Whether they want it or not, the last year has given Americans a master class in political polarization.

But the terminology commonly used to describe the peeling apart of the country’s Republican and Democratic factions — “red states and blue states,” “coastal elitists vs. flyover country” and the like — tends to overlook the far more local widening fissures within the states themselves, between diverse and well-educated urban counties and their less populated surroundings.

The political power of one of those populous counties was vividly displayed in Virginia’s gubernatorial election on Tuesday, which saw Democrat Ralph Northam thumping Republican Ed Gillespie by an unexpectedly robust nine-point margin. While Gillespie largely matched Donald Trump’s 2016 shares in the state’s rural south and west, Northam’s margins in dense and affluent suburban counties exceeded even Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton’s successes there in the last two presidential cycles.

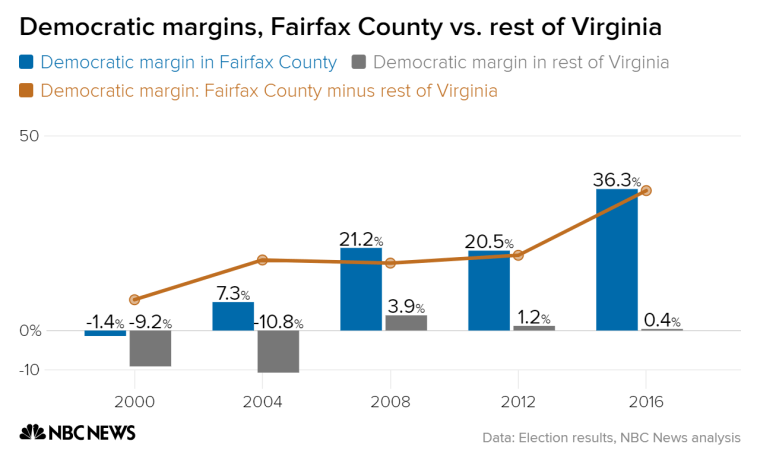

In fact, in Fairfax — the largest of those wealthy Virginia counties — Democrats have increased their presidential election advantage from a narrow loss in 2000 to a 36 point win in 2016. (Northam won the county by 37 points.) But, despite Virginia’s increasing embrace of Democrats in recent years, in the same period of time the Democratic share of the vote in the remainder of the state has increased just from a nine point deficit in 2000 to nearly an even tie with the GOP now.

At first glance, Virginia, with its rapid suburban population growth and deepening blue tint, may seem like the exception rather than the rule. But the pattern is one that’s been replicated across the country.

An NBC News analysis of voting and demographic trends in each of the lower 48 states shows that, since 2000, Democrats have improved upon their presidential election margins in the lion’s share of the most vote-rich and populous counties in America even as their share of the vote in the remainder of each state was stagnant, decreased or — at best — grew at a far slower pace.

The data seem to show two important trends since 2000.

One, Barack Obama’s candidacy and presidency blew open the partisan voting divide between the most urban counties in states and the rest of their population. The 2008 election seemed to be a watershed in the split.

Two, the changes that followed 2008 were not just about the minority vote in urban centers. In 2016, without the first black president on the top of the ticket, the gaps between these counties and the rest of the states widened more.

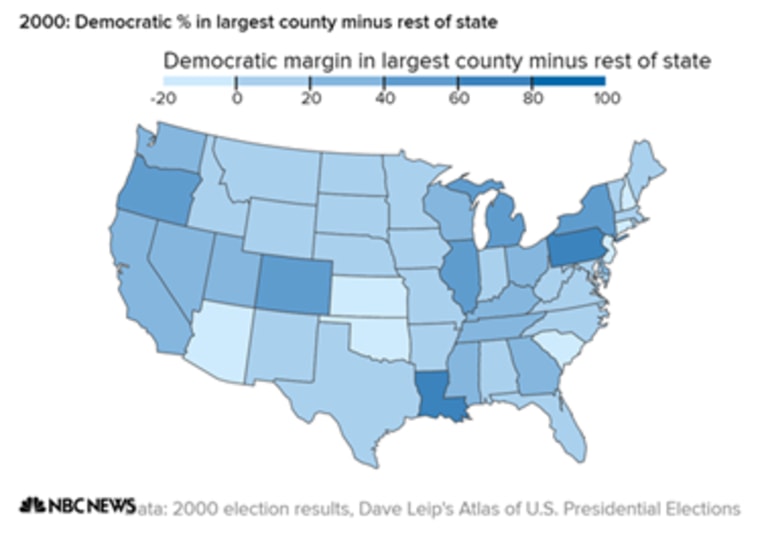

In 39 of the lower 48 states, Democrats significantly increased their vote share in presidential elections from 2000 to 2016 in each state’s most populous county. And in all but two of those states, Democratic margins outside of the most populous county failed to increase at similar rates, widening the partisan gap between each state’s more urban center and its surroundings.

Viewed as a whole, the numbers suggest a common urban political culture is rising out of the country’s big cities that overrides the nation’s regional differences so that the political identity of Atlanta has more in common with Milwaukee or Denver or even Miami than it does with the rest of Georgia.

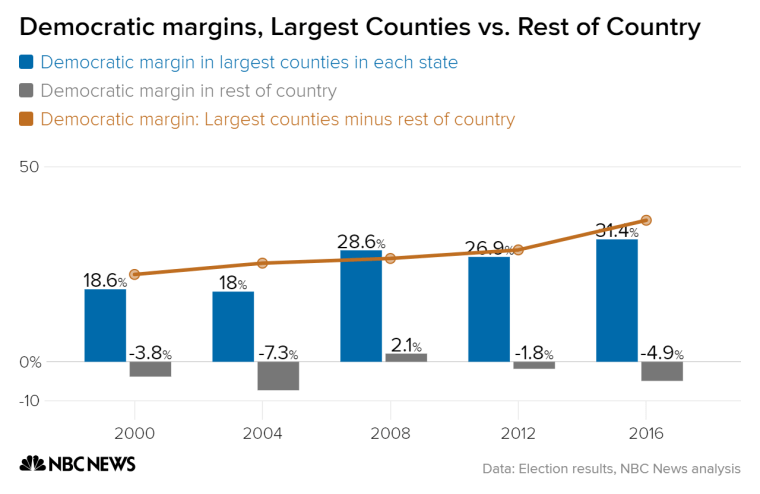

Combining the votes from 2000-2016 in all of the contiguous United States shows how the Democratic share of the vote in each state’s largest county rose from a cumulative 18.6 percent in 2000 to 31.4 percent in the last election. Subtracting those votes from the total shows that, on average, Democrats only won the remainder of U.S. counties once in the past four presidential elections — in Barack Obama’s 2008 landslide.

In fact, in half of the mainland U.S. states between 2000 and 2016 — in places as politically divergent as Alabama, Kansas, Indiana, Maine and Wisconsin — Democrats saw both a significant increase in their margins in each state’s most populous county and a significant decrease in the party’s performance in the remainder of the state.

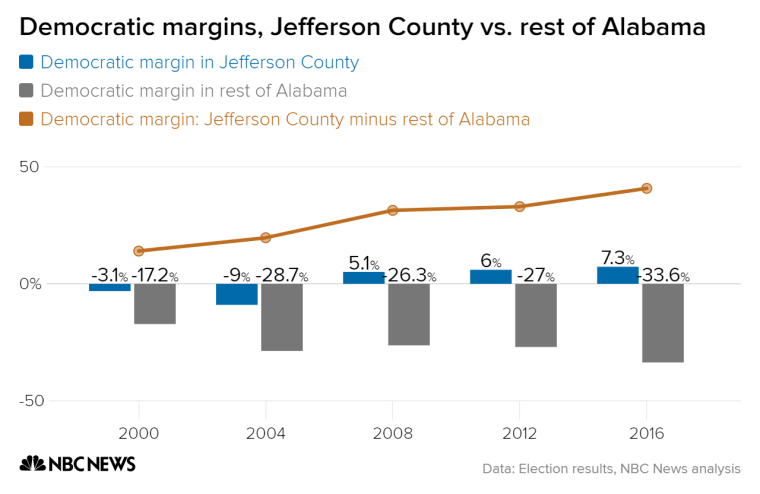

Take, for example, Birmingham’s Jefferson County, Ala., home to banking and medical centers, a thriving arts community and the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

As recently as 2000, Birmingham still favored Republicans in presidential elections. But since the election of Barack Obama, Jefferson County has seen increasing margins for Democratic White House candidates, even as the remainder of the state has become significantly more conservative.

The changing landscape in Alabama provides a vivid example of how self-sorting — particularly by education and race — is widening existing divides between urban centers and rural outskirts.

In 2000, 24.6 percent of Jefferson County’s 25 and older population had a college degree, while the college-educated population of the remainder of the state stood at 18 percent. Sixteen years later, that 6.5 point gap has edged close to double digits, with 33 percent of Jefferson County adults holding a bachelor’s degree or more, while 23.4 percent of the remainder of the state does.

Jefferson County has become more diverse faster than the remainder of the state as well. Its white non-Hispanic population fell from 57.4 percent in 2000 to 50.1 in 2016, while the remainder of the state’s share dropped more modestly from 72.6 percent to 68.2 percent.

Race is also one of the driving factors in the particularly dramatic polarization in other Southern state: Tennessee. While Nashville’s Shelby County has long been a reliable source of Democratic votes, the last 16 years have seen a double-digit increase in Democratic margins there even as their share in the rest of the state steadily sunk.

The phenomenon is not unique to the American Deep South, where Democratic and Republican labels have been particularly fluid since the Civil Rights movement.

Similar trendlines appear in many states with dense urban centers and far-flung rural areas, from Minnesota (where the gap between Democratic margins in Hennepin County and the rest of the state has widened by 28 points since 2000) to Oklahoma (where the gap has grown by 37 points.)

Not all of these densifying and diversifying large counties are destined to reshape their home state’s politics in favor of Democrats. Despite the jump in Democratic margins in urban centers in Alabama and Tennessee, for example, both states have become steadily more — not less — red in the last five presidential elections.

But as the Virginia race demonstrated last week, the fact that these diverse, affluent and well-educated population centers have become significantly more blue in recent years should give Republicans pause in states where a spike in Democratic enthusiasm can easily swing an election.

And these yawning gaps between urban and rural regions illustrates how political partisanship extends far beyond the contrast between the coasts and Middle America — to clashes of culture and politics well within the borders of the states we call home.