on for multiple minutes and touched on a dizzying array of topics. Niknam would’ve needed research on hand to shut down each specific point. While other streamers on the podcast pushed back where they could, their efforts were by no means comprehensive. Misinformation thrives when it’s allowed to seep into small holes in people’s knowledge, potentially sparking their curiosity. This conversation left a minefield’s worth of them.

Some who participate in Twitch’s popular debate culture, including more politically oriented streamers like Bonnell and The Serfs, try to be so comprehensive that there’s no room for doubt. This, however, sometimes involves directly and intentionally giving a platform to misinformation, which can backfire. Recently, both wound up separately debating the same streamer and YouTuber, Nuance Bro, who at various points has endorsed borderline-racist (or at least extremely flippantly made) claims about black people’s supposed role in spreading coronavirus and supported the idea of people afflicted with the virus taking hydroxychloroquine, a malaria drug that one study recently linked to increased death risk in covid-19 patients.

In both debates, Nuance Bro frequently pivoted to a new topic when met with information that put him on the back foot, refusing to acknowledge that he’d supported misinformation. Bonnell ultimately chose to debate him a second time after allowing too much misinformation rooted in half-truths to slip through, especially regarding hydroxychloroquine. While Bonnell more or less set the record straight during the second go around, this, he told Kotaku, was far from an ideal situation. Once misinformation is out there, it tends to travel further than subsequent corrections, and when people are presented with new, conflicting information, some dig in their heels and stand by their initial belief.

“It’s like printing a retraction, right? Who cares?” Bonnell said over a Discord voice call. “You can post retractions or corrections or whatever, but once the initial story has caught hold, that’s just kind of where we are. It becomes, like, the new reality. It’s so hard to uproot it.”

Despite not appearing to be persuaded on a large number of points in his debates with Bonnell, Nuance Bro told Kotaku in an email that the idea of platforming incorrect coronavirus information does “worry” him and that, in his own videos, he tries to take aim at conspiracy theories that have already penetrated the collective consciousness so as to minimize their spread.

There is some cause for hope where corrections are concerned, however. Recent studies have suggested that the “backfire effect”—wherein false information becomes more convincing in people’s minds when repeated—might not be as powerful as originally believed, and deliberate, targeted correction of specific misinformation could be a more effective tactic than social media companies seem to believe.

Bonnell tries to go into debates as prepared as possible, but there are limits when opponents are willing to lean on half-truths and bad faith statements, especially in a time when online conversations increasingly devolve into arguments over whose facts are even real at all.

“I think the most harmful type of speech is misinformation,” he said. “I feel like the conversations that we have as a society in the world are less and less related to what is actually happening, and it’s destroying people’s abilities to come to an agreement on anything.”

Both Bonnell and Lance pointed to the 40/40/20 rule—the idea that in these polarized settings, 40 percent of people are dug in on either side, but the 20 percent sitting on the fence can be convinced. When misinformation is involved, the question becomes whether or not that small slice of undecided pie is worth the trouble. After all, onec ideas regarded as pillars of our conception of society, reality, or what have you come up for debate, their credibility takes an instant hit. This question is especially pressing for Bonnell, who sometimes debates streamers and YouTubers with vastly smaller audiences than himself. He believes it’s worthwhile as a means of preparation because, in his eyes, it’s better to potentially struggle in front of a relative nobody’s minuscule audience than to faceplant on a bigger stage and accidentally sway a larger group of people in the wrong direction.

But even then, when somebody is peddling misinformation, they don’t necessarily need to win a debate to accomplish their goals. Modern misinformation is slippery, often designed to sop up attention through presence alone. It anticipates opposition. It does not engage on neutral ground.

“The idea is that you repeat those points until they become part of the conversation,” said Partin, pointing to debunked ideas like “partial-birth abortions” and “ballot harvesting” as terms that broke into the lexicon this way in more traditional political spaces. “You can use a structure of debate where in theory, you get to say whatever you want, you’re trying to defend your ideas, you’re appealing to this old sort of public debate ideal, but using that as a way of forcing these terms in and giving them visibility.”

