Colombia adoptees find family decades after volcano tragedy

BOGOTA, Colombia (AP) — Jenifer de la Rosa was just a week old when Colombia’s Nevado del Ruiz volcano exploded, unleashing a wall of mud that buried an entire town and left 25,000 dead.

In the chaotic aftermath of the 1985 disaster the infant was handed over to a Red Cross worker and eventually adopted by a Spanish couple.

Now a documentary filmmaker, she’s been on a quest to answer one question that has haunted her: What happened to her biological family?

On Thursday, a genetic institute in Colombia’s capital announced it has solved part of the puzzle, with scientists revealing they have confirmed through DNA testing that a woman still living in the South American nation is her sister.

“I thought this can’t be true,” de la Rosa said. “This could only happen in a movie.”

The story of the lost sisters could be one of many involving children who were separated from their parents after the Nevado del Ruiz erupted, rescued from the rubble and later put up for adoption after no relative arrived to claim them.

According to local media, children who weren’t reunited with their families within six months were considered abandoned, even though it’s possible some of their parents were still recovering in hospitals and not able to search for them.

An outpouring of Colombians and foreigners eager to adopt were granted permission, raising the children as far away as Holland and France. Now as they build lives as adults, some like de la Rosa are coming back, searching for closure.

“It has been a thousand different emotions,” de la Rosa said. “I’ve always kept questioning.”

The journey of the adoptees often leads first to Francisco González, who himself lost his father and brother in the tragedy and made it his mission to reunite families. He said his foundation, Armando Armero, has gathered information from 478 people looking for children they are convinced survived as well as 65 kids who were adopted.

“We know many children came out alive,” he said from his home, where he keeps old newspapers and a stack of binders filled with case information. “They were put up for legal adoptions and informal ones and there was no efficient state presence.”

The events that November day were in many ways a tragedy foretold.

Armero was known as the “white city” for its abundant cotton crops. Residents didn’t fret much about the nearby volcano, nicknaming it the “sleeping lion.” Scientists warned of a deadly eruption for months, but no response plan was put in place.

When the Nevado del Ruiz erupted, it melted part of its snowcap, creating a 150-foot-high wall of mud that swept down the Lagunilla River.

About 23,000 of Armero’s estimated 28,000 residents died or went missing as the mudslide pulled trees from their roots and enveloped entire homes. Another 2,000 people were killed or disappeared on the opposite side of the volcano.

It was the image of a child – 13-year-old Omayra Sánchez – holding onto life as rescuers tried to free her body from the mud that became emblematic of the tragedy and captured the world’s attention in the days after the tragedy.

With families scattered and few in possession of IDs, relatives embarked on their own individual quests to locate their loved one. González himself went searching for his father and brother but to this day has never found their remains.

Images of rescued children were published in newspapers in hopes a relative would find them. Some were too young to even say their name.

“Approximately eight months,” one notice states alongside the picture of a dark-hard boy with squinting eyes. “He says ‘Pa’ and ‘More.’”

While many of their parents did likely die, others were badly injured but alive.

Gladys Primo was in a coma for three months before she woke up to discover that her young daughter and son were nowhere to be found. To this day, she still believes they are alive, convinced that a young boy shown on television being lifted into a helicopter is her son.

She’s among the hundreds who have submitted DNA for testing.

“I know one day they are going to appear,” she said.

Primo and other families say Colombia’s child welfare agency has left them in the dark, never providing a full accounting of which kids were adopted. The government office in charge of adoptions did not respond to a request for comment.

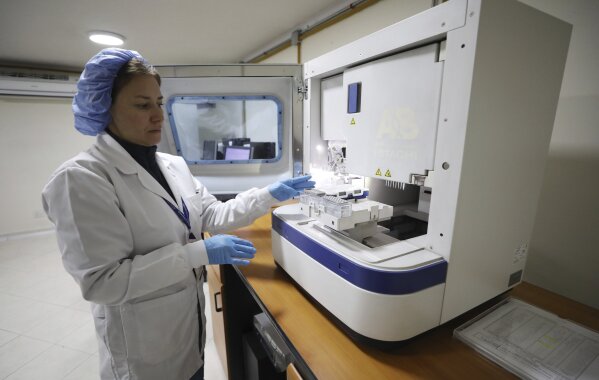

Seven years ago, González approached Emilio Yunis, a Colombian pioneer in genetic studies, to see if he could help find relatives. That work is now continued by his son, Juan Yunis, whose genetic institute has collected profiles from 275 people linked to the Armero tragedy, including 48 men and women adopted as children.

Juan Yunis said they have helped solve four cases, including one man who grew up in the U.S. and was reunited with his biological father. He said the state could do more by providing labs like his with access to the DNA of those buried in mass graves.

“They’ve done absolutely nothing,” he said.

De la Rosa, 34, for her part, has always known that she was adopted after the tragedy. Her Spanish parents openly shared what they knew about her story, including papers indicating her biological mother’s name is Dorian Tapazco Tellez.

During her teen years, she began searching on the internet for her birth mother’s name but never came up with any results.

The itch to find out more came and went, culminating with her decision to pursue a career in journalism, an avenue that de la Rosa says allowed her to explore a painful, confusing part of her past but from a distance. She studied filmmaking and is now at work on a documentary titled “Daughter of the Volcano.”

“I decided I had to come to Colombia,” she said. “It was a part of me.”

When she began searching in earnest, she was stunned to find a woman working as a street food vendor in Barrancabermeja also searching for a mother with a similar name. Ángela Rendón, 35, has lived a dramatically different life as the single mother of two teenage girls but also spent a lifetime wondering if she had living relatives.

With González’s help, they met for the first time last year, though at that point they did not have DNA confirmation that they were family.

De la Rosa was skeptical, though Rendón held out hope they’d be a match.

“Only God and science know,” she told her.

What little they know of their story coincides: Documents and anecdotes both have uncovered indicate that their mother left them with different people in the tragedy’s aftermath, indicating she survived. Both are now on a mission to find her, but they have not been able to find anyone with her name in the nation’s civil registry.

The tests disclosed Thursday establish a maternal link, though scientists are not able to determine if they share a father without more genetic material.

De la Rosa said she still struggles to think of the two as sisters, but Rendón sees surprising similarities, like how they both showed up to their initial meeting in flower-print jackets and years before had gotten tattoos on their left arm.

As they spoke to journalists Thursday, de la Rosa rubbed her sibling’s shoulder and they shared a brief hug. Rather than an instant bond, the women said theirs is a relationship they will continue to foster through the years.

“We’ve lived very, very different realities,” de la Rosa said. “We’re an example that ties are built.”