The True History of the South Is Not Being Erased

Taking down Confederate monuments helps confront the past, not obscure it.

Growing up in the 1950s in Richmond, Va., my friends and I would sometimes dig Minié balls—Civil War-era rifle bullets—out of the crumbling remains of Confederate earthworks.

Those earthworks remain, mostly under federal management now—scars in the earth left by a cataclysmic struggle within the American family a century and a half ago.

Growing up in Oregon in the 1990s, my children touched ruts carved in solid rock by the wheels of covered wagons on the Oregon trail—scars in the earth left by a migration that changed history. These scars are endangered, but they are still there too.

History leaves its mark. We can see it if we just look down at our feet.

These musings were sparked by some reactions—some appreciative, others angry—to my article, The Motionless Ghosts That Haunt the South, about the Confederate statuary that dominates the Southern urban skyline: huge, solemn memorials to Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, Jefferson Davis, and other demigods of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy. I wrote that I wish they would come down. “You are trying to erase history,” some of my correspondents said.

Would reducing the bronzed omnipresence of the Confederate General Staff really eliminate “history”?

Let’s look at real history. Americans tend to assume that Southern segregation was a “natural” legacy of antebellum slavery. The truth is far more complicated. After the Civil War, the South went through a period of transition—not simply during “Reconstruction” (which ended in about 1877) but for the two decades that followed. There was no overall “system” of separation; gross racism and discrimination existed alongside tentative inter-racial cooperation and political coalition-building. Until the first decade of the twentieth century, black Southerners continued to vote, to serve on juries, and to hold state and local office. The last “first-generation” black member of the U.S. House left office in 1901.

Only with the rise of the U.S. as an imperial power—forcibly dominating people of color from San Juan to Manila—did the idea of legal white supremacy become acceptable to a majority of whites in North or South. Thus began the era of segregation—a system that subordinated black Southerners economically, disfranchised them politically, and isolated them in public and private space. What’s called the “nadir” of race relations was the early 20th Century, not the 1870s and 80s.

The year 1890 saw the first segregation-era Southern state constitution, in South Carolina, strip blacks of the right to vote. That same year, the giant Lee statue went up in Richmond. Virginia itself disfranchised black voters in 1902. The monuments to Jefferson Davis and Jeb Stuart went up in 1907; the horseback statue of Jackson was unveiled in 1919. All across the South during these years, these statues went up to mark the triumph of the once-outlandish idea of segregation.

Segregation had an official myth: The white South would have freed its slaves voluntarily if not for Northern meddling. The North destroyed the South because it coveted its natural resources and its cheap labor. After the War, corrupt “carpetbaggers” and vile Southern white “scalawags” seized power with Northern bayonets, upheld by ignorant, illiterate blacks. Heroic white conservatives finally did away with the “corrupt Negro vote,” restored to power the South’s natural leaders, and returned black Southerners to their proper subordinate place.

Blacks played no part in any of Southern history. They had no past, and no future, in white America.

As New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu said in his recent speech, “These statues are not just stone and metal. They are not just innocent remembrances of a benign history. These monuments purposefully celebrate a fictional, sanitized Confederacy; ignoring the death, ignoring the enslavement, and the terror that it actually stood for.”

So, what is to be done? Because I know Richmond, I use it as an example, more extreme than many but not different in kind from most cities across the South. Richmond’s new mayor, Levar M. Stoney, recently said, “I want to be a city that is tolerant, inclusive and embraces its diversity, and those statues without context do not do that.” Stoney has called for “a robust community conversation about it that will involve stakeholders and community groups and residents.”

Stoney is right. Context does matter. And the deliberate lack of context is one of the worst features of Southern civic imagery.

You want context?

Monument Avenue, one of the most beautiful divided urban boulevards in the world, runs eastward from Three Chopt Road to Lombardy Street, where it turns into two-lane Franklin Street, which ends two miles father east at Capitol Square.

So let’s start by looking for real history on this very street. Thomas Jefferson designed the Capitol Building; Governor Patrick Henry laid the cornerstone in 1785. Aaron Burr was tried for treason here, and the Confederate “Congress” met here during the Civil War.

At the Capitol, too, United States Colored Troops, on April 3, 1865, raised the American flag for the first time after the fall of Richmond. Here a biracial constitutional convention in 1867 wrote the first truly democratic constitution Virginia ever had. Here Lawrence Douglas Wilder, the first African American elected governor of any American state, was sworn into office in 1990.

In Capitol Square stands the 1858 equestrian statue of George Washington. At the base of that statue, on April 5, 1865, Abraham Lincoln delivered a speech to an audience of freed slaves. Eyewitnesses relate that the wind blew Confederate $1,000 bonds unheeded around listeners’ feet.

Three blocks west on Franklin St. is the site of the old Thalhimer’s Department Store. Here, on February 22, 1960, 34 black students from Virginia Union University were arrested for seeking service in the store’s two all-white dining areas, setting off a six-month boycott and and an eventual key movement victory.

