Hugo Young

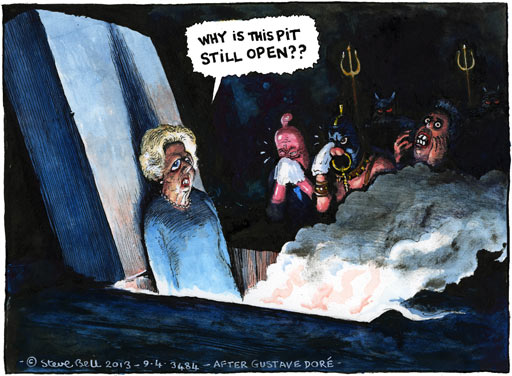

"Margaret Thatcher left a dark legacy that has still not disappeared"

The first time I met Margaret Thatcher, I swear she was wearing gloves. The place was her office at the Department of Education, then in Curzon Street. Maybe my memory is fanciful. Perhaps she had just come inside.

But without any question, sitting behind her desk, she was wearing a hat. The time was 1973. This was the feminine creature who, two years later, was leader of the Conservative party. Steely, certainly. The milk snatcher reputation absorbed and lived with. Lecturing me about the comprehensive schools, of which she created more than any minister before or since. But a woman who, at the time, thought that chancellor was the top mark at which she might aim. Conscious of being a woman, and incapable of pretending otherwise. Indeed a person – with a chemistry that repelled almost all the significant males in Edward Heath's cabinet – who could never become the party leader.

Being a woman is undoubtedly one of the features, possibly the most potent, that makes her ascent to power memorable, 25 years on, in a way that applied to no man. Harold Macmillan, Alec Douglas-Home, Heath: they seem, by comparison, evanescent figures.

Thatcher is remembered for her achievements, but more for a presence, which was wrapped up with being a woman. Several strong women on the continent have risen to the top, but this British woman, in Britain of all places, became a phenomenon, first, through her gender.

The woman, however, changed. The gender remained, its artefacts deployed with calculation. But it was overlaid by the supposedly masculine virtues, sometimes more manly than the men could ever assemble. She became harder than hard. Sent Bobby Sands to an Irish hero's grave without a blink. Faced down trade union leaders after her early years – apprentice years, when Jim Callaghan's Britain was falling apart – in which the commonest fear was that the little lady would not be able to deal with them across the table.

Thatcher became a supremely self-confident leader. No gloves, or hats, except for royalty or at funerals, but feet on the table, whisky glass at hand, into the small hours of solitude, for want of male cronies in the masculine world she dominated for all her 11 years in power.

Draining down those 11 years to their memorable essence, what does one light upon? What is really left by Thatcher to history? What will not be forgotten? What, in retrospect, seems creative and what destructive? Are there, even, things we look back on with regret for their passing? Would we like her back?

I think by far her greatest virtue, in retrospect, is how little she cared if people liked her. She wanted to win, but did not put much faith in the quick smile. She needed followers, as long as they went in her frequently unpopular directions. This is a political style, an aesthetic even, that has disappeared from view. The machinery of modern political management – polls, consulting, focus groups – is deployed mainly to discover what will make a party and politician better liked, or worse, disliked. Though the Thatcher years could also be called the Saatchi years, reaching a new level of presentational sophistication in the annals of British politics, they weren't about getting the leader liked. Respected, viewed with awe, a conviction politician, but if liking came into it, that was an accident.

This is a style whose absence is much missed. It accounted for a large part of the mark Thatcher left on Britain. Her unforgettable presence, but also her policy achievements. Mobilising society, by rule of law, against the trade union bosses was undoubtedly an achievement. For the most part, it has not been undone. Selling public housing to the tenants who occupied it was another, on top of the denationalisation of industries and utilities once thought to be ineluctably and for ever in the hands of the state. Neither shift of ownership and power would have happened without a leader prepared to take risks with her life. Each now seems banal. In the prime Thatcher years they required a severity of will to carry through that would now, if called on, be wrapped in so many cycles of deluding spin as to persuade us it hadn't really happened.

These developments set a benchmark. They married the personality and belief to action. Britain was battered out of the somnolent conservatism, across a wide front of economic policies and priorities, that had held back progress and, arguably, prosperity. This is what we mean by the Thatcher revolution, imposing on Britain, for better or for worse, some of the liberalisation that the major continental economies know, 20 years later, they still need. I think on balance, it was for the better, and so, plainly did Thatcher's chief successor, Tony Blair. If a leader's record is to be measured by the willingness of the other side to decide it cannot turn back the clock, then Thatcher bulks big in history.

But this didn't come without a price. Still plumbing for the essence, we have to examine other bits of residue. Much of any leader's record is unremarkable dross, and Thatcher was no exception. But keeping the show on the road is what all of them must first attend to, because there's nobody else to do it. Under this heading, Thatcher left a dark legacy that, like her successes, has still not disappeared behind the historical horizon. Three aspects of it never completely leave my head.

The first is what changed in the temper of Britain and the British. What happened at the hands of this woman's indifference to sentiment and good sense in the early 1980s brought unnecessary calamity to the lives of several million people who lost their jobs. It led to riots that nobody needed. More insidiously, it fathered a mood of tolerated harshness. Materialistic individualism was blessed as a virtue, the driver of national success. Everything was justified as long as it made money – and this, too, is still with us.

Thatcherism failed to destroy the welfare state. The lady was too shrewd to try that, and barely succeeded in reducing the share of the national income taken by the public sector. But the sense of community evaporated. There turned out to be no such thing as society, at least in the sense we used to understand it. Whether pushing each other off the road, barging past social rivals, beating up rival soccer fans, or idolising wealth as the only measure of virtue, Brits became more unpleasant to be with. This regrettable transformation was blessed by a leader who probably did not know it was happening because she didn't care if it happened or not. But it did, and the consequences seem impossible to reverse.

Second, it's now easier to see the scale of the setback she inflicted on Britain's idea of its own future. Nations need to know the big picture of where they belong and, coinciding with the Thatcher appearance at the top, clarity had apparently broken through the clouds of historic ambivalence.

Heath took us into Europe, and a referendum in spring 1975 confirmed national approval for the move. Prime Minister Thatcher inherited a settled state of British Europeanness, in which Brussels and the [European] Community began to influence, and often determine, the British way of doing things. She added layers of her own to this intimacy, directing the creation of a single European market that surrendered important national powers to the collective.

But on the subject of Europe, Thatcher became a contradictory figure. She led Britain further into Europe, while talking us further out. Endeavouring to persuade the British into an attitude of hostility to the group with which she spent 11 years deepening their connection must take a high place in any catalogue of anti-statesmanship. This, too, we still live with.

One also can't forget what happened to the agency that made Thatcher world‑famous: the Conservative party, of which she seemed such an improbable leader. Without it, she would have been nothing. It chose her in a fit of desperation, hats and all – though it quite liked the hats. It got over a deep, instinctive hostility to women at the top of anything, and put her there. Yet her long-term effect seems to have been to destroy it. The party she led three times to electoral triumph became unelectable for a generation.

There are many reasons for this. But Thatcher was a naturally, perhaps incurably, divisive figure. It was part of her conspicuous virtue, her indifference to familiar political conventions. It came to a head over her most egregious policy failure, Europe. She lost seven cabinet ministers on the Europe question, a record that permeated the party for years afterwards. It still does. So the woman I met in Curzon Street, dimpling elegantly, can now be seen in history with an unexpected achievement to her credit. She wrecked her own party, while promoting, via many a tortuous turn, Labour's resurrection.

The last time I met her was after all this was over. We had had a strange relationship. She continued for some reason to consider me worth talking to. Yet I wrote columns of pretty unremitting hostility to most of what she did. It became obvious that, while granting that I had "convictions", she never read a word of my stuff.

