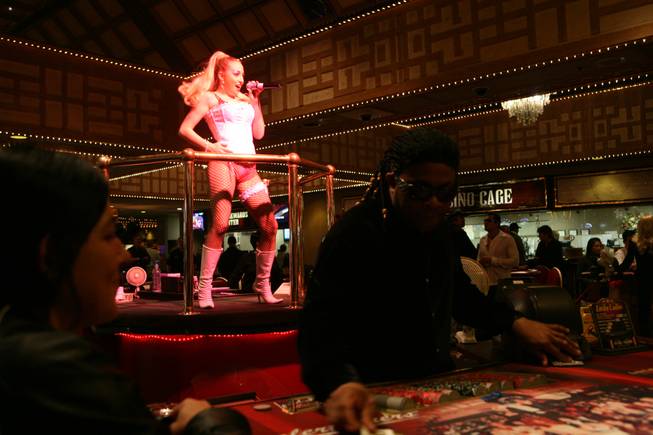

Nichole Shields, 23, a UNLV student by day, works as a Madonna-impersonating “dealertainer” at Imperial Palace by night. Her shift there ends at 4 a.m.

Monday, March 10, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Beyond the Sun

Her eye shadow sparkling, her lips painted a bold red, Imperial Palace “dealertainer” Nichole Shields high-fives players at her table who have just won a hand of blackjack.

It’s just before midnight, and around her on the casino floor, dealers, tourists, locals, pit bosses and long-legged cocktail servers waltz to Vegas’ music: cheers and laughter, chips clinking, the dizzying sounds of slot machines singing.

A UNLV student by day, Shields, 23, impersonates Madonna by night. She’s wearing white stiletto boots, fishnet stockings, a white corset and a long blond ponytail.

When her shift ends at 4 a.m., she’ll get some sleep, head to school for early-afternoon classes, then catch a nap. About 8 p.m., she’ll return to work as Madonna.

In any given week, Shields spends more time at work than at school. A part-time student, she’ll be 25 when she graduates — an anomaly at top-ranked universities, but typical in the Las Vegas Valley, where many students hold full-time jobs.

Splitting time between work and school can tempt students to stretch out their studies or drop out of college in any city. But some educators believe that problem is more prevalent in Las Vegas, where local companies, notably hotel and casino operators, create plenty of opportunities for workers such as Shields to earn good pay without a bachelor’s degree.

It’s difficult to tell exactly how much the job market influences students’ decisions. What is known is that more than a quarter of UNLV’s undergraduates are part time, taking fewer than 12 credits, and that contributes to the university’s low six-year graduation rate of 46 percent.

Administrators would like to see more people finish college in a timely manner, but they know little about why students leave the school or take so long to graduate. UNLV will begin surveying students this year to get more information about why students drop out and next year will survey students about how many of them work.

When students don’t earn a degree within six years of enrollment, that hurts a school’s national ranking.

Students such as Shields, however, feel no urgency to finish college. In their eyes, the hospitality industry presents opportunities, not problems.

“I like that I don’t go to school full time,” she said. “I’m kind of tired of school. To be honest with you, I feel like I’m never going to get done.”

• • •

Two miles west of UNLV, the resorts lining Las Vegas Boulevard glimmer and glow. In the night sky above the university, the roaring 737s that ferry tourists in and out of the city outshine everything — the stars, the planets, the man-made satellites crawling in their orbits.

Leisure and hospitality, the region’s most visible industry, employs more than a quarter-million people in Clark County. And the armies of bouncers, concierges, housekeepers, limousine drivers, valets and waiters that serve the valley’s visitors count among their ranks many students — and college dropouts.

At the College of Southern Nevada, where three in four students work, administrators say the valley’s job offerings hamper counselors’ efforts to persuade students to stay in school.

“We compete with the job market,” said Frank DiPuma, CSN’s director of institutional research. “If your schedule changes, then you can’t balance both (school and work) anymore and you drop out.”

That dynamic, though not unique to Las Vegas, is more pronounced here than elsewhere, DiPuma said.

“If you graduated high school in San Jose and you wanted to get into the job market, you would have to look around, and look pretty hard, to get into the same kind of service jobs that we have here,” he said.

Still, despite anecdotal evidence that students prioritize work over school, determining how much Las Vegas’ economy influences graduation rates is difficult.

UNLV, for one, doesn’t keep track of how many hours students work, where they work, or even how many of them work.

Some curious trends emerge from what officials do know. Many UNLV dropouts have a good academic record, said Rebecca Mills, vice president for student life. An unusually large number leave school late in their college careers.

Gayle Juneau, executive director of academic advising at UNLV, said the top reason students give counselors for leaving school is family-related responsibilities such as caring for children or aging parents.

