You can prepare for a Bob Geldof interview, but you cannot prepare for Bob Geldof himself. Not that he isn’t how you imagine: he is, but more so. Taller, louder, funnier, better read, more sweary, more informed, more opinionated. More everything. He rarely draws breath. He fires off stats about the planet’s resources (“Humans will need 1,700% of the planet’s resources in 80 years”), and the energy drain that is Google (“Every time you search for something on Google, you use as much energy as driving a car 65 metres”). He berates the BBC’s Africa coverage (“They only want the noble primitive version”), then switches to my career, though we’ve met only once before: “Telly’s where the money’s at, Sawyer, get with the programme!” If you were to draw a cartoon of us during this interview, I would have my hair blown back, as though facing a hurricane.

We are at his record company, in a stupid/trendy meeting room, at a table for 16, furnished with beverages. Geldof is wearing sunglasses. I ask him if he’s going to take them off and he peers over them at me, prodding at his right eye.

“I’m getting a stye,” he says. “And I wanted to be all twinkly for this interview, so I went into Boots to get some stuff for styes and they don’t make it any more because the new thinking is, the stye will just go on its own!” He uses the same tone about this as he does about Google: utter outrage. “They said use Optrex, so I left immediately and I went into Superdrug and they said the same. Unbelievable. So I put Zovirax [a fairly heavy-duty cold sore treatment] on my eye.”

You idiot! I say, and take a look. His eye seems fine, if crumpled. With his tufty grey hair and skinny legs, he doesn’t look healthy, but he looks exactly as he should: like a hungry mongrel dog. Anyhow, his style is irrelevant. With Geldof, it’s all about his personality. When he’s in full flow, which is most of the time, the conversation flies past like a speeding truck. You just grab on by your fingernails. Oddly, it feels as if Geldof does, too. He slightly loses control of things when he’s speaking: bashes his hands on the table, swooshes his phone to the floor. He keeps getting up to pour himself a black coffee. Every time he does, he can’t remember which of the three jugs contains coffee and flails between them. At one point, he pours himself a cup of hot water. Without breaking flow, he just spins around and chucks the water into the bin, then fills up and continues.

We are here to talk about the Boomtown Rats, which some might say is the least interesting thing about Bob Geldof. His life in music has long been overshadowed by his other lives, which we will come to: his anti-poverty campaigning and, more tragically, his personal life, particularly the death of his ex-wife Paula Yates from a heroin overdose in 2000 and, in April this year, the death of his daughter Peaches in similar circumstances.

But the Geldof story began with the Boomtown Rats and last year, for reasons of “age, curiosity and cash”, the Rats re-formed. They played at the Isle of Wight festival and were a triumph, so they did a few small dates and released an album of their old tunes. Now, they’re about to tour all the places they didn’t get to last year, and release another, slightly different album of their old tunes. Some of the band have mortgages to pay.

The Boomtown Rats formed in Dún Laoghaire, a Dublin suburb, in 1975. They were influenced by R&B initially, the storming sounds of Dr Feelgood; but then punk happened, which they loved, and they got mixed up in that. Geldof tells a funny story about doing a tour of schools with Talking Heads and the Ramones in 1976. Each band tried out as headliners, but “no one could follow the Ramones”, so it fell into a natural order: Talking Heads, Boomtown Rats, Ramones. All playing to schoolchildren in layered hairdos and flares.

Did the kids go mad? “No. They could not get their heads around any of us. Especially not Talking Heads. They just stared and stared.”

The Boomtown Rats never fitted properly into punk – punk was too snobbily English to accept these young Irishmen in their over-wide trousers – but they did very well in the charts. Famously, they knocked John Travolta and Olivia Newton-John’s Summer Nights off the No 1 slot with Rat Trap (with utter seriousness, the Rats all tore up a picture of Travolta in front of the TOTP cameras – ah, the days when pop mattered). Their songs were new wave as opposed to punk: overproduced, with uncool piano and saxophone. But they were hooky and well constructed, plus their lyrics were about something. They told stories.

This is another reason why Geldof agreed, last year, to re-form the Rats. He feels that a lot of what the songs were about is still relevant now: young people without prospects in the UK (Rat Trap), US kids going mad and shooting their classmates (I Don’t Like Mondays), Ireland’s paedophilia problem being covered up (Banana Republic), people’s sense of alienation from those in power (Lookin’ After Number One). It wasn’t he who re-formed the band, though: the Isle of Wight festival asked if they wanted to play. So the band – four of the original six, two have “proper jobs” – met up for a rehearsal, to see what would happen.

