IRVINE — When Fran Sdao, the chair of the Orange County Democratic Party, first heard congressional candidate Gil Cisneros giving a speech last year, she went up to him after to ask, “Are you sure you want to be doing this?”

It was a fair question: Cisneros, a former Navy officer, had never run for office before. “He seemed a little uncomfortable — it didn’t come naturally to him,” Sdao said. And, after winning $266 million in the lottery, it wasn’t as if he needed a new job.

Now, as the battle for Congress hinges on vulnerable Republican-held seats across California, Democrats are banking their hopes for a blue wave on a long slate of political newcomers like Cisneros.

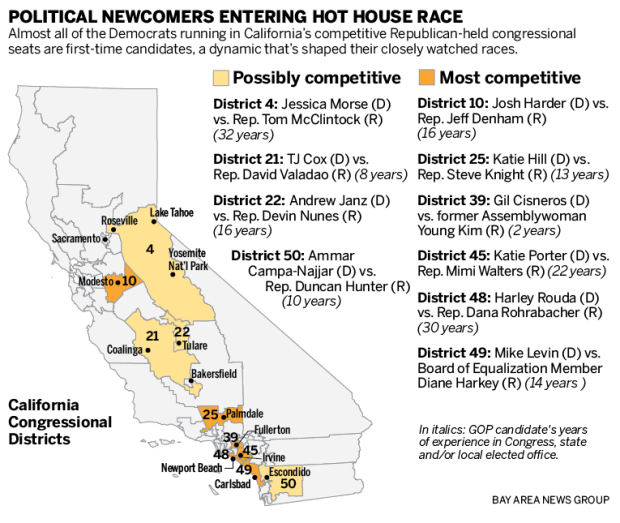

None of the Democrats running in the Golden State’s 10 most competitive GOP-held districts has ever served in elected public office — and all but one are appearing on a ballot for the very first time. They’re running against far more seasoned Republicans, both incumbents and, in two open-seat races, current and former elected officials.

This contrast has shaped races up and down the state, letting relatively unknown Democratic candidates claim the mantle of political outsiders as Republicans try to define them in voters’ minds with scathing attack ads. And the outcomes in these districts, from the nut and citrus orchards of the Central Valley to the increasingly diverse suburbs of Orange County, could decide which party controls the House.

This contrast has shaped races up and down the state, letting relatively unknown Democratic candidates claim the mantle of political outsiders as Republicans try to define them in voters’ minds with scathing attack ads. And the outcomes in these districts, from the nut and citrus orchards of the Central Valley to the increasingly diverse suburbs of Orange County, could decide which party controls the House.

“This year will be a real test of the appeal of new candidates,” said Jack Pitney, a political science professor at Claremont McKenna College and a former Republican strategist, who said it’s unusual to see so many green candidates on the ballot in the most crucial races.

More first-time candidates are taking the plunge around the country this year, but California stands out. According to a Bay Area News Group analysis, 25 of the Democratic nominees in the most competitive 61 GOP-held House seats outside of California are first-timers, compared with nine of the 10 Democrats in the Golden State’s marquee races. (Central Valley candidate TJ Cox previously ran for Congress and lost in 2006.)

Most of the political newbies, who include a former national security aide who worked in Iraq, a law professor who studied under Sen. Elizabeth Warren, and a venture capital investor who helped fund Blue Apron, cite President Trump’s victory as the wake-up call that inspired them to run.

“I had never aspired to be a politician,” Cisneros said after a campaign event in a volunteer’s backyard last month. But while he’s less polished on the stump than his GOP opponent, former Assemblywoman Young Kim, “it’s not like I’m just walking in off the street,” he argued, citing his military service, philanthropy work and role on an Obama administration arts commission.

Many of California’s in-play districts have been Republican turf for years, so there wasn’t a large bench of Democratic officials waiting in the wings to run for Congress. In addition, new rules passed in 2012 easing limits on how long legislators can stay in their job reduced the incentive for some members of the Assembly and Senate to try swapping Sacramento for D.C.

The first-time candidates all survived hard-fought primaries, in several cases defeating local elected officials and politicians who had run in the districts previously. That’s helped them grow into their roles, Sdao and other observers said.

“I think that being a bit naïve is good, because you may not fully appreciate all the challenges — you march right through them,” said Harley Rouda, a businessman and former Republican who’s running against Rep. Dana Rohrabacher in a coastal Orange County district that catches some of the best surfing waves in the country. The state Democratic Party endorsed one of his primary rivals, and he got on the ballot by the barest of margins only after a vote-counting process that stretched on for two weeks and five days.

