An original Black Panther departs, having bridged San Diego’s eras of racial struggle

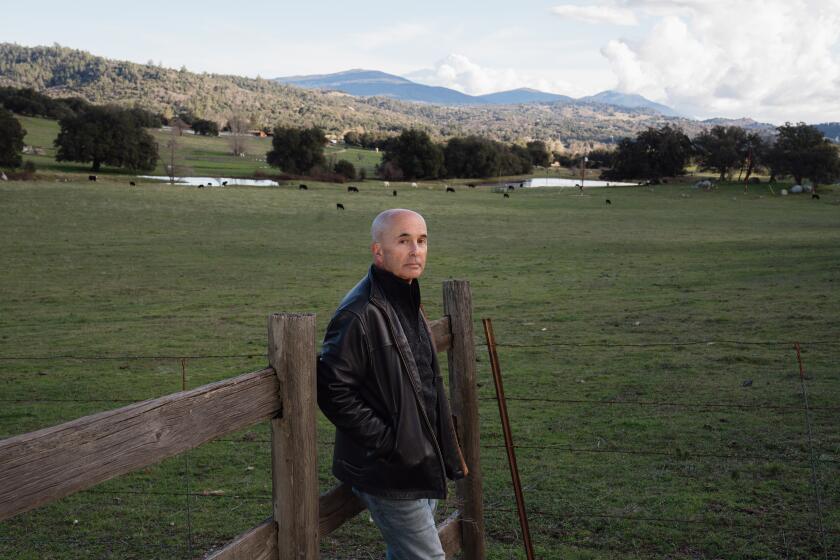

Trunnell Price, who died Jan. 26, was remembered for mentoring a crop of young activists who carry on the Panthers’ legacy

The somber procession of ashes was led by a new generation of the Black Panther Party movement, a final farewell fit for a Panther from a different era.

In black berets, they raised clenched fists in the air, saluting the velvet-encased urn topped with a matching beret.

Trunnell Levett Price was among the last of San Diego’s original Black Panthers. He was memorialized Saturday not only for the fight he embarked on some 50 years earlier, but for mentoring a crop of young activists who are carrying on the iconic movement’s legacy today.

Price died Jan. 26 at the age of 71 after a long battle with lung disease.

He was proud of his place in history as part of a complicated movement that often suffers from oversimplification in its retelling.

The Black power movement — marked in pop-culture by its militant edge and Marxist-tinged philosophy — called for self-defense against police abuse and the uplifting of marginalized communities. It defined his life in many ways.

“He was very concerned for the community, for poor people in general, especially Black people,” Pastor Buddy Hauser, who served in the Panthers with Price as a youth, told mourners at the Spring Valley memorial service. “He stood for us when a lot of people weren’t even thinking about us.”

Price rode waves of vilification and lionization as a member beginning at the age of 17, finding a sense of purpose for providing for Black people what White society wouldn’t, while at times facing the consequences of crossing lines to accomplish that goal. Like many Panthers of the era, he also bounced in and out of the criminal justice system.

His death comes at a time of renewed public interest in the Panthers. In 2016, the party celebrated its 50th anniversary and sparked an urgency to preserve the histories of original members. Two recently released films — “Judas and The Messiah,” a biopic of Panther leader Fred Hampton showing on HBO Max, and Netflix’s “The Trial of the Chicago 7” — offer Hollywood-style retrospectives of the extremes government went to to neutralize the movement.

Even late in life, Price saw a roadmap in the Panther ideology that he believed could be used to fight today’s social and racial injustices. He helped reactivate the movement with a new group, the Black Panther Party of San Diego, which puts the original tenant of community service into practice with programs that include homeless outreach, food assistance and resume-writing classes.

“I’m really excited about this generation coming up,” Price said in 2017 in an oral history recorded at San Diego State University. “They’re the ones who are going to decide whether we continue to suffer for the next 10 or 15 years ... to do what it is that’s in their hearts. They know the difference between right and wrong.