For years, in fact, she despised writers, except those who did her speeches. Why don't you get a proper job, she once sneered at me. Yet, at that last encounter, her tone was different. She had just finished the first volume of her memoirs, which she insisted was all her own work. This has been a terrible labour, she said. It was all very well for me to write books. I was a professional writer. She was not a writer. It came very hard, getting the words and paragraphs in the right order, a task for which, she eventually admitted, she had hired some help.

But now the history was what mattered. Getting the record straight.

Making sure the verdict wasn't purloined by others. Everything has its season. Promises. Action. Words. Hats. Gloves. Handbag. Now it was the turn of the words, and no one, of course, would, against all the odds, do them better than the lady who, 25 years before, once thought the sky was beyond her limit.

Hugo Young was a political columnist for the Guardian from 1984 until 2003 and biographer of Margaret Thatcher. He wrote this piece in 2003, two weeks before he died.

Glenn Greenwald

"This demand for respectful silence in the wake of a public figure's death is not just misguided but dangerous"

News of Margaret Thatcher's death this morning instantly and predictably gave rise to righteous sermons on the evils of speaking ill of her. British Labour MP Tom Watson decreed: "I hope that people on the left of politics respect a family in grief today." Following in the footsteps of Santa Claus, Steve Hynd quickly compiled a list of all the naughty boys and girls "on the left" who dared to express criticisms of the dearly departed Prime Minister, warning that he "will continue to add to this list throughout the day". Former Tory MP Louise Mensch, with no apparent sense of irony, invoked precepts of propriety to announce: "Pygmies of the left so predictably embarrassing yourselves, know this: not a one of your leaders will ever be globally mourned like her."

This demand for respectful silence in the wake of a public figure's death is not just misguided but dangerous. That one should not speak ill of the dead is arguably appropriate when a private person dies, but it is wildly inappropriate for the death of a controversial public figure, particularly one who wielded significant influence and political power. "Respecting the grief" of Thatcher's family members is appropriate if one is friends with them or attends a wake they organize, but the protocols are fundamentally different when it comes to public discourse about the person's life and political acts. I made this argument at length last year when Christopher Hitchens died and a speak-no-ill rule about him was instantly imposed (a rule he, more than anyone, viciously violated), and I won't repeat that argument today; those interested can read my reasoning here.

But the key point is this: those who admire the deceased public figure (and their politics) aren't silent at all. They are aggressively exploiting the emotions generated by the person's death to create hagiography. Typifying these highly dubious claims about Thatcher was this (appropriately diplomatic) statement from President Obama: "The world has lost one of the great champions of freedom and liberty, and America has lost a true friend." Those gushing depictions can be quite consequential, as it was for the week-long tidal wave of unbroken reverence that was heaped on Ronald Reagan upon his death, an episode that to this day shapes how Americans view him and the political ideas he symbolized. Demanding that no criticisms be voiced to counter that hagiography is to enable false history and a propagandistic whitewashing of bad acts, distortions that become quickly ossified and then endure by virtue of no opposition and the powerful emotions created by death. When a political leader dies, it is irresponsible in the extreme to demand that only praise be permitted but not criticisms.

Whatever else may be true of her, Thatcher engaged in incredibly consequential acts that affected millions of people around the world. She played a key role not only in bringing about the first Gulf War but also using her influence to publicly advocate for the 2003 attack on Iraq. She denounced Nelson Mandela and his ANC as "terrorists", something even David Cameron ultimately admitted was wrong. She was a steadfast friend to brutal tyrants such as Augusto Pinochet, Saddam Hussein and Indonesian dictator General Suharto ("One of our very best and most valuable friends"). And as my Guardian colleague Seumas Milne detailed last year, "across Britain Thatcher is still hated for the damage she inflicted – and for her political legacy of rampant inequality and greed, privatisation and social breakdown."

To demand that all of that be ignored in the face of one-sided requiems to her nobility and greatness is a bit bullying and tyrannical, not to mention warped. As David Wearing put it this morning in satirizing these speak-no-ill-of-the-deceased moralists: "People praising Thatcher's legacy should show some respect for her victims. Tasteless." Tellingly, few people have trouble understanding the need for balanced commentary when the political leaders disliked by the west pass away. Here, for instance, was what the Guardian reported upon the death last month of Hugo Chavez:

"To the millions who detested him as a thug and charlatan, it will be occasion to bid, vocally or discreetly, good riddance."

Nobody, at least that I know of, objected to that observation on the ground that it was disrespectful to the ability of the Chavez family to mourn in peace. Any such objections would have been invalid. It was perfectly justified to note that, particularly as the Guardian also explained that "to the millions who revered him – a third of the country, according to some polls – a messiah has fallen, and their grief will be visceral." Chavez was indeed a divisive and controversial figure, and it would have been reckless to conceal that fact out of some misplaced deference to the grief of his family and supporters. He was a political and historical figure and the need to accurately portray his legacy and prevent misleading hagiography easily outweighed precepts of death etiquette that prevail when a private person dies.

Exactly the same is true of Thatcher. There's something distinctively creepy - in a Roman sort of way - about this mandated ritual that our political leaders must be heralded and consecrated as saints upon death. This is accomplished by this baseless moral precept that it is gauche or worse to balance the gushing praise for them upon death with valid criticisms. There is absolutely nothing wrong with loathing Margaret Thatcher or any other person with political influence and power based upon perceived bad acts, and that doesn't change simply because they die. If anything, it becomes more compelling to commemorate those bad acts upon death as the only antidote against a society erecting a false and jingoistically self-serving history.

Polly Toynbee

"What matters to us is her legacy now that her heirs and imitators rule in her wake. The Cameron and Osborne circle are crude copies carried away with the dangerous idea that conviction is all it takes to run a country"

All can agree that Margaret Thatcher changed the heart of British politics more than any politician since Clement Attlee. She all but erased his political legacy to stamp her own image on the nation, so Britain before and after Thatcher were two different countries. Where once we stood within a recognisable postwar social democratic European tradition, after Thatcher the country had rowed halfway across the Atlantic, psychologically imbued with US neoliberal individualism. Too timid, too in thrall, the 13-year Labour government rarely dared challenge the attitudes she planted in the national psyche.

In a twitter of panic, Labour shadow ministers sent out pleas yesterday: "Hoping all Labour supporters will respond with dignity and respect to news of Baroness Thatcher's death." Dignity and decorum ruled the day - except in the poisoned anonymity of the internet. She certainly was divisive, bisecting the country politically and geographically: hard-hit regions in the north of England, Wales and Scotland may be notably less civil in their farewells. But every prime minister since has bowed to her legacy, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown eager to be snapped with her on their doorstep. The pomp and circumstance that will crown her funeral was proffered by Brown, to some shudders from his own side.

Superlatives can be agreed: a remarkable first woman PM; the first winner of three elections in a row; brave; tough; relentless; clever; sleeplessly driven by a self-confident conviction that overawed her enemies. Every quality had its obverse, but she had a myth-making charisma to capture the world's imagination. Watch a million words pour out today placing her anywhere from Boudicca to the wicked witch of the west.

That's history, but what matters to us is her legacy now that her heirs and imitators rule in her wake. The Cameron and Osborne circle are crude copies carried away with the dangerous idea that conviction is all it takes to run a country. Seizing her chariot's reins to drive it on recklessly, they lack her brains, experience and political skill. Above all, they lack her competence at running the machinery of government. Thanks to the comparison with Cameron, we are reminded that the Thatcher reign was more circumspect and well-managed than it seemed at the time. Until her final poll-tax hubris, she knew when swerving was the better part of valour and despite that famous one-liner, she was sometimes for turning. Her imitators swerve all over the place, with 37 U-turns at the Telegraph's latest count on matters from forests and pasties to buzzard nests and caravans. But on their catastrophic economic policy, it's full-speed ahead into the concrete wall. She would, say some who knew her, have a found a way to finesse a change of direction by now.

