The Interminable Body Count

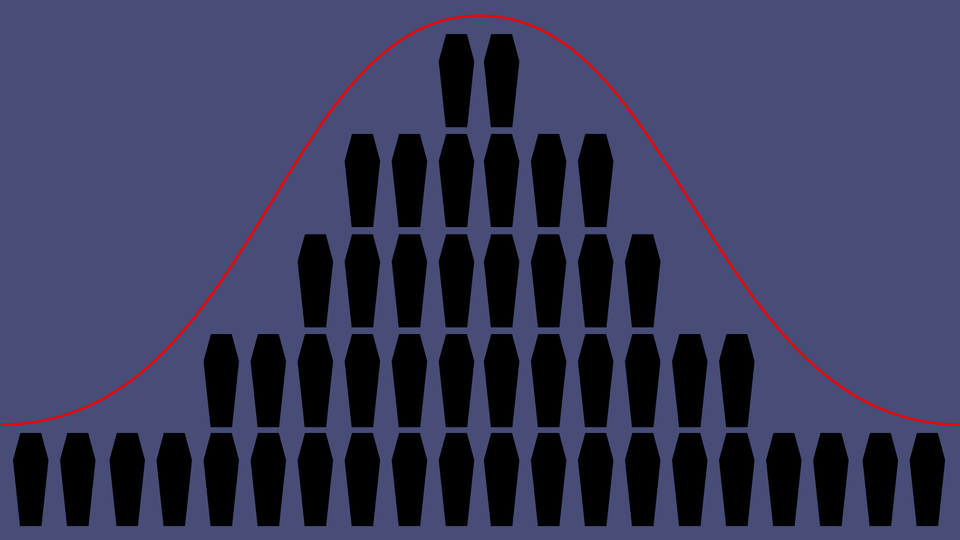

We may never know how many people the coronavirus kills: “It sounds like it could be totally obvious—just count body bags. It’s not obvious at all.”

We rely on numbers to understand the size and scope of tragedy—to gauge what went wrong and put the damage in perspective. More Americans have now died from the coronavirus than were killed in the September 11 terrorist attacks, multiple news outlets announced yesterday.

But we likely won’t have an estimate of how many Americans have died as a result of the pandemic for a very long time—maybe months, maybe a year. We will almost certainly never know the exact number. “It sounds like it could be totally obvious—just count body bags,” John Mutter, an environmental-science professor at Columbia University who studies the role of natural disasters in human well-being, told me in an interview this week. “It’s not obvious at all.”

When Hurricane Maria flattened Puerto Rico in September 2017, the storm’s devastation was overwhelming. Yet the official death toll in December stood at 64 people—a number that almost no one believed, as my colleague Vann Newkirk II wrote at the time. Nearly a year after the storm, a team of researchers tried to develop their own estimate. They gathered months’ worth of mortality data from households across the island and published a study concluding that, in actuality, more than 4,600 deaths were potentially attributable to the hurricane—70 times the official number.

I talked with Mutter, who led an effort to expand the scope of the official death count after Hurricane Katrina, about the trauma the COVID-19 outbreak could cause—and why that trauma is so hard to quantify. Our conversation has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Elaine Godfrey: So right now, we’re hearing that more than 3,000 people have died from the virus in the U.S. The government is estimating that, in the best-case scenario, the total will be somewhere from 100,000 to 200,000 deaths. How confident can we be about those numbers?

John Mutter: The difficulty with estimating fatalities from natural disasters depends on what sort of a disaster it is. Earthquakes are pretty clear, because the typical cause of death is blunt trauma. There’s this old adage that earthquakes don’t kill people, buildings kill people, and it’s pretty true. Your house falls down.

When you die of coronavirus, what do you actually die of? [In some cases] your lungs fill up with fluid, just like it’s pneumonia. So do you die of the virus, or do you die of pneumonia?

This happened a lot in Katrina and with [other] hurricanes: People who already had conditions—heart conditions, respiratory conditions—[their] deaths could result from the exacerbation of those existing conditions. How do you count somebody who died of a heart attack during a natural disaster? Do you call it a disaster death or a heart-attack death? There’s no rules. None. And particularly from country to country.

The [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] here has rules. They’re very conservative; you’ll always get the minimum number from the CDC. And they’re very clear what their criteria are. What you’ll hear about disaster deaths from the CDC is only those that can be absolutely verified as being directly related to that disaster. Then they’ll list all the heart-attack victims. They might call them indirect, but they won’t call them directly related to the disaster. So it’s more of a subtle business than you might think.

