Electric and hybrid 4×4 vehicles explained

© JLR Global

© JLR Global Barely a day goes by without another headline announcing the demise of the internal combustion engine.

While many of those predictions are misleading or simply wrong, there is a definite shift towards hybrid and electric vehicles.

The capability of these machines is increasing, while their prices are coming down. So could it be time to make the switch?

See also: Diesel-electric Peugeot 508 on test

Hybrids can be broadly separated into three categories

- Mild hybrids, which harvest energy under braking to assist the combustion engine, but generally have little or no ability to actually propel the car on electricity alone.

- Full hybrids that work on a similar principle, but provide a greater degree of assistance, plus a limited electric-only capability (usually only for a few miles at a time).

- Plug-in hybrids where the battery can be charged from an external socket, allowing far greater amounts of energy to be stored.

As a rule of thumb, the benefits of running a hybrid come down to how often the electric motor can be used in place of the combustion engine.

- Electricity is around a third of the price of petrol or diesel when purchased from a charging point (and whatever you harvest under regenerative braking is free, of course), but there are a few points to watch.

- Plug-in hybrids work best when a substantial portion of the journey can be completed on electricity alone.

- If they’re not plugged in on a regular basis – or if the mileage is simply too high – then the fuel economy figures will end up tumbling.

- Likewise, a heavy right foot will cause the combustion engine to intervene more frequently.

- One plug-in 4×4 we tested returned just 21mpg on a spirited drive through the Cotswolds, despite being officially rated at more than 100mpg. However, under the right conditions, the same car was good for around 15 miles of real-world electric-only driving.

- That means that short trips, such as the school run or back and forth across the farm, could potentially be carried out very cheaply indeed.

There are other practical benefits too.

The seamless high-torque delivery of an electric motor is ideally suited to off-roading (incidentally, wading depths of hybrid cars are generally unchanged from their petrol or diesel equivalents).

Likewise, there’s anecdotal evidence to suggest that they reduce the wear of components such as brake pads.

It’s worth emphasising that these cars all use slightly different configurations. The Volvo XC90 T8, for instance, uses a standalone e-axle on the rear.

The RX450hL and the Outlander both use a broadly similar setup with a motor on each end, while the Range Rover P400e uses a single motor mounted inside the gearbox.

Financial incentives

The other pros and cons are largely financial, with the principle drawbacks being purchase price and depreciation. Hybrid vehicles can cost up to 20% more than comparable petrol or diesel models.

Generally, the price goes up with the size of the battery, although this can be offset by downsizing the combustion engine (as Land Rover has proved with the 2-litre plug-in hybrid versions of the Range Rover and Range Rover Sport).

While the government effectively scrapped the plug-in car grant recently, the taxation system is still largely based on carbon dioxide emissions.

The new road tax system means that hybrid cars registered after 1 April 2017 will pay the same standard rate as petrols and diesels, but the first-year rates remain preferential.

For instance, the vehicle excise duty on a Range Rover P400e hybrid would be £830 less in the first year than a mid-spec TDV6 diesel and £2,110 less than the top-spec petrol V8.

The benefit in kind (BiK) tax charged on company cars remains tied to their carbon dioxide rating too. A

s things stand currently, cars that emit less than 50g/km of carbon dioxide – such as the Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV – would be taxed at 16% of their P11D value for the 2019/20 financial year.

The remainder of plug-in hybrids would typically fall into the 51g/km to 75g/km bracket, which will be taxed at 19%. In contrast, the same Outlander, fitted with Mitsubishi’s relatively low-carbon dioxide (139g/km) diesel would be taxed at 35%.

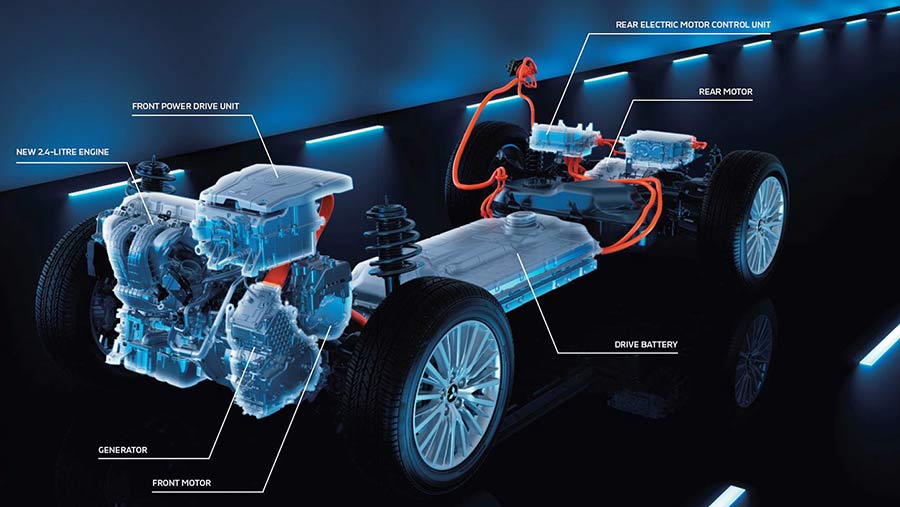

The Outlander PHEV skeletal system layout

A similar incentive applies to national insurance contributions paid by employers on company cars.

What’s more, companies can write down a higher percentage of the purchase cost of vehicles that emit less carbon dioxide, with cars rated at less than 50g/km of carbon dioxide eligible for a 100% capital allowance.

There are also grants available for installing charging points and the potential to set your own tariff if these are open to the public (for instance, if there’s a farm shop or a B&B on site).

If you’re considering a hybrid vehicle, it’s advisable to do some research on real-world fuel economy figures (bearing in mind that these could be substantially different to the manufacturer’s claims) and then speak to an accountant to gauge what could be done to offset any price premium.

Ultimately, it’s hard to state definitively whether or not the figures will add up in all cases. However, what we can say is that the incentives are significant and definitely worth investigating.

On test: Lexus RX450hL

Silence. That’s the first thing that strikes you as you pull away in the Lexus RX450hL. Even at cruising speeds there’s little more than the slightest hint of wind and road noise.

Being a Lexus, it’s beautifully finished inside, everything moves around at the touch of a button and the gadget count in the cabin is sky high.

Squeeze the throttle a little harder and the 3.5-litre petrol V6 wakes up with a gentle purr. It’s connected to the front wheels via a continuously variable transmission, which is shared with a 165bhp electric motor.

There’s also a 68bhp electric motor that’s used to drive the rear wheels, plus a smaller motor-generator unit, which replaces the traditional starter motor and alternator.

Combined, the total output comes to 308bhp, giving sprightly performance for a car that carries seven people and stands some 5m long.

This is a so-called full hybrid, with a 2kWh lithium-ion battery pack stashed under the rear seats. Without a plug-in option, we struggled to generate enough energy to engage electric-only mode, but the motors did allow the engine to shut down frequently for short periods.

The end result was around 30mpg driving on rural A- and B-roads – not transformative, but more than you might get in the real-world from a vehicle of this size with a conventional petrol engine.

On the road, the long-wheelbase RX450hL doesn’t offer the last word in agility, but it does feel safe and secure, while the four-wheel drive and raised ground clearance should provide a modicum of off-road ability.

Back on tarmac, it wafts along with a supple easy-going ride that only adds to the general feeling of tranquillity inside the cabin.