The romantic image of the lady in the tank spurs them on. Where she privatised state-owned industries, they go much further, seeking to dismantle the state itself. She usually knew the limits to public tolerance, gauging how much of the spirit of '45 abided, so even if it was between gritted teeth, she forced herself to say, "The NHS is safe in our hands": she reorganised but did not privatise it. No such alarms ring in Cameron's ears.

The Cameron generation wrongly see in the 1980s a revolution to emulate, starting with an economic crisis just like hers, as a chance to reshape everything. But look at this typical difference between her and her imitators: where Cameron has charged into Europe, taking his party out of the influential European People's party of natural allies, making enemies and building no useful coalitions, it was she who signed the Single European Act, understanding its importance for British trade, careful to make allies as well as swinging her handbag. Not until well out of office, angry and lacking her old judgment, did she lead the rabidly Eurosceptic renegades.

While some remember her as a national saviour, others only see her ruthless demolition of flailing state-owned industries. As coal, steel and shipbuilding fell under her wrecking ball, whole communities were destroyed. Was it cruelty? Tim Bale, author of The Conservative Party: from Thatcher to Cameron, says it was conviction. She fervently believed the market would soon repair their loss. Creative destruction was capitalism's necessary agent, so equilibrium was bound to be restored. It never was. Large parts of society never recovered, while Germany and other countries managed the transition without such brutality. North sea oil was squandered when it should have seeded new industries. Instead, her Big Bang blew the roof off City profits and property booms filled the gap where productive industry should have sprouted. Her heirs have not learned that lesson, with no sign of their promised "rebalancing". No sign they learned from her that markets don't move in to fill the gaps when the state is rolled back – not then, not now.

When she walked into Downing Street promising harmony instead of discord, only one in seven children was poor and Britain was more equal than at any time in modern history. But within a few years, a third of children were poor, a sign of the yawning inequality from which the country never recovered.

True, Labour, James Callaghan and the unions played their part by blocking Barbara Castle's In Place of Strife attempt to create German or Nordic co-operation between unions and industry that might have rescued unions from Thatcher's crushing. The tragic upshot has been the steep erosion of wages for the powerless bottom half, as income, wealth and property is sucked up to the top.

The endemic worklessness of her era was never repaired – now her successors blame the victims. Cameron's crew crudely imagine she intended it. That gives them the nerve to set about cutting benefits and the public realm with a glee they don't bother to hide. They are acolytes of a raw Thatcher cult they have rough-hewn and exaggerated in their own image. In towns and valleys poleaxed by the Iron Lady, there may be glasses raised at her passing. She will be for ever unforgiven by those who now see worse being done in her name to another generation. She undoubtedly rescued the prestige of the country from its postwar nadir, but at a high cost to the generosity of its political and social culture.

Jonathan Freedland

"This debate over how to remember Margaret Thatcher – whether on the streets, on Twitter or at next Wednesday's funeral – is not about the past"

Back when we called her Maggie, when it seemed she would have her wish and "go on and on" in ruling the country, her opponents would lament some new step towards social ruin with the withering, two-word verdict: "Thatcher's Britain."

It was meant as a term of condemnation, a concise way of arguing that riots in the street or the devastation of a pit village were the inevitable features of this new land that had arisen in the 1980s, a country reshaped by the woman at the top.

Curiously, the phrase does not sound as dated as it should. That's because, 23 years after she was ejected from Downing Street by her own party in a move whose psychic wounds linger on, the country we live in remains Thatcher's Britain. We still live in the land Margaret built.

Just look around. Visit a station and notice the plethora of competing train companies, replacing the single British Rail that operated in the pre-Thatcher days – the fruit of a rail privatisation that was not hers, but was made possible only by the serial privatisations she had pioneered and made normal. Look at the cars on the road, none made by the old, nationally-owned British Leyland and only few by the British marques that once dominated but which went the way of much of British industry – unable to survive the chill wind of "market forces", another phrase which filled the air back then.

Look inside your own house, at the water coming out of the tap: once a public utility but, after Thatcher, the property of private companies, many foreign-owned. Gaze at the telephone. When she took over in 1979, the bottom of that device would have carried the legend, "Property of the GPO." It was not yours, but belonged to the Post Office: in effect, the government. What's more, it was moulded to the wall – as one commentator recalled – and you had no right to change it, not without becoming entangled in a state-managed bureaucracy. That was before Thatcher modishly renamed the service British Telecom and sold it off.

Viewed from today, that past Britain is indeed a foreign country. In her 1982 party conference speech, Margaret Thatcher offered a prediction for the future: "How absurd it will seem in a few years' time that the state ran Pickfords removals and Gleneagles Hotel." Absurd or not, it does indeed seem alien – not least to those born in the 1980s, the generation we shall always call Thatcher's children.

Selling off the family silver Harold Macmillan – and later Labour – called it, as Margaret Thatcher set about reversing the 1945 nationalisations that had put oil, gas, coal, electricity and an airline as well as a house removal company in public hands.

For some, the only consequence of that shift, still visible today, will be a changed brand name or higher bills. But for others, the change in landscape is all too real. Across Yorkshire or south Wales, Kent or Nottinghamshire, there are villages that have never recovered from the closure of coal mines, ordered by a Thatcher who ruled there was no place for pits that were not "economically viable", regardless of the social consequences. Some places have become heritage parks, remembering an industry now vanished. But other villages have never recovered, their heart and purpose ripped out. Those abandoned places are also landmarks in Thatcher's Britain.

To have achieved all this alone would have made Margaret Thatcher a towering, transformational figure, one who altered the physical fabric of the nation. But these concrete achievements do not wholly explain why she still looms so large, large enough that not one but two current West End plays – The Audience and Billy Elliot – grant Thatcher a pivotal, if largely unsympathetic, role, whether seen or unseen.

For she changed the ethos of Britain as well as its landscape. In 2009, Boris Johnson lamented that Thatcher had become "a boo-word in British politics, a shorthand for selfishness and me-first-ism, and devil-take-the-hindmost and grinding the faces of the poor."

The London mayor regretted that usage, but he surely understood its origins. The set text is still Thatcher's declaration – quoted in The Audience – that "There is no such thing as society". Her defenders always insisted that sentence had been misunderstood, but it stuck because it seemed to capture something essential about the Thatcherite creed: its embrace of individualism and apparent disdain for the collective.

At its best, that has meant a mood of freedom and choice that has made these islands a brighter, less drab place than they once were. One might even credit Thatcher with a willingness to jettison the old rules and conventions that used to prevent individuals deciding their own destiny. For her own part, she was a social conservative – and yet today's right for, say, gay couples to marry if they want to fits with one aspect of the Thatcherite vision of personal choice.

But at its crudest, the Thatcher ethos translated into the get-rich-quick, greed-is-good spirit of the 1980s, satirised by Harry Enfield's Loadsamoney creation. The Big Bang of City deregulation, the Tell Sid scramble for buying and selling shares, the sense that money is the highest value, wealth the greatest sign of worth – all these were hallmarks of the Thatcher era in its mid-80s pomp. Few would argue that they have not endured. On the contrary, consumerism and materialism have been the norm ever since, rising inequality the consistent trend as the rich soar ever further away from the rest. Moreover, it's hard not to see the roots of the 2008 crash in the unshackling of the City two decades earlier.

More subtly, Thatcher bequeathed a kind of instinctive rejection of once-valued forms of collective activity. Her onslaught on the trade unions left those movements pale imitations of their former selves, too weak to resist the drive to the "flexible labour market" which has seen Britain become the home of what one senior Labour figure calls "crappy jobs", with low pay and no protection.

But there are less obvious manifestations of the same habit. Witness the steady downgrading of local government or the persistent assumption that the private sector will always be better than the public. As the coalition sets about shrinking the welfare state, it's still embarked on Thatcher's project of rolling back the frontiers of the state, dismantling the settlement that held from 1945 until it unravelled in the 1970s.

