Is Combatting Sexual Abuse Becoming a Partisan Issue?

Defenders of Alabama’s Roy Moore are politicizing a problem that crosses party lines.

For a moment there, it looked as though the public conversation about sexual harassment and assault might escape political polarization by virtue of the plague’s depressing ubiquity. Fox News founder Roger Ailes was a pig, but so, it turned out, is Hollywood producer and Democratic donor Harvey Weinstein. There was little to gain by quibbling over whether Fox News’ Bill O’Reilly or Eric Bolling is pervier than NPR’s Mike Oreskes or ABC’s Mark Halperin. And lest conservatives felt the urge to wax pious about the parade of Hollywood bad boys (James Toback, Brett Ratner, Louis C.K., Andy Dick, Kevin Spacey…), above the entire mess hovered the specter of President Donald Trump.

Not that the big-p political realm escaped scrutiny. Stories continue to bubble up about frat-boy behavior not just on Capitol Hill but also in state houses across the country. “It’s even worse in state legislatures. They are notorious places people get harassed,” said pollster Anna Greenberg. “State capitals are often kind of isolated. State legislators travel there, stay there alone.” Left to their own devices, lawmakers get a little crazy.

But tellingly, the focus has been not so much on punishing specific bad actors from either team as on reforming what are widely recognized as deeply toxic cultures. After years (decades, really) of foot-dragging, both chambers of Congress moved in the past week to mandate anti-harassment training for members and staff. (Much more needs to be done, but it’s a start.) Republican, Democratic, Independent—everyone lives in a glass house. Thus, while the occasional political stone was tossed, the outcry over men behaving badly was largely unburdened by left-right tribal baggage.

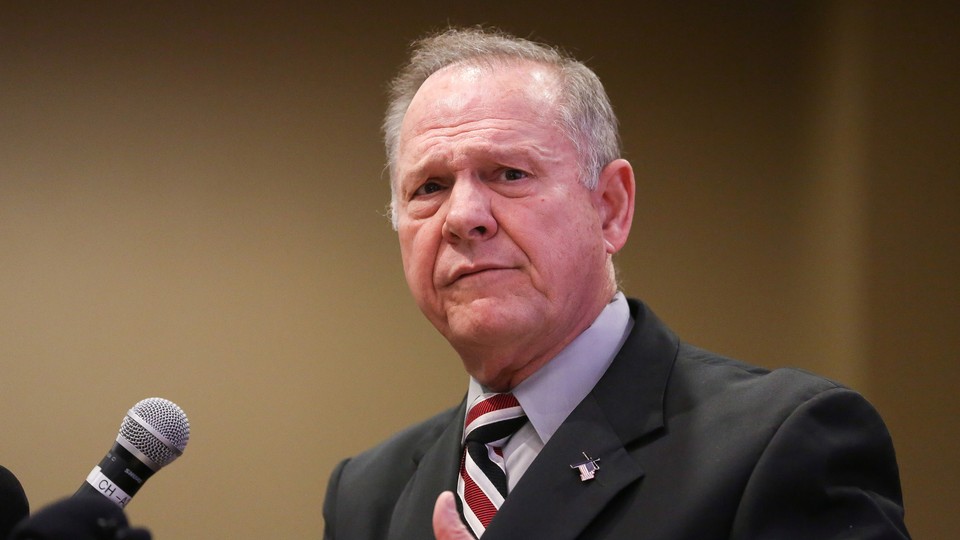

Then came the predation accusations against Republican Alabama Senate candidate Roy Moore, and just like that, the issue was jerked back into more familiar, more partisan territory. Two women have accused Moore of sexual abuse, three others have said he pursued them when they were teenagers and Moore was in his 30s. Tribal lines were drawn, the wagons were circled, and familiar positions were staked out. Moore’s fan base (heavy on religious conservatives) blamed the liberal media, Democratic haters, the Republican establishment, and, of course, those lying women—all of whom Team Moore set out to discredit. In Washington, Republicans on both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue issued tortured statements about how Moore needed to leave the race “if” the charges proved to be true. Fox News generally tiptoed around the erupting scandal, while Sean Hannity in particular treated Moore with such gentleness that his advertisers began to balk. Donald Trump remains uncharacteristically quiet even now.

All of which stands to benefit Democrats in any number of ways. Most narrowly, Moore could stay in the race but prove so toxic that Alabama’s typically blood-red Senate seat goes blue. Or, Republican leaders’ efforts to recruit a write-in candidate could wind up splitting the vote, not to mention widening the existing rift between party leaders and some in their base. Or, Moore could emerge victorious, saving the seat for his party but damaging the GOP brand for years to come. “What do we do with him if he becomes the face of the Republican Party?” lamented GOP strategist Katie Packer Beeson, whose focus is improving her team’s standing among women.

Regardless of what happens in Alabama, Moore has the potential to drive gals to the polls nationwide to register their displeasure with his party—this year’s version of Todd “legitimate rape” Akin. As Beeson noted, Trump’s sexist image has already galvanized many women against the GOP; having Moore ascend to the Senate would be like pouring kerosene on a campfire: “The Democrats could basically run on, ‘Look at what the other party has become: the party that protects sexual harassers and child molesters!’”

Here’s hoping it does not come to that. Whatever your political leanings, the polarization of sexual harassment and abuse is not a positive development. As has been driven home so graphically of late, this is a widespread, crosses-pretty-much-every-demographic-line problem. To make meaningful progress addressing it, no political or ideological cohort can be in a defensive crouch. Everyone has to face distasteful realities “and call out bad actors on both sides,” said Beeson. As Caitlin Flanagan so eloquently noted, this means acknowledging that Donald Trump and Bill Clinton have abhorrent track records with the ladies.

Ironically, the particular ickiness of the Moore allegations may prevent this situation from sinking into the swamp of tribalism. As Beeson put it, “This isn’t about disrespecting women in the workplace. This guy clearly had a strong attraction to young girls.” Even in this society’s not-so-nuanced culture wars, plenty of people draw a distinction between an alleged sexual harasser and an alleged child predator.

As additional evidence surfaces to support Moore’s accusers, more and more Republican leaders are abandoning him. Senators Mike Lee and Steve Daines were among the first to rescind their support, but the trend is gaining speed. On Monday, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell called on Moore to leave the race, followed on Tuesday by Speaker Paul Ryan. Also on Tuesday, the RNC ended its fundraising agreement with Moore’s campaign, as the National Republican Senatorial Committee did last Friday. Down in Alabama, meanwhile, the state party’s steering committee will meet later this week to discuss whether or not to cut Moore loose.

At this rate, the candidate soon will be left with only with his most blinkered loyalists. Tuesday night, even Sean Hannity said that Moore needed to “come up with a satisfactory explanation” for his “inconsistencies” within 24 hours or exit the race.

This is, obviously, as it should be. Whatever spotlight politics brings to an issue like this, it also ups the risk of backlash, divides people who might otherwise have been allies, and increases the likelihood that the vulnerable individuals involved will become collateral damage in the broader partisan war. In many ways it’s easier to tackle something like this when it stays out of the political realm, said Greenberg, “when regular people see this as something they have the power to do something about.” She added, “It gets harder once Steven Bannon is involved.”