We’re only three blocks into our trip, and we have found more real history on this one street than is contained in the entire procession of dead “heroes” on Monument Ave.

Within a mile of the Capitol, there’s St. John’s Church, where Patrick Henry made his famous “Give me liberty or give me death!” speech; there’s the Tredegar Iron Works by the James River, where slave laborers were forced to forge weapons used to fight for slavery. (It has been converted into the American Civil War Museum.) Not far away is a historical marker to commemorate John Mitchell, the crusading black editor of The Richmond Planet, and a national historical site honoring Maggie L. Walker, the first African American woman to be president of an American bank. A mile and a half east, there’s Shockoe Hill Cemetery, where Chief Justice John Marshall’s grave lies; not far away—open to tourists—is the townhome he built and lived in, now lovingly restored. Down the street from that is Jefferson Davis’s official residence, now also part of the Civil War museum. In the other direction is Hollywood Cemetery, where you can see the actual graves of Presidents John Tyler and James Monroe, as well as of General George Pickett, of writers James Branch Cabell and Ellen Glasgow, and even of Jefferson Davis. Evergreen Cemetery, a few miles away, teems with graves of famous black Richmonders.

Within 11 miles of Richmond is the Cold Harbor Battlefield, where 2,000 Americans died in two weeks of fighting in 1864. To the south is the Petersburg Battlefield, where battle raged from June 1864 to March 1865. Fifty miles north are the most brutal killing fields of the war—Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, the Wilderness, and Spotsylvania Court House.

No one proposes to “erase” any of this history.

It’s not just the dragon-haunted South. Everywhere I have visited or lived—in Eugene, OR; Albuquerque, NM; St. Louis, MO; Chapel Hill, NC; New Smyrna Beach, FL—history of this sort is right at a visitor’s feet, etched into earth and rock, embodied in churches and homes, and interred in tombs. Monuments like the Lee statue are not there to celebrate this kind of history; they are there to disguise it. Lee’s 14-foot statue, atop its base, reaches 60 feet into the sky, Davis’s features a 67-foot obelisk; their purpose is to draw our eyes away from the real world and into the mythic clouds of the Lost Cause.

In fact, they’re not about the past at all, and they never were.

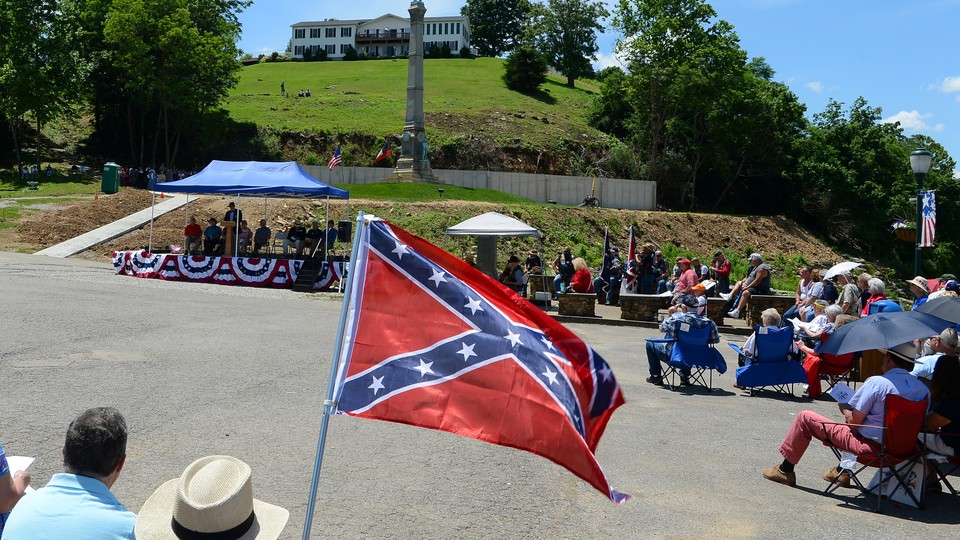

In Charlottesville, Va., last month, a crowd led by white supremacist Richard Spencer carried torches to protest the planned removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee. They weren’t there to honor Lee’s tactical brilliance at the Seven Days’ Battles, or salute the great heart of his warhorse, Traveller. They were there to flaunt their fear and hatred of their non-white neighbors. “What brings us together is that we are white, we are a people, we will not be replaced,” Spencer told the crowd, which chanted in response, “You will not replace us.”

This is not a fight over history; it is a fight over the future. The neo-Confederate faith is not a heritage; it is a political program. And the proper lesson of Southern history is that this radical message—unapologetic, uncompromising, violent white supremacy—lurks in the American bloodstream like a virus, re-emerging at times when the national immune system is weak.

We may be living through an outbreak.

To survive and prosper, the South, and the nation, must renounce this pernicious creed and disarm its symbols. The bronze and marble men do no honor to the region’s true parents; they do, however, dishonor its children.

One way or another, they must yield their unearned pride of place.