Of course, it's in politics that the shadow looms most clearly. Today's Tories walk in Thatcher's footsteps, battling with their estranged cousins in Ukip over who is the rightful heir to her Eurosceptic legacy. But Labour is no less in thrall. The Lady forced the opposition party to accommodate itself to the new, Thatcherite settlement in which the market would rule unless stated otherwise. It's telling that Tony Blair's domestic legacy amounts to two responses to Thatcherism: forcing Labour to accept it and then compensating for the damage the Tories had wreaked through sustained underinvestment in the public realm. She had left a Britain marked by private affluence and public squalor. It fell to Blair to do something about the latter, while giving free rein to the former.

So look around this kingdom of ours, at a devolved Scotland contemplating independence – a state of affairs that owes much to Thatcher's antagonistic relationship with that country. Look at the trains on the track, the phone in your house, the trio of 1980s teenagers who lead the three main parties. What you see is a nation ruled for 11 turbulent years by a remarkable woman – and which still lives in her image.

Ian McEwan

"What bound all opposition to Margaret Thatcher's programme was a suspicion that the grocer's daughter was intent on monetising human value"

"Maggie! Maggie! Maggie! Out! Out! Out!" That chanted demand of the left has been fully and finally met. At countless demonstrations throughout the 80s, it expressed a curious ambivalence – a first name intimacy as well as a furious rejection of all she stood for. "Maggie Thatcher" – two fierce trochees set against the gentler iambic pulse of Britain's postwar welfare state. For those of us who were dismayed by her brisk distaste for that cosy state-dominated world, it was never enough to dislike her. We liked disliking her. She forced us to decide what was truly important.

In retrospect, in much dissenting commentary there was often a taint of unexamined sexism. Feminists disowned her by insisting that though she was a woman, she was not a sister. But what bound all opposition to Margaret Thatcher's programme was a suspicion that the grocer's daughter was intent on monetising human value, that she had no heart and, famously, cared little for the impulses that bind individuals into a society.

But if today's Guardian readers time-travelled to the late 70s they might be irritated to discover that tomorrow's TV listings were a state secret not shared with daily newspapers. A special licence was granted exclusively to the Radio Times. (No wonder it sold 7m copies a week). It was illegal to put an extension lead on your phone. You would need to wait six weeks for an engineer. There was only one state-approved answering machine available. Your local electricity "board" could be a very unfriendly place. Thatcher swept away those state monopolies in the new coinage of "privatisation" and transformed daily life in a way we now take for granted.

We have paid for that transformation with a world that is harder-edged, more competitive, and certainly more intently aware of the lure of cash. We might now be taking stock, post credit crunch, of our losses and gains since the 1986 deregulation of the City, but it is doubtful that we will ever undo her legacy.

It is odd to reflect that in Thatcher's time, the British novel enjoyed a comparatively lively resurgence. Governments can rarely claim to have stimulated the arts but Thatcher, always rather impatient with the examined life, drew writers on to new ground. The novel may thrive in adversity and it was a general sense of dismay at the new world she was showing us that lured many writers into opposition. The stance was often in broadest terms, more moral than political. Her effect was to force a deeper consideration of priorities, sometimes expressed in a variety of dystopias.

She mesmerised us. At an international conference in Lisbon in the late 80s, the British faction, among whom were Salman Rushdie, Martin Amis, Malcolm Bradbury and myself, referred back to Thatcher constantly in our presentations. Asked to report on the "state of things" in our country, we could barely see past her. Eventually, the Italian contingent, largely existential or postmodern, rose up against us. We had an all-out blistering row that delighted the organisers.

Literature had nothing to do with politics, the Italian writers said. Take the larger view. Get over her! They had a point, but they had no idea how fascinating she was – so powerful, successful, popular, omniscient, irritating and, in our view, wrong. Perhaps we suspected that reality had created a character beyond our creative reach.

Not all writers were against her. Philip Larkin visited Downing Street where the prime minister quoted approvingly one of his lines to him – "Your mind lay open like a drawer of knives." Accounts vary. She may have got it slightly wrong. Quotation being the warmest form of praise, Larkin was naturally touched.

We might speculate that an adviser had offered Thatcher a selection of good lines, or that she had asked to see some. But the choice captures her perfectly. For a start, she had a superb memory for a brief, and she would have had no problem memorising quickly any number of lines. Larkin's evoked the treacherous mind (of an adversary, of a cabinet colleague) helplessly exposed to her steely regard. One turns with gratitude to Alan Clark's diaries for a fine description of being summoned to No 10 and being subjected to just such an examination.

When the late Christopher Hitchens was a political reporter for the New Statesman, he corrected the prime minister on a point of fact, and she was quick to correct Hitchens in turn. She was right, he was wrong. In front of his journalist colleagues he was told to stand right in front of her so that she could hit him lightly with her order papers. Over the years, and through much re-telling, the story had it that Thatcher told Hitchens to bend over, and that she spanked him with her order papers.

The truth is less significant than the alteration to it. There was always an element of the erotic in the national obsession with her. From the invention of the term "sado-monetarism" through to the way her powerful ministers seemed to swoon before her, and the constant negative reiteration by her critics of her femininity, or lack of it, she exerted a glacial hold over the (male) nation's masochistic imagination. This was heightened by the suspicion that this power was not consciously deployed.

Meryl Streep's depiction of a shuffling figure, stricken and isolated by the death of her husband, Denis, may have softened memories, or formed them in the minds of a younger generation. The virtual state funeral will rehearse again our extravagant fixations. Opponents and supporters of Margaret Thatcher will never agree about the value of her legacy, but as for her importance, her hypnotic hold on us, they are bound to find common ground.

Russell Brand

"If you behave like there's no such thing as society, in the end there isn't"

One Sunday recently while staying in London, I took a stroll in the gardens of Temple, the insular clod of quads and offices between the Strand and the Embankment. It's kind of a luxury rent-controlled ghetto for lawyers and barristers, and there is a beautiful tailors, a fine chapel, established by the Knights Templar (from which the compound takes its name), a twee cottage designed by Sir Christopher Wren and a rose garden; which I never promised you.

My mate John and I were wandering there together, he expertly proselytising on the architecture and the history of the place, me pretending to be Rumpole of the Bailey (quietly in my mind), when we spied in the distant garden a hunched and frail figure, in a raincoat, scarf about her head, watering the roses under the breezy supervision of a masticating copper. "What's going on there, mate?" John asked a nearby chippy loading his white van. "Maggie Thatcher," he said. "Comes here every week to water them flowers." The three of us watched as the gentle horticultural ritual was feebly enacted, then regarded the Iron Lady being helped into the back of a car and trundling off. In this moment she inspired only curiosity, a pale phantom, dumbly filling her day. None present eyed her meanly or spoke with vitriol and it wasn't until an hour later that I dreamt up an Ealing comedy-style caper in which two inept crooks kidnap Thatcher from the garden but are unable to cope with the demands of dealing with her, and finally give her back. This reverie only occurred when the car was out of view. In her diminished presence I stared like an amateur astronomer unable to describe my awe at this distant phenomenon.

When I was a kid, Thatcher was the headmistress of our country. Her voice, a bellicose yawn, somehow both boring and boring – I could ignore the content but the intent drilled its way in. She became leader of the Conservatives the year I was born and prime minister when I was four. She remained in power till I was 15. I am, it's safe to say, one of Thatcher's children. How then do I feel on the day of this matriarchal mourning?

I grew up in Essex with a single mum and a go-getter Dagenham dad. I don't know if they ever voted for her, I don't know if they liked her. My dad, I suspect, did. He had enough Del Boy about him to admire her coiffured virility – but in a way Thatcher was so omnipotent; so omnipresent, so omni-everything that all opinion was redundant.