“For the first hour we were terrible,” Geldof says. “Someone said ‘Stop’, so we had a break. And we went back afterwards, somewhat ruefully, because we thought it was over, and something happened. Garry [Roberts] attacked his guitar, and we did Lookin’ After Number One. And we were ferocious.”

He felt fine about playing in front of a crowd, because he’s never stopped performing as a solo artist, his career enjoying an uplift with his well-regarded last album, How To Compose Popular Songs That Will Sell. Still, the day before the Rats were due to play the Isle of Wight, he went on stage with a big German band called Die Toten Hosen (the Dead Trousers), to get the feel of performing in front of thousands. Then he helicoptered to the Isle of Wight (helicopter borrowed from “a mate”), which kept him in the rock’n’roll mood. Also, in order to get into “Bobby Boomtown” character, he got a Brick Lane tailor to make him a fake snakeskin suit (as worn on today’s cover). As soon as he slithered into that, he was there.

These days, he says, the Rats’ audience is the middle aged and their kids: “Thirteen-year-olds who’ve been made to listen to us by their dads.” When I was their age, I liked the Boomtown Rats a lot, so I imagine they enjoy it. “Well, that sound hasn’t really changed, has it?” he points out. “It’s all pretty simple stuff musically, but it’s not about that, it’s about how you play it, the aggression, the energy. The racket. And the rackety-ness, how it might fall apart at any minute. There’s a lineage for that noise, it’s not hard to understand. And, though I say it myself, we’re a bloody great live band.”

Though the Boomtown Rats were big for around five years there was, he says, something about being successful that didn’t sit well with him. He wrote about it in the Rats song Wind Chill Factor (Minus Zero), and quotes the lyrics: “It’s one of those days when I don’t like myself… I’ll slip beneath these sheets and shiver here awhile.” Fame was all he wanted, growing up, but when it came to the reality, there were responsibilities he hadn’t expected. Interviews. Duties. Record company people telling him he had to write a hit. She’s So Modern, which was about TV presenters Magenta Devine, Paula Yates, Mariella Frostrup – “these amazing girls on the scene” – was constructed in order to satisfy such demands, so he never really liked it.

We talk about singers who successfully negotiate getting older. He loves Leonard Cohen and Loudon Wainwright III: “I can’t believe he doesn’t get more kudos”; he thinks Van Morrison can still pull something out of his hat, Bob Dylan “not any more… Though I would never put myself anywhere near any of them, don’t get me wrong.” He has a big ego – he’s a lead singer – but is clear-eyed about his strengths and weaknesses. Music is his first and longest lasting love, but he will never reach the heights of his heroes. Still, he has what none of those other songwriters has: another job.

As a consequence of what we might call his extreme fundraising – most memorably 1985’s Live Aid (£150m raised) and Live 8 in 2005 (encouraging G8 leaders to double their overseas aid) – Geldof has saved thousands of lives. And because of this, he zooms about in the upperest of echelons. He refers to important people by one name: not just Bono, but Sergey, Larry (Brin and Page: Google), Gates (Bill: Microsoft), Zuckerberg (Mark: Facebook), Kofi (Annan). When he’s not making music, much of his time is spent hopping around the world making keynote speeches. He does this at the South By Southwest festival, at international business conferences, even at a launch for smart meters. A few years ago, he started a private equity company, 8 Miles, that invests only in African projects, the idea being that the investors make money not in a couple of years, but a long time hence. He works with One, the foundation set up by Bono that campaigns to end poverty and preventable disease, mostly in Africa. He’s extremely busy, but that’s how he likes it; he needs a lot going on, and he needs to be organising it.

Geldof is all about the big idea: the big move, the historical sweep. He has no time for press gossip, for the silliness of Twitter, the constant chirruping of modern tech. Recently, he put a ban on morning emails at his highly successful TV company, Ten Alps. Everyone who gets in touch gets a message saying that their query will be dealt with after 2pm. (“I employ these people to have ideas,” he says. “What’s the point in having a company of secretaries?”) His phone is a Nokia 6210: “The AK-47 of mobile phones.” He likes it because it gets a signal anywhere and its battery lasts for ages. The ringer doesn’t work, which he likes even more. You have to text him to say you’re about to call. He has an unshakable focus on and belief in what he thinks is important.