Making money can be part of supporting relatives. But that doesn’t mean everybody’s working on the Strip. Many students labor at movie theaters, doctors’ offices and other venues typical of any city, Juneau said.

To investigate why students leave UNLV, administrators plan to begin systematically surveying dropouts this month about the reasons for their departure. The school also is scheduled in spring 2009 to conduct a survey that will explore, among other issues, how much students work.

• • •

Professors at local colleges like to joke that students make more money than their instructors do. Young people, too, gab about the gigs they land.

An aspiring teacher, Shields said her pay, tips included, tops that of an entry-level Clark County teacher. She is eligible for health benefits and a 401(k).

Likewise, Niccole Maturino, 23, a part-time CSN student, takes home a good bit of money as a full-time spa receptionist. Though her parents would have bankrolled a full-time education, she thought gaining hands-on experience mattered more than earning a degree quickly.

And Jared Rose, 21, a Centennial High School graduate who dropped out of UNLV after less than one semester, founded a small company that promotes parties at nightclubs, bars and other venues in town.

All three say they might have finished college more quickly in a city with fewer exciting job prospects.

That sentiment is bad news for academics such as UNLV President David Ashley who believe students benefit from graduating in a timely manner. Life is unpredictable, and a higher education gives workers flexibility to switch careers and relocate, he said.

And even in the hospitality industry, lacking a degree can be a barrier to success.

Though high school graduates “hear through the grapevine” that people make $70,000 parking cars or six figures working banquets, jobs for people without a college education are less lucrative than rumors suggest, said Chris Cappas, vice president of employment and training for Harrah’s Entertainment in Las Vegas.

“To really be in the high-paying tip jobs,” Cappas said in an e-mail, “it takes seniority — in some cases years of experience — and luck.”

With few exceptions, jobs at the director level and above go to college graduates, who tend to have better analytical and communication skills than less-educated peers, said Jonathan Halkyard, Harrah’s senior vice president, chief financial officer and treasurer. He sees skipping college in favor of a $20-an-hour job as shortsighted for an intelligent young adult.

Some students are reaching similar conclusions on their own.

Maturino, who wants to become a manager in the hospitality industry, plans to transfer to UNLV to get a bachelor’s degree.

Rose, who wants to return to school this summer, sees completing college as a way to show future business partners “I can finish something that I start.”

Shields said that though she loves her job, “it can’t be a permanent thing.” Her work, with all its dancing and standing, will eventually wear down her body, she said.

• • •

In many ways, beneath its whimsical facade, Las Vegas is a land of dreams put on hold.

Juneau said that over and over, students who left school thinking a job they’d snagged would be the ticket to money and a good life return years later, regretful.

DiPuma sees the same pattern at CSN.

“Kids get into the labor market and they stay in the labor market for five, six, eight years. Then they begin to realize, ‘My mind is turning to hamburger and I hate parking cars. I need to go back to school to learn something.’ ”

Ashley said college staff must help students understand the value of a degree before other opportunities lure them away. He hopes to raise UNLV’s graduation rate to at least 65 percent in coming years.

Though the university has historically been a haven for part-time students, the emphasis in the future, Ashley said, will be on full-timers, who are more likely to flourish academically and participate in campus activities.

“It’s up to us to say we have expectations of the students and ourselves that are different from what (they’ve) been in the past,” he said.

In 2005-06, UNLV had a larger proportion of part-time students than 13 of 16 universities of similar size, selectivity and research level, according to a database run by the Institute for College Access & Success.

The state or community colleges, Ashley said, are better places than UNLV for many students not interested in full-time school.

Students say scheduling more classes and adding academic advisers would help keep more people enrolled.

To make UNLV more attractive to students, officials plan to launch a center next year that will connect freshmen to services such as tutoring.

The university has a new recreation center and student union. State-of-the-art buildings for engineering and urban affairs disciplines are to open this year.

But for some students, those improvements may not be enough to outshine the valley’s billion-dollar resorts and the paychecks they offer.

Maturino, Rose and Shields said they don’t regret detouring off the classic path to a bachelor’s degree. Their post-high school lives might in fact be the envy of many other people their age, some of whom graduate from college only to find themselves toiling in work they hate.

Maturino has put her earnings to use vacationing in Indonesia and Italy.

Rose said the perks of his job include hobnobbing with celebrities such as socialites Nicky and Paris Hilton — “and at this age, who would say no to that?”

And Shields, dealing cards on a recent night, seems happy too. Her eyes sparkling, she chats up the players at her table, singing along as a fellow dealertainer performs Aretha Franklin’s “Freeway of Love (Pink Cadillac).”

Tomorrow afternoon, Shields has a test to take. But for now, as Madonna, she is dancing.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy