Armed with fresh survey data and a counterintuitive thesis, a new Brookings Institution study released Wednesday makes the compelling case that Mitt Romney's Mormon faith, long pegged by pundits as a political albatross for the candidate, won't actually hurt him at the polls in November — and it could even help.

But the study's most telling revelation is relegated to a side note: Even after four months of Republican primaries, Americans still know virtually nothing about Romney's faith — and for many, their opinions of the religion remain highly maleable.

According to the study, a full 82 percent of respondents said they knew "little" or "nothing" about Mormonism, and researchers found that feeding them even a couple sentences of basic information about the church's beliefs had the ability to swing wide swaths of the electorate in terms of their support for Romney.

In the case of this particular survey, the headline-ready finding is that — among conservatives at least — such information actually increased support for the candidate. But the fact that it has any notable effect at all should be enough to give Romney's campaign pause. After all, the electoral consequences of Romney's religion could ultimately be determined by what voters learn about Mormonism in the coming months. And so far, Romney has remained largely unwilling to engage on that topic — leaving others to define his religion.

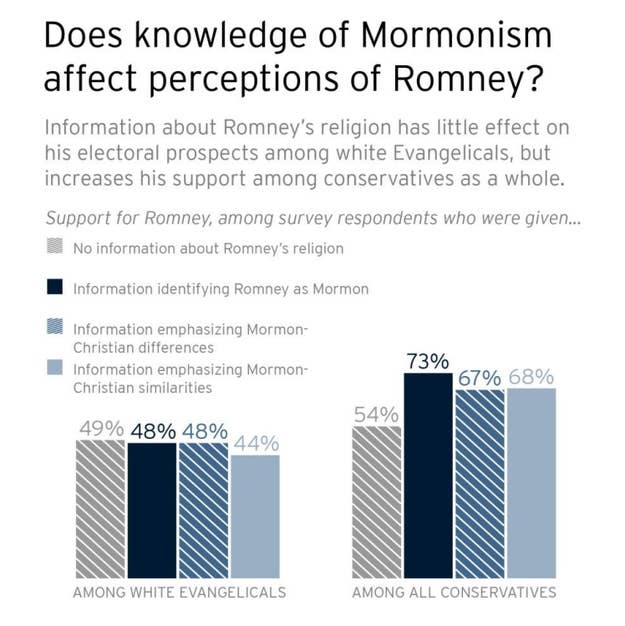

Researchers Matthew Chingos and Michael Henderson gathered their data by conducting an experiment. They surveyed 2,084 online Amazon users, 16 percent of whom were white Evangelical Christians. The respondents were divided into four different groups, and each set was given different information about Romney's religion — then asked if they support him.

For the first group, Romney's religion was not identified at all; for the second group, it was, but without any additional information; the third group was told that Romney is a Mormon, and that Mormons believe in Jesus Christ and the Bible; the final group was given a three-sentence primer on Romney's faith, including a brief explanation of the Book of Mormon and founding prophet Joseph Smith.

The study found that conservatives who were told about Romney's faith were much more likely to support the candidate:

As David Leonhardt at the New York Times points out, the results could be skewed by respondents not wanting to seem prejudiced. But if anything, this study would seem like good news for the Romney campaign, in theory.

The reality, though, is that voters won't be given the same evenhanded summaries of Mormon belief that these survey respondents got. Over the next six months, Americans are going to receive a widely-amplified education on Mormonism, and the curriculum — along with the few tidbits of information that penetrate the public consciousness — will depend largely on he teachers: Namely, the news media.

The parts of Mormonism that will become the subjects of front-page features and network newscasts will likely dovetail with the broader stories that are dominating headlines. For example, if a Trayvon Martin-like tragedy gets national attention in October, people may walk into the voting booth thinking about Mormonism's complicated legacy on race. If the mommy wars flare up again, Americans might learn more about Mormon teachings on family. And any rogue political surrogate has the power to go on CNN and launch into a viral, off-message rant that throws a spotlight on some esoteric LDS doctrine or practice.

Chingos and Henderson acknowledge in their paper that the media's approach to Mormonism is unpredictable.

"In the past four months, the New York Times alone has published articles on Mormon history, policy positions, and even cuisine," they write. "Americans are likely to learn much about Mormonism between now and November, and it is unclear how, if at all, that information will affect the outcome on Election Day."

None of these issues is likely to define the election — which will ultimately be about the state of the economy — but they do have the ability to define Mormonism in the minds of many voters. When it comes to this young, unfamiliar faith, the American public is basically a blank slate.

And as this study suggests, what ends up being drawn on that slate could have profound electoral consequences for Romney.