You don’t have to watch Croatia for very long to come up with a pretty good guess as to which of its players kissed a photographer 10 minutes before the end of extra time during a World Cup semifinal.

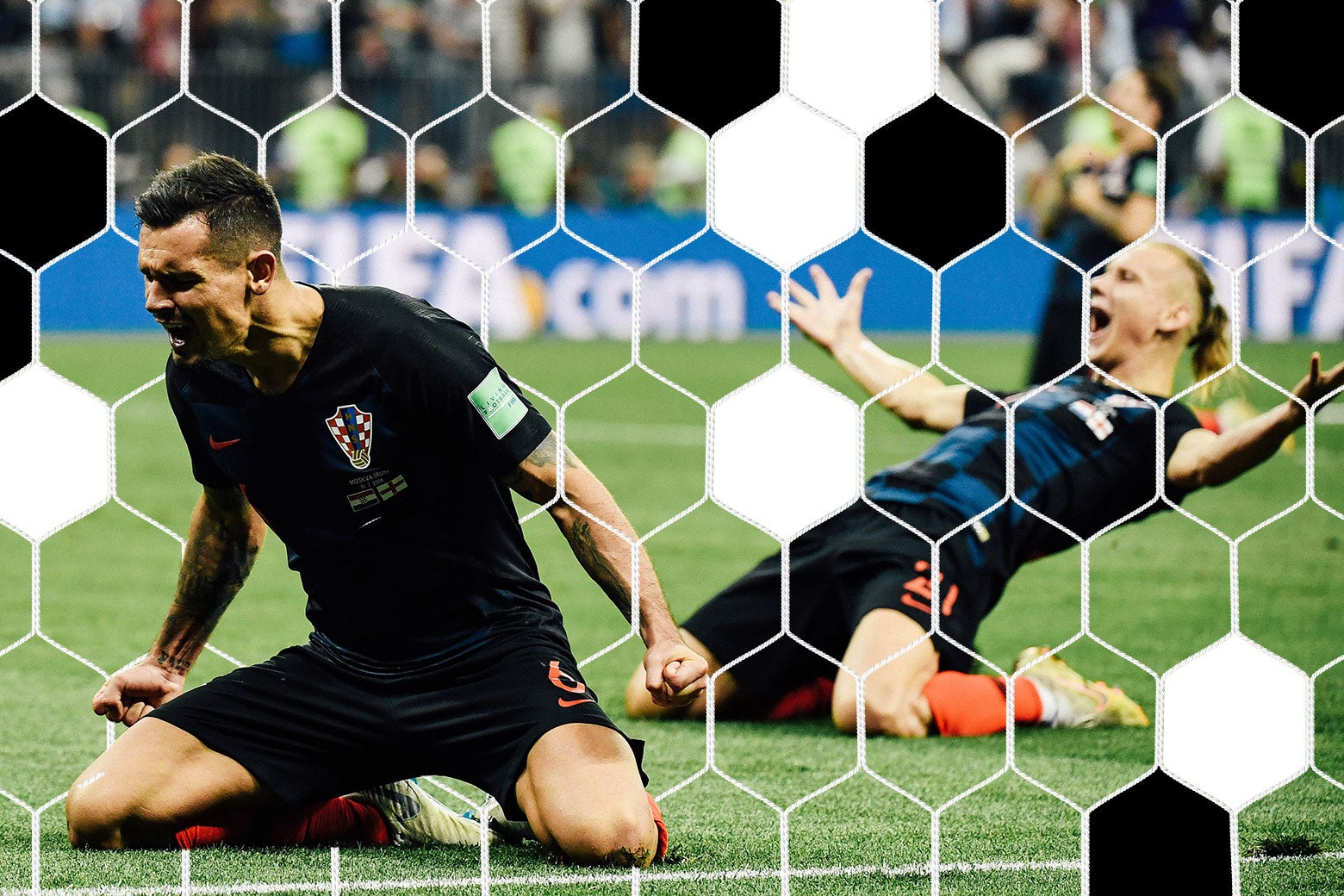

It was one of the most affirming, most human stories to come out of one of the world’s premier generators of affirming human stories: Mario Mandzukic, scorer of the extra-time goal to give Croatia its 2–1 lead over England, runs to the sideline to celebrate in front of the crowd. He’s mobbed by his teammates, and the combined force of their arrival drives him into a scrum of photographers, where he and some of the substitutes land more or less on top of AFP photographer Yuri Cortez.

Cortez, being a consummate professional, kept shooting. The particular combination of jubilation and concern and disbelief written across Mandzukic’s face makes the moment feel incredibly intimate, perhaps because it’s roughly the same blend you’d get watching someone hold his child for the first time.

It was as if, just for a minute, the real world intruded upon the hermetically sealed environment of a global sporting contest, disproving all the coach-speak clichés about how the only thing that matters is what happens within the four lines of the big green rectangle. It was beautiful. The Croatian players pulled Cortez to his feet. Ivan Rakitic checked to make sure he was fine. And center back Domagoj Vida, all cheekbone and blond ponytail, practically wrung Cortez’s neck as he turned the photographer back toward himself so he could plant a big wet one right on Cortez’s forehead.

On a squad full of guys that play with their emotions on their sleeves and chips on their shoulders, Vida wears the biggest, shiniest epaulettes of all. His angular face seems stretched in a permanent screaming grimace. He looks and plays like a professional wrestler hoping someone selects him for a shot at the title. Vida, Croatia’s anarchic wild card, seems constantly aware that he’s not supposed to be here but is determined to stay on the ride for as long it goes.

Vida nearly missed the semifinal when a pair of videos surfaced of him in the locker room after Croatia’s quarterfinal win against Russia. In those videos, he could be heard saying both “Belgrade burn” and “Glory to Ukraine,” the latter a phrase associated with groups fighting Russian-backed separatists in Eastern Ukraine that, per the BBC, “has become strongly associated with critics of the Kremlin’s policy.” FIFA is typically so “stick to sports” that it can make the NFL look like the ACLU, but it decided against a ban in this case, possibly because the stakes were so high.

Vida, like many people about to get in trouble for something they’ve said, claimed it was a joke, but he likely hadn’t picked up the phrase in passing. He spent five years of his career at Dynamo Kyiv in Ukraine, moving there in 2013, a year before the annexation of Crimea. He moved this January to the Turkish power Besiktas, where he was red-carded 16 minutes into his first Champions League match with the club.

Which is another reason why Vida knows he’s lucky to be here. His opposite numbers in the French defense Sunday will be Raphaël Varane and Samuel Umtiti, who play for Real Madrid and Barcelona. Vida wasn’t even necessarily going to start at center back during the World Cup; veteran Vedran Corluka got the nod in the middle next to Dejan Lovren in each of Croatia’s two warm-up friendlies.

Lovren is hardly a sure thing either. Though he plays at a higher level than Vida at Liverpool, he has lost his starting spot and won it back multiple times during his four seasons there. He is capable of both match-saving plays and horrible mistakes, sometimes in the same game. Last October, Harry Kane exposed Lovren so badly in a Premier League game the Croatian was substituted after just half an hour. Wednesday’s semifinal, in which Kane failed to score, provided a measure of vindication and led Lovren to claim he’s “one of the best defenders in the world.” The world begs to differ. Truth is Lovren was kind of lucky to make it to the end of the England game, as he could very well have been booked for more than one of the fouls he committed.

Lovren too has courted controversy with his postgame celebrations. A clip was posted after Croatia’s win over Argentina of him singing “Bojna Cavoglave” in the locker room, an anti-Serb song featuring a chant favored by World War II–era Croatia’s pro-Nazi movement—a chant that’s now being adopted by some on Croatia’s present far right. While Lovren’s video didn’t feature the part of the song that includes that chant, in 2013 defender Josip Simunic was given a 10-game international ban for celebrating Croatia’s qualification for the World Cup by leading fans in the chant.

Soccer and politics have been intersecting in Croatia since its fight for independence from Yugoslavia. As we’ve already seen at this World Cup, the Balkan conflict and its enmities still reverberate into the present day. Switzerland’s Granit Xhaka and Xherdan Shaqiri, both of Kosovar Albanian descent, were fined for making hand gestures associated with Albanian nationalists after they scored against Serbia in the group stage. Croatia has been good at soccer since it became an independent nation—it made the semifinals of the first World Cup it could enter, in 1998, losing to France in the semifinals—and as such it has been a popular vehicle for groups seeking to project strength. And, like many other places, that embrace of sport by political elements has not always been pretty.

Croatia’s next game against England, its first home game in the new UEFA Nations League, will be played in an empty stadium as part of a punishment it received for an apparent swastika scuffed into the field during a qualifier against Italy for the 2016 European Championships. That game was also being played behind closed doors due to a stadium ban received for fans’ racist chanting.

Trying to untangle the dense web of historical, cultural, and sociopolitical threads that intertwine in the Croatian team and its supporters is impossible. Which parts of their shared backgrounds gave the Croatian players the mental fortitude to bury their penalties against Denmark and Russia, and which led to the singing of war songs referencing fascism in the locker room after an earlier win? Even as we condemn those war songs, it must be said that much of Croatia’s underdog appeal stems from how its players have overcome the disruption of war. Luka Modric famously practiced in the parking lot of the hotel he and his family lived in after they were forced out of their home. Lovren and his family fled the war in present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina, moving to Germany when Lovren was 3 years old.

So, which Vida is more representative: the one so overflowing with joy and weirdness that he kissed Cortez on the head during a game, or the one that appended “Belgrade burn” onto that post-Russia victory video? How do you, as a neutral fan, root against a nation of 4 million people that’s less than three decades old and that’s trying to win its first World Cup? How do you root for players and fans who have behaved in ways so morally repugnant, especially when it’s a small group of players and a limited number of fans? These questions are hard. This is why FIFA wants everyone to ignore politics and just focus on the soccer as much as possible on its watch.

If you are worried about the idea of these guys celebrating with a World Cup on Sunday, you can take solace in the fact that France is favored. On paper, Vida and Lovren do not have the résumés of a World Cup–winning defense, but so far they’ve done just enough to avoid costing their team. They’re not the only underdog central-defense pairing to make it this far. The Netherlands got to the final in 2010 starting the unheralded John Heitinga and Joris Mathijsen, who got by in large part because they had the limitless energy of Dirk Kuyt, the dastardly wiles of Mark van Bommel, and the kung fu stylings of Nigel de Jong protecting them in midfield.

Like that Dutch squad, Croatia has played good team defense rather than asking Vida and Lovren to sort it out themselves. Midfield stars Rakitic and Luka Modric are impressively tenacious given that they’re far better known for their offensive contributions. Winger Ante Rebic is actually leading the tournament in fouls committed per game, which speaks to his commitment to winning the ball back.

The French offense has more firepower than anyone else Croatia has faced thus far, even if French coach Didier Deschamps sometimes seems reluctant to use it. Facing down Kylian Mbappé, Antoine Griezmann, and Paul Pogba will require Vida and Lovren to keep their unfiltered emotions in check for the duration of the final. We’ll see Sunday whether they can pull it off.