Trump’s trade war: the one thing he does know is that doing nothing is not the answer

As Donald Trump tries to do something – anything – to curtail the mass transfer of technology to China, we look at tariffs in the context of US efforts to rein in abuse of intellectual property rights, in the conclusion to a two-part exploration of the trade war

The summer of 2017 marked six months of almost constant turmoil in the presidency of Donald Trump. On July 1, an editorial headline in The New York Times read, “President Trump, Melting Under Criticism. Unlike his predecessors, this president can’t seem to take the heat.”

Two days later, Times columnist and Nobel Prize winner Paul Krugman, focusing on the United States’ trade dispute with China wrote a scathing piece headlined, “Oh! What a Lovely Trade War. Let’s do something stupid to please the base.”

How China’s blatant IP theft, long overlooked by US, sparked trade war

Another Times columnist, Charles Blow, wrote, under the headline, “The Hijacked American Presidency” that “a madman and his legislative minions are holding America hostage.” Ostensibly a piece about Trump’s nastiness to the media, Blow began, “Every now and then we are going to have to do this: Step back from the daily onslaughts of insanity emanating from Donald Trump’s parasitic presidency and remind ourselves of the obscenity of it all, registering its magnitude in its full, devastating truth […] We must remind ourselves that Trump’s very presence in the White House defiles it and the institution of the presidency.”

An on and on. It had been like this since Trump announced his candidacy for president. The obloquy only worsened once he took office. An investigation by special prosecutor Robert Mueller into possible collusion between the Trump campaign and “the Russians” had started in May. A July meeting with Vladimir Putin did nothing to dispel Democrat claims that he was the Russian leader’s boy. He hired a Wall Street loudmouth as communications director, which caused his press secretary to quit. The Wall Street loudmouth left just days later after badmouthing Chief of Staff Reince Priebus and chief strategist Steve Bannon, both of whom left soon afterwards.

Trump was feuding with Germany, Britain, the rest of Europe and Nato. He was simultaneously calling on South Korea to help pressure North Korea, with whom he was in an unprecedented war of words, to give up its nuclear arsenal while asking Seoul to renegotiate its bilateral trade agreement with the US. In a cabinet meeting about the Koreas, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said, to no one in particular, “He’s a f**king moron.” He was at odds with leaders of Canada, Mexico and Australia, and seemed indifferent to alienating just about every country in the world that he might need on the US side in the event of a trade war with China.

So when, after a failed July 2017 meeting in Washington between Chinese Vice-Premier Wang Yang, US Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross and US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, the US administration began ratcheting up the pressure on Beijing to narrow the trade gap between the two countries and find ways to stop what it believed were Chinese violations of US intellectual property (IP) rights, it was business as usual in a crazy administration.

Trump seemed to have a resolve that his predecessors lacked, yet few were willing to go on the record backing him, or even to say that he was headed in the right direction. His threat to use tariffs against China, reminiscent of Bill Clinton’s threat to do the same in 1996 over Beijing’s failure to protect US intellectual property, caused an outpouring of contempt from the US elite, just as Clinton’s threatened 100 per cent tariffs on US$2 billion of Chinese imports had.

Behind the scenes, though, according to journalist Bob Woodward’s recently released book Fear: Trump in the White House , the US president’s determination to take on Beijing on trade conflicted with his hope that Chinese President Xi Jinping would help him convince North Korea’s Kim Jong-un to denuclearise.

While preparing a speech announcing his mid-August memorandum to US Trade Representative (USTR) Robert Lighthizer, directing him to investigate China’s IP practices, Trump told Lighthizer, national economic adviser Gary Cohn and others that he specifically did not want to highlight China. He wanted to keep things general. His staff pointed out that that approach was ludicrous – the entire investigation was about China, and nobody else.

Washington will turn a blind eye no longer. Today, I am directing the United States trade representative to examine China’s policies, practices and actions [regarding US intellectual property]

On August 14 last year, Trump announced Lighthizer’s investigation.

“We’re going to be fulfilling another campaign promise by taking firm steps to ensure that we protect the intellectual property of American companies and, very importantly, of American workers,” he said. “The theft of intellectual property by foreign countries costs our nation millions of jobs and billions and billions of dollars each and every year. For too long this wealth has been drained from our country while Washington has done nothing – they have never done anything about it. But Washington will turn a blind eye no longer. Today, I am directing the United States trade representative to examine China’s policies, practices and actions [regarding US intellectual property].”

Trump spoke for about two minutes, then sat down at a small desk next to the podium. As he uncapped his pen, he looked at reporters and added, “And this is just the beginning, I want to tell you that. This is just the beginning.” Then he signed the memorandum as Lighthizer, Mnuchin, Ross and others looked on. He had mentioned China once.

For all his talk about the trade imbalance with China, the issue of technology theft was more important to the US economy and to its national security. After several decades of steady technology transfers to China, many of which had enabled the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to modernise, alarm bells, which had been ringing for years, were now clanging loudly in Washington. Aside from standard military applications, tech was being used to develop cyber and information capabilities that would be found on the battlefields of the 21st century.

Lighthizer’s investigation was a legal process carried out under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, an American law that allows the US to take action against a foreign country whose trade practices violate trade agreements or are “unjustifiable and burden or restrict” US commerce. Both George H.W. Bush’s 1992 and Clinton’s 1994 tariff threats accompanied Section 301 investigations into China’s IP practices.

Barack Obama’s administration launched a 301 investigation in 2010, related to Chinese policies affecting trade and investment in green technologies. The law requires the US to try to negotiate a settlement with the country in question and to file any complaint to which a 301 investigation might lead with the World Trade Organisation.

Four days after Trump’s directive, Lighthizer requested consultations with Beijing. China’s Minister of Commerce Zhong Shan replied 10 days later, opposing the investigation altogether. He had little choice. As Lighthizer’s report later detailed, since 2010, Beijing had committed on at least 10 separate occasions – including during visits to the US by Xi himself – not to use technology transfer as a condition for market access to China and not to press for the disclosure of US companies’ trade secrets in regulatory or administrative proceedings.

Lighthizer’s announcement of the investigation called for written comments from interested parties by September 28, followed by a public hearing in Washington on October 10, after which those who testified could submit rebuttal comments by October 20. Seventy-four letters were received from “interested parties” in the US and China, and 14 witnesses testified at the hearings.

Forced transfer of IP is a near ubiquitous phenomenon experienced by American companies seeking to sell products in China

The Americans who testified on October 10 told stories of IP theft that – as the first witness, Richard Ellings, head of the US Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property (IP Commission), noted – totalled US$1.6 trillion over the past four years. Ellings quoted a former head of the National Security Agency, Keith Alexander, who called cyber espionage “the greatest transfer of wealth in history”.

Testimony from Chinese who spoke that day painted a different picture. Jin Haijun, a professor at Beijing’s Renmin University testifying on behalf of the China Intellectual Property Law Society, told the panel, “We cannot forget China didn’t have any IP laws or regulations around 40 years ago […] It is probably fair to say that no other country in the world has paid more attention to the build-up and the strengthening of IP protection than China in such a short period of time.”

Chen Xu, chairman of the China General Chamber of Commerce, said the chamber believed that Trump’s investigation was “misguided in many ways”, and that “the allegation that Chinese companies are directed by the Chinese government with a purpose of acquiring or stealing intellectual property from them is unfounded.”

Denials that a problem even existed were not hopeful signs for a timely resolution.

Made in China 2025 was a wake-up call when first mentioned by Premier Li Keqiang in 2015. China’s plan would focus on 10 key sectors “to transform China from a manufacturing giant into a world manufacturing power.” Most involve advanced technology.

As US leaders see it, Beijing aims to supplant the US as the world’s tech leader and manufacture all that tech itself. Bloomberg News noted in September that Beijing has set market-share targets for Chinese companies that “would virtually lock foreign companies out of many industrial segments in China and threaten market disruption for businesses across the globe”.