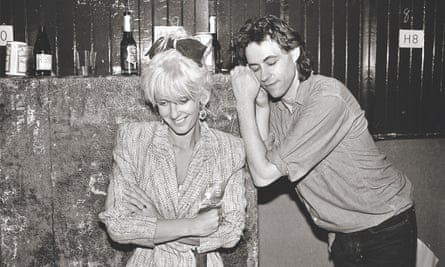

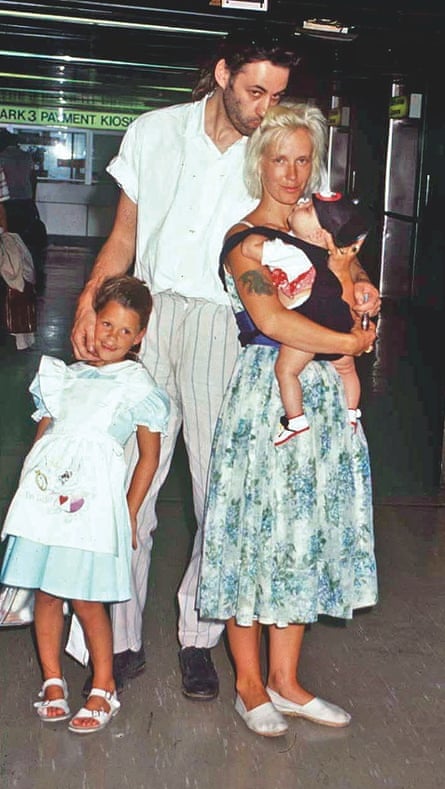

And then there is the drama of his personal life. This has been a constant since the late 1970s, mostly because of his and Paula Yates’ relationship: “We were like the cheap alternative to Rod and Britt.” It escalated in 1995 when Yates left him, after 19 years and three children together, for INXS singer Michael Hutchence. The saga – the press hounding, drugs and custody battles – culminated in both Hutchence’s and Yates’ death: his from suicide, hers from an accidental overdose of heroin. Bob and his family took in their daughter, Tiger Lily, formally adopting her in 2007.

He has had quite enough tragedy for anyone to handle. And he does handle it, though he’s taken to referring to it as the “Geldof thing”, or “this ridiculous name”, like it’s a fairytale curse. Still, just last year, he said in an interview that he had been happier in the last decade than he ever has been: settled with his long-term partner Jeanne Marine, his career going fine, his daughters, Fifi, Peaches, Pixie and Tiger Lily all doing well.

But then in April, Peaches, the second eldest of his daughters, was found dead at her home in Kent. A charismatic, defiant, clever social butterfly, a writer and TV presenter, Peaches seemed to have found happiness when she married and became mother to her two sons, Astala and Phaedra. She certainly wiped the floor with her opponent Katie Hopkins when she appeared on TV a few months before her death, promoting attachment parenting. Her sons were both under two when she died; she was only 25. “We are beyond pain,” wrote Geldof at the time. “She was the wildest, funniest, cleverest, wittiest and the most bonkers of all of us.”

We skirt around Peaches’ death for a good half of the interview, but it can’t be avoided. When I ask how he is coping, Geldof’s rat-a-tat patter stops.

“It comes and goes,” he says, after a pause. “Plane rides don’t help, because you’re on your own. I travel with my mate, who’s my agent, and we play Scrabble, but in between choosing the words, you’re left there, with it. So usually I try to write or read. Anything. But even then, it will assail you. And it is an assault.”

Earlier this year, Geldof appeared on Lorraine Kelly’s daytime TV show to talk about Peaches. “I did it because of the thousands of people who wrote to me after she died. I thought, I’ll just address them directly, to say thank you.” He said to Kelly, and he does to me, that he has to hide from the paparazzi when he “buckles”, rush down an alley, so they don’t get a shot of him crying.

“Peaches had such an impact, you know,” he says. “I didn’t really understand why… I could understand with Paula, because she’d been a figure on television, and was very different from what was expected of a girl at that time. And didn’t give a toss, and was very bright and beautiful.

“Peaches was super-bright, too. Maybe over-bright, and could wind people up the wrong way… I dunno. I got a letter from a New York cab driver who, when he heard the news, had to pull over and go and have a beer to steady himself. You think, ‘Why is that?’ The people, from 14 up to 28, if you read their letters – there’s genuine sorrow. The impact she had on them. The impact of her tiny little life.”

Geldof only reads the Financial Times, so he didn’t notice the change of tone in the press when the inquest revealed that Peaches, like her mother, had died of an accidental heroin overdose. (Initially, police said she had died of natural causes.)