As I scan the statements of my memory bank for early deposits (it'd be a kid's memory bank account at a neurological NatWest where you're encouraged to become a greedy little capitalist with an escalating family of porcelain pigs), I see her in her hairy helmet, condescending on Nationwide, eviscerating eunuch MPs and baffled BBC fuddy duddies with her General Zodd stare and coldly condemning the IRA. And the miners. And the single mums. The dockers. The poll-tax rioters. The Brixton rioters, the Argentinians, teachers; everyone actually.

Thinking about it now, when I was a child she was just a strict woman telling everyone off and selling everything off. I didn't know what to think of this fearsome woman.

Perhaps my early apathy and indifference are a result of what Thatcher deliberately engendered, the idea that "there is no such thing as society", that we are alone on our journey through life, solitary atoms of consciousness. Or perhaps it was just because I was a little kid and more interested in them Weetabix skinheads, Roland Rat and Knight Rider. Either way, I'm an adult now and none of those things are on telly any more so there's no excuse for apathy.

When John Lennon was told of Elvis Presley's death, he famously responded: "Elvis died when he joined the army," meaning of course, that his combat clothing and clipped hair signalled the demise of the thrusting, Dionysian revolution of which he was the immaculate emblem.

When I awoke today on LA time my phone was full of impertinent digital eulogies. It'd be disingenuous to omit that there were a fair number of ding-dong-style celebratory messages amidst the pensive reflections on the end of an era. Interestingly, one mate of mine, a proper leftie, in his heyday all Red Wedge and right-on punch-ups, was melancholy. "I thought I'd be overjoyed, but really it's just … another one bites the dust …" This demonstrates, I suppose, that if you opposed Thatcher's ideas it was likely because of their lack of compassion, which is really just a word for love. If love is something you cherish, it is hard to glean much joy from death, even in one's enemies.

Perhaps, though, Thatcher "the monster" didn't die yesterday from a stroke, perhaps that Thatcher died as she sobbed self-pitying tears as she was driven, defeated, from Downing Street, ousted by her own party. By then, 1990, I was 15, adolescent and instinctively anti-establishment enough to regard her disdainfully. I'd unthinkingly imbibed enough doctrine to know that, troubled as I was, there was little point looking elsewhere for support. I was on my own. We are all on our own. Norman Tebbit, one of Thatcher's acolytes and fellow "Munsters evacuee", said when the National Union of Mineworkers eventually succumbed to the military onslaught and starvation over which she presided: "We didn't just break the strike, we broke the spell." The spell he was referring to is the unseen bond that connects us all and prevents us from being subjugated by tyranny. The spell of community.

Those strikes were confusing to me as a child. All of the Tory edicts that bludgeoned our nation, as my generation squirmed through ghoulish puberty, were confusing. When all the public amenities were flogged, the adverts made it seem to my childish eyes fun and positive, jaunty slogans and affable British stereotypes jostling about in villages, selling people companies that they'd already paid for through tax. I just now watched the British Gas one again. It's like a whimsical live-action episode of Postman Pat where his cat is craftily carved up and sold back to him.

"The News" was the pompous conduit through which we suckled at the barren baroness through newscaster wet-nurses, naturally; not direct from the steel teat. Jan Leeming, Sue Lawley, Moira Stuart – delivering doctrine with sterile sexiness, like a butterscotch-scented beige vapour. To use a less bizarre analogy: if Thatcher was the headmistress, they were junior teachers, authoritative but warm enough that you could call them "mum" by accident. You could never call Margaret Mother by mistake. For a national matriarch she is oddly unmaternal. I always felt a bit sorry for her biological children Mark and Carol, wondering from whom they would get their cuddles. "Thatcher as mother" seemed, to my tiddly mind, anathema. How could anyone who was so resolutely Margaret Thatcher be anything else? In the Meryl Streep film, The Iron Lady, it's the scenes of domesticity that appear most absurd. Knocking up a flan for Denis or helping Carol with her algebra or Mark with his gun-running, are jarring distractions from the main narrative; woman as warrior queen.

It always struck me as peculiar, too, when the Spice Girls briefly championed Thatcher as an early example of girl power. I don't see that. She is an anomaly; a product of the freak-onomy of her time. Barack Obama, interestingly, said in his statement that she had "broken the glass ceiling for other women". Only in the sense that all the women beneath her were blinded by falling shards. She is an icon of individualism, not of feminism.

I have few recollections of Thatcher after the slowly chauffeured, weepy Downing Street cortege. I'd become a delinquent, living on heroin and benefit fraud.

There were sporadic resurrections. She would appear in public to drape a hankie over a model BA plane tailfin because she disliked the unpatriotic logo with which they'd replaced the union flag (maybe don't privatise BA then), or to shuffle about some country pile arm in arm with a doddery Pinochet and tell us all what a fine fellow he was. It always irks when rightwing folk demonstrate in a familial or exclusive setting the values that they deny in a broader social context. They're happy to share big windfall bonuses with their cronies, they'll stick up for deposed dictator chums when they're down on their luck, they'll find opportunities in business for people they care about. I hope I'm not being reductive but it seems Thatcher's time in power was solely spent diminishing the resources of those who had least for the advancement of those who had most. I know from my own indulgence in selfish behaviour that it's much easier to get what you want if you remove from consideration the effect your actions will have on others.

Is that what made her so formidable, her ability to ignore the suffering of others? Given the nature of her legacy "survival of the fittest" – a phrase that Darwin himself only used twice in On the Origin of Species, compared to hundreds of references to altruism, love and cooperation, it isn't surprising that there are parties tonight in Liverpool, Glasgow and Brixton – from where are they to have learned compassion and forgiveness?

The blunt, pathetic reality today is that a little old lady has died, who in the winter of her life had to water roses alone under police supervision. If you behave like there's no such thing as society, in the end there isn't. Her death must be sad for the handful of people she was nice to and the rich people who got richer under her stewardship. It isn't sad for anyone else. There are pangs of nostalgia, yes, because for me she's all tied up with Hi-De-Hi and Speak and Spell and Blockbusters and "follow the bear". What is more troubling is my inability to ascertain where my own selfishness ends and her neo-liberal inculcation begins. All of us that grew up under Thatcher were taught that it is good to be selfish, that other people's pain is not your problem, that pain is in fact a weakness and suffering is deserved and shameful. Perhaps there is resentment because the clemency and respect that are being mawkishly displayed now by some and haughtily demanded of the rest of us at the impending, solemn ceremonial funeral, are values that her government and policies sought to annihilate.

I can't articulate with the skill of either of "the Marks" – Steel or Thomas – why Thatcher and Thatcherism were so bad for Britain but I do recall that even to a child her demeanour and every discernible action seemed to be to the detriment of our national spirit and identity. Her refusal to stand against apartheid, her civil war against the unions, her aggression towards our neighbours in Ireland and a taxation system that was devised in the dark ages, the bombing of a retreating ship – it's just not British.

I do not yet know what effect Margaret Thatcher has had on me as an individual or on the character of our country as we continue to evolve. As a child she unnerved me but we are not children now and we are free to choose our own ethical codes and leaders that reflect them.

Ken Capstick

"For miners to be referred to as the 'enemy within' was something they would never forgive and, if there is rejoicing at her death in those communities she set out to destroy, it can only be understood against this background"

In 1984 Britain had 186 working coalmines and approximately 170,000 coalminers. Today we have four coalmines and around 2,000 miners. They lived in close-knit communities built around and based on employment at the local colliery. Miners were a hardy race of people who faced constant danger in the cause of mining coal but underneath that they were caring, sensitive individuals with a commitment to the communities in which they lived. They looked after their old and young as well as those who were ill or infirm.

