Every morning, Iceland’s language planners begin their day by taking off their shoes at the communal shoe rack in their office and slipping into pairs of soft clogs. As tourists begin to fill the alleyways of downtown Reykjavik with a faint babble of English, French, Chinese, and Italian, the language planners shuffle quietly back into their fight to save the Icelandic language from extinction.

The Language Planning Department, a small government-funded office of linguists with a rotating cast of subject experts is in charge of integrating new and foreign concepts into the millennia-old Icelandic language. For decades, the department and its predecessors have invented new Icelandic words to keep up with civilizational advances abroad, from the invention of the computer (tolva) to the rise of political correctness (pólitísk rétthugsun).

Only about 320,000 people in the world speak Icelandic. Most are already bi- or trilingual, switching with ease into English or another language when abroad. The language planners’ mission is to ensure that the country’s citizens switch back to Icelandic at home. A vibrant national language, they say, is as vital to Iceland’s sovereignty as the roads that connect its moonscape plains and coastal towns.

Digital extinction

More people around the world are literate than ever before in our species’ history—and yet a mass extinction threatens the world’s languages. In a phenomenon known to linguists as “digital death,” 7,000 languages globally are at risk of falling into disuse because they simply are not that useful online. Netflix, for example, does not offer Icelandic subtitles—much less Wolof or Welsh. Wikipedia offers only about 47,000 articles in Icelandic, compared to more than 47 million in English.

Emerging speech recognition technology could narrow the language funnel even further. Voice assistants Cortana, Alexa, Siri and Google Assistant speak only 22 languages in total.

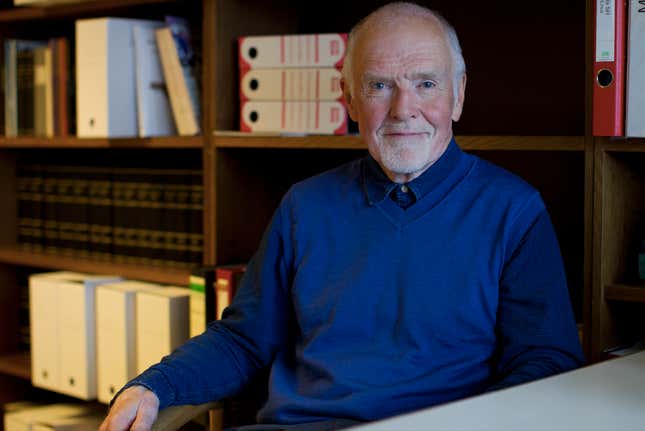

“Many have been concerned for the last 10 or 15 years that we are losing this battle in language technology,” says Johannes Sigtrygsson, a researcher and dictionary specialist at the Language Planning Department. “That English will become the language of these smart things, like Alexa and Google, things that you talk to. If you order them to do something, you will only be able to do it in English!” It’s the prospect of speaking a foreign language to devices in your own kitchen or bedroom that make this linguistic conundrum seem particularly distasteful, his examples suggest. Imagine coming home and having to look up the Martian word for “half-and-half,” because that’s all your supposedly smart refrigerator understands.

And so the language planners, led by linguist Ari Páll Kristinsson, are working furiously to match every English word or concept with an Icelandic one—giving young Icelanders no excuse for depending on loanwords learned online.

A onetime colony of Denmark, the island nation’s organized resistance to linguistic imperialism dates back centuries, and its methods are well-established. For Ari personally, the fight to make technology accessible in Icelandic dates back decades. In a 1998 interview with the Los Angeles Times, Ari criticized Microsoft for “destroying” Iceland’s language preservation efforts by refusing to translate Windows into Icelandic.

The book of bananas and grapenuts

On the day’s agenda when I visited the Language Planning Department, housed in Reykjavik’s the Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies: A retired doctor was drafting a list of new foreign medical words to add to the Icelandic lexicon. Someone was carrying out research on the historic names of places in Iceland. In the afternoon, a boisterous, all-women committee studying new terms related to leisure led by Ágústa Þorbergsdóttir, would punctuate the calm office environment with bursts of laughter.

Ágústa is the Language Planning Department’s project manager, and oversees the many professional committees that convene to discuss terms needed in their industries. Like everyone I meet in Iceland, she understands English easily—though she prefers to respond in Icelandic. Before joining the Language Planning Department, she worked at another cultural protection agency: the Icelandic Naming Committee, which rules on which baby names are sufficiently Icelandic to be permitted and which are not, sometimes to great controversy.

Every language captures unique concepts that simply don’t exist elsewhere, she reminds me, which might be reason enough to fight for their preservation. In Icelandic, the word Sauðljóst describes a hazy moment just before dawn, and literally means: “the time of day when there is just enough light to see your sheep.”

