Six years on and Dry January is more popular than ever, but does quitting booze for a month actually make a difference to your life? Looking at the Dry January website, managed by Alcohol Change UK, you’re left in little doubt: you can lose weight, save money, sleep better and have more energy. There is certainly evidence to support the negative effects of alcohol on all these things, but does that mean Dry January causes these positive effects?

To figure out the true benefits of Dry January, you need to think about what you do when you give up alcohol for a month. For instance, do you start doing other healthy things, like take more exercise or eat healthier food? If you do, then that’s great, but the positive effects you will experience are not solely due to temporarily quitting alcohol.

Despite its popularity, the impact of Dry January on health has not been robustly investigated. The most recent attempt in 2017 did not look at whether people made other healthy lifestyle changes when they gave up booze. But a more significant problem is the number of participants who dropped out. While the study results looked positive, they could be misleading, particularly if those who dropped out did so from feeling worse as a result of quitting drinking.

The research was also sponsored by Public Health England, the same group that endorses the Dry January campaign. An independent evaluation would avoid a perceived conflict of interest.

Inconvenient truth

Rather than viewing Dry January as a threat to their business, the alcohol industry views it as a neat distraction from an inconvenient truth. Although alcohol consumption is declining overall, 4.4% of the population account for more than 30% of all the alcohol sold in the UK. But Dry January is not aimed at high-risk drinkers, as Alcohol Change UK makes clear. It would be potentially life-threatening for people in this group to suddenly stop drinking. They need specialist support to reduce their alcohol intake if they are to avoid harming their health or, worse, dying.

Abrupt alcohol withdrawal can kill. So there is a real danger that these campaigns play well with the alcohol industry as they distract attention from a group of people who are at the greatest risk of dying prematurely due to alcohol. This is not a product image you’d want to draw attention to. In this way, Dry January might cause more harm than good, because it attracts those least at risk of developing problems due to alcohol, while neatly distracting attention from those at the greatest risk. The alcohol industry is adept at influencing policy to protect their business model.

Unfortunately, Public Health England recently faced criticism for its own relationship with the industry. It joined Drinkaware, an organisation funded by the alcohol industry, in an “alcohol-free days” campaign that many experts believed was an ill-judged tie up. The campaign’s message appeared to minimise the risks associated with excessive drinking, based on a self-assessment drinking tool.

Those facing the greatest risks to their health as a result of drinking alcohol get the least in the way of services compared to those with more modest risks from alcohol consumption. Alcohol treatment services continue to be cut, while alcohol-related harm continues to rise. This is a classic example of the inverse care law, which describes a situation where those who most need medical care are least likely to receive it.

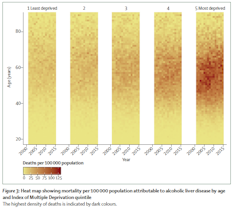

There is a health apartheid as low-risk drinkers are served by campaigns like Dry January and high-risk drinkers are denied support. This is demonstrated by differences in social groups – those from the most socially deprived groups are the most likely to die due to alcoholic liver disease.

Alcohol is a drug that happens to be legally regulated, and like all drugs, there are vested interests that control access to credible information about the health risks. Robust evaluation of the Dry January campaign is overdue. Millions of participants need a more accurate idea of whether or not they should bother (popularity should not be used as a proxy for effectiveness). Money would be better spent on those who need support the most and on tackling the root causes of excessive drinking.