They built and provided their own welfare facilities and, well before today's welfare state was built, miners created their own welfare systems to alleviate hardship. They rallied around each other when times were hard. They recognised the need for cohesion when at any time disaster could strike a family unit or indeed a whole community. The latest pit to close, Maltby in Yorkshire, still has a death and general purpose fund to help fellow miners and their families in times of hardship. In short, miners believed in society.

These values were the exact opposite of those Margaret Thatcher espoused. For miners, greed was a destructive force, not a force for good. From the valleys of Wales to the far reaches of Scotland, miners were, by and large, socialists by nature but this was tempered by strong Christian beliefs. Thatcher's threat to butcher the mining industry, destroy the fabric of mining communities and in particular the trade union to which miners had a bond of loyalty, was met with the fiercest resistance any government has met in peacetime.

For those miners and their families to be referred to as the "enemy within" by Thatcher was something they would never forgive and, if there is rejoicing at her death in those communities she set out to destroy, it can only be understood against this background.

Miners had always known that eventually any of the colleries would close and were always prepared to accept that as a fact of life and find employment somewhere else within the industry, but Thatcher's attack was wholesale. It was seen for what it was, nothing to do with economics, but purely an attempt to destroy the National Union of Mineworkers by wiping out the entire industry.

Thatcher exposed the sharp edges of class division in Britain and the strike of 1984/5 was as much a clash of values as it was about pit closures. Arthur Scargill and the miners represented the only opposition to the prime minister and her destructive and divisive values and, after the strike, the way was open for the most aggressive neoliberal policies. Thatcher and Reagan went on to facilitate a colossal transfer of wealth from poor to rich, leading to the world economic crash we now witness.

Thatcher was a divisive woman who created discord, not harmony.

Simon Jenkins

"I think on balance Thatcher did for Britain what was needed at the time. History will judge her, but not a country in Europe was untouched by Thatcher's example"

Margaret Thatcher was Britain's most significant leader since Churchill. In 1979 she inherited a nation that was the "sick man of Europe", an object of constant transatlantic ridicule. By 1990 it was transformed. She and her successors John Major and Tony Blair presided over a quarter century of unprecedented prosperity. If it ended in disaster, the seeds were only partly hers.

Almost everything said of Thatcher's early years was untrue, partly through her own invention. She was the daughter of a prosperous civic leader who merely began life as a "grocer". She went to a fee-paying school and to Oxford at her father's expense, gliding easily into the upper echelons of student politics.

A Tory party desperate for women helped Thatcher through the political foothills to early success as an MP. Her gender led her into government and the shadow cabinet, despite Edward Heath's aversion to her. It made her virtually unsackable as education secretary. As she said in her memoirs: "There was no one else." When Heath fell, her promoters ran her as a stalking horse because, as a woman, they thought she could not win. Thatcher became prime minister because she was a woman, not despite it.

As leader she was initially hyper-cautious. An unclubbable outsider, she allied herself to another outsider, Keith Joseph, and his free-market set. But she regarded rightwing causes as an intellectual hobby. She was an ardent pro-European, and her 1979 manifesto made no mention of radical union reform or privatisation. It was thoroughly "wet". On taking office she showered money on public sector unions, and her "cuts" were only to planned increases, mild compared with today's. Yet by the autumn of 1981 they had made her so unpopular that bets were being taken at the October party conference that she would be "gone by Christmas".

What saved Thatcher's bacon, and revolutionised her leadership, was Labour's unelectable Michael Foot – and the Falklands war. Whatever Tory historians like to claim, this was the critical turning point. By delivering a crisp, emphatic victory Thatcher showed the world, and more important herself, what a talent for solitary command could achieve. From then on she disregarded her critics and became intolerant of any who were "not one of us".

But Thatcher was still cautious. By the 1983 election she had sold off only Britoil and some council houses. The battle with the miners and leftwing councils lay ahead, as did the trauma of an IRA assassination bid. It was only in the mid-80s that she became truly radical and remotely comparable to David Cameron in 2010.

She gave Nigel Lawson at the Treasury his head – and was genuinely alarmed when he cut income tax to 40%. She hurled herself into NHS reform, changes to schools and universities, utilities privatisation and, eventually, local government reform. Each was characterised by her attention to detail. Her political antennae refused to allow her to privatise the coal industry, British Rail or the post office.

Thatcher was never insensitive to the impact of her policies on the poor. As she cut local housing budgets, she sent housing benefit soaring in compensation. She refused to reform social security, or even curb its abuse. Many of today's more controversial benefits, such as disability, date back to the 80s.

After the 1987 election, Thatcher cut an increasingly isolated figure. Rows with Lawson and Geoffrey Howe over a European currency (where she was right) presaged the final shambles of the poll tax. Until then Thatcher had shown the strength of her weakness: a dislike of consensus and aversion to debate, leading to decisive action. A senior civil servant said, "It worked because we all knew exactly what she wanted."

The poll tax showed the opposite, the weakness of Thatcher's strength. The cautious tactician was suppressed. She became deaf to all warning. On the crucial morning in November 1990, her colleagues marched individually into her room and each told her to go. It was a Charles I moment in British history. Everyone knows where they were when they heard.

Thatcher's reputation never recovered from the ruthless budgets of 1980 and 1981, or her insensitivity to colleagues. Many hated her. She was always the Spitting Image bully. Howe's "broken cricket bats" speech in the Commons was the killer blow. It was mostly foreigners who could not understand why she fell.

John Major, the "detoxification" successor, was fated to implement many of her unattempted reforms. But perhaps her greatest legacy was New Labour. The most important thing Tony Blair and Gordon Brown did for British politics was to understand the significance of Thatcherism and to decide not to reverse it, indeed to carry it forward. Their reckless private finance of public investment and services went beyond anything she dared dream of. No one noticed, but she was Blair's first guest at Downing Street in 1997.

Thatcher's most baleful influence on government was not on industries and services she privatised but those she did not. She, and Blair after her, brought an unprecedented dirigisme to the NHS, education, police and local government. She was unashamed about this, loathing localism and rejecting calls to diminish the "strong state". She hated what she called "that French phrase laissez faire". Her centralism, unequalled in Europe, descended under Blair into a morass of targetry, inefficiency and endless reorganisation. Only today are we facing the cost.

I think on balance Thatcher did for Britain what was needed at the time. History will judge her, but not a country in Europe was untouched by Thatcher's example. Under Heath and Jim Callaghan the question was widely asked: had democracies become "ungovernable"? Had pollsters and the 24/7 media forced leaders to follow opinion, not lead it?

Thatcher answered that question, re-energising the concept of democratic leadership. It was sad that she had to learn it in war, a grim example to her British and US successors. She was lucky, in her enemies and friends – notably Reagan in the Falklands conflict. She was lucky in surviving the IRA's bomb.

But she exploited her luck. She showed that modern prime ministers can still mark out room for individual manoeuvre. They do not have to charm, schmooze or play tag with the press. Government will respond to clear leadership if it knows what a leader wants. It knew what Thatcher wanted.

Richard V Allen

"She knew very well that she was an important component of what is often attributed solely to him, and in the first instance 'winning' the cold war"

Farewelling Baroness Margaret Thatcher in a proper fashion is a difficult task: she left such a deep imprint upon the world that assessing its importance demands volumes analyzing her beliefs and paying proper tribute.

One thinks now of the closing words of her splendid 2004 eulogy of Ronald Reagan, and how those words so perfectly speak a tribute to her life and works:

"We here still move in twilight. But we have one beacon to guide us that Ronald Reagan never had. We have his example. Let us give thanks today for a life that achieved so much for all of God's children."

While she spoke of his example as a beacon, she knew very well that she was an important component of what is often attributed solely to him, and in the first instance "winning" the cold war.

Unquestionably, a major component of what Reagan achieved was mirrored in what Baroness Thatcher herself achieved. A splendid synergy was created, deliberately and with just that in mind on both sides of the Atlantic. Reagan would often hasten to remind those paying tribute to his cold war strategy that it was, in the strictest sense of the term, a team effort.