The Serfs’ Lance takes a different tack than Bonnell, conducting in-person debates occasionally—as he did against Nuance Bro, whose shaky claims about both Black and Chinese people spreading the virus he cited as potentially contributing to real-world harassment and violence—but more frequently mocking the ideas and the people who spawned them.

“My strategy when it comes to the far right and alt-right is kind of to ridicule,” he told Kotaku, pointing to his tactic of briefly calling into live shows hosted by big-name far-right figures like Gavin McInnes, and riling them up. This means, on one hand, that the coronavirus misinformation pushed by these figures spreads a little further while Lance is watching their content on his stream, but on the other, it’s received by a community of people who are conditioned to find it literally laughable. At that point, it’s not just off the hallowed Debate Table; it’s theoretically below neutral ground, six feet under the loam of realistic discourse.

“When it comes to things that are just so far beyond the pale, for example, like 5G, and people burning down 5G towers, that, to me in the year 2020, just seems absolutely bizarre,” Lance said.

Lance is not alone. Many Twitch streamers casually mock 5G conspiracy theories, because it makes for good, topical content. For example, variety streamer MoonMoon had a laugh over a 5G tower he found in Minecraft earlier this month, and diet edgelord megastar Félix “xQc” Lengyel—who’s been known to watch videos about various far-fetched conspiracies with his chat for entertainment—aired a couple videos that debunked 5G coronavirus conspiracy theories during a stream last week.

Kitboga, a streamer whose in-character skewerings of phone scammers have turned him into a perennial Twitch sensation, has taken things further, comedically disarming scammers who claim to be selling coronavirus cures. But in the early goings of this project he had to be careful, because some viewers were coming into his chat to spread debunked ideas about how covid-19 isn’t any worse than the flu. And on the opposite end of the spectrum, other viewers were possible marks for exactly the sort of scams Kitboga was trying to teach them to avoid.

“I tried to be careful about not sharing the [product] name or the websites, because although I think the majority of people watching me understand that these are scams or that it’s not FDA approved, there could be a couple who are in a desperate situation or who are thinking ‘Well, I already use essential oils or alternative medicine, so why not spend $30, and maybe it could work,’” Kitboga told Kotaku over the phone.

Therein lies the difficulty of engaging with this kind of misinformation on any level: It’s ridiculous and worthy of ridicule in concept—a bad-faith tool weaponized by wealthy people who want expendable workforces and privileged people who want haircuts—but it’s also seductive. In a time of unprecedented uncertainty, some people seek comfort in simple answers to labyrinthine questions. Living with fear is hard, and it leaves many feeling powerless, angry. Painting a single entity like Bill Gates as the bad guy or taking a leap of faith on a supposed miracle cure can provide an outlet for their frustrations or take some weight off their shoulders. It by no means justifies misinformation that has an increasing number of people saying they won’t take a hypothetical covid-19 vaccine when it finally arrives—a disaster in the making—but explains why citizens of our pathologically online society can be drawn in by it. They’re not all rubes. Some are just desperate.

There is no surefire, 100 percent risk-free way to handle these ideas in a society suffering from an unprecedented public health crisis. Even platforms with strict rules in place are struggling, with inconsistency and snags in their processes allowing videos like “Plandemic” to go viral. Researchers have suggested that Facebook’s latest approach, which involves pointing users who’ve encountered misinformation in the direction of the World Health Organization’s myth-busting page about coronavirus, is too much of a catch-all, failing to correct specific claims and leaving some unaware that they even came into contact with misinformation at all. YouTube’s crackdown, meanwhile, has been spotty at best, with a recent study finding that more than a quarter of the most-viewed coronavirus videos on the ubiquitous video platform contain “misleading or inaccurate information.”