Rouda and the other new Democrats — running at a time when voters are increasingly fed up with Washington — come without the voting records and other political baggage of their GOP opponents. As she went door-to-door in a tranquil Irvine neighborhood on a recent Saturday, walking by plug-in electric cars and front lawn cacti, law professor Katie Porter made sure to tell every constituent that her opponent, Rep. Mimi Walters, “voted 99 percent of the time with Donald Trump.”

Rouda and the other new Democrats — running at a time when voters are increasingly fed up with Washington — come without the voting records and other political baggage of their GOP opponents. As she went door-to-door in a tranquil Irvine neighborhood on a recent Saturday, walking by plug-in electric cars and front lawn cacti, law professor Katie Porter made sure to tell every constituent that her opponent, Rep. Mimi Walters, “voted 99 percent of the time with Donald Trump.”

The troupe of first-time candidates also argue they’re less beholden to the state’s Democratic establishment than they would be if they had worked their way up through the party machinery or spent years in Sacramento. That’s made it easier for some of them to differentiate themselves with stances like opposing California’s recent gas tax hike, which was championed by Gov. Jerry Brown, or calling for new leadership to replace House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi.

Still, their lack of an electoral history gives Republicans a better opportunity to define them in voters’ minds than if they were experienced officials with more established name recognition.

The Congressional Leadership Fund, a PAC associated with House Speaker Paul Ryan, has spent millions of dollars bashing them with attack ads, labeling Los Angeles County Democrat Katie Hill “immature,” painting the Central Valley’s Josh Harder as a “Bay Area liberal,” and, most damagingly, shining light on sexual harassment allegations against Cisneros. (The woman who accused Cisneros of harassment has since recanted, calling her accusation a “huge misunderstanding.”)

The PAC “went on air early to define first-time California candidates and put them on defense,” said Courtney Alexander, a spokeswoman for the group. “We have been able to set the terms of each race, and Democratic candidates have been forced to spend their money early in order to respond to our ads.”

Several of the new candidates have also been bruised by gaffes that more experienced campaigners might have avoided — like when Harder was caught on video agreeing to support taxpayer-funded abortion through the “full nine terms.” He later said he misunderstood the question and supports current law allowing women to get an abortion up to 24 weeks of pregnancy.

Moreover, polls have found that in the Trump era, Golden State voters do value elected experience. Sixty-two percent of likely voters in a Public Policy Institute of California survey in February preferred a statewide candidate to have previously served in elected office, while just 31 percent said it was more important to have experience running a business.

But so far, the political novices are holding their own. They’ve outraised their Republican opponents in almost every district, some raking in record-breaking sums or spending millions on their own campaigns. And recent polls have shown tied races or Democrats ahead in a half-dozen districts.

They’re also rejecting some traditional norms of how to run for office. Porter, for example, makes a point of bringing her three kids to campaign events. When she goes door-to-door canvassing, her 12-year-old son Luke helps enter voters’ information into the campaign app, while her 6-year-old daughter Betsy runs ahead to knock on the next door.

For female candidates, “there’s historically been a school of thought that you should never mention your children and they should never be seen on the campaign trail, or it invites questions about how you’re balancing work and family,” Porter said. “I think it’s best to show people how you’re doing it… and my kids have enjoyed it way more than I expected.”

At a crowded office opening party for Hill — whose district includes Ronald Reagan’s grave — volunteers argued that the 30-year-old nonprofit executive didn’t need elected experience. Judy Mayer, a Simi Valley retiree, said Hill’s personal experiences, like dealing with hundreds of thousands of dollars in medical debt and an unplanned pregnancy, were more important. “She’s not a typical politician,” Mayer said.

All of the first-time candidates are learning just how unpredictable the campaign trail can be. On a recent Saturday afternoon, Democrat Mike Levin set off up Highway 1 to knock on voters’ doors in his Orange and San Diego County district, with a volunteer driving and a reporter in the backseat. But the group was stymied when they got to the locked entrance of the exclusive Niguel Shores gated community.

When another car pulled up, Levin and company swerved to tailgate in behind it. It didn’t work: The access bar fell down, smacking the top of their car, and spikes shot up from the entranceway, slicing through the vehicle’s back tires.

“Oh my God,” Levin exclaimed.

The car slid to a halt on a manicured block looking out over the Pacific — just across the street from a house with a bright blue Mike Levin yard sign out front. Its owners, Hal and Mary Schaffer, were delighted to see the candidate knocking at their gate, and helped him and his team arrange a tow.

“Anything can happen in a campaign,” Levin said later, as he hustled to his next event. “That’s what makes it interesting.”