“I give them 20 years. That’s a lot. A lot can happen in 20 years.”

Recruited

The fourth of nine children, Price was born in Coronado, where his father worked for the Navy. The family lived in modest housing for blue-collar military workers.

As a child, he learned about systemic and institutionalized racism by seeing White landlords demand sex for rent from women of color, he said in an interview with The Activated Podcast last summer.

His family later moved to Stockton, one of several southeastern San Diego neighborhoods settled in the 1950s and ‘60s by Black residents who faced worse housing discrimination in other parts of the city.

There, police abuse was rampant, according to residents. From humiliating traffic stops to beatings at a downtown lumberyard, Black youth have recalled how officers doled out their own version of justice to exert dominance and extract street intelligence.

“They were sending a signal to the neighborhood: They were in control,” Henry Lee Wallace, who served in the Black Panther Party as a teen with Price, recalled of the police. “They were the slave masters and they were keeping us in line.”

It was 1967 when Price heard that the founding chapter of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, born a year earlier in Oakland, was going to be in San Diego. Local universities and colleges had been resisting some Black students trying to enroll, and the Panthers wanted to advocate for greater access to higher education.

Price attended the Panther protest on the campus of San Diego State College, meeting party co-founder Bobby Seale and leader David Hilliard.

“I was convinced that their program, which included education, was something I thought I could get involved with and would help uplift oppressed people and people of color,” Price said in his interview with SDSU.

Price was soon recruited into the newly formed San Diego chapter of the Panthers by its first chairman, SDSU student Kenny Denmon. He died in 2018 at the age of 78.

The young Price was intent on soaking up the lessons the Panthers had to offer — everything from Black history to the 10-Point Plan that defined the party’s agenda to social capitalist ideology.

“The education the Black Panthers offered to young recruits was different from the education we were getting at school,” said Wallace, who was also brought into the party by Denmon, his brother-in-law. “All we saw was George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. We didn’t see anything representing Blacks in history books.”

Price was soon given the role of deputy minister of education and was put in charge of running classes for members, teaching social and economic survival.

“He was very studious, he didn’t show the militancy part of it,” Wallace said.

But as Price later recalled in interviews, the party’s focus on self-defense from abusive police was also a major draw for him.

Wearing the group’s signature leather jackets, members openly carried guns, which was legal at the time, and saw themselves as protectors of their community. They often patrolled neighborhood streets for police activity, stopping nearby with their weapons visible to monitor for civil rights abuses.

Their interactions with police were guided by one rule: “We won’t instigate anything, but we will certainly defend ourselves,” Price said in an interview.

The anti-police stance took on more radical undertones, with cartoons in the national Panther Party newspaper that depicted officers as pigs — including one that read: “The only good pig is a dead pig” — fueling the party’s image as violent and criminal. A former party newspaper editor later testified before Congress that the cartoon was political satire.

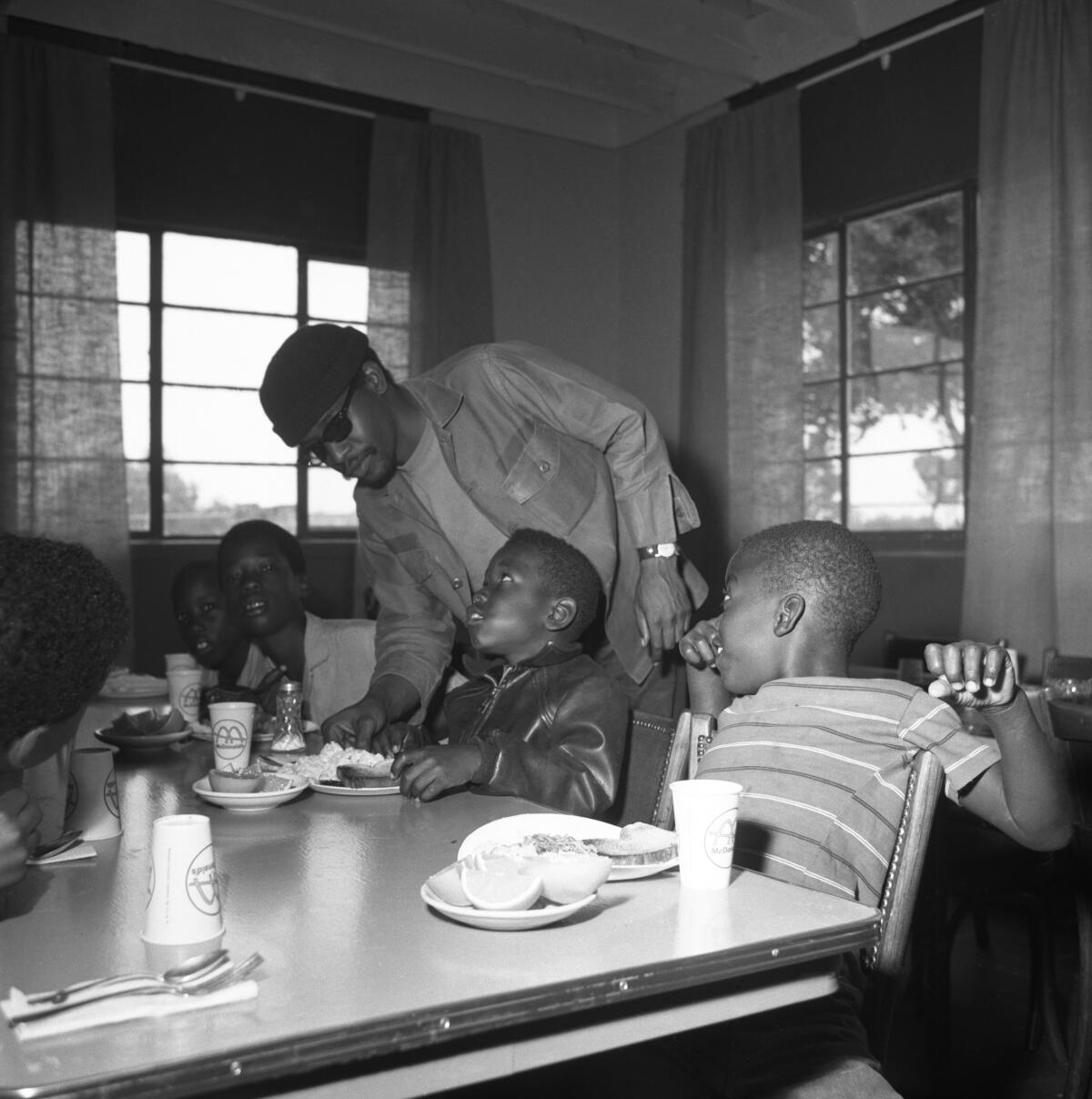

The militant persona was softened with a number of social programs the Black Panthers brought into communities, from food and clothing distributions to medical clinics to providing children regular free breakfasts before school.

In San Diego, the breakfast program operated out of Christ the King church, then a small Catholic parish just blocks from Price’s family home.

The specter of armed Black revolutionaries put the Panthers in the crosshairs of J. Edgar Hoover, the longtime FBI director who used the agency’s clout to investigate and intimidate those he viewed as politically radical. But it was the breakfast program that he viewed as especially dangerous. He saw the goodwill the Panthers were eliciting from the community as a tool of indoctrination.

In 1969, Hoover declared to Congress, “the Black Panther Party, without question, represents the greatest threat to internal security of the country.”

A threat to neutralize

The FBI’s weapon of choice against the Black Panthers was COINTELPRO, a counter-intelligence program that had already been in use for several years against other groups. The goal, according to FBI records later made public, was to neutralize Black militant groups to prevent the rise of a messiah-type leader, to “pinpoint potential troublemakers and neutralize them before they exercise their potential for violence” and to widely discredit the movement.

To do that, the FBI infiltrated the party, sowed distrust among its members and used local police to harass and arrest members. The FBI also instigated deadly rivalries with Organization US, another Black nationalist militant group, by planting fake threats and insults. The disinformation sparked tit-for-tat violence in San Diego, with two Panthers dying in shootings in 1969.

The agency hoped the Panthers would rip themselves apart.

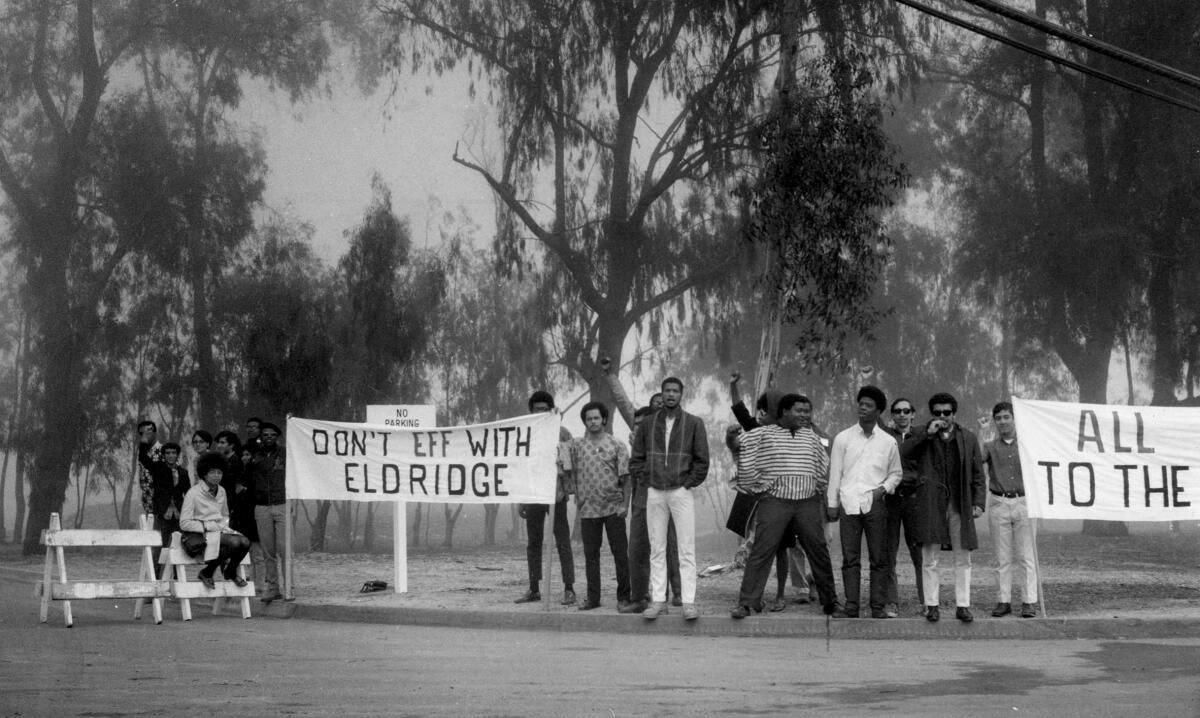

Price was at the forefront of that war as member of the Vanguard, the unit assigned to protect Panther leadership and sniff out opposition throughout the state.

In an interview with The Activated Podcast, he described one Thanksgiving night in San Francisco being on bodyguard duty for Eldridge Cleaver, the party spokesman who had skipped bail and was wanted by law enforcement for provoking an ambush that wounded two Oakland police officers.

On Saturday, friends from the old neighborhood recalled “the greatest escape,” when law enforcement in San Diego tracked Price to a friend’s home and he walked away under their noses disguised as a woman.

Fallout

Jail was a familiar place to most Panthers, whether the charges were legitimate, cooked-up, or both. Price was no exception.

In 1969 he was charged in a sniping incident in which a bullet fired at a San Diego police car narrowly missed two officers inside, according to reports in the San Diego Union. The charges apparently didn’t stick. Wallace recalled the incident and said Price had possibly been with the shooter in a case of being at the wrong place at the wrong time.

In 1971, Price was convicted by an all-White federal jury for being the getaway driver in an armed robbery of the downtown postal office. Price testified that the men had flagged him down randomly for a ride and that he didn’t know they had robbed the office.

Price made headlines for his theatrics during the trial and sentencing hearing, including trying to leave the courtroom at one point while still in the custody of U.S. Marshals Service and later proclaiming: “I’m not an American citizen. I’m a slave. My slave name is Trunnell Price. We are the revolutionaries and you will have your day in court.”

Price’s 25-year sentence was later reduced to 15 years after a federal appeals court found issues with the trial. At the resentencing hearing, Price’s mother, attorney and minister argued that he’d reformed during his time at the Leavenworth penitentiary in Kansas.

Price was apparently released early, although he would rack up other federal and state charges over the years, including a six-month stint in federal prison for misdemeanor drug possession in 1979.

The Black Panther Party officially dissolved in 1982, although it had lost much of its influence long before that.

Its original members were left disillusioned with signs of post-traumatic stress disorder and criminal records as they saw the status quo return in many ways, said Renee Walton, who came to know Price as a member of the revitalized party. “They were left feeling, like, ‘What was that all about?’”

The era was populated with its share of White left-wing radicals, too, many of whom went to prison. But many of those adherents were able to shed the stigma and offered the resources to move forward, unlike their Black counterparts.

“We got jailed, shot, beat up, and now I have a criminal record,” Walton said, putting voice to the Panthers’ angst. “What about employment?”

A lot of members turned to drugs and alcohol, which resulted in more arrests.

“There’s a lot of glory associated with the party, but you know, what those guys went through,” Walton said. “Their accomplishments were huge, but they didn’t feel like it. They ended up not really with anything tangible.”

A new chapter

The Black Panther Party has since been recognized as one of the more influential — albeit controversial — political and civil rights movements in modern history, helping to lay a foundation for today’s Black Lives Matter movement.

In 2016, Alfred Olongo, a Black man suffering from a psychiatric episode, was fatally shot by an El Cajon police officer after he pointed a device at the officer that turned out to be a vaping pen. The shooting opened familiar wounds in the community and thrust San Diego once again into the national debate over use of force.

That same year, some of San Diego’s original members — including Price, Wallace and Hauser — reconnected to share their oral histories.

They had the attention of a new generation of activists who saw an opportunity to build on the Panther legacy.

The Black Panther Party of San Diego was born. Price, who had gone on to have a career in transportation and construction, easily slipped back into his role as educator and historian, along with a new one: mentor.

Price served as chairman of the new group for a few years until his lung condition worsened in 2018.

“He taught that youth need to make sure they are more than just protesting, that they are completely educating themselves on the political process,” said current chairman Robert War Williams. “It’s not about the protest lifestyle, it’s about the lifestyle of empowerment.”

The group’s 10-Point Program closely follows the original, but is updated for the current times. It still demands equal access to “land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace.”

The literal paramilitary image of the ‘60s has also been swapped for a more figurative paramilitary-like discipline necessary to defend a cause.

“You’re not going to see us carrying AK-47s and marching. We don’t agree with that,” Walton said. “Our approach today is trying to reach people and encourage and empower them.”

The group is among several autonomous organizations flying the Panther banner around the country; an official national umbrella no longer exists. Wallace reactivated his own version, the San Diego Original Black Panther Party for Community Empowerment, a nonprofit focused on distribution and education programs. The Panther name also has also been used by at least one group to espouse racist and anti-Semitic views, which are denounced by both original and modern Panthers, including those in San Diego.

“The Black Panthers of the ‘60s are what the ‘60s needed,” Walton said. “We are the Black Panthers of 2020, and we want to be what’s needed now, or at least be part of it.”

Price is survived by mother, Ruby Vryes-Price; wife, Michele Geiger; son, Leonard Price; and stepdaughter, Nicole Ventura, as well as two grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.