All governments help their industries. The US spends billions of dollars on scientific research annually, much of which has helped make Silicon Valley what it is today. The internet was a US Department of Defense creation. Japan’s rapid post-war growth was led by industrial policy set in Tokyo. Germany adopted an Industry 4.0 Plan in 2013, from which, Bloomberg notes, Beijing drew heavily in crafting Made in China 2025.

But China’s acquisition spree of advanced Western technology over the past few years had been unparalleled. Even before Trump, Obama and leaders in the EU had begun to put the kibosh on Chinese acquisitions of firms with proprietary advanced technology.

Voices who said it was insane to allow a large chunk of American manufacturing, including much of its technology hardware, to go to a country many considered a strategic adversary, were beginning to be heard. The political ideologies of the two countries were diametrically opposed. In colloquial terms, there was no way Washington was going to let Beijing rule the world. But many roads seemed to be leading in that direction, and Made in China 2025 was sure to accelerate the trip.

As Lighthizer’s 301 investigation proceeded, leaders in Beijing were working furiously behind the scenes to deal with the sideways turn their relationships with American leaders had taken. “Who is Trump? What does he want?” These were questions many had been asking about him and his trade views since his election. Now, they were asking with a new urgency.

Various members of the US elite, whom Vice-President Wang Qishan dubbed “old friends”, began passing through Beijing with insight, advice, comfort food. Henry Kissinger, Henry Paulson, Lawrence Summers and others stopped by for chats, at times receiving positive coverage from the press for trying to save the world from Trump’s tariffs. They were a logical, if incongruous, source of information.

China’s leaders, who grew up and thrived under a system where the elite dominated, wanted to know if Trump was an anomaly who could be waited out until things returned to normal. Philosophically in agreement with them, the US media was conspicuously silent about the propriety of Americans seemingly advising Beijing on how to counter US economic policy.

The Wall Street Journal reported that Wang Qishan had told his American counterparts that he was always available to meet “informally” – that if they removed their neckties, that made the meeting “unofficial” and he could see them as an “old friend”. It reflected how things worked in China. But “remove your tie” would be an initiation into a little conspiracy with a member of China’s senior leadership. Why would an American do that? The press did not seem curious.

The people with whom Chinese officials are familiar in Washington are mainly the enemies of Trump. Trump hates those people

It did not matter. As Shi Yinhong, a professor of international relations at Renmin University, would later say, “The people with whom Chinese officials are familiar in Washington are mainly the enemies of Trump. Trump hates those people.”

Wang’s “old friends” had made the problem Trump was trying to fix.

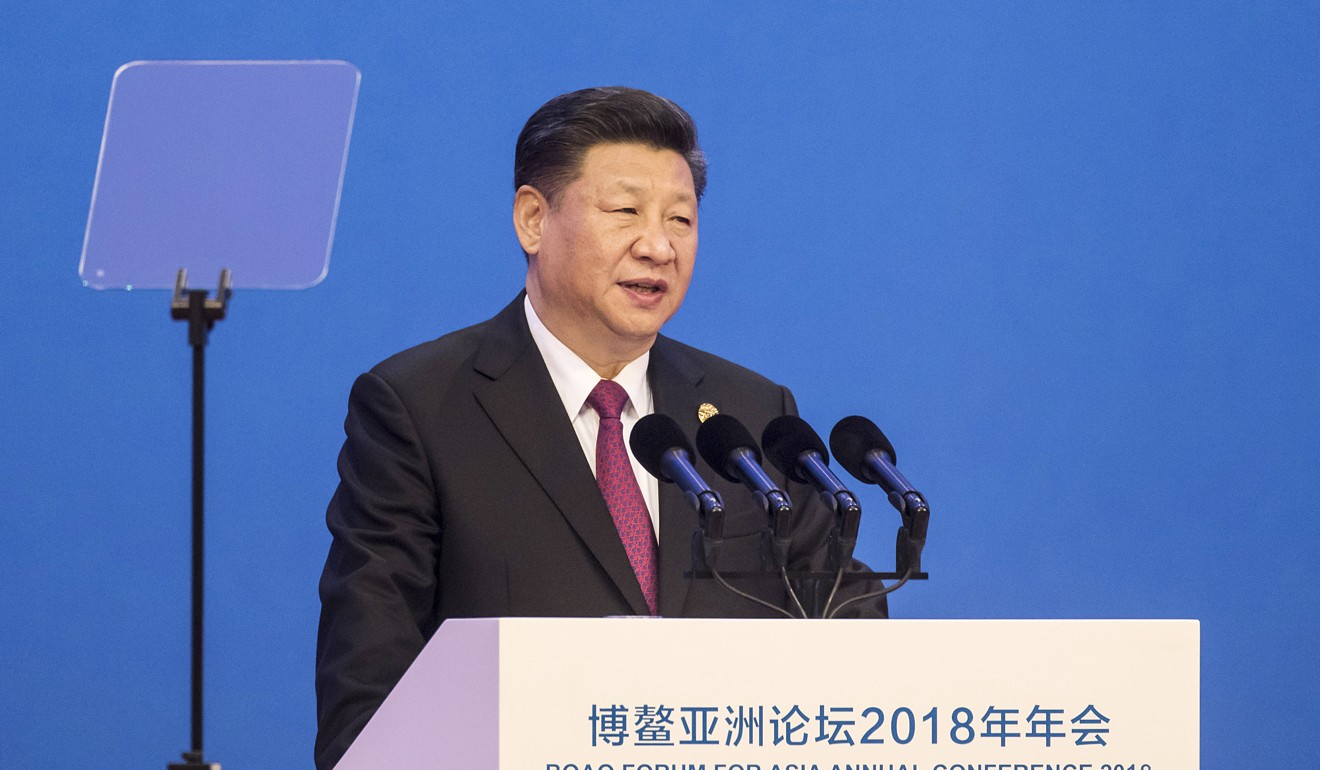

In November 2017, Trump visited Xi in Beijing. He said the two had “great chemistry”. Asked about trade, he noted it was “very one-sided”, but said, “I don’t blame China. Who can blame a country that is able to take advantage of another country for the benefit of its citizens? I give China great credit.”

Xi, hewing to Beijing’s script, talked about “win-win” cooperation and a “new starting point” for the bilateral relationship.

A few days before Trump’s trip, Tan Hock Eng, a Chinese-Malaysian based in Singapore, had announced he was getting ready to move his company, semiconductor manufacturer Broadcom, back to the US from Singapore. Tan had moved Broadcom to the city state after acquiring the company in 2016. He liked the economic policies Trump was planning and was making a bet on America. “We believe the USA presents the best place for Broadcom to create shareholder value,” Tan said.

Four days later, Broadcom launched a takeover bid for San Diego-based Qualcomm, one of the world’s leading mobile-chip makers. One of a handful of firms globally working to set the standards for 5G, the next generation of wireless communications technology, Qualcomm was competing furiously with China’s Huawei.

The timing of the announcement to return to the US just before the offer for Qualcomm looked like a way to circumvent a review of the takeover by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (CFIUS), which had been increasingly in the news over the past few years as foreign companies sought to acquire US technology firms. Qualcomm rejected Broadcom’s offer. Broadcom went “hostile”, seeking to replace Qualcomm’s directors. Qualcomm fought back: Broadcom would not invest in research and development like Qualcomm did; the US needed Qualcomm’s tech; oh, and Tan did a lot of business with Huawei.

After a four-month back-and-forth, and the announcement that CFIUS had indeed begun a review, Broadcom took steps to accelerate the timing of its move back to the US, which seemed like a way to kill the CFIUS review.

Trump did the killing instead, signing an order on March 12 to halt the takeover. It was an extraordinary occurrence, a US president stepping into the middle of a business transaction.

Tan may have been a victim of the times. His takeover of Qualcomm was unlikely to make it past Trump, especially after the US raised the stakes in December by calling out China, often in the same breath as Russia, in the National Security Council’s National Security Strategy. “China and Russia challenge American power, influence and interests, attempting to erode American security and prosperity,” the strategy report said. “They are determined to make economies less free and less fair …”

Citing the promotion of American prosperity as one of “four vital national interests”, the report stated, “We will insist upon fair and reciprocal economic relationships to address trade imbalances. The United States must preserve our lead in research and technology and protect our economy from competitors who unfairly acquire our intellectual property … [The US] will no longer tolerate economic aggression or unfair trading practices.”

It was not just a negotiating tactic in the US trade talks with Beijing. It was blunt language, a marked shift away from the conciliatory language that Obama had used in his reports, where “cooperation” was the theme, or George W. Bush’s reports, which were much the same. The country that had first come to Americans’ attention as an IP problem by pirating Madonna CDs and Microsoft Office was now a “strategic competitor”.

Apple, Amazon deny China used tiny chips to hack their networks

Now, unknown to the public, intelligence agencies were investigating a tiny chip they had found installed in the system boards of one of the world’s largest suppliers to servers that were used by major corporations such as Apple and Amazon, and in government installations in the Defense Department and Central Intelligence Agency. Apple and Amazon denied their servers had been compromised but no president charged with defending the US could ignore the apparently accumulating evidence.

On March 22, 2018, Trump announced the conclusion of the USTR’s Section 301 investigation. In a speech accompanying the release of the report, Trump indicated that the US might levy tariffs on up to US$60 billion of imports from China. Lighthizer also spoke briefly, noting that “technology is probably the most important part of our economy. There’s 44 million people who work in hi-tech knowledge areas. No country has as much technology-intensive industry as the United States. And technology is really the backbone of the future of the American economy.”

Their comments were posted on the White House website under the headline, “Remarks by President Trump at Signing of a Presidential Memorandum Targeting China’s Economic Aggression.” There it was again: “Economic Aggression”. Lighthizer’s next step was to determine on which imports he would levy tariffs.

On April 3, the contest to see whose tariff was bigger started when the US released a list of more than 1,000 products imported from China – about US$50 billion worth – that it was considering for 25 per cent tariffs. Transparent and frank, Lighthizer laid out how the products had been selected: “Trade analysts from several US government agencies identified products that benefit from Chinese industrial policies, including Made in China 2025. The list was refined by removing […] products […] likely to cause disruptions to the US economy […] then selecting products […] with lowest consumer impact.”

The next day, Trump upped the stakes. “Rather than remedy its misconduct, China has chosen to harm our farmers and manufacturers,” he said in a statement. “In light of China’s unfair retaliation, I have instructed the USTR to consider whether US$100 billion of additional tariffs would be appropriate …”

The retaliatory tariffs produced a visceral, Pavlovian response from American economists, bankers, diplomats, chief executives and anyone else who made money trading with China: tariffs were bad, and that was that. But while they were unanimous in condemning tariffs, they were also unanimous in lacking alternatives to tackle the IP problem. So, what to do?

Tariffs are the bluntest of instruments and not designed to address the IP problem directly. All they really do is punish China. Yet a promise from Beijing to fix the problem no longer seems like it will be accepted.

Over the next month, the two sides went back and forth, meeting in Beijing and Washington, talking hopefully one day, blaming each other the next in what The New York Times called, “a dizzying trade dispute that has pitted the world’s two largest economies against each other and resulted in a seemingly endless game of one-upmanship”.

On June 18, Trump announced he was ready to impose 10 per cent tariffs on another US$200 billion of Chinese imports, and to go even higher if Beijing kept fighting back.

Extraordinarily, in China voices were going public not only to question Beijing’s handling of the dispute but its overall handling of the economy and even its much-hyped technological prowess. Liu Yadong, editor-in-chief of Science and Technology Daily, speaking in Beijing in June, said China’s technology really was not so advanced and the leadership should stop claiming it was.

China, US should move forward with ‘respect, equality’ says Chinese Premier

But it is too late for that. Nobody believes Beijing will alter China’s goals or the pursuit of them, which is why it is hard to see where negotiations are going.

On August 1, Lighthizer announced that Trump instructed him to consider raising the 10 per cent tariffs on US$200 billion of imports from China to 25 per cent. Since the tariffs took effect in July, the two sides have not met on trade.

Pence accused Beijing of meddling in the upcoming midterm elections in the US. The weekend before his speech, the American edition of the China Daily newspaper placed a four-page insert in Iowa’s Des Moines Register, with headlines like, “Book tells of Xi’s fun days in Iowa”, and, “Dispute: Fruit of a President’s folly.” Targeting exports from states that are largely considered Trump’s base, and then blaming their president? As divided as Americans are right now, it is a stretch to think many of them would prefer Xi’s candidates to Trump’s candidates on election day.

Last month, one of China’s leading liberal economists, Zhang Weiying, a professor at Peking University, gave a lecture in which he said that using the “China model” – a powerful one-party state, a colossal state sector and “wise” industrial policy – to explain the country’s economic success over the past four decades was wrong and dangerous. Most of the West shares that view.

Western post-war institutions have focused on building a global economic order that would ensure events like those that led to the second world war would never happen again. When Beijing asked, China was welcomed into these institutions and benefited enormously from trading with the liberal democracies. In a quarter of a century, a singular focus on the economy by Beijing brought China a long way on the road to prosperity. What was bad about that?

The US seems no longer willing to tolerate practices Beijing employed to do this. The Chinese Communist Party holds itself up as being responsible for lifting more people out of poverty faster than ever before in history, but it had a lot of help from the world’s universities, trading institutions, and investors – none more so than those in the US. Going from the economy of today, with 600 million still very poor people around the country, to real, full prosperity, without its largest customer, may be much harder.

Since pulling out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) on Trump’s first day in office, the US has signed a new bilateral trade deal with South Korea and renegotiated the North American Free Trade Agreement with Canada and Mexico. Trump’s trade team is working towards deals with the European Union, Britain, Japan, Australia and New Zealand. Completing agreements with this last trio would mean they will have effectively made trade agreements with 95 per cent of the economies of the TPP. Presumably, the US side will focus on getting the good from these agreements while leaving behind the bad.

It is brutal, self-interested politics – America first – but that is what Trump said he would do.

Trump offers to host Xi for dinner at G20 summit

But how strong can an alliance be when the president of the US has been so disrespectful of diplomacy’s norms while patching it together in a series of smaller deals. For all the problems, a grouping, such as the TPP, gives a unity and transparency that a series of smaller deals cannot.

China’s leaders still say they have no idea what Trump wants, which could well be what Trump wants. During the campaign, he talked about how “stupid” it was for the military to announce moves such as its plans to attack Isis in Syria. It is not unlikely that he views economic negotiations with China the same way.

It has been an article of faith among many in the US political and diplomatic class that transparency – saying exactly what the US is going to do and then doing it – is often the best course for the world leader. While that has advantages, it also assumes the other side will, at some level, have an appreciation of forthrightness. Given the history of trade negotiations with China, Trump may think it is as stupid to tell Beijing what he is doing on the economic front as it is to tell Isis the time and place of the next cruise-missile strike.

Despite his enemies’ constant mocking of his intelligence, Trump is not a stupid man. One does not have to be an intellectual to be smart. Trump sees a macro issue and he wants to address it. Time will tell if he is making the right moves in dealing with Beijing on trade, which is more a question of technology transfer than trade balance.

One thing he does know is that doing nothing is not the answer. It is possible that he may never give clear articulation to what he is doing, but it is just as possible that all China’s leaders had to do to understand Trump was listen to him.

He began saying how he would address the China trade problem the day he announced his candidacy for president. And he has been doing so ever since.