Then there’s the cultural effect of playing whack-a-mole with videos and creators deemed sufficiently offensive to warrant bans. Facebook and YouTube are now trying to catch misinformation before it can rocket to the top of their respective charts, but it’s still often a reactive process. Removal after a large number of people are already aware of a video can increase its viral appeal, stoking the fires of curiosity and motivating people to repost recordings of it or go digging on other platforms. In conspiracy theorist David Icke’s case, bans have also provided a strong marketing hook: The elites, he and his followers claim, are trying to silence him because he’s telling the truth. This is bullshit, but it fits the narrative he’s been peddling for years, and despite his preposterous reptile-people beliefs, he’s now arguably more relevant than he’s ever been. Icke and other banned conspiracy theorists have taken to milking this notoriety for all it’s worth by collaborating with other YouTubers who still have channels.

It’s not all doom and gloom, however. Twitch, if nothing else, has some possible tricks up its sleeve that other platforms don’t. Unlike on YouTube, a relatively small handful of top Twitch creators still command a disproportionate amount of total viewership and, as a result, mindshare. This doesn’t necessarily bode well for smaller streamers’ chances or the platform’s long-term health, but at least it means that there’s a more consistent set of shared community norms.

While platforms can draw lines in the sand with rules, research increasingly shows that social norms—acceptable behaviors implicitly enforced by other members of a group—have a powerful impact on users of online platforms. This is especially true on Twitch, where individual channels are governed by community moderators and community norms, which in turn help shape a broader Twitch-wide sentiment. Even in more seemingly conspiracy-receptive chats like those of Trainwrecks and Dr Disrespect, a large number of vocal Twitch users appear to be opposed to coronavirus conspiracy theories, to the point that in both of the aforementioned examples, they tried to shout down streamers who uncritically spouted them. This, Kitboga believes, might have a cooling effect on misinformation’s ability to spread via streamers.

“If some guy got on Twitch in the Just Chatting section and started pulling up charts and graphs about how the earth is flat, I feel like people would just come in there and start trolling and making fun of them,” he said.

That sword cuts both ways, though. Twitch chats are moderated by streamers and their hand-selected moderation teams, meaning that unless they have specific rules against conspiracy theories, viewers can also spread them freely in chat. That can strengthen conspiracy theories, allowing conspiratorially minded users to build on each others’ ideas. Some channels deliberately take advantage of this.

“The way [QAnon channels] set up their stream, they show their chat box on air,” said Partin. “They’re constantly engaging with each other to create these theories together in real time. So on one hand, it’s true that Twitch doesn’t have this great problem of algorithmic visibility and amplification of disinformation that other platforms do. But it’s also true that just by having that [chat] feature, it really strengthens the bonds in these communities, because they feel like they’re building this knowledge together in real time.”

Twitch’s lack of a hardline systemic approach to policing conspiracy theories could cause problems here, too. For now, these channels are small, but if left unchecked, they will likely grow. Twitch, frequently reactive in its decision-making about which channels to take action against, will then have a problem on its hands, and as we’ve seen on platforms like Facebook and YouTube, once the conspiracy genie is out of the bottle, it’s extremely difficult to stuff back in.

But Twitch is also not well equipped to be proactive because, according to two sources who spoke to Kotaku on the condition of anonymity, the vast majority of the company’s content moderation team is in-house, making it more focused than Facebook and YouTube’s unwieldy outsourced efforts, but also smaller in scale and less automated. As with elements like the platform’s front page, Twitch’s approach to this issue is more hands-on.

Nash thinks this could actually work to Twitch’s advantage, if the company plays its cards right. He believes that top streamers have a responsibility to not just avoid perpetuating bad information, but also to surface good, accurate, scientifically backed information, and that Twitch could play a direct role in facilitating that.

“Everything Twitch does is manual, and that’s why I think that one of the actual solutions to this problem might be to start approaching the problem from the top down,” he said, pointing to Twitch’s account manager system, wherein Twitch staffers communicate directly with top streamers. This system could, Nash suggested, be used to get streamers on the right track. Audiences, in turn, would be more likely to listen to their favorite streamers than, say, the ominous disembodied voice of a gargantuan corporate entity like YouTube, Facebook, or Twitter. Most Twitch viewers don’t regard streamers as embodiments of the shadow-shrouded, bony-fingered global elite; they’re viewers’ down-to-earth parasocial pals.