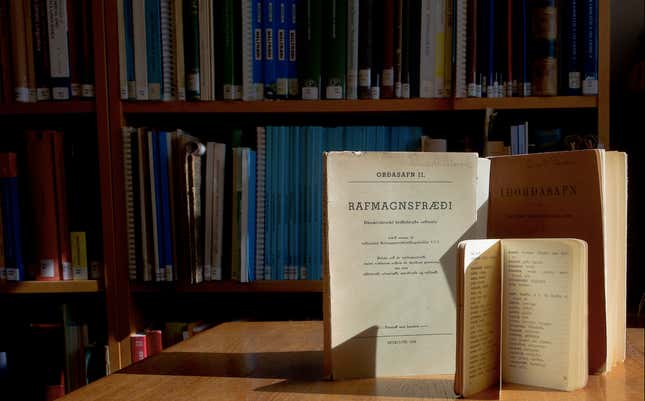

In the Department’s sunny conference room, she showed me some of the original texts created by the Planning Department’s predecessors decades ago: faded books of translation for fields as diverse as electrical engineering, sailing, and even grocery shopping.

The country’s first-ever “wordbook” was created in in 1927 with funding from the government: Sized for a man’s breast-pocket, it was intended to teach Icelanders newly-invented words for foreign products like grapenuts. (The book’s suggestion for bananas was bjúgaldin, aka “fruit that bends”—and has since been dropped in favor of the simple banani.)

How to invent a word in Icelandic

The Language Planning Department invents new words by reinvigorating or combining archaic ones. “The ideas was that if you used the native stems, then it would be easier for common people to understand the new ideas,” says Johannes, the dictionary specialist. Thus “television” is translated as sjónvarp,which combines the ancient words for vision (sjón) and throw (varp)—aptly describing the way that TVs send images to viewers.

Every language has unique fossilized compound roots, obsolete grammars, the sediment of past pronunciations and local lore that contain ancient knowledge about medicine, culture and the natural world. An Icelander hearing the unusually poetic word tolva for “computer” also hears the faint ring of its ancient root words: tala for “number” and volva for “a female seer.” The Icelandic term for “midwife” (ljósmóður) combines “mother” and “light,” literally “mother of light.” While nearly every Icelander probably understands the same words in English, the foreign words offer no such colorful undertones.

Knowing the geology of a word also allows its speakers to better understand the ideology that shaped it. The ancient word for “homosexual” in Icelandic, for example, once described a person who had lost their sex, or was drifting away from it—literally disoriented. To add further insult, one of the words in the compound, villingur, also implied someone who is ill-behaved. Having identified that history in the word, Icelanders have stopped using it altogether, in favor of samkynhneigð or samkynhneigður.

Outside the department, Icelanders have used the same compound method to make their own translations of global vernacular. Hrutskyring, the Icelandic word for “mansplaining,” substitutes the Icelandic word for “ram” where the English is “man.” (Icelanders rarely miss an opportunity to insert a sheep pun.) The DIY compound neologism mammviskubit (mother guilt), refers to the guilt that modern mothers might feel when distracted from parenting by their phones or work. There is no equivalent term for fathers.

The Department is there to help Icelanders of all stripes invent any word they want. “I’ve just got this new gadget to sell. What should I call it?” is the sort of common question that the Language Planning Department receives, says Ari. New words used to be announced in the newspaper. Now the department’s inventions are gathered by topic and published as softcover glossaries, and added into an digital public “wordbank,” which they hope citizens will consult. “Sometimes they don’t like the existing word, or they don’t like the connotation of the word. Everyone is free to create a new word,” he says.

The department is small and its work is mostly scholarly. But if the words they invent to describe modernity catch on, they will be key to a larger language preservation project: The government has dedicated the equivalent of millions of dollars to develop vast linguistic databases, called “corpora”, that can be used to train computers to speak and automatically translate Icelandic—so that no Icelander ever has to use a foreign language if they don’t want to.

A democratic language project

Iceland is a famously bookish culture. In the Nobel-Prize winning novel Independent People, (1934) by Icelandic author Halldórs Laxness, impoverished shepherds in the early 20th century trade elaborate verse, rich in words even when food is scarce. In more recent times, Iceland’s fascination with all things literary might have something to do with the country’s famously dull television. Until the mid-1980s, the only broadcast available in Iceland was state television—and even that wasn’t available on Thursdays and during the month of July.

Whatever the cause, seemingly everyone in Iceland cares about language. In fact, it was not the country’s literati, but its researchers in science, tech and industry who needed new words most desperately over the past century, for example in the fast-changing fields of wireless telecommunications, shipbuilding, and electrical engineering. The Electrical Engineers committee has been the most consistently active language committee since its founding in 1941.