As I see it, and as one who had the pleasure of knowing both, they would recognize the huge opportunity created by the presence of each in the respective national and international policy-making role. Reagan, for one, recognized the importance of Margaret Thatcher's presence as British prime minister, but would caution any discussion partner that Pope John Paul played an equally important role. And he would credit the contribution of Helmut Kohl, who rose to power in Germany in part because of the influence of Thatcher and Reagan.

Reagan and Thatcher first met in 1975, as my friend and colleague Peter Hannaford reminded me just today. Reagan, who had recently left office as governor of California, was in London to deliver a speech to the Pilgrim Society. Reagan would challenge Gerald Ford, the sitting president, the next year. Mrs Thatcher was on the way up in British political life. In November 1978, Hannaford and I organized a European fact-finding tour for Reagan, and the first stop was London.

Reagan had sought to meet with then Prime Minister James Callaghan, but the request was rejected, and bucked to then Foreign Minister David Owen. Reagan was received coolly, and the discussion was highly superficial, if only because the British side clearly did not care to engage on substance: meet for a serious discussion with a movie actor – and a "Grade B" actor at that?

Many whom Reagan encountered in public life thought of him in this way, but most politicians would love to reach even "Grade B" status. Underestimating Ronald Reagan was an error committed by many of his critics and opponents; Reagan never minded a bit, thinking that being underestimated yielded him a significant advantage. Mikhail Gorbachev, for one, learned the hard way.

But Margaret Thatcher did not hesitate, and the long, substantive lunch seemed to energize both future world leaders. Reagan was especially interested in Mrs Thatcher's domestic policy initiatives, and it was quickly established that the foreign policy views ran along parallel lines.

She, for one, never underestimated her friend from California, then a state of some 24 million.

In 1980, I made several fast round trips to London, Paris and Bonn, and, on each occasion, had the opportunity to meet with Prime Minister Thatcher. On one visit, our campaign chairman, William J Casey, later director of the CIA, came along, and we had a fruitful meeting at 10 Downing Street. The prime minister was intensely interested in the campaign, and asked many penetrating questions.

The 1978 meeting was their last in person until Mrs Thatcher became Reagan's first state visitor, 26-28 February 1981. It was a visit warmly welcomed by President Reagan, with a resplendent state nner on the first evening. In a break with tradition and protocol, Reagan decided he'd also attend the "return dinner" at the British Embassy the next evening. The task of representing the White House usually was the role of the vice-president, but in this special case, the Reagans and the Bushes both attended. On Saturday, 27 February, he wrote in his diary:

"PM getting great press … went up to the [Capitol] Hill … some of the senators tried to give her a bad time, she put them down firmly and with typical British courtesy."

Much has been written about the special significance and warmth of the British-American alliance during the two terms of Ronald Reagan. In my view, nothing said prior to her passing or since has been inaccurate in the description of this very special, warm relationship, the likes of which we may never see again. And by my own firsthand experience, it was genuine to the core. Not even the Falklands war would push it off the tracks or damage it in any way.

Speaking personally, it was a personal privilege beyond measure to have witnessed and participate in the blossoming of the special ties that continued throughout her entire time in office.

In the early 1980s, the Republican party joined with other moderate and conservative parties in the world to form the International Democrat Union. This was a historic step, and resulted in further reinforcing the US-UK alliance. At a party leaders' meeting in Washington, DC in 1985, Prime Minister Thatcher spent all day in the House of Commons, then boarded Concorde and flew to Washington to participate until late into the evening; she took such policy co-operation very seriously. On her return to London, she sent me a warm and complimentary letter, a prize in my personal archives.

Two especially forceful and committed leaders on the world stage at the same time: this was critical and key to ending the cold war, permitting the reunification of Germany, the consolidation of the EU and drawing our two nations together in a historic cooperation.

Farewell, indeed, Baroness Thatcher. We Americans will not see you again in our time, but we will never forget you.

Hadley Freeman

"Thatcher is one of the clearest examples of the fact that a successful woman doesn't always mean a step forward for women"

She was, of course, the first and so far only female British prime minister, Jon Snow reiterated on Monday night, insinuating that this achievement should in general be celebrated, never mind the specifics of her leadership.

"Yes and that was one of the many weird things about her," smirked Alexei Sayle. In the pantheon of this comedian's attacks on Thatcher, it was a retort that probably won't be treasured longer than the best lines from The Young Ones.

This was hardly the first or even the worst example of a dig at Thatcher tinged so needlessly with sexism. Of all the things to criticise Thatcher for, calling her out for being a woman seems like something of a wasted bullet. Yet despite the attempts of some columnists to claim otherwise, Thatcher can't really be seen as "a warrior in the sex war", let alone as "the ultimate women's libber". Far from "smashing the glass ceiling", she was the aberration, the one who got through and then pulled the ladder up right after her. On the same edition of Channel 4 News, Louise Mensch named only three successful female politicians as part of her defence of Thatcher – and only one of those was a Conservative.

In truth, Thatcher is one of the clearest examples of the fact that a successful woman doesn't always mean a step forward for women. In 11 years, Thatcher promoted only one woman to her cabinet, preferring instead to elevate men whom Spitting Image memorably and, in certain instances, accurately, described as "vegetables". You may not be a fan of Edwina Currie but, really, was she any worse than John Gummer? "You would see MPs who came into any politics after I had and who were no better than me being promoted over my head," said Currie this week. "She had been offered the chance to get on and effectively she then refused to offer it to other people."

As Matthew Parris evocatively put it in Monday's Times, "She rather liked men (preferring our company, perhaps, to that of women), [but] she thought us the weaker sex."

This attitude – that men are fun but dumb, women are smart but strident, a view of the sexes that seems to come straight out of a Judd Apatow film – led to various quotes of hers that some like to twist into proof that Thatcher was an unwitting feminist. These include, "We have to show them that we're better than they are", and "Women can get into corners that men can't reach!" But really, such statements were anything but, first because sweeping statements about genders are the opposite of gender equality and second because they revealed her real attitude towards women, which lay behind her notable lack of female-friendly policies, her utter lack of interest in childcare provision or positive action. (They also reveal how she loved to surround herself with yes men who were always men.) Rather, she was a classic example of a certain kind of conservative woman who believed that all women should pull themselves up just as she had done, conveniently overlooking that not all women are blessed with the privileges that had been available to her, such as a wealthy and supportive husband and domestic help. (Interestingly, Currie also recalled that when she approached Thatcher in 1988 to get approval for the world's first national breast-screening programme, she tried to appeal to the PM initially "as a woman" but that swiftly proved unsuccessful. So instead: "I put it to her that we would be saving money." That did the trick.)

Women aren't always good for other women because the gender of a person matters a lot less than that person's actual beliefs. I am reminded of this every time the debate comes up about whether more female bylines would reduce sexism in the media. Yet the Daily Mail has more female bylines than any other UK paper and is not exactly a totem of gender equality and female-friendliness.

Contrary to an increasingly common belief, "a woman who is successful" is not synonymous with "a feminist". On the day Thatcher died, the Daily Mail ran a piece claiming that Coco Chanel "was a feminist before the word existed". Leaving aside the detail that the word "feminist" came into existence in 1895, comfortably in Chanel's lifetime, the woman who valued femininity above all other qualities in a woman and was heavily involved with the Nazis, including a wartime relationship with German officer Hans Gunther von Dincklage, could not, in any circumstances, be described as a feminist.