“I wasn’t at the inquest,” he says, “but obviously, I knew what was going on. It doesn’t make any difference to me, the pain and dismay is just as great. With addiction, there are some who say that it’s a disease, others that it’s voluntary. I think that people are a certain way. The older rock’n’roll guys who managed to kick the habit, they become obsessive about health or something, there’s part of their nature that is compulsive. I would imagine that it’s partially genetic. And if it’s triggered once, then it’s very hard to stop.”

It’s like a switch that’s always on. “Yes, if it’s on, it’s on. Having said that, I’m sure there’s a part of you that suspects it’s on, and therefore you should steer clear of the triggers.”

He does not have an addictive nature himself. Recently, he got into smoking a pipe: Jeanne Marine bought him one and he loved the taste of the tobacco and the way the pipe “gave me this unwarranted air of sagacity”. After a while, though, he thought he looked like an idiot, “so I just said, ‘Forget it’, and gave it up instantly”.

He took cocaine in the Rats’ early days, when they would arrive to do record signings in America and nobody would turn up. One of the Rats’ US contingent – “like Artie Fufkin” (from Spinal Tap) – would rack out lines of coke as an apology. “But I was always too mean to buy it,” he says. “Also, ultimately, I didn’t like it. It made me… too wired, too nervy. The feel-good lasted a couple of seconds, then I’d be talking to the Artie Fufkins, and they’d be saying, ‘This was a disaster, it’s my fault, but I’m going to break this record, you made one of the great records of all time.’ And I’d agree, going, ‘Yeah!’ And the sane part of you is going, ‘Are you listening to yourself? You utter twat!’

“I couldn’t do it before I went to sleep, I couldn’t do it before I went on stage, and I’d get cramp, and coke has that dusty taste, and I didn’t want that in my nose. I never did anything stronger, though I took heroin once by mistake.”

He tells me the story of how he took heroin, which is hilarious, but off the record as it involves another singer, who gave him the drugs, then tried to get off with Paula while Geldof was indisposed. He does a very funny impression of Paula saying, “No, thank you, [insert famous name here], go to bed,” in her poshest voice to the suitor. We’re back to the old Geldof, which is something of a relief. When he is in pain, that pain fills the room.

Fifi, his oldest daughter, wrote a piece recently for the Daily Mail in which she discussed her depression. As it wasn’t in the FT, Geldof found out she’d written it only when the publicist Matthew Freud mentioned it, but, he says: “If she did write it, I’d be really happy, because I really think she has an ability with words. Also, she’s decided to champion Mind, to say, ‘Hold on, I can use this stupid surname I have and maybe get a focus on this good thing.’”

She wrote that she didn’t talk about her depression with him. “Well, it’s clear as day that all of the children were and are affected by our lives,” he says. “How do you expect it to be anything other, really? The impact when Peaches died was overwhelming. And if it has such an impact on individuals who don’t know you, imagine what the impact of these events is internally, in the family. If the kids talk to each other about it, that’s really good, because they’ve all come from the same perspective. As to talking about it with me individually, they are honest and open with me, and at any point, if they thought they needed help, then that’s available to them.

“But I can’t really speak for them because they are adult individuals, and I don’t want to drag them into anything I do. It gives them a pain in the arse. And it gives them a pain in the arse when, you know, each other drags them into it. Unfortunately, the Geldofs have played a minor part in the national soap opera for a long time.”

And there, I think he’s going to leave it. Except he’s Bob Geldof, so he can’t. He takes a breath, almost physically grabs the bit in his teeth again, and off he goes. “You know, the children were never, ever, ever given a break, particularly by the Daily Mail, who engaged in a lifelong exercise in bullying,” he says. “These tiny little girls – never once did they write anything about their courage, their strength, their beauty, their abilities. If they went to a teenage party, then they were out of control, they were exactly following in their mother’s footsteps – and look at her, guess what she was – and this would be posted on the school noticeboards… When I tried to occasionally stop it, inevitably it would be a freedom of the press issue.

“Whatever people think about us, this is a normal family. Close the door and it’s normal. They’re your kids, you’re their parents. It’s still homework, it’s still tea time, it’s still that, you know? And it’s having to go to school in the morning. But it’s having to go to school where, on more than several occasions, there were 40 photographers walking backwards in front of you. There are circumstances in my children’s lives that were egregious, obviously. Imagine that: that’s the tip of an iceberg, because there’s the public thing, too. But they shouldn’t have had to live that part of it, for they were children. My kids are admirable people.

“Everyone’s affected, everyone has their own memories and their own narrative, and everybody has always tried to do the best they could. One of us didn’t make it… And it was very difficult.”

The Boomtown Rats tour starts tonight. A new hits compilation, So Modern: The Boomtown Rats Collection, is out now.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion