The pre-abortion drugs were kicking in, and the seven women in a light pink waiting room were coaching each other through dizziness and chills.

"It's OK, You've got this," one woman said.

"I'm drowsy," said another, curled up in a comfy chair. About half of them had a blanket and a spot to curl up in at this point before the procedure.

The Houston Chronicle reports Elsa Vizcarra's job that day was to try to interview all of them.

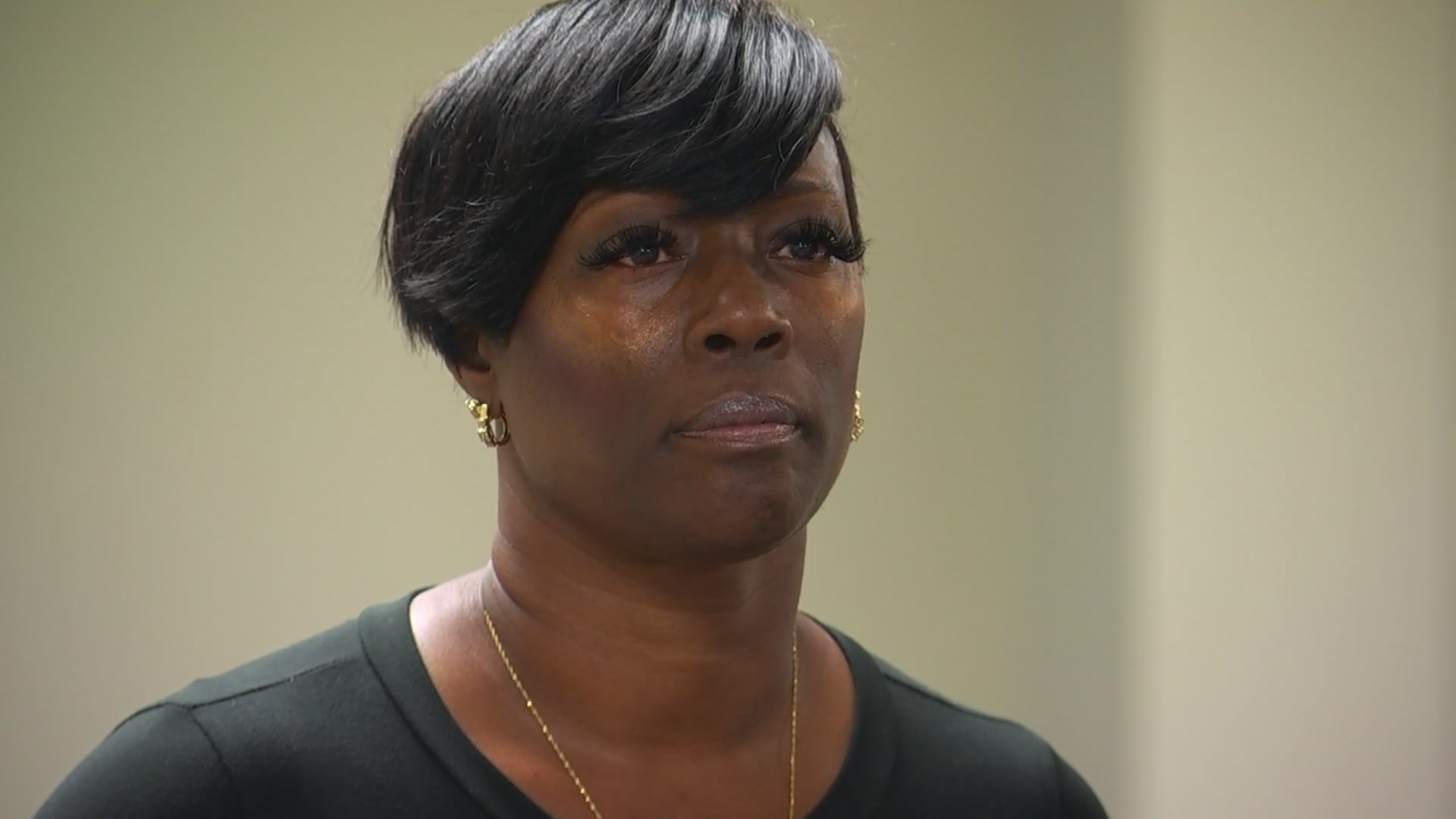

Vizcarra, a University of Texas researcher, spent the better part of a year sitting with nearly 600 abortion patients at a dozen clinics around Texas to understand what led the women to these waiting rooms and what barriers they faced to get there. This story is based on her account of some of those conversations and clinic visits -- Vizcarra and the UT research team she is a part of withheld details on locations of the clinics, and on the women interviewed, to protect their privacy.

Mostly, she was struck by their resilience -- to drive more than 100 miles round trip to their appointments to look at state-mandated ultrasound pictures of the fetus, then to return again 24 hours later for pills or procedures to end their pregnancies. To walk past protesters, some of them belligerent, each time they enter the building, shaming them with Bible verses and rosary beads.

"I don't think most people know what it's like to go into an abortion clinic," said Vizcarra, a study coordinator for the University of Texas at Austin's Population Research Center & Texas Policy Evaluation Project. Now, she knows.

Local

The latest news from around North Texas.

The vast majority of the women Vizcarra spoke with knew about the difficulties they would face, she said, and were willing to share their stories.

"Not one experience is universal," she said. "We're doing this study to find out what's going on, what is the state climate. And I think people are receptive to that."

The Republican-led Legislature has strategically created more than a dozen laws to discourage women who want to end their pregnancies. Texas is one of about a dozen states that require counseling on fetal pain. Other laws require women to wait at least 24 hours after an initial appointment to undergo an abortion, and to receive information about the procedure that doctors say is flawed, and other hurdles in hopes women will change their minds.

While Texas abortion laws are some of the strictest in the nation and have been struck down or blocked in court several times, there is little doubt that the strategy is working: the number of abortions in Texas has plummeted from 81,000 to 54,500 over a decade. About two-thirds of abortion clinics have closed since 2011; now there are 21 in a state with 268,000 square miles.

"We're not only doing research for the sake of it -- we're evaluating policy and how the state regulations and the funding impacts women across Texas," said Vizcarra who is conducting other research about contraceptive access for women two years postpartum. "We're measuring the barriers these regulations put on abortion access."

A previous three-year study found women in Texas traveled an average of 42 miles to their abortion clinic. Of about 300 women the Texas Policy Evaluation Project spoke to, nearly a quarter said it was difficult to get to their appointments and almost a third said the 24-hour waiting period had a "negative effect on their emotional well-being."

The 2014 report also found 92 percent of women were sure of their decision both before and after viewing the ultrasound of the fetus, which lawmakers required in 2011.

Vizcarra, a Katy native, began crisscrossing the state in May in her quest, which took her to 12 different abortion clinics, often in a rental car, in search of 50 women at each location about to undergo an abortion or recovering from one. They had to be between the ages of 18 and 44.