And nor could Thatcher, much to her relief as she allegedly abhorred the word, as doubtless Chanel did, too. Both were successful women who could play the flirt card when it suited them, but ultimately had little interest in being kind to their own sex; Thatcher especially resented being defined by her gender. People should pay her the respect of doing the same after her death. She wasn't a feminist icon and she wasn't an icon for women. Any attempts at revisionism do no favours to her, women or feminism. To claim that any woman's success is a boon for feminism is like saying all publicity is good publicity. Seeing as women aren't a minor Brit-flick grateful for even a bad review, that truism doesn't quite hold true here. She was a prime minister who happened to be a woman. It's how she would have, if pressed, put it herself.

Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett

"The widening of income differences between rich and poor that took place during the 80s is the most rapid ever recorded"

Margaret Thatcher's most important long-term legacy is likely to be the huge rise in inequality that she caused. The widening of income differences between rich and poor that took place during the 80s (particularly from 1985) is the most rapid ever recorded. The most widely used measure of income differences shows inequality increasing by more than a third during her period in office.

The proportion of children living in relative poverty more than doubled during the 80s, and the damage has never been undone. Many of the effects of inequality have long lag periods. As Danny Dorling says in his 2004 study of the rise in violence: "Those who perpetrated the social violence that was done to the lives of young men starting some 20 years ago [the mid-80s] are the prime suspects for most of the murders in Britain." The young men were those whose childhood was blighted by the effects of relative poverty and inequality on family life.

Thatcher is often credited with showing that you could get to the top whatever your background. But as weand others (including Alan Krueger, chair of Obama's council of economic advisers) have shown, wider income differences reduce social mobility and make it harder for people with poorer backgrounds to do so. Now she would more likely have been beaten to the Tory leadership by one of the Etonians in cabinet. Although the "right to buy" and the privatisation of utilities by selling shares to new small investors was often justified as giving rights to "the little people", the reality is that the less well-off fell ever further behind the rich.

Though she recognised the dangers of global warming, Thatcher's industrial and economic policies prioritised economic growth. But growth rates in the decades since her period in office have been lower than during those that preceded her; nor does the balance of research evidence suggest that greater inequality acts as a spur to growth. Understandably, less cohesive societies – with more drugs, more crime and lower mobility – waste talent, and are not good places to do business.

Weakening the power of trade unions was not only essential to her project, but several studies suggest that their continued weakness may be an important part of the reason why inequality has not declined in the intervening decades. International studies of OECD countries suggest a close relationship between the decline in trade union membership and the rise in inequality. From a peak of 13 million in 1979, trade union membership had declined by 30% by 1990, and is now not much more than half what it was. In a world where most media talking heads come from the top few percent of income earners, unions are not only important in wage bargaining, they also provide some of the few well-informed voices whose job it is to speak on behalf of the less well-paid. That bonuses and top incomes continue to rise while the incomes of the rest of the population struggle to keep up with inflation tells us that what we needed was legislation to ensure employee representation on company boards and remuneration committees as many of our European partners have.

The price we all continue to pay for Thatcherite policies is to live in a less cohesive and more antisocial society, in which community life is weaker, people feel less able to trust each other and fewer of those in government have the experience and compassion to represent or understand the vast majority.

Thatcher's infamous failure to recognise the existence of society was a double failure. A growing body of research now shows that the quality of social relations is among the most powerful influences on the happiness, health and wellbeing of populations in the rich countries. After material needs have been met, research has repeatedly shown that further rises in material standards contribute less and less to wellbeing. In rich societies such as the UK, what makes most difference to the real quality of our lives is the quality of community life and social interaction.

Statistics now confirm what many people have always recognised: that inequality is divisive and socially corrosive. The evidence shows that greater equality provides the foundation on which higher standards of social wellbeing can be built.

As a result, Labour authorities in eight or so British cities have set up fairness commissions to reduce income differences locally. By raising the pay of their own staff to a minimum of the living wage, they have set an example which a growing number of large private-sector employers have followed. As working families in poverty now account for more than half of those below the poverty line, a government committed to "making work pay" should surely encourage this trend and raise the minimum wage. The news last week that they are instead considering cutting or freezing the minimum wage surely undermines any pretence that the government is acting either coherently or in the public interest.

Charles Kennedy

"Thatcher was convinced that she understood the Scots – yet couldn’t understand why we remained so stubbornly resistant towards the notion of understanding her"

When I started knocking on Highland doors in May 1983, two things struck me more than any other. First was the sheer depth of hostility towards the Tories in general. Second was the particular hostility towards Margaret Thatcher and her local ministerial spear-carrier, energy minister and incumbent MP of 13 years' standing, Hamish Gray. People would denounce them unequivocally, often in graphic terms. More than once the view was advanced that it was a pity the IRA had not succeeded in their ultimate objective when they bombed the Grand Hotel in Brighton. This is not the Highland way.

And then, perversely, would come the throwaway, sign-off remark – to the effect of: "At least you know where you stand with Maggie – she hates us and we hate her."

Therein, 30 years ago, lay the great Thatcher asset – and the electorally lethal Thatcher impact in Scotland. A strong, so strong, leader. Sharp definition, hard edges, no effort at fuzzy contours (David Cameron, take note). Yet a leader that a wide cross-section of Scots had come to despise. As I spread my wings in politics, I discovered many Thatcher voters down south who were the same kind of people who loathed her in Scotland. They were puzzled by the Scots' antipathy, given the Falklands war and the strong militaristic history of the Highlands and elsewhere.

Like John Major in her wake, Thatcher was convinced that she understood the Scots – yet couldn't understand why we remained so stubbornly resistant towards the notion of understanding her. But we reckoned we got Thatcher only too well and didn't like what we saw, far less what we heard.

That 1983 general election contained the telltale seeds of eventual Scottish Tory self-destruction. The Tories triumphed, of course, and lost only two sitting MPs – Hamish Gray and the social-security scrounger-bashing Iain Sproat, who vacated his marginal Aberdeen seat and headed for the Scottish Borders, only to suffer defeat there at the hands of the Alliance. By 1987, anti-Tory tactical voting had taken hold. A decade later they were wiped out in terms of Scotland-based Westminster constituency representation. Scottish – and by extension UK – politics has been skewed ever since.

If the Falklands war was the making of Thatcher, then the poll tax was her achilles heel – not least in Scotland. That, plus (inevitable) de-industrialisation, coupled to her perceived overbearing and patronising manner. We were not unique in such a response but she failed to appreciate that Scots are balanced, canny folk – insofar as we have a well-developed chip on each shoulder. Scotland was her mission impossible.

In the current wall-to-wall media welter, I caught the current leader of the Scottish Tories, Ruth Davison MSP, being asked if Thatcher was an electoral asset for her. She pointed out that she was only 10 years old when she ceased to be prime minister. Certainly, in 1983, it did not occur to me to criticise Harold Macmillan or Alec Douglas-Home on the doorstep as a sure-fire vote turner.

The fact that the Thatcher question even gets asked confirms vividly just what an upas tree she remains for Scottish Toryism.

Gerry Adams

"Her government's policies handed draconian military powers over to the securocrats, and subverted basic human rights"

Margaret Thatcher was a hugely divisive figure in British politics. And for the people of Ireland, and especially the north, the Thatcher years were among some of the worst of the conflict. Her policy decisions entrenched sectarian divisions, handed draconian military powers over to the securocrats, and subverted basic human rights.

Thatcher refused to recognise the right of citizens to vote for representatives of their choice. She famously changed the law after Bobby Sands was elected in Fermanagh and South Tyrone. And when I and several other Sinn Féin leaders were elected to the Assembly in 1982 we were barred from entry to Britain.

Margaret Thatcher's government defended structured political and religious discrimination and political vetting in the north, legislated for political censorship and institutionalised, to a greater extent than ever before, collusion between British state forces and unionist death squads.

It was under her leadership that in 1982 that the Force Research Unit (FRU) was established within the British Army Intelligence Corps. This unit recruited agents who were then used to kill citizens. Among them was loyalist Brian Nelson, a former British soldier and member of the Ulster Defence Association.