According to legend, it was a single Icelandic engineer working at Google who originally snuck Icelandic into the early Google Translate options. Later, another Icelandic researcher personally championed Icelandic as a language to be included in Google’s speech recognition software: Trausti Kristjanssen, whose father, a biomedical engineer, created Iceland’s first computer dictionary.

“It goes back to the Viking culture—being a good poet was as important as being a good warrior,” says Trausti, of his own deep interest in the language. “I think this is why the early Icelanders wrote the sagas. Because it was an important part of manhood.”

How to teach a machine Icelandic

In 2006, Trausti was working on Google’s voice search in handful of languages. It was slow going, due to the enormous cost and effort required at the time to make a computer understand human speech. “We had people working for 15 years on the peculiarities of French—pronunciation, grammar, syntax rules,” Trausti recalls. “I said we should do Icelandic, and everyone laughed.”

Now Trausti can laugh (hlátur). Google did eventually create voice search in Icelandic, as well as SMS dictation, thanks to a realization that could save languages across the world: Instead of devoting costly human resources to transmitting all of the knowledge and rules that constitute a language to a computer, Google would let the machines learn on their own—much like human children do.

Trausti’s team, led by data scientist Pedro Moreno, realized that machine learning could make the process fast enough to add all kinds of languages, with far less effort or investment than originally thought. “All we needed was a huge amount of data and not experts,” says Trausti. As a pilot, Google recruited some researchers from the University of Iceland to help collect the data with open-source tools. In 2009, they sent cell phones to various workplaces in Iceland, and asked those organizations to collect phrases from all the workers, for a total of about 250,000 unique utterances. Icelandic voice search came out the next year.

Trausti, now a research manager in speech recognition and audio processing at Amazon, continues to work with the University of Reykjavik on language technology for Iceland. But he declines to go into detail about what that might mean for secretive Amazon, telling me, “I can only say that I’m pushing for Icelandic at Amazon in any way I can.”

The success of Google voice search through machine learning suggests a huge opportunity for even the most esoteric spoken languages. Keenly aware of the technological promise, Iceland plans to make its language databases available to foreign tech companies, free of charge. The hope is that making the data free will incentivize more companies to teach their AI Icelandic.

But it’s not clear that even free data will ultimately offer enough of an incentive for Big Tech to develop products and services for a language with comparatively few speakers. Seven years after the team’s breakthrough with voice search, Google’s voice translation service Interpreter does not speak Icelandic. Nor is Icelandic available for the voice-operated Google Assistant. While the company says it continues to test new languages for Assistant, Icelandic is not one of them.

The human factor

The fight to keep the Icelandic language in circulation should not be confused with isolationism. Most Icelanders are at least bilingual, and few would argue that this isolated rock in the middle of the Atlantic would benefit from closing its doors to the world’s languages. Rather, what people like Trausti, Johannes and Agusta fear is becoming isolated in time—losing their connection to the past 1,000 years of Icelandic life and literature.

Johannes, the dictionary researcher, wistfully describes an Icelandic “language community” that is actually far greater than the island’s current population—if you count all the people who’ve ever spoken the language. “Strange thing that we [Icelanders] are so few,” he says. “But we are not so few when you think about it. All the people that have ever lived in Iceland are part of one language community and we understand all Icelanders that have gone before us. So that should be important.”

Most young people I met pooh-poohed the idea that their language could disappear, and one or two gently mocked the Language Planning Department’s attempts to centralize word-creation. However, the very youngest Icelander I met, a 12-year-old teenager riding his bike along a desolate patch of rural Icelandic coastline, did confess that he did sometimes forget basic Icelandic words—including the word “lunch”—to the consternation of his mom. He had learned his English from Grand Theft Auto and Friends, he said.

Even if the all the world’s tech companies agreed to offer Icelandic options, there is a human problem: Young Icelanders have to want to speak Icelandic, and they have to have reason to speak it in their own country. Meanwhile, skyrocketing tourism is bringing foreign languages to even Iceland’s most remote crags, glaciers and black sand beaches (PDF, pg. 17), prompting complaints that Icelandic just isn’t that useful in real-life encounters, either.

But while humans may not be as quick to learn as machines, they are at least easier to persuade. Zahra, an Afghan refugee who moved to Iceland when she was 19, tells me that she stopped using English soon after her arrival. “Icelanders are very kind to us as strangers, and when I was using my first Icelandic word, I felt that ‘Ok, they get real happy when we speak Icelandic,’ she says. “And I wanted to just make them happy.”

Seven years later, she runs a business as a professional interpreter from Persian and Dari into Icelandic. “When I am talking with my friends who don’t speak Icelandic here, some say, ‘Why do we have to learn Icelandic, when everyone here can speak English and nowhere in the world can we use Icelandic?’” she says.

“And I say, it makes you special to speak a language that nobody can speak!” Then she corrects herself: “I mean, not nobody. But very few.”