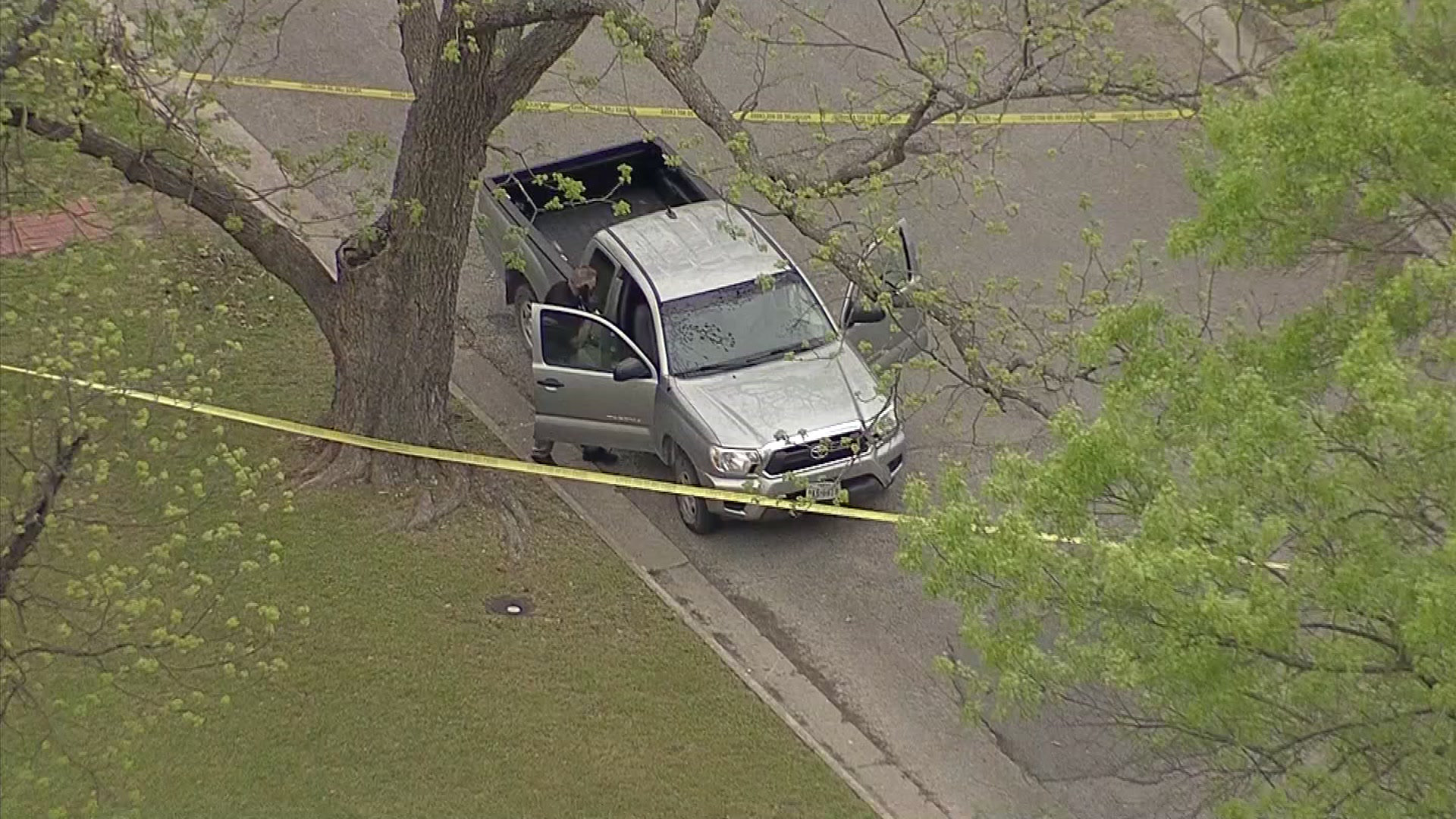

At almost any clinic she visited -- ranging from East Texas to the Rio Grande Valley and including most of the state's major cities -- the day began with protesters, usually two to eight of them, mostly men. Once a group of 10 people stood in front of her car, blocking her from entering the parking lot.

As with any protest, the groups swelled in good weather. Of course, they would assume she was there for an abortion. Usually, they started off nice.

"Ma'am, you don't have to do this."

They insisted that she take a rosary or a religious handout. They would get increasingly more intense as she ignored them.

"Come talk to me."

"You don't know what you're doing."

"They would get more and more belligerent, the more you ignored them," said Vizcarra. She knew she wasn't their target, but "when you have men yelling at you, telling you you're going to go to hell, that's just an additional burden."

While people yelled outside of abortion clinics, the inside is usually as calm as any other doctor's office waiting room: Reruns of The Office or Marvel movies on the TV, patients often accompanied by partners or friends.

"It's not this dark place and everyone's depressed," said Vizcarra. "It takes women so long to go through the process. It's like a really long doctor's appointment."

Vizcarra, with a quiet voice and unjudging brown eyes, would ask them to participate in the study while they waited. When did they know they were pregnant? When did they decide to seek care? Did they try to end their pregnancy on their own? She asked how they found the clinic and how they got there that day, whether they went to a crisis pregnancy center first and how much they were paying for the procedure. What contraception did they use, did they have insurance, what did they know about abortion regulations in the state.

One woman with children took out a payday loan to cover her abortion, Vizcarra said. The woman, who lived in the country, also twice had to pay someone to drive her to the nearest clinic -- once for the initial appointment, the second time for the procedure. If she waited longer, she'd risk needing a surgical procedure with a higher cost.

Another woman was a working professional with insurance who did not realize the state bars both private insurance and Medicaid from covering abortion procedures. That law passed in 2017.

"They know that they're in a time crunch, basically. If they want to take the medication abortion, they have to do it within a time-frame, and they have to have money to do it, and they have to have the transportation, and the time off work, and sometimes they have children," said Vizcarra. "They know what's going on is not helping them."

Anti-abortion advocates say the laws in Texas -- which require providers to furnish women with state-produced pamphlets about the risks of abortion, require parental consent for minors to receive abortions, and boost funding for family planning programs offered by anti-abortion groups -- are necessary to ensure that women have time to consider the alternatives.

"Considering this is an irreversible procedure that will claim the life of an unborn child, one day is more than worth it," said Joe Pojman, executive director at Texas Alliance for Life. "The goal is to make abortion unnecessary in the minds of every woman through practical solutions."

Texas lawmakers want to pass stiffer abortion laws this year. Legislators in the House and Senate are pushing bills that would make it illegal to abort a fetus with an abnormality and outlaw abortions after six weeks gestation, among others. One measure would make abortion a crime punishable by the death penalty -- though a similar law has already been found unconstitutional under the 1973 Roe v Wade decision in federal court.

Bills more likely to become law include one that would cut off government contracts with Planned Parenthood and its affiliate organizations that provide non-abortive services like STD testing, HIV outreach and preventive health care. Another would create new penalties for a physician who fails to care for a baby born after a botched abortion -- although Texas health officials reported no instances of this happening in Texas between 2013 and 2016, the most recent data available.

Vizcarra is still sifting through the data and analyzing the results with co-researchers at the UT Texas Policy Evaluation Project. The results need to be peer-reviewed before the findings can be published. They expect to submit papers for publication later this year, possibly as soon as August.