In this case, because many people are using emergency rooms and hospitals, it’s crowding out people who would normally be at emergency services. People who have chronic heart conditions, nothing to do with coronavirus, are crowded out of the emergency rooms because there's no space for them. So the death rate will rise with people like that. Do you count them?

Godfrey: The CDC at this point probably wouldn’t count those people, right?

Mutter: They would want to see evidence that the person died because they contracted this virus.

Godfrey: The governor of Puerto Rico said that 64 people died in Hurricane Maria. The Harvard study that came out almost a year later estimated it was something like 4,600.

Mutter: When Trump visited [Puerto Rico], he said the number was 16. And Trump said, Oh, then you’re not having a real disaster. Think about Katrina, where there were hundreds—when in fact there were thousands. He tried to diminish it.

The Economist made an estimate [for Maria], and they thought it was more like 1,000. They were looking at death records [to compare deaths from September 2017 to September 2016]. Every day in September, you get a number that’s pretty consistent. And then you look at it for the day of Maria, and it’s hugely different. This is called all-cause mortality, because it doesn’t determine a particular cause. This is an anomaly above the baseline.

Harvard was interested in that, but they were also interested in the long run. This is always a question with disasters: When do you stop counting? The day after? The day after that? Many people, if they are displaced, particularly the elderly, will die days and weeks afterwards, for many reasons—[it’s] the trauma of displacement.

So Harvard kept tracking it. How long did above-average deaths keep occurring? That’s how they got a big number. And you just have to ask yourself, Is that fair? Is that reasonable? Two months afterwards, can you really seriously call it a disaster death? Well, in my opinion, yes. If you can say this death would not have happened were it not for the hurricane … even if it’s weeks or months later, I think it’s completely fair.

After Katrina, there was a lot of infant mortality. Poor women in Mississippi—who probably didn’t get very good health care anyway—when they were pregnant [during and after the storm] got no health care. So infant mortality rose for a while, and the reason was not [physically related to the hurricane itself]. It’s because people can’t get access to health care. It just goes on and on.

Here in New York, after Hurricane Sandy, one of the veterans’ hospitals had to close. People have done studies on the excess mortality associated with closing one hospital. It’s a cumulative thing. It wouldn’t have happened if it weren’t for Sandy. That’s the way to think about it.

Godfrey: So, thinking about the COVID-19 outbreak as a cumulative thing, what could increase the death count long after this pandemic is technically over?

Mutter: In Katrina, suicide rates increased in the weeks and months afterwards because unstable people were very distressed.

The indirect effect often results from confinement, such as we are asked to do now. In crowded settings, like refugee camps and the FEMA trailers that housed so many Katrina survivors, if couples are not getting on well, then that sort of confinement can cause friction, abuse, and even death.

Displacement [when people are moved for safety reasons or to receive better care] is hard on older people with medical issues who need regular doctor visits. They are separated from their normal care providers and will not necessarily remember what the medications are that they need. They get stressed and can fail just from that. And just being displaced and not knowing when return might be possible, if at all, can cause deep depression among the elderly.

Addicts separated from dealers can become suicidal and, if they are able to find the drugs they want after a long time, can overdose.

With COVID-19, people are going to have to be removed from hospitals into different care situations [because of a] lack of hospital services. Almost certainly that care will be [worse] than hospital care.

Godfrey: When is the earliest you think we could start having good estimates about the casualties of this crisis?

Mutter: As soon as the numbers start diminishing—[when] we hear that this week, the number of cases was less than the previous week, when you’re over the peak, then you might be able to get good numbers. But that’s [likely] well into the summer.

Godfrey: And even then, if you’re looking at indirect deaths …

Mutter: That’s right. You’re looking at this issue of excess deaths, all-cause mortality. How many more people will die this April than normally die in April? It takes a little while to figure it out.

Godfrey: When would we be able to stop counting?

Mutter: It will differ from country to country. But when the new cases get to be very, very small—one new one a week—then you can go back and look at what happened. But until the numbers stabilize, it’s a moving target.

Godfrey: The Harvard study about Hurricane Maria came out about a year after the hurricane. Is that the timeline we could be looking at here?

Mutter: Yep. For sure. And you can only expect the numbers to go up, as in Maria.

Godfrey: Will we ever know how many people have really died of the coronavirus? Will we ever be able to confidently quantify it?

Mutter: There are sure to be many studies about this pandemic. Some will be accurate, some will be partisan, and the average reader will have a difficult time distinguishing. The CDC will certainly do follow-up studies to try to get numbers as right as possible.

We’ll be able to say [for example] that maybe it’s 2 million, plus or minus 100,000. You won’t get an exact number. You almost never do.