But this element of Twitch can easily be used to spread conspiracy theories as well. In fact, for this very reason, Twitch could be considered a hotbed of one very particular kind of conspiracy theory—namely, conspiracies about Twitch itself. The most pernicious of these tend to focus on supposed favoritism shown toward female streamers, and have taken on lives of their own over the years due in large part to the efforts of Niknam and his community.

What was once considered a fringe idea—that particular women have either blackmailed particular Twitch staff, are sleeping with them to earn favors and skirt the rules, or both—is now a commonly held belief on places like Twitter and Twitch drama hive/kingmaker Livestreamfail. During the aforementioned early-May episode of the Scuffed Podcast, Niknam himself seemed all too aware of this, suggesting that if Twitch starts cracking down on conspiracy theories, “90 percent of Twitch’s viewer base and 90 percent of Twitch’s broadcasters will be banned for the conspiracy theories of [streamer] Alinity having something on Twitch staff.”

At this point these theories are wildly pervasive, more or less embedded in the bedrock of Twitch culture. Even users who do not agree with them at least know of them. It didn’t take much to make them spread: just a big personality, time, and repetition. That suggests a tremendous vulnerability within Twitch for conspiracy theories that larger pockets of the community find compelling. As with a great many other issues, Twitch’s insistent lack of transparency contributes greatly to this.

“Twitch is like the perfect conspiracy machine,” said Bonnell. “There’s zero penetration into the company publicly or socially, you have no transparency whatsoever, a lot of their decisions appear to be either bizarre or inconsistent, and the messaging from their leadership doesn’t seem to align all the time with the actions of the company. And then when you’ve got streamers, who are ultra public-facing and also dealing with this, they can amplify any small rumor or conspiracy and hype it up and everything. So yeah, it’s a perfect breeding ground for conspiracy.”

While it’s difficult to say how you’d convince streamers like Dr Disrespect, who seems to buy into at least some misinformation, and Niknam, who doesn’t see it as his responsibility to halt the spread of conspiracy theories, to take part in a larger top-down Twitch initiative to combat misinformation, some streamers, like Nash and Twitch Safety Advisory Council member Zizaran, are already attempting to spread accurate coronavirus information to preempt misinformation. Nash has reached out to researchers and put together shows based on his findings, while Zizaran has hit the books in order to more knowledgeably counteract any misinformation he comes across. Both acknowledge that it’s impossible to know exactly what kind of impact they’re having, but in a time when trust in mainstream media, scientists, and other institutions is eroding, they can’t take their influence for granted. For some people, what they say could be game-changing, even life-saving.

“The reason I started speaking up is because this is a literal danger,” Zizaran told Kotaku over a Discord voice call. “There are 5G towers being taken down in the UK. There are people stopping their children from taking vaccines. People who are allergic to vaccines are supposed to rely on herd immunity. If that breaks down, those people are screwed.”

Partin acknowledged streamers’ individual actions and communities as potentially helpful, but still ultimately advocated for Twitch to get more directly involved by following in Facebook’s footsteps and hiring people with actual expertise in areas like misinformation and disinformation to help make relevant policy decisions. He cautioned that there are never “one size fits all solutions” for problems of this scale, but that platforms like Twitch can and should be doing more.

“It’s a big mess. And I personally think that in most cases, it is safer to take this content down. But that’s not all cases,” he said, noting that there will always be exceptions to rules, or appearances of exceptions, and that companies need to keep the public informed, or else they risk breeding more destructive conspiracy theories. “I think that the takeaway is that platforms do have a responsibility to try to limit the spread of bad information, knowing that they’re still going to generate accusations of censorship by doing so, but while prioritizing expert notions of public health and the public good. That’s what needs to be informing policies.”